Missouri's social media case had its day in the U.S. Supreme Court — and later on X

The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments Monday in a case that could determine the level of communication that the federal government can have with social media platforms.

Murthy v. Missouri, originally filed as Missouri v. Biden in 2022, was brought by former Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt, who is now a U.S. Senator, and former Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, who now serves as the state’s governor, as well as five individual plaintiffs

Current Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey and Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill have taken up the case, which alleges that the federal government worked with social media sites to censor posts, especially those with conservative content, infringing on the First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

Bailey has previously called this “the most important First Amendment suit in this nation's history.” He contends that statements made by the federal government to social media sites could be seen as threatening punitive action if certain posts were not removed.

Attorneys from both states’ legal teams argued their case in the Monroe Division of the United States Western District Court of Louisiana in July.

That court ruled that the government had “blatantly ignored the First Amendment’s right to free speech” when it suggested that select posts be removed from social media platforms.

Among the posts in question were those that questioned the origin of the COVID-19 virus, the results of the 2020 election, information casting doubt on the efficacy of vaccine and mask mandates and posts theorizing about the Hunter Biden laptop controversy.

In its 155-page decision, the lower court alleged that federal officials “almost exclusively targeted conservative speech,” granting an injunction that barred any federal officials from communicating with social media companies about removing content.

In September, a three-judge panel of the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans agreed with the lower court’s overall opinion, but vacated a large portion of the injunction against federal officials.

Much of the lower court’s injunction was deemed “vague and broader than necessary,” so the 5th circuit judges only left in effect a clause that prohibited alleged coercion by federal officials seeking the removal of certain content on social media.

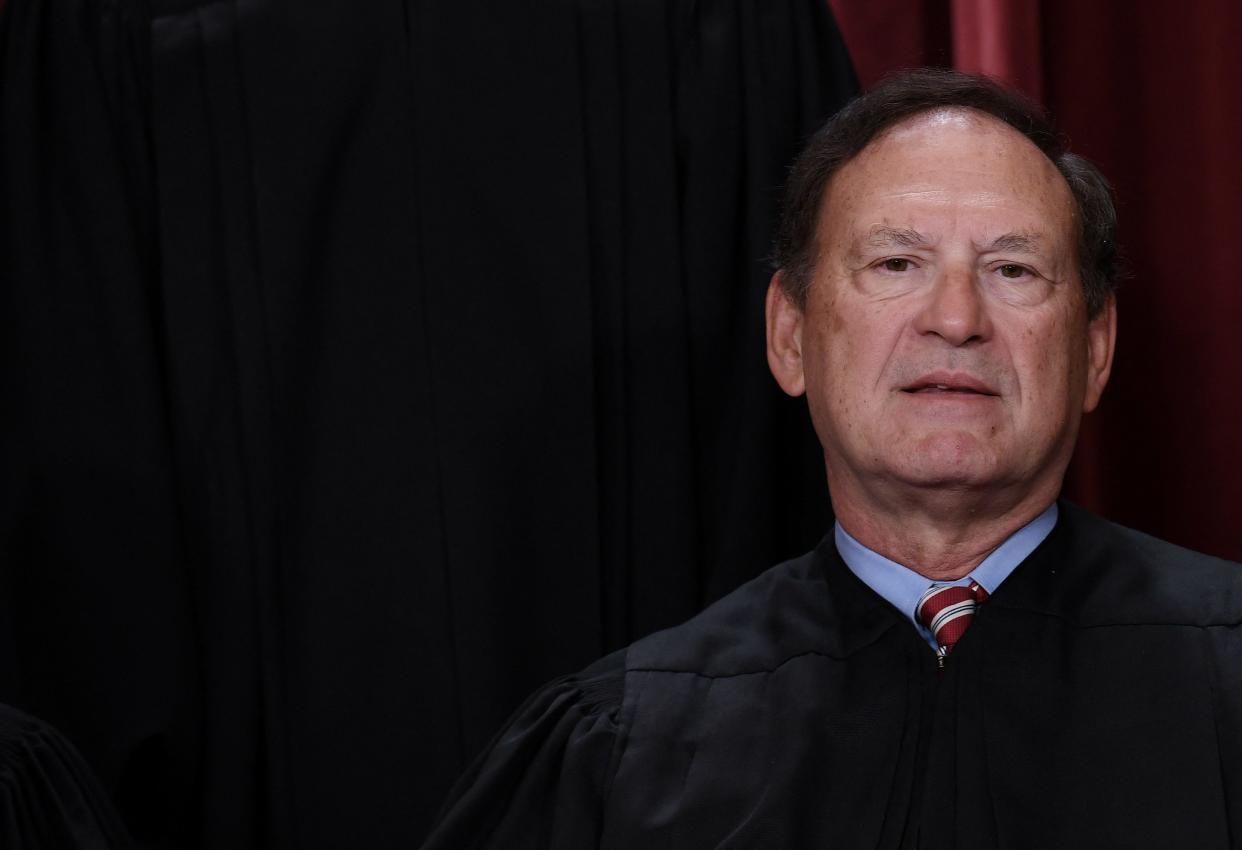

In late October, an injunction was granted by the nation’s highest court that stopped the 5th Circuit’s prohibition from remaining in effect, although U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito penned a scathing dissent to the decision, joined by Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas.

More: U.S. Supreme Court will hear Missouri case challenging federal influence on social media

On Monday, Supreme Court justices greeted the arguments made by Benjamin Aguiñaga, the solicitor general for the Louisiana attorney general, with some skepticism and concern. Among the issues discussed by the justices is the fact that prohibiting communication between social media and the federal government could have unforeseen consequences.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett presented the situation of the FBI needing to contact social media sites when doxxing has occurred, meaning someone’s personal information was released publicly in order to cause them harm. In these cases, the FBI would need to request removal of the post by the social media sites.

Aguiñaga, who characterized himself as a free speech purist, said that the FBI should only be allowed to do so if the speech is not protected by the First Amendment, but countered Barrett’s argument by saying that wasn’t what was happening in this case.

“Well that’s just falling back on, ‘Well, this case is different. This case is different, and so a different legal standard should apply.’ But you know, what we say in this case matters for other cases, too,” Barrett said.

Justice Elena Kagan asked Aguiñaga to produce his best piece of evidence showing that “the government was responsible for one of your clients having material taken down.”

He referred to the removal of posts by one of the plaintiffs, Jill Hines of Louisiana, whose posts regarding COVID-19 were removed in July 2021, two months after the Biden Administration emailed social media platforms about moderating posts containing pandemic misinformation. Kagan seemed unconvinced by this example.

“So that decision two months later could have been caused by the government’s email or that government email might have been long since forgotten because there are a thousand other communications that platform employees have had with each other, a thousand other things that platform employees have read in the newspaper,” Kagan said.

Justice Samuel Alito, who dissented from the majority justices in issuing the October injunction, seemed the most open to the argument from Aguiñaga. He referred to the federal government “pestering” social media sites, then asking to work together as partners, editing any posts for accuracy before they were published.

“I cannot imagine federal officials taking that approach to the print media,” Alito said.

Although Aguiñaga and Alito both took issue with some of the profane language in the exchanges between the government and social media sites, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who previously worked in the White House, said he knows of “experienced government press people throughout the federal government who regularly call up the media and berate them.”

Kavanaugh’s comments were seconded by Kagan, who said,“This happens literally thousands of times a day in the federal government.”

Speaking on behalf of the U.S. Justice Department was Brian Fletcher, principal deputy solicitor general, who argued that the speech used as evidence did not constitute coercion, and social media companies routinely declined some of the requests made of them to remove content.

“They didn’t hesitate to do it, and when they said ‘no’ to the government, the government never engaged in any sort of retaliation,” Fletcher said. “Instead, it engaged in more speech. Ultimately, the president and the press secretary and the surgeon general took to the bully pulpit. We just don’t think that’s coercion.”

Aguiñaga disagreed, countering by saying that “pressuring platforms in back rooms shielded from public view is not using the bully pulpit at all. That's just being a bully.”

Following the nearly two-hour oral argument, Attorney General Bailey issued a statement again touting the importance of this case in terms of defending the First Amendment.

“My office brought this lawsuit to halt the disgusting silencing of millions of Americans by the Biden Administration,” Bailey said. “We feel confident after today’s arguments, and look forward to reminding the nation that the First Amendment still means something in this country.”

Later Monday evening, Bailey joined Elon Musk in a live discussion on X, formerly known as Twitter, which Musk purchased nearly two years ago. Bailey emphasized the importance of this case, saying, “I think this is one of the most important strategic objectives in securing the soul of our nation.”

“I think that the bedrock of democracy is freedom of speech,” Musk said. “Because if you can't say what you want to say then I think that's essentially political coercion.”

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: U.S. Supreme Court hears MO case involving social media censorship