Miami’s political godfather Joe Carollo, unfazed by $63M beating, can’t wait for next fight

During a festive Friday night at Domino Park Plaza in Little Havana, on a stage decorated with red and gold balloons, singer Diveana — the Madonna of merengue — performed a bouncy encore with her band, swinging her hips and blowing kisses to the crowd. Joe Carollo danced beside her.

Carollo, not a graceful man in movement or manner, looked even more ungainly in his baggy gray pants and monogrammed city of Miami windbreaker next to a smooth, sexy professional in latex leggings.

But Carollo didn’t care. His skin is tempered like a boxer’s.

His distinctive monotone, used to harangue and belittle those who challenge him, lifted into song. His lips, typically clamped in a rigid line, curled into a smile.

Imagine that. Commissioner Joe Carollo, for a long time the most powerful politician in Miami, aka “Crazy Joe,” happy.

His footwork was heavy but playful. When he wore orthopedic boots as a kid, and got mad at his cousins, he kicked their shins until they were black and blue.

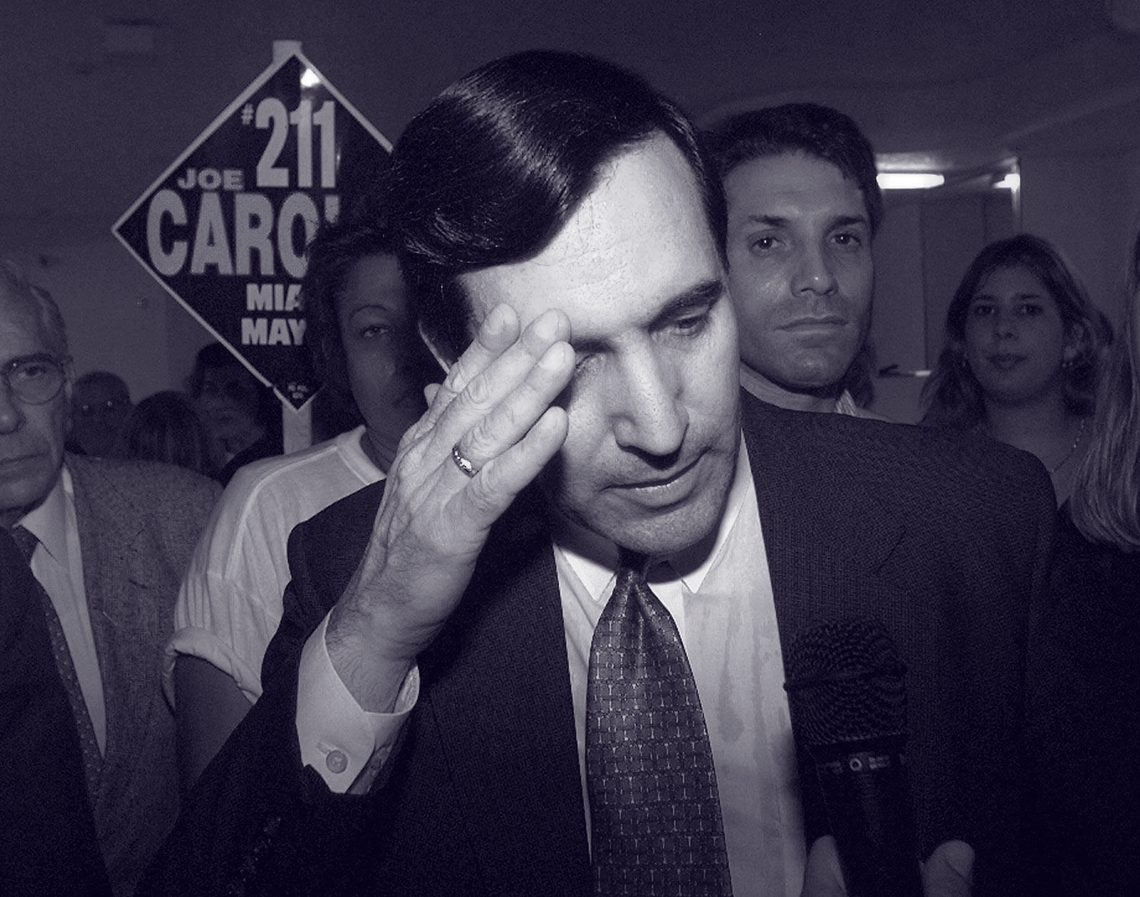

Looking down on his realm — a city infested by corruption scandals multiplying like mold spores — Carollo embraced the applause. Socked with a $63.5 million judgment in June and portrayed in November’s election as a cockroach to be squashed, Carollo was undismayed.

“See? Am I the monster depicted by my enemies?” he asked.

It is rare to find Carollo in a state of joy. Conflict is his cafecito. Bad blood nourishes him.

“He thrives on turmoil,” said the second of Carollo’s three ex-wives, Mari Ledon. Carollo was charged with simple battery and spent a night in jail as mayor when he threw a tea container that hit her in the head in 2001. “His passion is destroying people.”

Now in his fourth decade as godfather of Miami’s serial political drama, Carollo, 68, is destroying the city, too, say his critics, whom he calls “haters.”

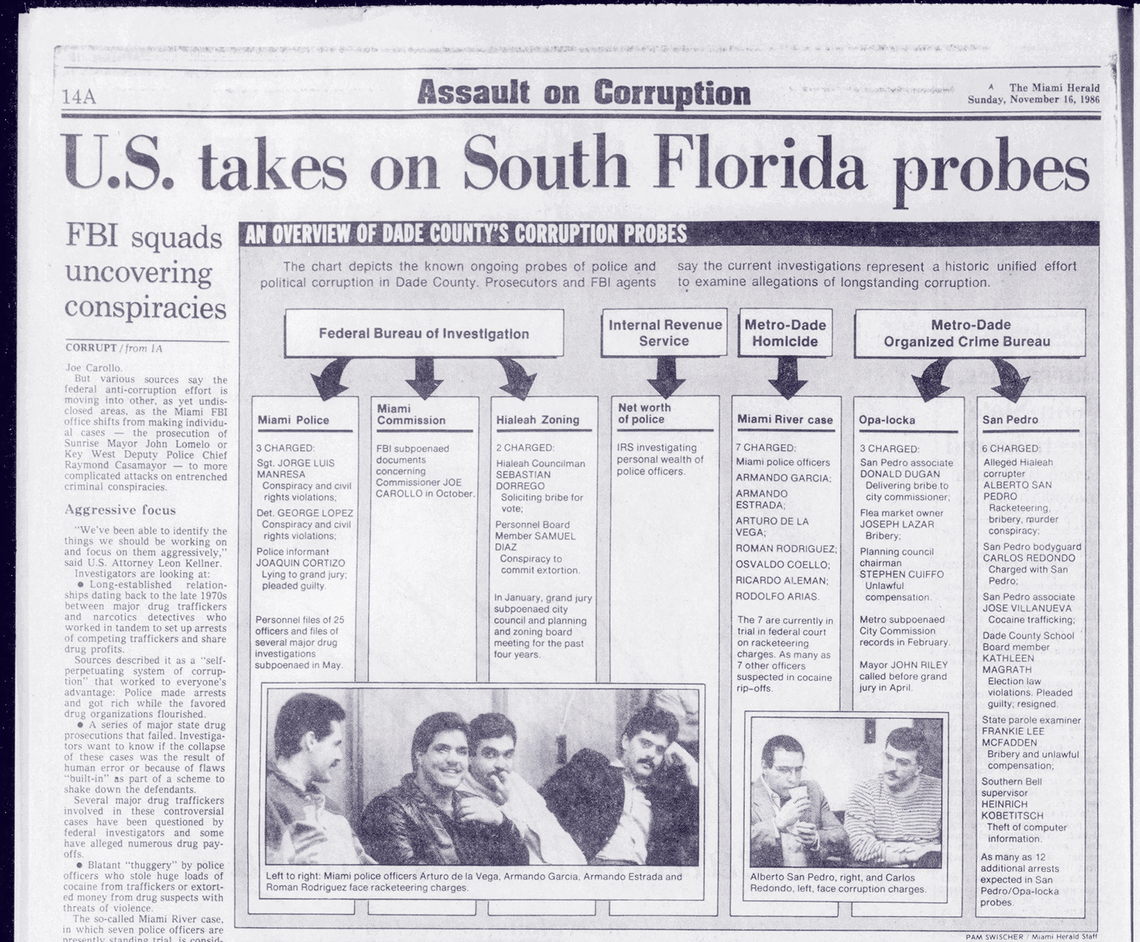

At the end of a stormy year even by Miami standards, Miami is in crisis. Mayor Francis Suarez is under FBI investigation for allegedly accepting payments from a developer who needed help with a stalled project in Coconut Grove. Ex-Commissioner Alex Díaz de la Portilla was arrested and charged with taking bribes. City Attorney Victoria Méndez and her husband are accused in a civil lawsuit of exploiting an elderly man in a house-flipping scheme.

Most ominous, the city faces two lawsuits similar to the one Carollo lost in the most resounding defeat of his career. The two Little Havana businessmen who sued Carollo claim two dozen city officials followed Carollo’s orders in a vendetta to ruin them. They’re seeking $85 million in damages. The city has paid $2 million in attorneys’ fees for Carollo, who plans to appeal.

Eight weeks of testimony at Carollo’s trial showed how he rules the city by wielding fear of retribution like a machete. You cross Carollo, he crosses you out.

He is, once again, directing the show at City Hall. Suarez has been an absentee mayor, out of town for weeks at a time, running a longshot presidential campaign that flopped and recruiting clients in the Middle East for his law firm. Díaz de la Portilla, Carollo’s former ally, charged with accepting $245,000 in bribes, lost November’s election to Miguel Gabela, who vows to clean up city government. Gabela’s first resolution at his first commission meeting was to fire Méndez. It was deferred.

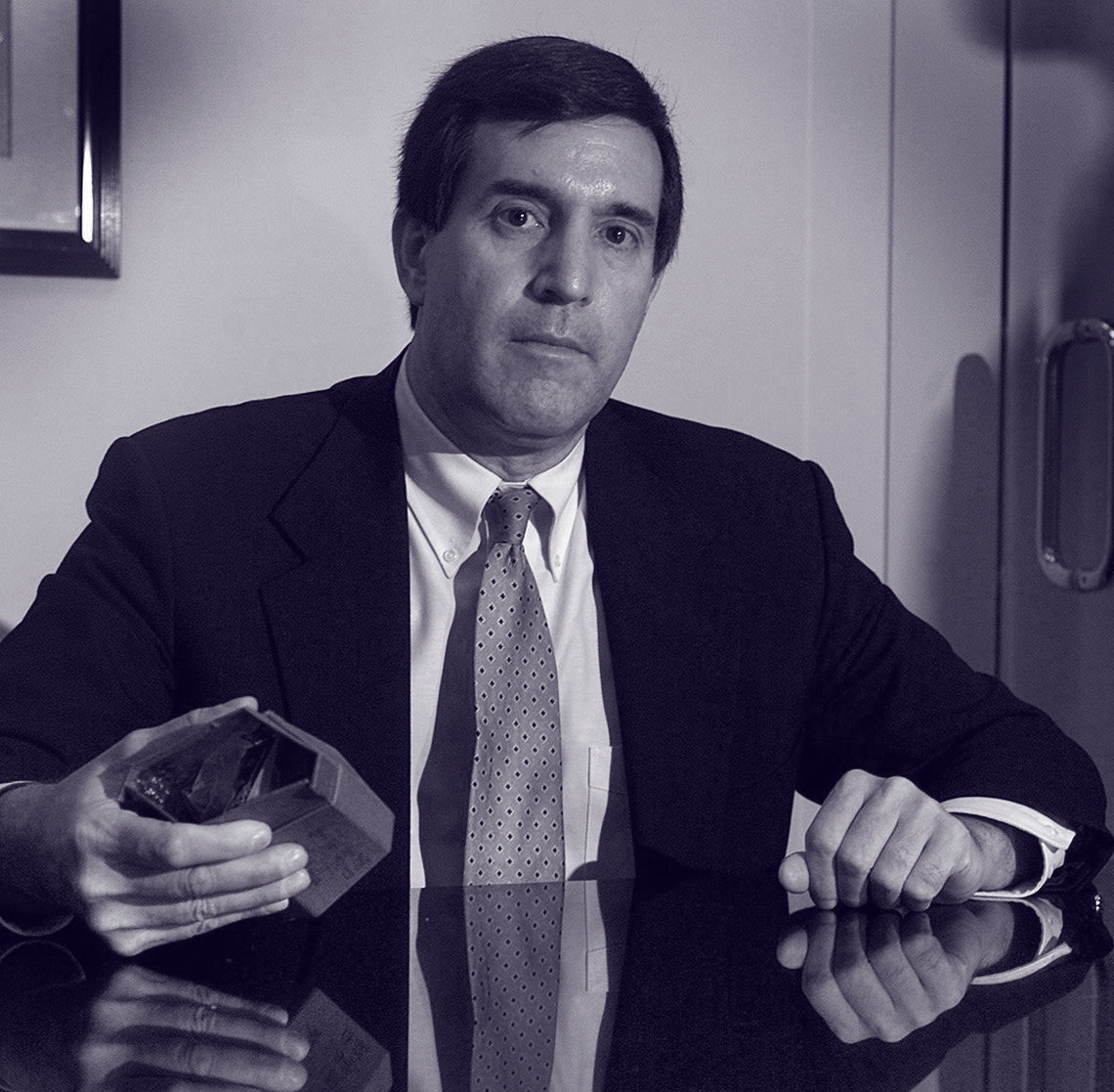

Carollo has survived because he’s never been charged with using his office to get rich. He’s greedy for power, not money, his accusers say.

“The people who call me a bully are the true bullies, laughing in the face of residents, trying to get away with illegal things until I caught them,” Carollo said. “Their problem is they can’t buy me.”

Business owners Bill Fuller and Martin Pinilla beat Carollo in federal court by proving he deployed city officials from the building, legal, code enforcement, fire and police departments in a harassment campaign to shut down their popular Ball & Chain club, and unplug the green neon sign that’s been a beacon of Little Havana’s renaissance.

Carollo has also turned Miami’s signature downtown bayfront park into a battlefield, calling its neighbors “old farts and rich elitists” as he fills it with kitschy animal statues, exercise equipment and, in his next riposte, six pickleball courts on its emerald lawn.

Even Carollo would admit he’s reviled, yet he endures. He knows he has all the love — and votes — he needs from the loyal abuelas of his power base. He understands them because he, too, is an exile, uprooted from his hometown of Caibarién, Cuba, and sent to Miami on an Operation Pedro Pan flight in 1961.

“He delivers for us, we deliver for him,” said Maria Campos, 86, who emigrated from Cuba in 1971. She is tenant leader at a housing complex for the elderly where Carollo will be handing out thousands of lechon dinners for Christmas.

The two-time mayor may run again in 2025. But his most valuable foil, Fidel Castro, is dead, replaced by a new wave of unintimidated citizens determined to oust him as a barrier to the city’s maturation.

Two rookie commissioners elected in a mini revolt could upset the balance of power on the five-member commission, where the magic number of votes needed for ruling the Magic City is three. Carollo has already engaged in a shouting match on the dais with Gabela, who refused to back down. And, the recently redrawn district map, denounced by voters, could be rejected; it’s the subject of a racial gerrymandering lawsuit. The new district lines enabled Carollo to move back into his North Coconut Grove home, and by residing there he can protect it from confiscation by Fuller and Pinilla in their attempts to collect damages.

“Joe Carollo is a broken man who has broken our city and almost every single relationship in his life,” said Fernand Amandi, a pollster and lifelong Miamian. “Taxpayers are an afterthought who have paid the price. Miami exists as a cartel, only to enrich or entrench the power of its leaders.”

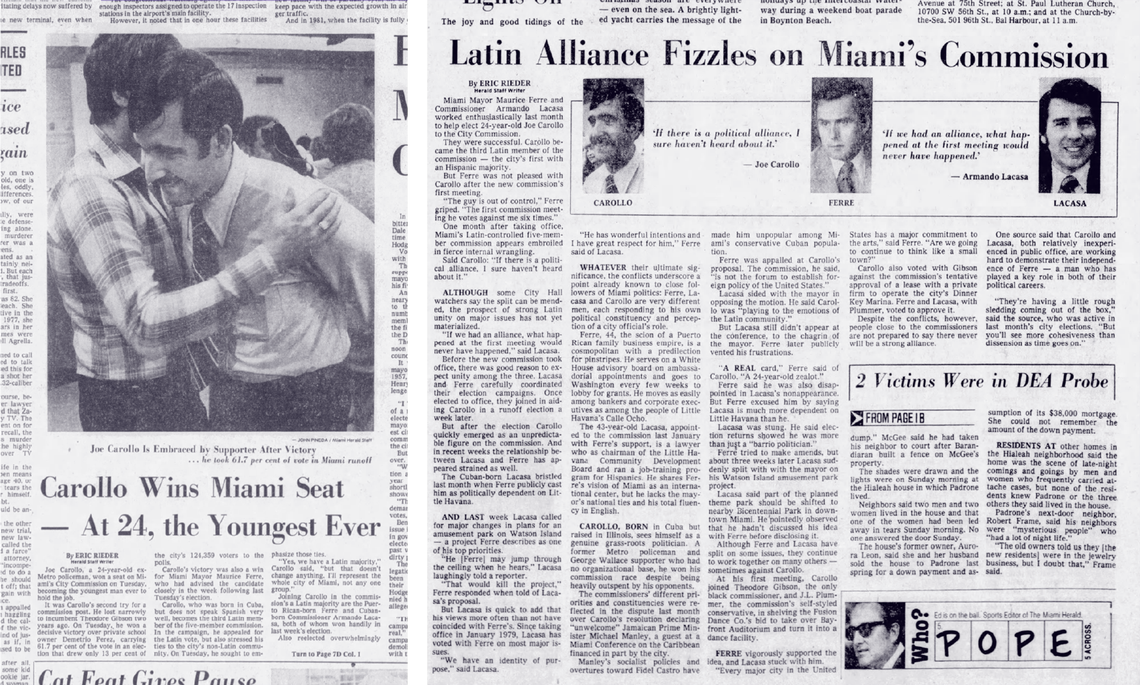

It is a time of reckoning for Carollo and Miami. Seas are rising. Neighborhoods, including Little Havana, flood during routine rainstorms. Brutal heat, traffic, housing costs and property insurance rates are making Miami unlivable. Sounds apocalyptic. Maybe it will take an apocalypse to unseat Carollo, who first won in 1979.

“Joe is on his ninth life,” said Miami filmmaker and fierce Carollo critic Billy Corben. “The Carollo cycle will not repeat.”

Carollo relishes such obituaries. What really made him grin as he stood in the epicenter of his district was the sight of Domino Park Plaza’s 25-foot Christmas tree, rising above the Little Havana festival he commandeered from Fuller, and the steeple-like marquee of the Tower Theater he seized from the “film snobs” who ran it — pointing like two giant, illuminated middle fingers at the Ball & Chain club directly across Eighth Street.

“No matter what my opponents think or say or do, what frustrates them is that I’m always the last man standing,” he said.

Breathing fire

Angry, vengeful, paranoid, a remorseless bully: These are trademark Carollo traits, according to city employees, two of his daughters, citizens who have argued with him and former allies double-crossed by him.

He was challenged to a duel by the late Jorge Mas Canosa. He betrayed Mayor Maurice Ferre on live TV. He referred to Miami’s first Black city manager as an “Oreo cookie” and joked that Commissioner Ken Russell’s haircut looked like North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s haircut; Russell is Japanese American. A receptionist testified he coerced her into falsely accusing two aides of sexual harassment. He humiliated ex-Police Chief Art Acevedo at a seven-hour public meeting by showing an old video of Acevedo doing an Elvis Presley impersonation at a Texas fundraiser, zooming in on Acevedo’s crotch and declaring that such gyrating in a tight white jumpsuit was grounds for firing.

Acevedo, who had the gall — or guts, depending on your side of things — to say Miami government is a criminal enterprise run by the “Miami mafia” is suing for wrongful termination. Moments after Carollo engineered the vote to fire Acevedo, he played the theme from the Godfather movies on his cellphone. “Miami Mafia” was coined by Castro to malign exiles. Carollo delighted in it as proof he was a thorn in Castro’s side, and hung a picture in his office of his face photo-shopped over Marlon Brando’s face on “The Godfather” poster.

Asked if he has any regrets about his tempestuous career — a tirade he could take back, a firing he could undo, an obsession that went too far — Carollo is defiant.

“I do not regret not being a coward,” he said. “When people awaken the dragon in me, I breathe fire.”

Carollo’s current arch rival is Fuller, co-owner of Ball & Chain and a dozen other Little Havana properties in the heart of Carollo’s District 3. During his feud with Fuller, Carollo took over the 20-year-old Viernes Culturales festival, deriding it as a “flea market,” and made it his own, renaming it Viernes Pequeña Havana. Lest you forget, Carollo put his picture on signs promoting the Friday night party. Fuller wept on the witness stand when he described Carollo’s efforts to wipe him out.

Carollo and the city bombarded Fuller with code violation citations, according to the lawsuit. City officials showed up at all hours, assailing Fuller’s properties 185 times, even raiding his 2017 office Christmas party. Permits were denied, closing businesses or halting renovation projects. Demolition orders were issued. It was suffocation by red tape, Fuller said, mentioning the night Carollo spied on valet parkers in a church lot and when confronted said he was there to consult with the priest. At 12:15 a.m.

Fuller says Carollo’s attack has cost him more than $28 million.

Carollo says Fuller and Pinilla are “crooks” who evaded building and safety regulations, disrupted residents’ daily lives with loud music and construction chaos, and cheated the city out of thousands of dollars in fees. He claimed, without proof, they were partially funded by Venezuelan investors, enchufados who were cronies of socialist strongman Hugo Chávez and successor Nicolás Maduro. Carollo made similar accusations when he turned on the Doral city officials who hired him as city manager in 2013.

“I’ve been committed to the revival of Little Havana for 20 years. I’m not some gringo outsider criminal,” Fuller said, telling how his grandfather owned a lumber mill in Cuba, his mother is Cuban and his uncle was executed by a Castro firing squad. “It’s worse than a shame, it’s pathological that instead of collaborating with us, Joe set out to destroy us and the diamonds of his own district.”

Carollo also took over the historic Tower Theater from Miami Dade College, declaring that the art cinema and home of the Miami Film Festival only served an audience of “10 to 15 elitists.” He offered the building to the Bay of Pigs Brigade 2506 veterans for a museum. They didn’t want it. So Carollo has implemented new programming that he believes will sell more tickets: Celia Cruz Forever, an exhibit featuring all things “Azucar!” and Cuban-American comedy acts.

It’s part of his effort to prevent the “de-Latinization” of Little Havana, a concern he expressed to former City Manager Emilio González when they were walking down Calle Ocho and Carollo told him to remove a mural that had “too many Black people,” González testified.

When Carollo walked by the mural last Sunday, he said he has no problem with it or Black people, that Gonzalez and others who testified against him are “liars spewing lies to smear and defame me — it’s a cheap shot to call me racist.” Later, he stopped at Jackson Soul Food in Overtown for his favorite meal, fried catfish, complimented the cook, chatted with a young Black woman, gave her his phone number and encouraged her to call so he could get her a job on his staff.

It’s easy to lampoon Carollo. Put a big top over City Hall. Sell tickets to the theater of the absurd in chambers. Call it a banana republic run by dictator wannabes. In fact, during the Elián González tug-of-war in 2000, when Carollo was mayor and appearing nightly on Geraldo Rivera’s program and Radio Mambí, protesters brought crates of bananas to City Hall. Carollo’s retort: “We don’t grow bananas commercially in Miami; we import them. “

Spanish-language-radio host and former mayor and commissioner Tomás Regalado says Carollo has damaged local democracy.

“The worst consequence is voter apathy,” Regalado said, citing 12% turnout in last month’s election. “The people of Miami are so fatigued they have given up on Miami.”

Cynical citizens don’t vote or run for office because nothing ever changes, ensuring that nothing will change, he said.

“I think Carollo has made Miami worse by holding it back,” said David Winker, a lawyer known for representing citizens in grass roots vs. Goliath cases. Winker was involved in an unsuccessful 2020 effort to recall Carollo. During COVID, Winker worked from his Shenandoah house and the city fined him for practicing law from home without a business tax license.

Plenty of cities have dirty histories. But Miami’s political culture is different, Winker says. Not only does Miami not operate according to principles taught in civics class, but nobody tries to hide it.

“It’s not a government for the people. It’s a government for the commissioners to get whatever they want,” he said.

Carollo counters that he has raised half a billion dollars in revenue since 1999. That’s why the city should pay his legal fees or any damage awards against him, he says.

“No elected official has come close to what I’ve done,” he said. “If anyone has paid his way, it’s me.”

Carollo’s personal ventures haven’t always been profitable. Two restaurants failed, including Shogun Joe’s, an Asian fusion spot. He also owned Genesis Security, a stone crab importing company and a medical supply firm. Carollo has worked as a political consultant, earns a $58,000 city salary and estimates his net worth at $2,345,023.

Carollo’s colleagues count on him to be a tough negotiator, he said, driving by the Cuba Under the Stars show he brought to Bayfront Park (his picture is on promotional signs). He cited how he increased the Ultra music festival’s contract from $600,000 to $2 million. He says he didn’t allow the city to get fleeced on the Freedom Park mall and soccer stadium deal the way his predecessors got fleeced on the Marlins ballpark that will cost taxpayers $3 billion.

“I know a lot of people, I know numbers, I know the rules,” he said. “When I was at Doral, I out-negotiated Donald Trump. He didn’t have permits for a pedestrian bridge. We stopped it cold. Trump tried to call me for 30 days. He said, ‘Joe, I could have gotten ahold of Obama quicker than you.’ I said, ‘Donald, you have to get a permit.’ He got one.”

Exiled and estranged

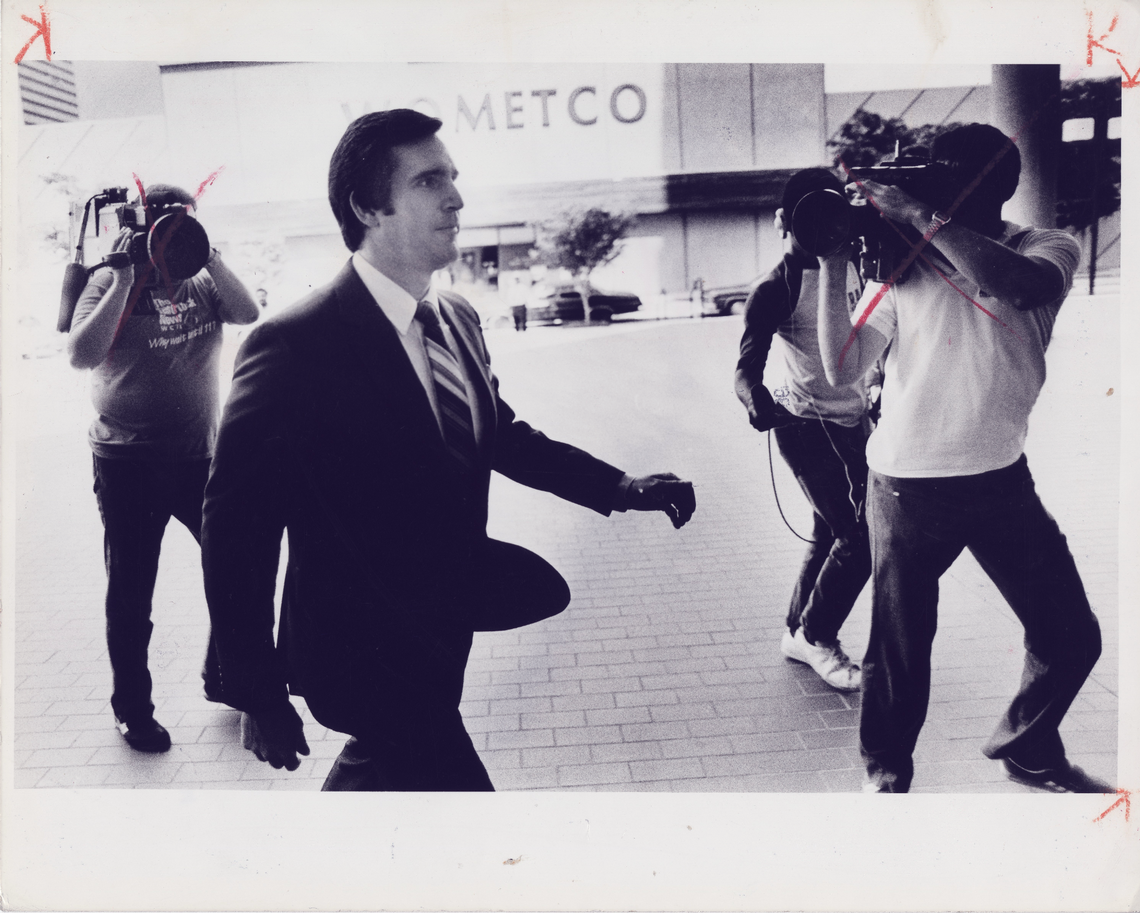

Carollo has been in and out of office for so long it’s hard to remember Miami without him.

He first arrived from Cuba as a 6-year-old boy, frightened and alone. His Rosebud: A bag of toy soldiers he clutched on the plane. Somewhere along the way, as he was moved from shelter to foster care, he lost the soldiers. He was separated from his parents for six months.

“It was traumatic to feel abandoned, to not know when you’d see your mom and dad again,” said Carollo. He believes his exile experience as a child enabled him to connect with Elián González, who was 6 when fishermen found him adrift on an inner tube off the coast of Fort Lauderdale and brought him to shore. His mother had disappeared during the journey from Cuba. “Six months felt like six years.”

Carollo grew up on Chicago’s North Side. He attended St. Jerome’s, where he met Mayor Richard Daley, “a major influence on me and my aspirations.” He was an altar boy and captain of the crossing guard. He remembers Sister Delphine playing Notre Dame fight songs on her piano. She slapped every kid in the class except him.

The family moved to Miami and Carollo played running back and linebacker at Miami High.

He graduated at 17, earned a degree at Miami Dade College, joined the county police force at 18 and worked as a public service aide. He was reprimanded for placing a cartoon satirizing the Ku Klux Klan in Black officers’ lockers and warned to “subdue his high degree of natural aggression.”

Carollo was a security guard when he first ran for commissioner in 1977. He lost to the Rev. Theodore Gibson, a civil rights activist, then two years later at age 24 defeated Demetrio Perez to become the city’s youngest commissioner ever. At his very first meeting, Carollo was described by Ferre as “out of control.”

“When we met, I thought he had a bright political future. We were both idealists, coming from communist Cuba,” said ex-wife Mari Ledon. “Then he, well, he deteriorated.”

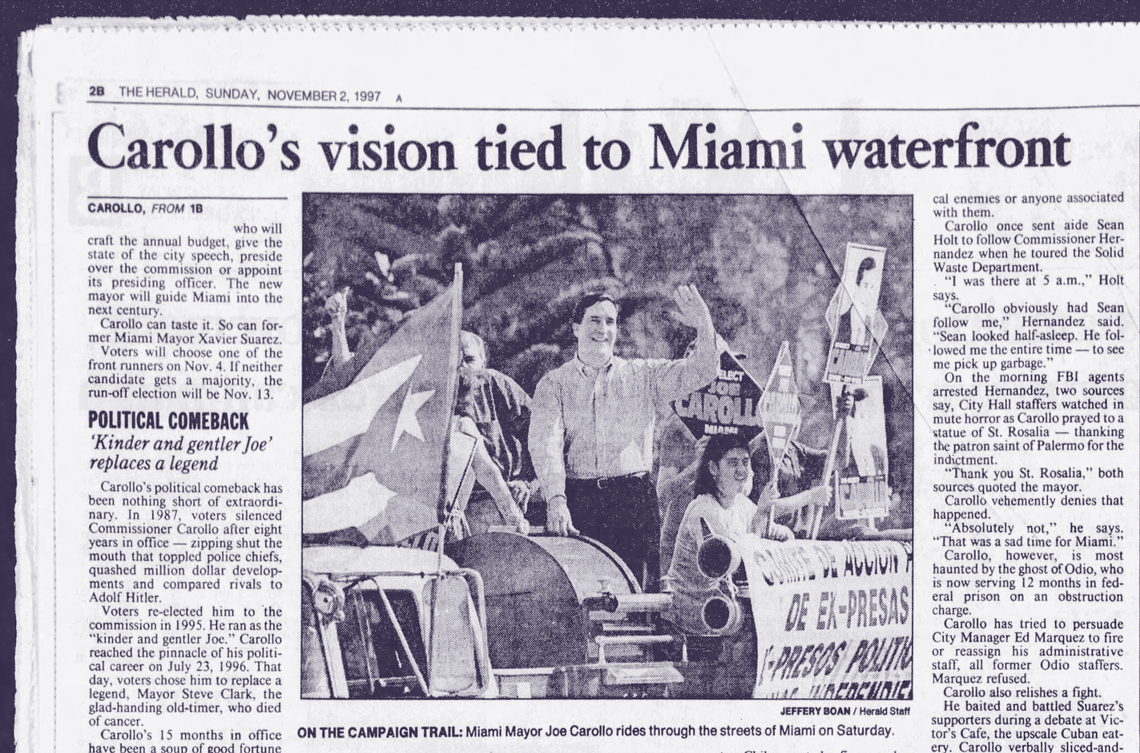

Carollo served as mayor twice, the first time in 1996 after Steve Clark died, and again in 1998 after losing to Xavier Suarez, father of the current mayor, and suing to overturn a fraud-marred election. Absentee ballots were falsified, and a man named Manuel Yip, who had been dead for four years, cast a vote.

“People forget my role in correcting injustices,” Carollo said.

Carollo prefers to keep his personal life private. He has a son and daughter by his first wife, and six grandchildren — nine including his wife Marjorie’s grandchildren. His third marriage lasted 83 days. He adores Marjorie.

His second marriage was to Mari Ledon. Their daughters were painfully direct when they spoke about their severed relationships with Carollo.

Caroline Carollo, 34, a Miami attorney, has had no contact with her father since 2008. Her sister Kelley, 32, hasn’t seen or talked to him since 2003.

“We used to get a birthday phone call, two days late, but that stopped,” said Kelley, an interior designer in New York City. “I was emotionally attuned as a child, I’m told, and I remember I used to cry when he held me. He was not likable and I just sensed it.”

Her memories: “Him yelling, throwing tantrums, being unpleasant,” she said. Asked if there’s another side of Carollo beyond his cantankerous public image, Kelley paused.

“No,” she said. “He’s a controlling, chauvinistic man who has to dominate and make others suffer.

“What have I learned from my father? To seek the exact opposite of him in a partner.”

Caroline said the most important lesson she’s learned from him is, “It is better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt.”

Carollo said Ledon “poisoned” his daughters against him during a bitter divorce.

“The scars I have, the nights I’ve cried,” he said.

Ball & Chain

On a recent tour of his district with a reporter, Carollo wove adeptly through its neighborhoods, greeting constituents, pointing out parks he’s created or improved, lots where he wants to build affordable housing and a street where he came to the rescue of residents frustrated by the county’s refusal to close it to dangerous cut-through traffic. Carollo put up barricades, assigned police patrols and won two years of peace until the county forced him to go away.

Along the Miami River, Carollo showed off Jose Martí Park, a magnet for families in one of the poorest sections of his district. He stopped to talk with a man pushing his daughters in a stroller who is worried about speeding cars. Carollo shared his phone number and assured him they’ll solve the problem.

On Flagler Street, Carollo pointed out where homeless people congregate. He talked with a group of men lying on the sidewalk on a recent night at 1 a.m.

In a city meeting earlier that day, Carollo had challenged a staffer’s assessment that the city was doing a good job with the homeless and asked the employee to accompany him that night — also inviting City Manager Art Noriega so Carollo wouldn’t “be accused of giving orders or any BS.”

Carollo spoke to an elderly man in a wheelchair. “He’s Cuban and this is what the Cuban regime does — dumps its people in the retirement house of Miami. I can see he has mental problems.

“I can tell this gentleman is high on drugs,” Carollo said of a man singing “Row, row, row your boat.” “I feel bad. But you’ve got to find a balance between being humane and your obligation to make communities safe.”

Carollo gestured toward the Leonesa Fritanga diner, recalling how friendly the neighborhood used to be “when you had old folks ordering steak sandwiches and mamey milkshakes, telling stories.”

“Miami will become a city strictly for the rich and famous. It’s already a Casablanca of embezzled uber-wealth and luxury condos,” he said. “I care. I fight.”

Carollo constantly circled back to Southwest Eighth Street and the three-block section humming with people visiting cigar shops, guayabera shops, fedora shops, cafes, galleries, ventanitas. Tourists ate arroz con pollo at El Pub, “where the Cuba of yesterday lives today,” and snapped photos inside Domino Park of players slapping tiles on tables with an emphatic flourish.

“It’s still Cuban but also Little Nicaragua, Little Caracas,” Carollo said.

Carollo kept pausing in front of Ball & Chain, where costumed showgirls wiggle and beckon at the front door, bands perform nonstop and patrons dance to the salsa beat. Fuller brought it back from the dead and made it a catalyst for the neighborhood.

“That’s what the prince of Little Havana would have you believe, but the people of this community who can’t sleep at night have been shackled by this ball and chain and the city has been put in financial jeopardy by the commotions Mr. Fuller has caused,” Carollo said, lips tightening. He asserts that, until he scrutinized Fuller, the city turned a blind eye as Fuller and Pinilla built what Carollo calls “the Eighth Street Boys’ empire” without permits or licenses.

“Ball & Chain did not make Little Havana. Little Havana made itself,” Carollo said.

In his Futurama building office, Fuller told a different story. Since the 2017 commission race, when he supported Carollo’s opponent, Fuller said he’s been hounded by Carollo and “the arsenal of city employees and resources he mobilized.” When Carollo won, Fuller sent an olive branch text, saying “let’s work together” and an invitation to Fuller’s holiday party. A uniformed code enforcement officer crashed the party and “laid it out for me: Prepare for retaliation by Joe Carollo.”

Fuller and Carollo met for the first time six years ago for breakfast to discuss the future of Little Havana. Fuller’s goal is to keep the area true to its history and keep the chains — like the Starbuck’s down the street — out.

“Joe’s opening lines to me were, ‘You know my brother Frank. He was a mistake. He was born much later than me,’” Fuller said, referring to former commissioner Frank Carollo. “I’m wondering, what kind of malicious guy says that? Then he tells me his vision for Calle Ocho is aluminum palm trees with LED lights.”

Fuller says he had no desire to sue Carollo or the city but felt he had no choice if he was to stay in business. He and Pinilla began documenting the threats, inspections, revoked permits, surveillance, City Manager Noriega rolling out a measuring tape in front of Fuller’s Mexican taqueria, Assistant City Attorney Rachel Dooley interrupting a meeting to stop a vote on historic designation for five of Fuller’s properties, Carollo skulking around in the dark, hiding behind trees, announcing “I am the law!”

Carollo sees himself as an investigator pursuing truth. On the facts, he’s usually right. He remembers names, dates, addresses, branches of family trees, numerals to the exact decimal. He can decipher campaign finance reports, recite budget figures, pick apart tax returns, deconstruct code regulations, list liquor licenses, do the math on occupancy limits, recall dialogue to the word and measurements to the inch. Carollo argues he was able to present only a fraction of his evidence in an unfair trial.

Given the filing cabinet in his head, it’s no wonder the plots of his conspiracy theories are fantastic. Carollo’s ex-wife Ledon and their two daughters said he used to keep the curtains of their house closed and checked for hidden bugs. He had a remote starter for his car. He had them tailed by private detectives during post-divorce legal fights over money.

Carollo does not go down rabbit holes so much as he descends into labyrinthine tunnels that run for miles. To follow him is exhausting.

“I’ll make a deal. If Mr. Fuller can prove the $6.5 million of federal PPP relief they got was spent appropriately and their employees were paid, I’ll resign,” Carollo said, pivoting to his often-repeated but never substantiated insinuation that Fuller committed mortgage and voter fraud.

“He’s got two new lapdogs on the commission but there are questions about the origins of their campaign funds.”

“Hates nature ... loves concrete”

Carollo seemed tense and excited as he turned into Ferré Park, 18 acres of grass and trees bathed by Biscayne Bay breezes, reclaimed from its crime-ridden Bicentennial Park years as a derelict Indy Car racetrack. It was designed at a cost of $10 million to be Miami’s downtown garden.

Carollo sees it as an expansive ring, surrounded by ropes, with himself in one corner, spitting onto his palms, and the park’s Biscayne Boulevard neighbors in the other. “Bring your popcorn,” he says of the ongoing fight for dominion.

They want him replaced as chair of the Bayfront Park Management Trust, a little-known board that oversees Ferré and Bayfront parks. Neighbors accuse him of running it like his personal estate. He counters that they treat it like their private front yard.

“The trust is a treasure where Joe can exercise his power,” Regalado said.

Contrary to the master plan, which Carollo disdainfully calls “the bible,” he’s added features that neighbors say nobody wants — such as an outdoor gym and a promenade to Miami’s premier art museum lined by 57 colorfully painted statues of dogs and cats. Two 300-square-foot LED billboards will be built. A dog park covered with artificial turf is way too large, even dog owners say. Carollo’s got more ideas — soccer fields, pickleball courts, beaches festooned with University of Miami and FIU logos.

“I told him, ‘Joe, you won’t be satisfied until you turn this into Coney Island,” Michael Feuling said from his 26th floor condo overlooking the park. He estimates 20% of the park’s green space has disappeared in the past two years. “He does everything according to his whims, without public input or professional advice. It looks like landscaping by Home Depot.”

Claudia Roussel helped launch a petition drive to have Carollo removed from the chairmanship. Neighbors discovered he was doing work without permits, including the removal of a large ficus tree. The resulting outcry helped new District 2 Commissioner Damian Pardo attract votes with his anti-Carollo platform.

“Carollo hates nature and loves concrete,” Roussel said.

Carollo strode to the gym that sits under banyan trees. The planning board ruled Carollo used loopholes to install the exercise equipment without proper notice and it must be removed.

“Here we have the mortal sin,” he said. “These rich condo dwellers say they have gyms in their buildings and want passive green space. What is that, a place where you sit around waiting to die?”

Carollo approached a woman walking her two dogs and asked if the gym should be ripped out.

“Yes,” she said. “It’s an eyesore. It’s more clutter.”

He asked four Frisbee players if they liked the gym and they said sure, they might use it.

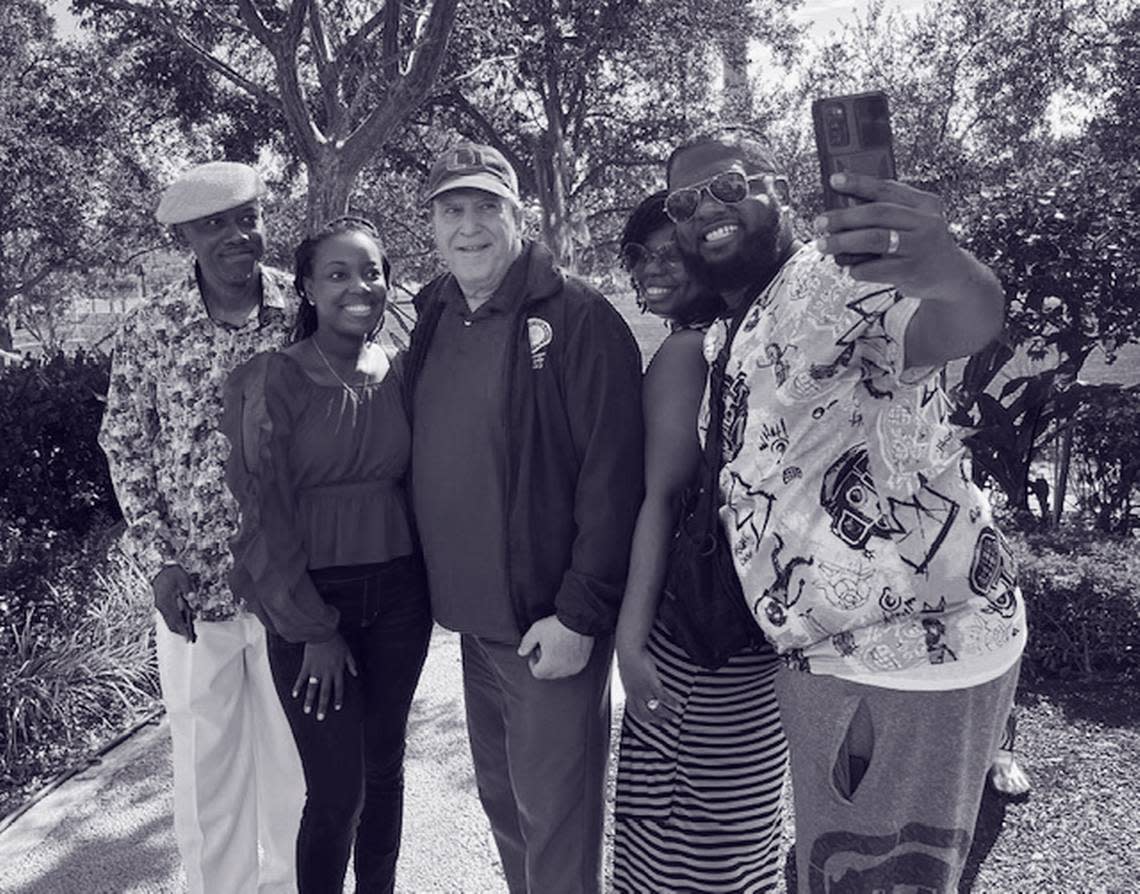

At the Dogs and Cats Walkway, Carollo asked visitors from Norway and North Carolina their opinion of the supersized poodles, chihuahuas and bulldogs. Critics call it hideously tacky.

“Are you the artist?” asked a woman from Colorado, snapping photos of the metal menagerie.

“I’m the commissioner who put this in,” Carollo said. She and her friends took a selfie with him.

The project, which Carollo says has attracted 350,000 visitors in one year, was installed at a cost of $1 million with a no-bid contract.

“My enemies insinuate I got a kickback,” Carollo said. ”I’ve never lined my pockets doing city business.”

Carollo pointed to bronze sculptures he acquired on loan, picked up a piece of trash and noticed that newly planted impatiens were wilting. He called a supervisor to get them watered.

“Looking more like a world-class European park every day,” Carollo said.

Adoring abuelas and frightened employees

So how has Carollo remained in power despite the dysfunctional state of Miami government? At Robert King High Towers, the mystery is solved. Here, home to low-income elderly people, in one of Miami’s pockets of el exilio, is the nerve center.

Maria Campos and Lilian Pla, 75, are in charge of the teeny headquarters of the residents association. Inside, Pla — sister of Enrique Pla, drummer for the renowned Cuban band Irakere — plays Cuban ballads like “Siboney” and “Guantanamera” on an electronic keyboard. Campos cracks Cuba jokes: “A husband and wife sit in their Havana kitchen. They have no food or electricity. He opens a box that contains four new tires. She asks him, ‘Why do you buy tires when you don’t have a car to put them on?’ He asks her, ‘Why do you buy bras when you don’t have breasts to fill them?’”

They are thankful for Joe Carollo. Thankful for the 4,000 turkeys he hands out every Thanksgiving and the 7,500 pork dinners he delivers at Christmastime. Thankful that he comes for birthdays and bingo. Thankful that he “protects us and never forgets us.” Thankful that he listens whenever they call, sometimes to talk when they’re feeling lonely.

Hoy entregamos + de 2,500 pavos en el Parque José Martí a residentes d nuestro D3. Como cada año, durante estas dos semanas distribuimos pavos a personas mayores y fam d bajos recursos del distrito.Este año entregamos un total d más de 5,000 pavos. Feliz Día de Acción de Gracias! pic.twitter.com/Viec2LuKlf

— Joe Carollo (@JoeCarolloNow) November 23, 2023

“I walk around here every morning at 4 a.m. and saw that we do not have enough benches,” Campos said. “I called Commissioner Carollo, who is my friend, and the next day we had 43 new benches. We have people living on the 14th floor and it is difficult for them to use the elevator. He helps us obtain medical certificates to move them to a ground floor unit.

“We vote for him, always and forever.”

How many votes does he need? Not many. He won the 2021 election with 4,001 votes; only 7 percent of the 95,000 constituents in his district cast ballots. He won the 2017 runoff by 250 votes.

Once he’s in office, Carollo maintains his grip on government by punishing anyone who disagrees with him, according to city employees’ testimony in the Ball & Chain lawsuit. Ask former city manager Jose Garcia-Pedrosa, who was fired three times in three weeks by Carollo, and reinstated three times by commissioners before he gave up and resigned. Ask the former members of the Historic Virginia Key Beach Trust and operator of the Outdoor Center, all removed from their posts after they objected to Carollo’s proposal to move the city’s homeless population to an encampment on the island.

At least three employees said they comply with Carollo’s demands for fear of losing their jobs, jobs that lead to generous golden city pensions upon retirement.

Run or retire?

Carollo will be 70 when his term runs out. Is he planning to retire?

He’d like to have time to re-plant his garden and restock his Koi pond. Travel. Visit family. He hasn’t decided whether to run for mayor. Miami’s political insiders predict he won’t be able to resist, “and Joe can easily raise a ton of money for another campaign,” Regalado said. Carollo raised $2 million in 2021.

Carollo claims he could say goodbye to all that and wouldn’t be bored living on a farm with lots of rescued dogs and cats, which is what his wife Marjorie dreams of.

“This job hasn’t given me a life,” he said. “Majorie and I would like to retire to Shangri-La.”

Where is Shangri-La, Joe?

Carollo chuckled. A monotone chuckle, but a chuckle nonetheless.

“I can’t tell you where it is,” he said. “Because then everyone will want to move there. I’d have to become prime minister to control the border.”

Clarification: The initial version of this article was updated to detail how city staffers came to accompany Commissioner Carollo on a visit to homeless gathering spots.

Credits

Linda Robertson | Feature Writer

David Smiley | Politics and Washington Editor

Dana Banker | Senior Managing Editor

Rachel Handley | Illustrator

Susan Merriam | Graphics / Developer