Miami police shooting shows why we need to keep civilian oversight, not cripple it | Opinion

When Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a law this week that will cripple civilian police oversight panels like Miami’s, his office said, via a statement, it stops communities from driving an “anti-police agenda.”

Accountability doesn’t necessarily equate to hatred of law enforcement. In many ways, having civilians investigate police actions lends legitimacy to law enforcement among communities historically distrustful of it.

Cases like the recent police shooting of a Black man near Liberty City explain why that’s important.

On the day of the March 7 shooting, Donald Armstrong’s mother called 911 asking for help for her son who she said was having a mental health crisis. A standoff with police ensued as he stood on the porch of her Model City home. As he was tasered a second time, Armstrong stumbled off the porch toward the officers. Miami Police Officer Kassandra Mercado opened fire, hitting him six times, according to his lawyers.

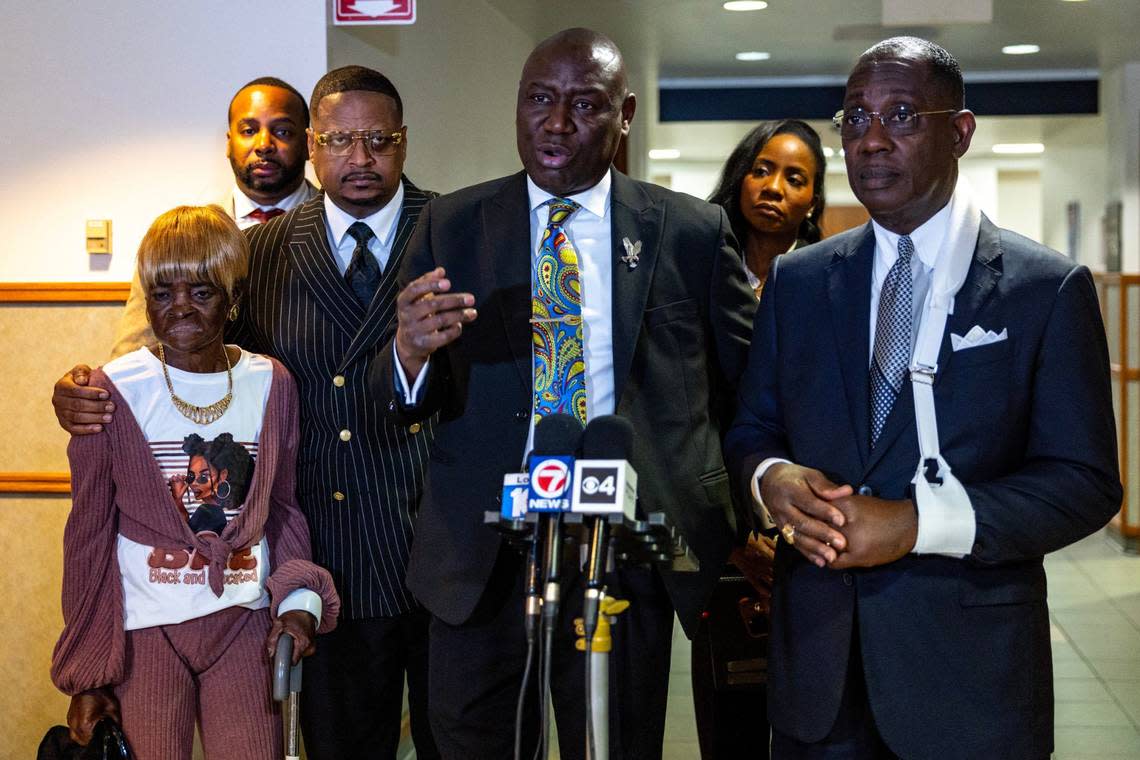

Armstrong held a sharp object that has been described as a screwdriver, a double-edged blade by police and a musical wand, the Herald reported. A police report stated he was “possibly high on narcotics,” but civil rights lawyer Benjamin Crump, who’s representing Armstrong, said police failed to intervene properly in a mental health crisis.

Armstrong, who was not killed, was charged with a misdemeanor and a felony charge of aggravated assault of a law enforcement officer. Prosecutors dropped the felony charge on Tuesday, the Herald reported.

Bystander videos of the incident have been widely shared on social media, causing outrage among residents and prompting Crump, known for taking on high-profile cases of Black people shot by police, to call a news conference.

There are many questions: How did a 911 call of a mother pleading for help escalate to a standoff? Was the officer justified in continuing to shoot Armstrong even as he fell to the ground?

A police investigation is under way and Mercado has been administratively reassigned.

The work of Miami’s Civilian Investigative Panel begins once a law enforcement investigation is closed. The panel has the authority to audit investigations or conduct its own by talking to witnesses and officers and looking at body camera footage, Director Rodney Jacobs told the Herald Editorial Board.

The panel handles more than 300 cases a year, Jacobs said. Most involve complaints of violation of police department procedures, such as officers accused of not wearing a body cam properly or engaging in high-speed chases against policy. The panel doesn’t have the power to discipline officers, only to make recommendations to the police chief.

“I like to think police chiefs like to use our office,” Jacobs said.

If the goal of police is to have accountability for so-called “bad apples,” they should welcome scrutiny. It also helps build trust with communities like Liberty City, where people have good reason to doubt that cops can investigate each other and reach fair outcomes.

After all, voters created Miami’s Civilian Investigative Panel in 2001 after a string of fatal shootings of Black men and the indictment of 13 officers accused of planting guns on suspects.

The Legislature passed House Bill 601 because of a belief that civilian panels are stacked with anti-police activists. Like cops, the panels should also be held accountable to the taxpayers funding them. In 2014, the city of Miami launched an inquiry into the CIP after Herald reporters found that budget cuts and infighting crippled the agency’s ability to hear and close cases in time.

The new law doesn’t abolish civilian police oversight panels but it does allow police chiefs or sheriffs to create their own panels and appoint all of the members. It’s unclear whether those panels would replace existing panels but that does raise the question of whether any remaining oversight panels would be stacked with pro-police rubber-stampers.

Jacobs is still analyzing the law’s impacts on Miami’s panel, but said the new rules are a “punch to the face.” They are also a blow to the long-fought battle for police accountability and the work of building trust with communities of color.

Click here to send the letter.