Medicaid expansion offers hope for those wrestling with addiction. Will it be enough?

Medicaid expansion looks more likely than ever to pass into law, and experts say it’s crucial to tackling the opioid epidemic in North Carolina, where there has been a rise in the use of deadly synthetic drugs such as fentanyl.

Those same experts agree, though, that Medicaid expansion alone is not enough to curb the rising rate of deaths.

“North Carolina is known throughout the country for being a desert of available services,” said Ward Blanchard, president and founder of the Blanchard Institute, in Charlotte, which provides outpatient treatment to about 300 people a year. “… Licensed residential centers and detox centers are few and far between.

“People are dying in the meantime.”

If state leaders succeed in passing a massive expansion of health insurance for low-income people, North Carolina could struggle to meet the demand from the many additional people who will qualify for Medicaid.

“If you are insured, but there’s no addiction provider in your community, or there is but that provider doesn’t take Medicaid, then insurance isn’t enough,” said Alex Gertner, a psychiatry resident at UNC hospital. “Even if you’re lucky enough to find one, it doesn’t mean that they’re accepting new patients.”

The need for more providers is the reason Sara Howe, CEO of Addiction Professionals of NC, applauds lawmakers for taking another step alongside Medicaid expansion: loosening a state law that determines where hospitals, clinics and other health care facilities are built. The move to scale back the state’s “certificate of need” law will make it easier for providers to open.

“They recognized that without an adequate network (of providers), we will be giving false hope to people,” Howe said.

“By having this access and coverage, we’ll hopefully start to stem the tide. It will take time but I hope this is the first step,” she said. And what’s more: “It will save the state money — in spades.”

How Medicaid expansion could help

As her addiction to crack and powder cocaine drove her life out of control, Dare County native Kari Haywood knew one of two outcomes awaited her if she didn’t get help: “I was either going to be in jail — or dead.”

With financial help from her parents — and from the Blanchard Institute in Charlotte — she got treatment and wound up taking a different path. Now 45 and living in Charlotte, she has been in recovery for more than four years.

Others, she knows, have not been so lucky. She has lost about 20 friends to addiction, she said. Many of them wanted to quit, she said, but they didn’t have the money for treatment. They worked in restaurants, on fishing boats and in other jobs that didn’t provide health insurance.

“It was always like, ‘Kari, I don’t have the money to get help,’ ” she said. “When you’re denied help because you don’t have the money, people are like ‘(expletive) it. We don’t have the money. So why bother?’ ”

For people dealing with addiction, she said, the difference between life and death all too often boils down to money. A 30-day inpatient treatment program typically costs between $5,000 to $20,000, depending on the clinic, according to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics.

“It’s very frustrating and it makes me mad,” she said. “There’s never enough money for them to stay in rehab and get the help they need.”

Medicaid expansion, if passed into law, would open the door to health coverage to about 600,000 low-income North Carolinians. House and Senate Republicans reached a deal on expansion after years of resistance followed by months of negotiations. It’s contingent on an expansion bill and a state budget bill both becoming law in the coming months.

Haywood said expansion could offer hope to many who need help.

“It would be great for them to know they don’t have to stress about money,” she said.

Dr. Michael Baca-Atlas, a UNC Health doctor who provides substance use treatment for underserved groups at WakeBrook Behavioral Health Facility in Raleigh, said many of his patients are uninsured and struggle to afford medications they’ve been prescribed to help manage their addictions. Some patients who can’t afford it have tried to space out how frequently they take the medication, he said.

He said his patients typically pay more than $100 for a month’s supply of suboxone, a medication often used to treat narcotic addiction. Medicaid recipients can buy that same prescription for a copay of $4.

“It’s a game changer,” he said.

“We do some amazing things in the state health care-wise, but not having Medicaid expansion during the real height of the fentanyl epidemic put us behind in terms of treatment,” he said.

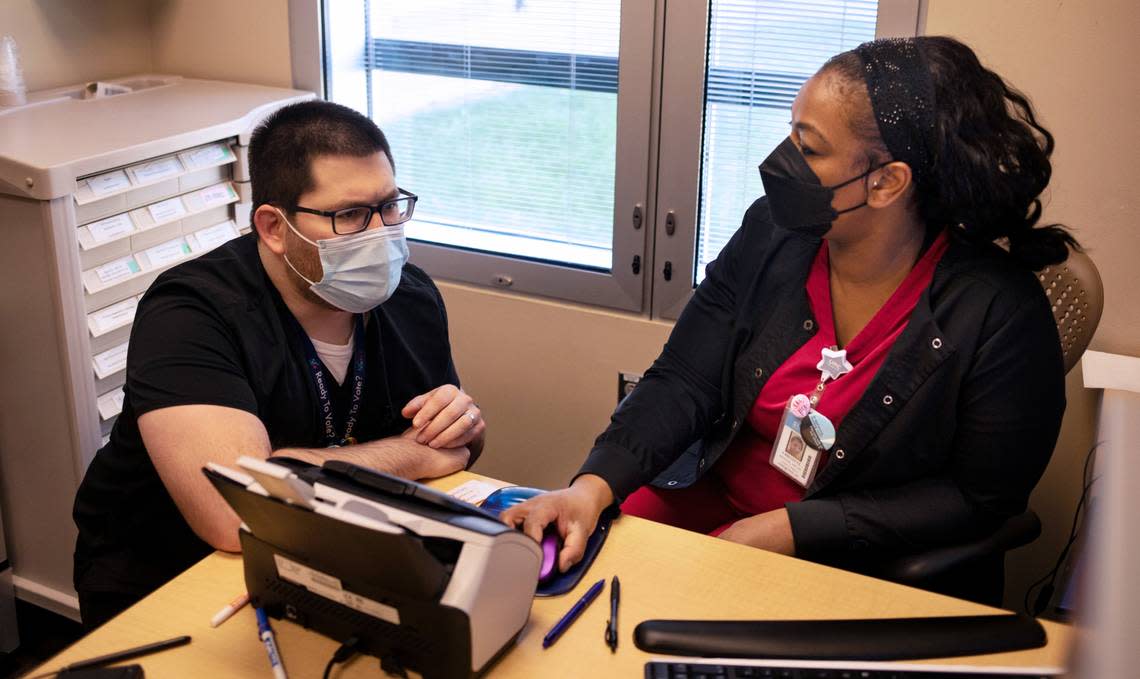

Niana King, treatment services coordinator and backup program director for the New Season methadone clinic in Charlotte, said many people who struggle with substance abuse can barely afford to get to the clinic — let alone pay for treatment there.

Medicaid expansion should change that, she said.

“If more people can get the help they need, we’ll have less people on the street, less people turning to drugs, less people not being able to get the health care they need,” she said.

At the McLeod Centers for Wellbeing, which has nine treatment centers, most of them in the greater Charlotte region, about 25% of the 6,000 people treated each year now qualify for Medicaid, President Mary Ward said. With Medicaid expansion, Ward hopes that will rise to 50%.

Research shows that Medicaid expansion is linked to better outcomes for those with substance use disorders. One study found that Medicaid expansion states had an 18% increase in admissions to opioid treatment facilities.

During the first year of expansion in Virginia, the state saw a 79% increase in people receiving care through an addiction treatment benefit offered by Medicaid.

Overdose deaths rise

Medicaid expansion comes none too soon, Ward said. With the rise in synthetic drugs like fentanyl, more and more people are dying.

One way or another, society will pay for this problem, she said.

“If we can’t give the treatment, they’re going to overdose,” she said. “And if they don’t die, they’re going to end up in the hospital. And who’s going to pay for that?”

In 2021, overdose deaths in North Carolina increased 22%, with 4,041 people losing their lives. This was the highest number of overdose deaths on record, according to a report from the Department of Health and Human Services. More than three-quarters of overdose deaths in the state likely involved fentanyl, often in combination with other substances, the department said.

Randy Abbott, an advocate who lost his daughter Vanessa to an overdose, said many with substance abuse problems relapsed during the pandemic as in-person treatment and group meetings became more difficult.

“Once someone has a return to use, it’s like starting at ground zero again. Maybe even worse,” he said.

A shortage of providers

The availability of mental health and substance use resources, also referred to as behavioral health resources, varies by county. While people without any insurance have the most trouble getting help, those with Medicaid, and even those with private insurance, also may face difficulties.

All but three North Carolina counties — Davidson, Cleveland and Orange — had shortages of mental health resources in 2022, according to federal data.

Freida MacDonald sees these shortages in her job as a resource advocate with Alcohol/Drug Council of NC. McDonald also founded Know Hope North Carolina, which puts up billboards across the state showing people who have died as a result of overdoses.

“In a lot of the rural areas, it’s extremely hard because they may not even have anywhere that’s close to where they live,” MacDonald said. “And do they have transportation? Do they have a license? All the things that it takes to get to where they need to be? So it gets very complicated within our state.”

MacDonald began helping people with substance use disorder find resources after she lost her two sons, both aged 24.

Stephen, the eldest, died in a shooting during a robbery. Michael, coping with grief after his brother’s death, began to use pills and died of a fentanyl overdose while in a recovery center in Wilmington.

“I was pretty much isolated as to, where do I go with this? What do I do? How do I get him help? I didn’t really know anybody at the time. And so it’s really my desire for when people are struggling like that, that they know where to go,” MacDonald said.

North Carolina’s certificate of need process, which determines what medical services are available across the state, makes it difficult for new providers to start up, Blanchard said.

Under the Medicaid expansion deal cut by state lawmakers, this may change. They have agreed to allow construction or expansion of certain facilities without a certificate of need from DHHS. The facilities would include those that provide inpatient treatment of behavioral health problems and chemical dependence.

Blanchard knows about the problems from personal experience. About 20 years ago, he became addicted to prescription painkillers while being treated for a serious illness. When he sought treatment in 2006, he and his family could not find a single residential treatment facility that was appropriate for him in all of Eastern North Carolina, where he lived at the time.

So he had to go to Virginia for treatment.

To fix some of the shortages, particularly in rural areas, the state needs to look at pay for all behavioral health care workers and provide incentives for these workers to move, said Lisa Zerden, deputy director of UNC-Chapel Hill’s federally funded Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center.

State behavioral health facilities had 3,684 vacant positions in 2023, representing an increase of more than 225% from 2017, according to a state report. Across all facilities, 2,449 fewer people were served in 2021-22 than in 2019-20 — a drop of more than 30%.

Zerden also said the state needs to look at increasing Medicaid reimbursements that providers get for behavioral health services. This would encourage more providers to accept Medicaid, she said.

Kelly Crosbie, a DHHS division director, acknowledged the need to “make sure that we have enough providers and workforce and that they get paid an adequate rate.”

The Medicaid expansion bill in the works in North Carolina would increase Medicaid reimbursement rates for hospitals.

Pain pipeline

While moving things off of a truck, Ricky Clay felt a painful pop in his neck.

He went to the doctor and was told he had spinal stenosis, which puts pressure on the spinal cord and the nerves.

At that time, Clay, now 44 and living in Wilmington, had Medicaid health insurance, as he was married and had children. In North Carolina, Medicaid currently covers a parent or caregiver whose income is up to 41% of the federal poverty level.

Expansion would extend coverage to all adults with income below 138% of the federal poverty level.

Medicaid covers a wide range of services for substance use disorder in the state, including screenings at primary care offices, therapy sessions from a clinical addiction specialist, 28-day medical detox programs, daily programs, and medication-assisted treatment, according to Crosbie.

Expansion would also provide access to other potentially life-saving health services.

For his neck pain, Clay started going to a pain specialist. He got medication, spinal taps and injections but the pain just kept getting worse.

Things continued downhill. He split with his wife, who took their kids. As he no longer had custody of his kids, Clay fell into the Medicaid “coverage gap”, which refers to people who do not qualify for Medicaid and make too little to receive subsidies to help them buy insurance on a federal marketplace.

With money he made in his job as an electrician, he worked to pay for pain medications out of pocket. But five years into taking the medications, he started becoming addicted and requiring more medicine.

As the expenses for his medicine and child support piled up, he started buying other, more potent street drugs and selling some of his medicine, he said. That landed him in prison.

While in prison, he received a much-needed emergency surgery on his neck.

“That’s the only reason I got the surgery that I had. If I was still out there on the streets, I’d never have had this surgery and I may even be paralyzed by now,” Clay said.

Hospitals often have to provide uncompensated care to those without insurance. The state, which runs facilities and offers care, must also pick up the tab.

Now out of prison, Clay continues to work and advocates for expansion, despite having liver problems due to continuous pain medication, and needing knee and lower back surgeries. He no longer takes pain medication and still does not have insurance. He said his children and grandchildren help him stay in recovery.

“If I got Medicaid, it would help me out. But I am at the point where there’s nothing they can do for me but make me comfortable,” he said. “I deal with a lot of severe pain”

“I know there’s gonna be other people like me if they don’t have insurance to help them out,” Clay said. “They’re gonna become severe addicts because of situations like I was put in.”