Mayor de Blasio’s policing legacy: distrusted by both NYPD cops and reformers

It was a defining moment — police officers, shaken with grief and anger after the point-blank Brooklyn execution of officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, turning their backs on Mayor de Blasio when he arrived at Woodhull Hospital.

The mayor, observers say, pivoted sharply after that fateful day in December 2014, failing to radically reform the nation’s largest police force as promised and instead lavishing praise on the same cops who he’d said two weeks earlier could mistreat his biracial son Dante.

Cops and their union leaders — “people he was never going to win over,” as one former aide put it — wouldn’t forgive de Blasio and said his subsequent support was insincere, a move to save his political skin.

And when violent crime surged over the last two years, he stopped regularly appearing at NYPD press conferences that once featured signs proclaiming New York “the Safest Big City in America.”

Now, in the final hours of his mayoralty de Blasio’s legacy on policing is being assessed — and it’s not pretty.

“He came in with an overwhelming sense of optimism and is leaving with a pretty staggering degree of pessimism,” said Corey Stoughton, a top lawyer with the Legal Aid Society. “I really can’t think of a single example of the kind of leadership from City Hall on police issues, the kind of leadership needed to re-imagine policing.”

“I’d give him an ‘F’,” said Paul DiGiacomo, head of the detectives union. “Because of his actions and his ideology those two police officers were executed. That set the tone for people to attack cops and it’s still going on today,”

“I enthusiastically supported de Blasio in 2013 on the mistaken assumption that his campaign rhetoric was sincere,” said civil rights lawyer Joel Berger. “By 2017, I wouldn’t even vote for him. He was a complete failure.”

Former de Blasio aides and officials say the mayor pushed to add Blacks and Latinos to the upper echelons of the NYPD and that he deserves credit for various police training initiatives, such as dealing with the mentally ill and overcoming implicit biases.

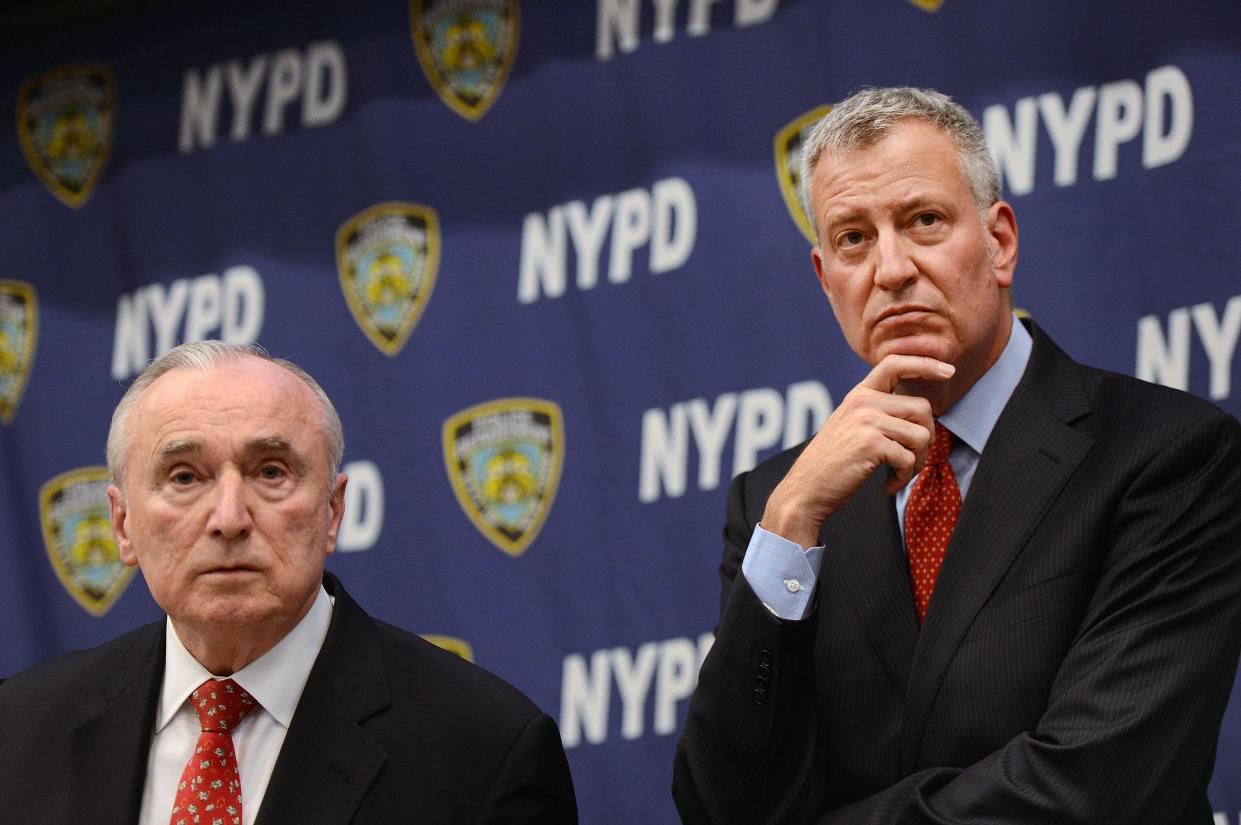

And they, as well as a number of police officers, credit Hizzoner for tapping Bill Bratton as the first of his three police commissioners, ushering in a tone that sharply contrasted with 12 years under former commissioner Raymond Kelly.

Stop and frisks, which had been declining since 2011, plunged more than 90% under Bratton and the department turned to “precision policing,” focusing on the known violent criminals while making far fewer arrests and issuing far fewer summonses.

“I’m telling you that in Black communities that meant something,” said a Black officer. “That’s something that makes a big difference in a lot of minority communities.”

De Blasio said during a farewell press conference Thursday that his efforts on policing will be fully understood “in the years ahead.” The pandemic, he said, had disrupted successful reforms that drove down crime for six years in a row.

“We re-bonded police and community in many ways, created an entirely different approach to policing, focused on the relationships – and the positive relationship between police and community members,” de Blasio said.

But Rep. Nicole Malliotakis (R-Staten Island,) who ran against de Blasio for mayor in 2017, said less enforcement came with a cost — a spike in quality of life offenses such as turnstile jumping and panhandling. De Blasio’s support of bail reform has been a recipe for disaster, she added.

“He appointed the criminal court judges and many of them have refused to set bail,” she said. “He created an environment where laws were no longer being enforced and cops were told to lay off.”

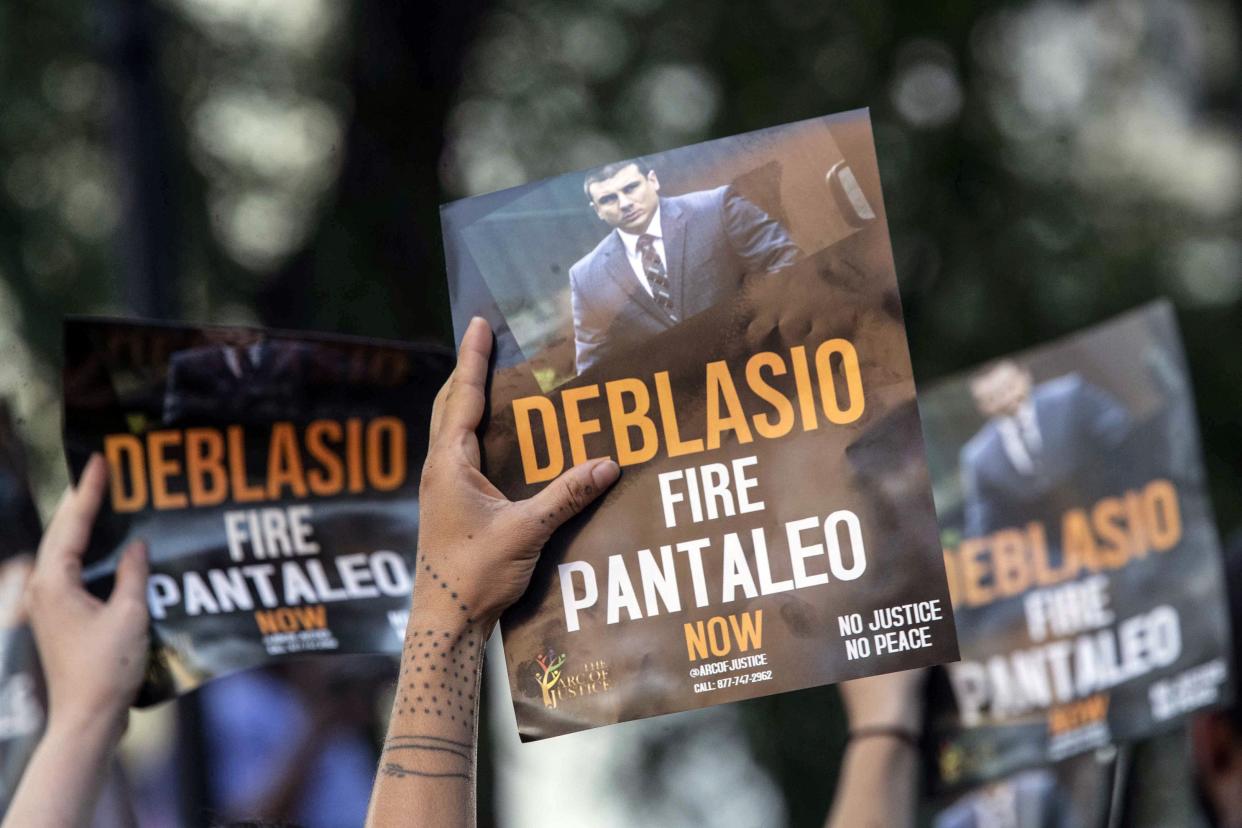

It was a suspected quality of life offense — selling untaxed cigarettes — that resulted in the police killing of Eric Garner on Staten Island in July 2014. Critics say de Blasio’s response to the crisis highlighted his failure to be a strong leader.

It took the NYPD five years to fire Officer Daniel Pantaleo for using a banned chokehold on Garner.

The long wait — at a time when city lawyers were pushing back against attempts to repeal 50-a, the state law that for four decades shrouded police disciplinary records in secrecy — cost de Blasio political capital among progressives and advocates who supported him.

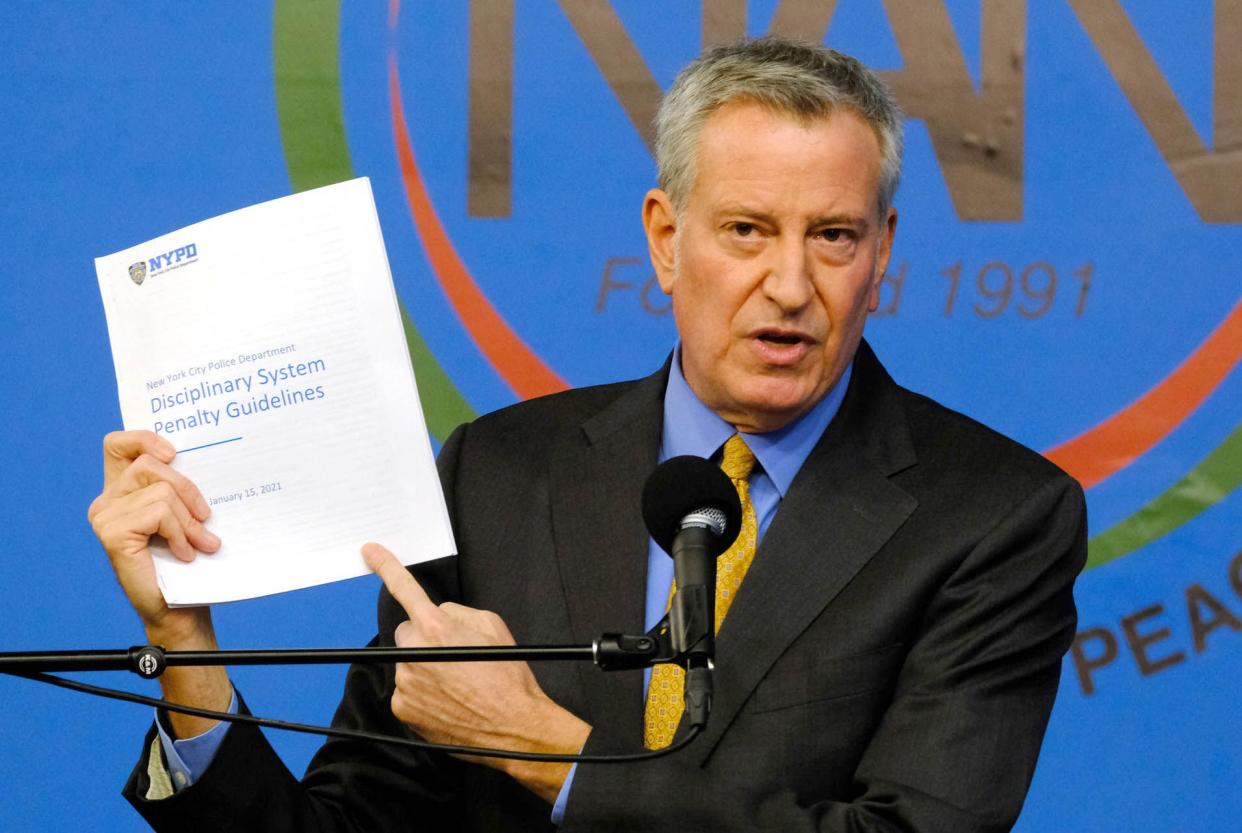

Then came the George Floyd protests — weeks of rallies for racial justice that in a number of instances devolved into caught-on-camera riots, with police cars set ablaze, officers attacked and stores vandalized. Dozens of cops used improper, heavy-handed tactics against protesters, according to the Civilian Complaint Review Board.

The NYPD pointed to several instances in which cops were disciplined, but it otherwise said it excelled under extreme circumstances, with the mayor “nodding along,” in the eyes of a former City Hall official.

The mayor later changed his tune, apologizing for aggressive police tactics cited in a DOI report that slammed the NYPD for a lack of a “clearly defined strategy.”

It was too late to assuage his critics.

City Councilman Brad Lander (D-Brooklyn) said for many people evaluating de Blasio, the starting point is police accountability.

“Will these family members who have lost loved ones who were killed by NYPD officers have a real investigation, be able to trust what they’re being told, have it happen in a timely fashion?” Lander, the incoming city comptroller, said. “When the CCRB does bring charges, is there any reason to believe that they’ll be taken seriously for officers who stood by or in some cases lied about what happened? Will there be accountability? And listen, the answer has generally been ‘No’ to all of those things.

“The system has failed those families much, much, much more often than it has provided accountability.”

Eugene O’Donnell, a former cop now teaching at the John Jay School of Criminal Justice, said the NYPD was never the “marauding group of racist cops” de Blasio made it out to be. He said de Blasio’s rhetoric — along with the “defund the police” movement and laws making it more difficult to make an arrest — have irreparably hurt the city.

“He took a safe city and made it much less safe — and the police have been disempowered,” O’Donnell said. “They’re just trying to get through the day without any conflict — and that’s a recipe for disaster.”

Fellow cop turned academic John Eterno of Molloy College agrees, noting that the drop in street stops is not just a byproduct of different department priorities — it’s also an indication of how cops feel.

“They’re not doing their jobs,” he said. “They’re afraid.”

But don’t tell that to Jonathan Valentin, a 25-year-old Latino from Flatbush, who says cops still abuse the use of stop and frisk.

“Have I seen any changes, especially with stop and frisk? he said. “No.”

Edward Kavelier, 70, of East Flatbush, said much the same.

“I’ve known people who got locked up for minor stuff that ended up doing big time,” the retired sanitation worker said. “It hurt a lot of Black young boys who went to jail. They shouldn’t have been stopped at all.

“That’s my main gripe.”

With Ellen Moynihan