Mark Patinkin in Israel: Getting a tour of paralyzed Brown student's hometown

I’m on the bus to Ramallah, a hub of the West Bank, and as far as I can tell, I’m the only non-Palestinian among 40 or so aboard.

It’s 8 miles from Jerusalem but the trip takes more than an hour, with a checkpoint halfway and all roads but one closed to a metro area of almost 300,000.

That is life on the West Bank.

I’ve come here to see Hisham Awartani’s world. You no doubt have read about Hisham. He grew up in Ramallah and was one of three Palestinian college students shot in Burlington, Vermont, for the crime of speaking Arabic and wearing black and white keffiyehs.

It brought the conflict’s echoes to my own neighborhood in Providence, where Hisham, now paralyzed from the waist down, is a junior at Brown University.

I had emailed his mom, who is with him as he recovers in Massachusetts, about hoping to visit Ramallah. She suggested I see Aboud Ashhab, one of Hisham’s best friends, the two, now 21, having shared both a West Bank childhood and the last three years at Brown.

Aboud said he was honored that I would make the effort to see him here, where he’s home for semester break, but he was cautious, too, aware that journalists have not always been kind to Palestinians.

But he loves Hisham, and both feel the importance of showing the human side of a people too often vilified. Maybe, he hoped, this would help soften the hate.

Finally, I’m in Ramallah, stepping into a lively urban vibe. The central streets are bustling, with 10 times the buzz of Bethlehem. But the war is here, too, a huge display at the city center showing the faces of 60 children killed in Gaza. “We are not numbers,” it says.

As I wait for Aboud, notepad in hand, a classy gentleman asks if I’m a journalist. Guilty. His name is Amad Omar, and it turns out he spent a few decades as a jewelry store guy in Chicago, where I was born, but he came back in 1998 because Ramallah is home.

I tell him the city seems alive, and, yes, he says, it’s a wonderful place, except when “something happens.” Like now, with the border sealed and jobs lost. But I came on a good day – on others there are strikes against the Israeli crackdown.

Yet the crowds, says Amad, show that Palestinians know how to keep living.

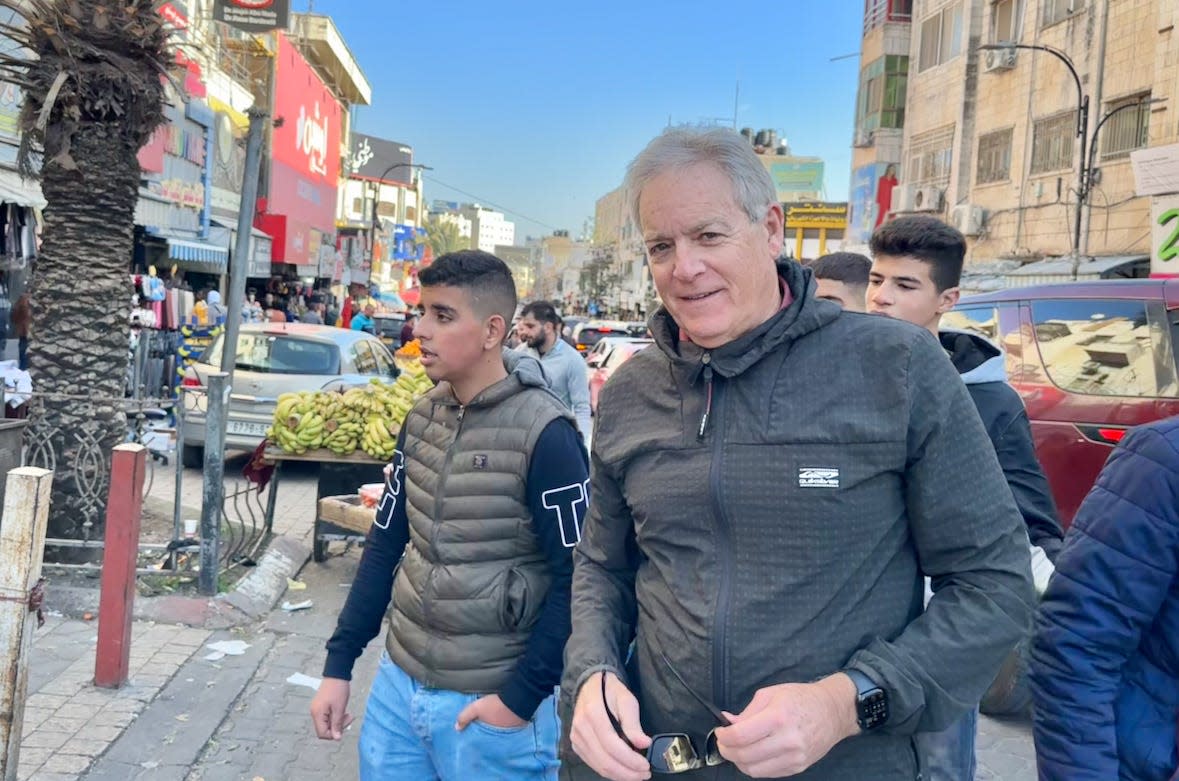

Aboud soon arrives, a polite young man who can’t wait to show me Ramallah. I tell him I love how alive it is here.

Aboud shakes his head. It used to be much more. Some of the sidewalk vendors are skilled tradesmen who've been blocked from jobs in Israel, now barely getting by selling vegetables.

Things here are hard, says Aboud.

But he’s so proud of his city.

He has twin 18-year-old brothers who are also about to go Ivy, one at Penn, the other at Brown, quite a trajectory for young men from Ramallah. Like Hisham and Aboud, they attended the remarkable Ramallah Friends School, unrivaled on the West Bank, where kids learn and dream and rise.

As we walk, we pass flavorful coffee and lunch places. Aboud wants me to see a favorite where he and Hisham would talk and play cards as they planned their young lives.

Earlier, when I told people I was heading to the West Bank, most said the same two words.

Stay safe.

They didn’t need to. I haven’t seen another non-Arab face in the thousands we’ve walked by, but I feel zero threat.

We sit for tea and coffee where he and Hisham sat for the same. It’s a second-floor café called Succariya with a balcony and Arabesque feel.

I ask about Hisham’s shooting. There’s no question in Aboud’s mind it’s because Arabs are dehumanized.

Arabs, says Aboud, are seen as backward and intolerant. But he says it’s not like that, and he’s right; many women around us wear hijabs, but many don’t, and no one seems to mind. There are churches, too.

“We went to school with Palestinian Christians,” said Aboud. “We’re not a Muslim monolith; we’re a diverse group of people.”

He likes his coffee the strong Arabic way. It reminds him of how Hisham used to make Arabic coffee in the Brown dorm where they were roommates.

I ask him to tell more about what Palestinians face.

“There’s no civil law for Palestinians,” Aboud says. Even those arrested for speeding go to military tribunals, and thousands are held without trial for reasons not always shared.

Because of the need for permits out of the West Bank, it has never been easy for Aboud to see his aunt and cousins who live in Jerusalem.

“Now,” he says, “it’s impossible.”

Hundreds, he said, have been shot in raids and at checkpoints by Israeli soldiers since Oct. 7, including a Louisiana-born 17-year-old Palestinian American named Tawfiq Ajaq the day I was there.

The other day, says Aboud, while driving, he suddenly saw a checkpoint at a random place he didn’t expect.

“Had I not hit the brakes early,” he said, “I might have been shot.” He paused. “I would have been shot.”

I tell him he doesn’t seem angry, and it’s true; Aboud is a mild-mannered young man.

Palestinians, he says, hear that a lot, and it’s a form of fearmongering. It’s a false impression, he tells me, that people who talk about oppression are radical.

Even Aboud’s gastroenterologist dad was arrested years ago as a student while protesting the occupation and was held for six months.

“It’s a never-ending story,” Aboud tells me. “It’s why they wanted us to study in America. They wanted us to get a safe education.”

The latest: International Court of Justice orders Israel to take steps to prevent Gaza death and destruction

He pauses.

“Of course, that flipped on its head when Hisham was shot.”

We moved on to Aboud and Hisham’s favorite lunch spot, Abu Johnny, a barbecue grill with sidewalk seating.

I ask how Hisham is doing in rehab.

“I talked to him a few days ago,” said Aboud. “He’s hoping to come back to Brown in February and start the spring semester.”

And why does Aboud love Ramallah and the West Bank so much?

For one thing, he said, it’s more social than America – you start the day with no plans and end up hanging with 10 or 12 friends. Then he observed an amusing difference. The West Bank has cleaner, um, facilities. Aboud and Hisham are still freaked out by how gross America’s public bathrooms are.

We’re brought our dishes, big ones, of spicy chicken and lamb kebabs, with hummus, vegetables and hot shatta sauce.

I am learning there is no such thing as small portions with Palestinians.

How, I ask, are Hisham’s spirits holding up?

His physical therapy is going well, and he’s recovering mentally. Indeed, most of Hisham’s public statements have not been about himself. Even when it’s just the two of them talking, Hisham says he’s better off than people in Gaza, where some have limbs amputated without anesthesia because there isn’t any. Hisham wants the focus there.

Where, I ask, does his strength come from?

Aboud answered with the Arabic word “sumud.” It means steadfastness, which Palestinians get from what they’ve been through.

“Overcoming adversity?”

Aboud says that word is too general.

“It’s overcoming oppression and violence,” he says.

He added: “People have lost family, land and houses – but not the pride in who they are.”

Finally, it’s time for me to head back. On our way to the bus, we pass their favorite ice cream parlor, called Rukab's.

“Me and Hisham love this place,” says Aboud. “It’s the best ice cream in Palestine.”

Aboud gets the dark chocolate, Hisham pistachio. They miss Rukab's at Brown.

Aboud would be heading back there soon, but he needs to leave three days early to get through the Jordan border to Amman’s airport. He’s not allowed to fly out of nearby Ben Gurion by Tel Aviv.

It’s almost night when my bus back to Jerusalem gets to the checkpoint. I exit, show my passport, go through a metal detector, then wait a half hour in the dark for another bus on the other side.

Aboud is nice enough to check in on me later by WhatsApp.

He thanks me for coming to see his world, and Hisham’s.

He’s happy I’m back in Jerusalem.

He never mentions that despite his Ivy pedigree, and aunt and cousins living here, as a Palestinian man, it’s a place he’s not allowed to go.

Mark Patinkin is traveling to Israel personally and is not sponsored by or affiliated with any organization. He will report firsthand from the region as he has done for the last four decades through his award-winning journalism. He can be reached at mpatinki@providencejournal.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Friend of Brown student paralyzed in shooting leads tour of Ramallah