Mark Arax keynote speech: A reckoning on the day of the naming of H. Roger Tatarian School

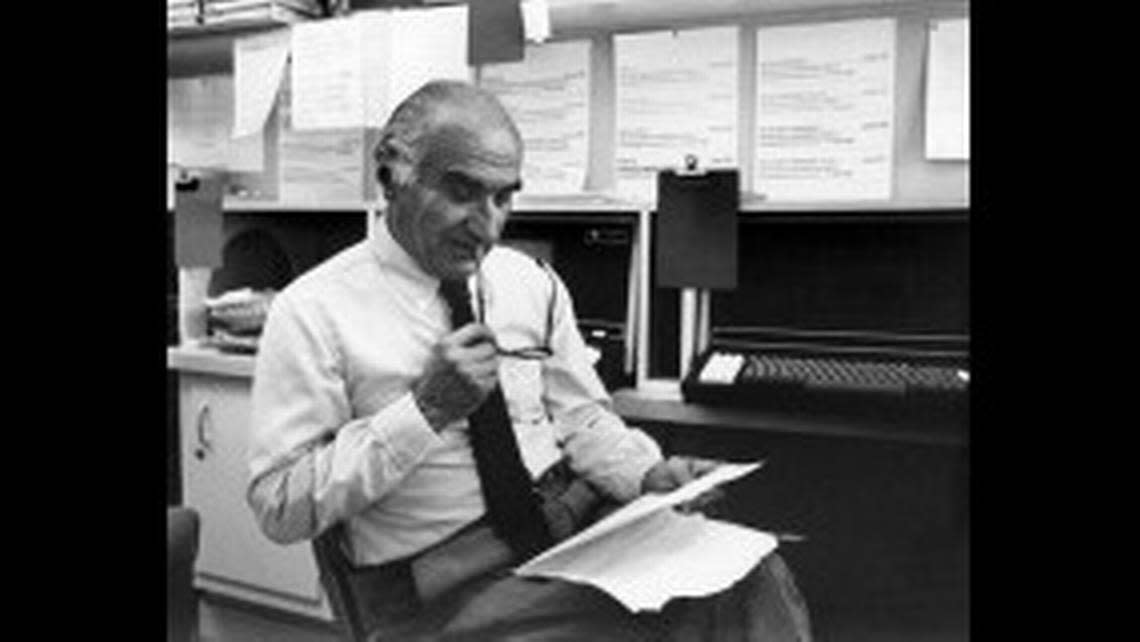

Author and journalist Mark Arax delivered this keynote address at the Sept. 7 dedication of H. Roger Tatarian Elementary School in Fresno.

On this day of ceremony and celebration, I’d like to begin my remarks on a somewhat discordant note. I believe H. Roger Tatarian is looking down on this gathering of good people, well-intentioned people, with that famous scowl of his.

He was a wise man with a strong sense of himself but outwardly he was modest to a fault. So much so that I don’t believe he would have wanted a school named after him. I think he would have thanked us for suggesting such a thing, but he would have tried to prevail upon us that it wasn’t necessary, that if we did our due diligence and looked deeper into the matter, we could certainly find someone else more deserving, more fitting, for the honor. Thanks, he would tell us, but no thanks.

All I can say in my defense is that when my sister, Michelle Arax Asadoorian, called me last spring with her idea to push for a school in Fresno Unified that would finally be named after an Armenian, the only right person I could think of was H. Roger Tatarian.

I apologize, Mr. T.

I grew up not a mile from this ground. When I headed off to Fresno State as an 18-year-old, it was with a chip on my shoulder and a get-even in my heart. My father had been murdered in this town only a few years before, and the crime, which would go unsolved for 30 years, was a window into a history of civic corruption, greed, small mindedness and bigotry without disguise. This valley was grapes and apricots and peaches and plums, but it was also the plantation brought from the South to the West, a place of owners and their imported workers, of environmental and human wreckage.

I did not go to Fresno State in search of a father figure, but I found in the Journalism Department at least four of them: Art Margosian, Dayle Molen, Jim Tucker and Roger Tatarian. The last one became my mentor, the man who would redirect the path of my life, knock the chip off my shoulder and help me understand that what was in my heart wasn’t revenge but the desire to tell a story.

First, he passed to me some tricks of the trade. A writer, he told me, has 30 minutes to capture the attention of a book reader, five minutes to capture the attention of a magazine reader and all of ten seconds to capture the attention of the newspaper reader. You had to grab the reader by the throat and not let go.

The device by which to do this was the lead, the first few paragraphs. Imagine the reader looking down the deep and dark of a cavern, a subterranean world. Your lead, he explained, was the light that illuminated the way.

If you got stuck somewhere in the telling of your story, which a writer always did, just return to the sentence or sentences you had already managed to put on the page and read them; this will unstick you and return you to the flow, he said.

When you read your story to yourself, don’t read it with your eyes alone; read it with your voice aloud. To hear your sentences was to tell you where they fell flat, stalled, hiccuped. The eye deceived. The voice exposed all.

I began to hum when I wrote, listening to the words to hear if they smoothed into a cadence, a beat, a rhythm. Writing at its finest, he said, was music.

Finally, he advised, you won’t find good stories in the office, at the other end of a telephone. Get out into the world beyond your world.

Slowly, always modestly, over lunch at the Hunan Restaurant or during dinner at his house on old Van Ness, a meal prepared by his lovely and worldly wife Eunice, he would let loose some of the details of his own life.

His father was a proud maker of shoes. His mother, a quiet but determined force, tended to all matters of the home front. His parents had come from Bitlis, a place in Anatolia where Armenians had lived for at least 3,000 years, long before the Turks arrived. This was where the family of William Saroyan came from. Indeed, the Tatarians and Saroyans now lived across the street from each other. They had left a land of genocide only to arrive in a land invented by genocide — California.

They were shunted to the ghetto along the railroad tracks: Armenian town. Oddly they were called Fresno Indians. Maybe because the real Indians had been made to vanish, and it was hoped that with enough daggers directed at them, the Armenians might follow.

It was not an easy place to call home. Restrictive real estate covenants banned them — and Blacks, Asians and later Mexicans — from living on the good side of town; kids and teachers poked fun at the odd smells their mothers packed into their lunch boxes. They might have been the best students in class, but the honor of president or graduation speaker could not go to them.

And yet it was here in Fresno Unified, at Longfellow Junior High School on the far southside, that 12-year-old Roger found the warmth and guidance of two teachers whom he would never forget. They altered the course of his life.

He WAS the class president at Roosevelt High School. He WAS the editor of the Collegian at Fresno State. He WAS chosen as speaker for his class at the graduation ceremony. “Everybody adored him,” his wife Eunice, who was his classmate, recalled. “He could do no wrong.” He could not, however, get hired at The Fresno Bee. So he signed on with the United Press, the news wire service, first in Fresno and then San Francisco as a glorified errand boy, and then onto the Phoenix bureau as a full-time reporter.

Hrach Roger Tatarian. That was his name and the byline he used on his first big story about the world’s first nuclear test explosion, in the desert of New Mexico. His editor in New York kept sending back the message that his copy was coming over the wire with his name garbled. “What the hell was Hrach?”

“Just call me Roger,” he replied.

From there, his rise was quite nearly meteoric. Washington D.C, London, Rome, news editor for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, a promotion to New York as the managing editor and then, in 1962, his selection as Editor-in-Chief of United Press. He shaped the coverage of the biggest stories in the world from 1941 to 1972. He was a member of the first class to be inducted in the Journalism Hall of Fame in New York City alongside Walter Cronkite. Then a heart attack brought him back home to Fresno and a teaching gig at the Journalism Department at Fresno State on April 13, 1972.

Six years later, I walked into his classroom — 10 minutes late. I had a proper excuse. On a side street next to the campus, I had locked my keys in the car, a Firebird Formula 400 that had belonged to my father. The engine was running, and I was forced to break into it with a wire hanger to turn it off. As I explained the circumstances of my tardiness, Mr. T shook his head and told me to sit down.

The next class session, I was late once more. I had locked the keys in my Firebird again. No hanger this time, I had to leave the engine running. He listened to my woeful tale, removed his owl glasses and froze me with an angry look.

“Do you think I’m going to buy that cock and bull story a second time? And if it happens to be true, by God, Mr. A., get your act together.”

During those years under his tutelage, we were routinely winning the Hearst writing competitions, the college version of the Pulitzer Prizes. The Journalism Department at Fresno State ranked second in the nation. I went onto graduate school at Columbia University and then landed my first job at the Baltimore Evening Sun. I would call him on the phone with my biggest stories, and he would edit them line by line, just by hearing my voice.

I returned to California to work for the Los Angeles Times and then earned my first book contract, to write a memoir about my family’s journey out of genocide, exile in Fresno, my dad’s unsolved murder. It took me five years. When I finished, we celebrated over lunch at the Hunan.

That day, I asked him a question that a younger man should never ask an older man.

“How fast did it go by? I wondered, meaning life.”

“You want to know how fast?” he asked me. “It went by like this,” he said, snapping his finger against his thumb. “It went like this.” Snap.

He never had a chance to read “In My Father’s Name.” He died a few months before it was published. That summer of 1997, when I happened to be driving south on Highway 99 and found the Boys of McFarland, cross country champs, running through the almond orchards on a cloud of dust, like angels, I wrote their story with Mr. T’s voice in my head.

It is fitting what we have done here today, the taking down of one name and the rising up of another name. It was not without pain. No reckoning with the past, no redress of historical wrong, ever is. It was an exorcism, of sorts. J.C. Forkner was the father of the racist real estate codes that banned Armenians and people of color from living on this side of town for 50 years.

What is taking place this morning on these grounds is an act of decency, an act of justice. I thank the school board. I thank Superintendent Bob Nelson. I thank those who worked tirelessly alongside us, especially Jim Boren and Marshall Moushigian, to make this happen. You honor one of Fresno Unified’s finest. And you honor Fresno Unified’s own past.

If this sounds not quite true, here is what Mr. T wrote in a Bee column on Oct. 12, 1987:

Muriel Sherwood taught Spanish at Longfellow Junior High. Miss Sherwood was easy to fall in love with: nature had given her many advantages, and at 12 you had vague ideas what they were. But Mrs. Pratt was the one you worshiped. Everyone remembers the one teacher who most profoundly influenced his or her life. For me, it was Ruby Johnson Pratt, vice principal at Longfellow. She let me range at will through the library during summer vacations and, as advisor to the Longfellow Poet, it was she who kindled my interest in journalism. Some people may never forgive her for that, but I will never cease being grateful to her. It is somehow offensive that no trace remains of the place where she taught. So, this year, like last, I will wait until a foggy November or December day to drive slowly down Hazelwood and tell myself that it is only because of the fog that Longfellow Junior High is no longer visible.

H. Roger Tatarian Elementary down Valentine Avenue. It is visible.