Many older adults in Wisconsin have serious mental illnesses. Is society ready to support them?

MIDDLETON – Dylan Abraham sat in a jail cell thousands of miles from his Madison hometown, bracing for what would come next. He knew he was not himself, yet he couldn't ease the terror intruding on his thoughts.

Abraham tried to understand what had happened, why he'd confessed to murders he did not commit. His moments of clarity clattered against delusional thoughts of a world plotting against him.

Being in jail helped none of this.

Earlier, two police officers had arrested him for a public outburst at the grocery store where he worked. He'd convinced himself over a period of a week that his coworkers had been conspiring against him, a paranoia that boiled over when he couldn't find his apartment keys. He suspected a friend's brother stole them, so he ran in a rage to the store where he worked. There, he yelled and screamed at the brother until police arrived.

It was May 2, 1974, a Thursday. Typically, the age of schizophrenia onset in men is their late teens. Dylan was in the sweet spot, 18.

Today, he is 68.

In his retelling, police cuffed him and drove him around all night, calling him a murderer and a rapist, pressuring him until he finally caved, confessing to a string of murders without evidence.

“I was so delusional and ill that I confessed to crimes that I didn't do. So they threw me in the hole,” he said. “I was totally psychotic. … I was terrified out of my mind.”

Months earlier, at 17, he had made the decision to move to Lincoln, Nebraska, after graduating from high school. He got an apartment, bought a car, paid rent, supported himself, worked 40 hours a week at the grocery store.

Then came a schizophrenia diagnosis.

"This was '74. We didn't know a lot about mental illness," Abraham said.

It's not that different from how we talk about mental illness in 2024, at least not according to Nancy Abraham, Dylan's mother. She's one of the founders of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and served as the founding president of NAMI Wisconsin.

She's also on the verge of 90, and has been pushing for the improved treatment of people with mental illness since she got the phone call from jail 50 years ago.

In the intervening decades, she and Dylan have seen a lot of good work being done. Nancy fought against a current that could have placed Dylan into long-term custodial treatment. And, just five years before his schizophrenia diagnosis, an innovative program, Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT), launched in Dane County that would give Dylan the tools he needed to live independently in the greater Madison community.

For the most part, Dylan has lived with minimal hospitalizations for his mental illness, a testament to his experience with dedicated treatment specialists. There have been six hospitalizations in his 50 years of schizophrenia, and much of that was the result of adjusting to strong medications like Haldol, lithium, Mellaril, Stelazine and Thorazine. (Some of these have since been discontinued for safety concerns.)

But people age.

At 68, Dylan now has entered the age bracket where physical health risks are heightened. He has dealt with cancer and kidney damage that required him to work with medical specialists who don't typically have adequate training in treating people with mental illness. It’s an issue especially on the mind of his mother, who has spent a lifetime watching over, and advocating for, her son.

“Society isn’t ready” to handle the wave of health care needs for older adults with serious mental illness, Nancy Abraham said, even as she has beaten the drum over and over again about the question of treatment accommodations.

“So my question is what is society going to do? When will society be ready? Where, why and how are they ready? And they’re not,” she said. “I’ve been asking this question for 20 years. It seems people don’t have the foresight.”

Residential centers wary of taking on people with mental illness

Of the 49.2 million adults over age 65 in the country, 1.4% to 4.8% have a serious mental illness, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Older adults also have some of the highest rates of suicide across any age group, accounting for nearly 18% of all suicide deaths in the nation.

At the statewide level, according to a 2021 report from NAMI Wisconsin, an estimated 5% of Wisconsin adults have a serious mental illness — roughly a quarter million adults.

At the same time, the number of psychiatrists and providers specializing in mental illness across the country is projected to shrink to 38,821 across the United States, to say nothing of the low interest in the field of geriatric psychiatry among newcomers.

In Wisconsin, around 3% of all physicians in psychiatry specialize in geriatrics, said Sarah Endicott, a clinical professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison focused on geriatrics.

As it stands, said Endicott, if existing geriatric psychiatrists took on all the older adult patients with serious mental illnesses, each would have around 20,000 patients. And, according to data from Wisconsin Hospital Association's psychiatric bed locator, only 46 available inpatient facility beds are available for geriatric psychiatric patients on average across the whole state as of May 2.

Compounding matters, Dr. Kenneth Robbins, a clinical psychiatrist at Agrace Hospice in Madison, said chances are high a patient with a serious mental illness requiring residential admission to a nursing home will be turned away.

"People are more careful about admitting you to their facility because they're worried you're going to create problems," Robbins said.

Even in a hospital, Dylan Abraham struggled to get appropriate care

Dylan Abraham got a preview of what could be in store for him after he suffered kidney damage in the middle of being treated for lymphoma.

Last August, he fell out of bed and "couldn't move an inch." He ended up stuck on the floor for 12 hours before his mother found him.

Abraham was so sick he couldn't move in his hospital bed, yet he felt pressured by one hospital specialist, who made it clear he didn't want to deal with Dylan.

“Every morning he’d come crashing through the door with, ‘Oh, you're going to be discharged today,” Dylan said.

He started hallucinating during the day and seeing visions in his sleep. He experienced that for four days, the worst it's been since before he entered PACT.

"He called me the next day and said, 'I think you better call (the doctor). Something's wrong,'" his mother said. "He was able to ascertain that his brain was not working right."

Somewhere along the way, the hospital had started cutting his Clozaril in half, the anti-psychotic medication used specifically to treat schizophrenia.

Nancy Abraham suspects the oversight had to do with inadequate training in serious mental illness treatment.

Today, she worries that the focus on mental illness has been usurped by mental health awareness campaigns, which don't sufficiently address serious mental illnesses. Destigmatizing mental health conditions are certainly important, Nancy Abraham said, but should not replace discussions that can advance education on mental illness.

Research backs that up. In a study focused on the competency of primary care general internists, many practitioners told researchers they felt comfortable treating common diagnoses like anxiety and depression through screenings and patient health questionnaires, but felt "out of their leagues" when it came to diagnosing and treating serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

"Many, many in the medical profession know very little about mental illness," Nancy Abraham said. "And just because a person knows something about mental health doesn't mean a person knows about mental illness exactly."

Dylan discovered other gaps in treatment during this hospital visit. He remembers the long wait at the hospital for an inpatient rehabilitation bed to open up following kidney treatment.

Eventually, he and his mother would learn that the hold-up had to do with the inpatient rehabilitation area “not feeling they’d be able to meet the needs of the individual,” Nancy Abraham said.

It wasn't just them. According to Mary Kay Battaglia, the executive director of NAMI Wisconsin, a majority of inpatient rehab facilities don’t accept clients with serious mental illness. Often, it has to do with “liability and capacity,” Battaglia said.

“Most inpatient physical therapy centers will not accept you with a diagnosis or a recent psychiatric admission,” Battaglia said. If you have mental illness, a physical ailment, “and you need inpatient physical therapy, too bad.”

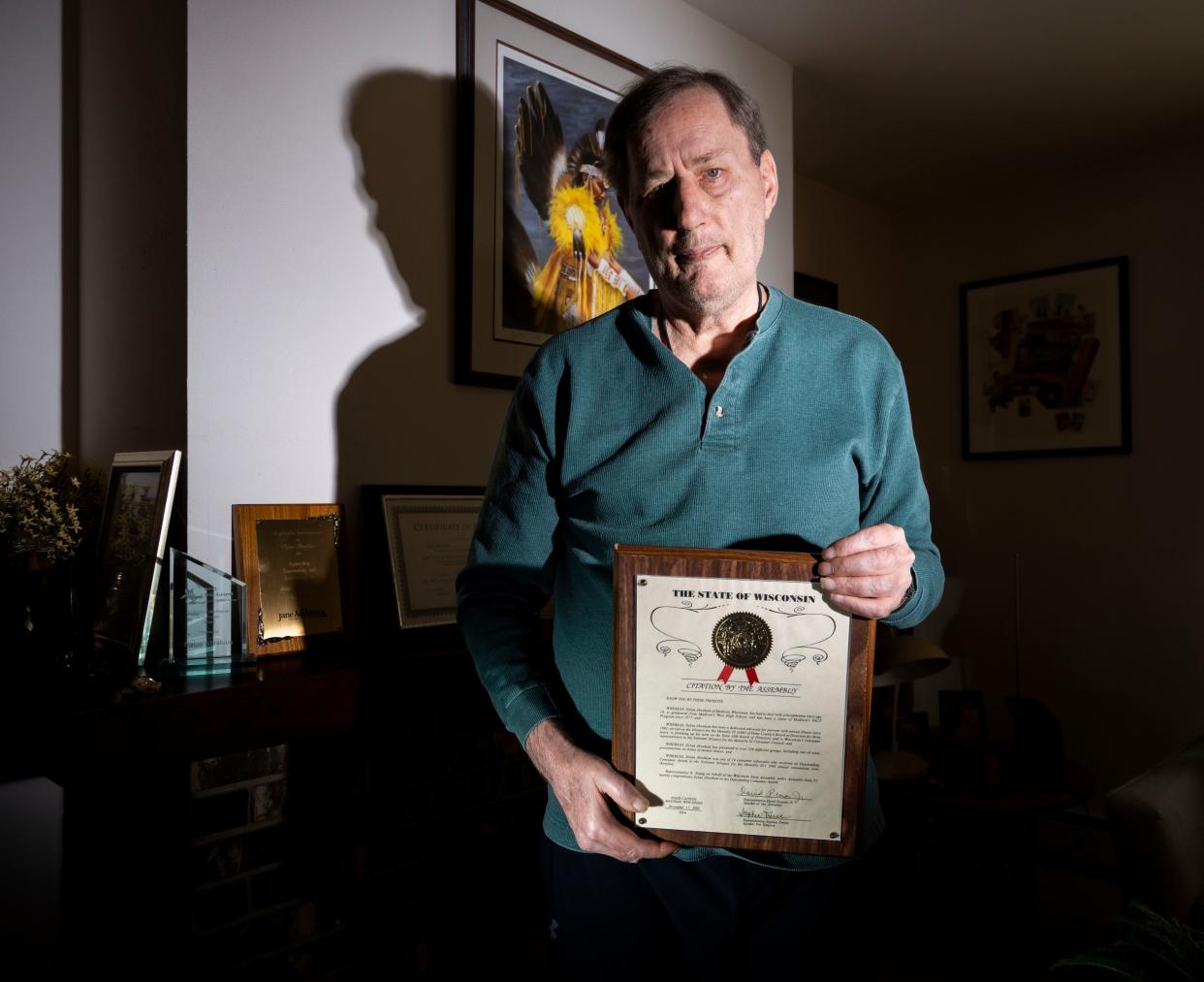

An life of advocacy, independence

It's been 41 years since Dylan was last hospitalized for schizophrenia, and he is quick to credit PACT — the Madison program that launched shortly before his diagnosis — for allowing him to move beyond his own community.

He went to London, he toured the United States, he set up individual meetings with 42 politicians in Wisconsin to talk about PACT, also known as the Dane County model.

"I became very politically involved, city-, state- and nationwide. The reason I got involved with politicians was to educate and work with them on persons with mental illness and educate them," he said.

In 1997, he returned to Lincoln, Nebraska, where he met up with his friend and his friend's brother, whom he'd once accused of stealing his keys and who, ultimately, called the police on him.

"That was a blessing to do that, because it was total closure, no grudges. They understood I was ill and I understood why they called the police," Dylan Abraham said.

He considers himself one of the lucky ones. He began his adulthood dealing with police mistreatment, systemic discrimination, stigma and five hospital admissions between 1974 and 1977. Since then, he’s been able to live a life of independence and advocacy.

He’s made speaking up about mental illness a lifelong career, taking part international speaking gigs where he confronts the stigma, the discrimination and the mistreatment he and millions of others around the world endure on a daily basis. He’s authored self-published books, several hundred articles and poems on the topic.

He comes home to a Middleton condo and, through PACT, knows how to identify and manage symptoms on the rare occasions they arise. He drives, and takes care of errands on his own.

Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter cited one his essays, "Getting Well Is Not a Race," in her book, "Helping Someone with Mental Illness."

"The brain is an organ of the body, like the heart or the liver or the kidney. I had a severe, life-threatening kidney incident, but it's treatable," he said. "People with mental illnesses aren't looney or crazy or out of their minds. They have diseases, treatable diseases."

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Mental illness in elderly gets little support in Wisconsin