Many local bilingual special ed kids are cheated by schools. Here’s how it happens

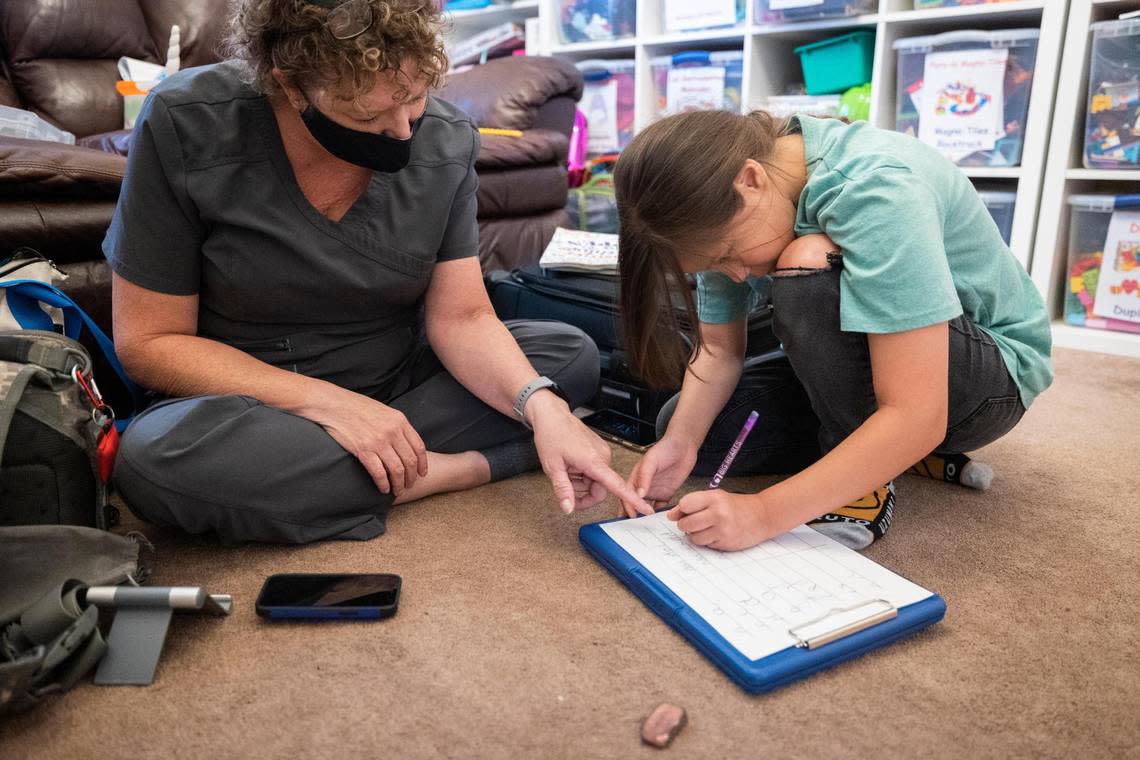

In the backdrop of Liz Piñón’s living room are a whiteboard, educational posters, a bookshelf and many more items labeled in English and Spanish. A dining table behind the couch comfortably seats Piñón’s 9-year-old triplets and their school teacher.

Piñón’s home has been converted into a classroom for two years, since the triplets’ pulmonologist gave the order to avoid unnecessary risk of exposure to COVID-19.

Santiago, Frida and Felícita each have cerebral palsy and ADHD. Felícita uses a wheelchair, Frida has sensory issues, and Santiago is on the autism spectrum and has a feeding tube. A Crowley school district teacher visits them four hours a week to provide special education services. The teacher guides them through an online program to help get them on grade level.

Since starting school in Crowley around five years ago, Frida, Santiago and Felícita have also been entitled to dual language services. Santiago recently tested out of the dual language program, meeting English proficiency requirements. But this past school year, Frida and Felícita didn’t receive any dual language or English as a second language services.

Santiago, Frida and Felícita grew up speaking Spanish at home and have improved their English with the help of bilingual teachers who have gradually introduced English over the years. Frida and Felícita still need regular dual language support, Piñón said.

When Piñón realized they weren’t receiving their dual language services this spring, she said, she felt horrible.

“I felt like a failure as a mom,” Piñón said. “How did I not realize or notice that my kids at home were not getting those services that they needed and deserved? But then why does it have to be a fight? Like I feel like every single day of my life, I’m fighting for services for my kids.”

Piñón’s situation isn’t unique, according to experts, parents and teachers interviewed by the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. They say emergent bilingual children, or students whose native language isn’t English, who also qualify for special education services have trouble accessing those services in a language they understand. Because of language barriers and cultural differences, students may not be evaluated for special education properly. And because of teacher shortages and a lack of resources in other languages, some parents are pushed to abandon language accommodations altogether.

But districts that fail these students are violating state law. The Texas Education Agency requires school districts to provide all appropriate linguistic and special education services to any student who qualifies for them.

Implicit biases

When Piñón first moved to Crowley around five years ago, she was told she had to choose between special education services in English or dual language services on their own. She was told special education services trumped bilingual services.

“I didn’t know better at that time,” Piñón said.

For the next several years, she said, her children got inconsistent dual language accommodations despite qualifying for them.

When Piñón realized this year that her children didn’t receive any dual language services, she filed a complaint with the Texas Education Agency and brought it to the attention of the school district. She said the district told her that her children’s dual language services were being met by their special education teacher, who is Latina. But the teacher wasn’t a certified bilingual or English as a second language teacher.

Email documents obtained by the Star-Telegram said that the district wanted to resolve the complaint “informally.” If Piñón withdrew her complaint from the Texas Education Agency, the district would provide 30 hours of tutoring to make up for the learning loss. Piñón said she reluctantly agreed to the informal resolution.

“They never apologized,” Piñón said.

The Crowley school district did not answer questions from the Star-Telegram about why Piñón’s children weren’t provided dual language or English as a second language services for the school year.

“Our educators work alongside families to ensure students receive the individualized instruction and related services they need to thrive,” a Crowley district spokesperson said in a prepared statement. “We pride ourselves on being responsive to and partnering with parents to address students’ needs, and Crowley ISD continues to provide training and support for staff to meet the needs of emergent bilingual students.”

Monica Santiago, special projects advocate and investigator at Disability Rights Texas, said Crowley is not the only district where she’s heard reports of inappropriate levels of dual language and special education services being provided for children. She said many factors can contribute to services not being provided in a student’s native language.

The committee charged with assessing language needs for each student, the Language Proficiency Assessment Committee, and the committee tasked with determining special education accommodations, the Admission Review and Dismissal Committee, are meant to work together for students who need both services, Santiago said. They can ensure that students are being instructed by a bilingual and special education teacher at the same time, that certain language-based services such as speech therapy are being provided in their native language or that a student has adequate time to receive both services from different sources.

“Sometimes that collaboration is not happening, or it’s not happening in an effective way,” Santiago said.

Parent involvement is also key in getting children the services they need, Santiago said. But sometimes Spanish-speaking or immigrant parents don’t find the school system accessible.

Undocumented parents may have fears about their status being uncovered, which can cause them to avoid lengthy conversations with the district, Santiago said. Some parents are only familiar with the education system in their native country, which can prevent them from actively participating here. Or sometimes school districts don’t provide appropriate materials in the parents’ native language.

If an evaluation for special ed isn’t done properly, there can be issues too, Santiago said.

“If an evaluator is not as experienced, they may just say it’s a language based issue, and chalk it up to that, rather than actively evaluating to identify whether a disability really exists,” Santiago said.

For a student to be helped properly, districts have to recognize all of the student’s needs, Santiago said.

“Not only am I a student who needs special education services, but I’m also a student who’s learning the English language. And sometimes the implicit biases that that student is going to experience are real,” Santiago said. “Sometimes an educator or professional’s inability to understand where those two needs intersect can affect their ability to really see what the true need of that student is.”

Ultimately, not providing language accommodations can make it harder for non-English speaking students to succeed, she said.

“You’re asking me to implement strategies to overcome the limitations that present themselves as a result of my disability, but you’re giving me those strategies in a language that I can’t understand,” Santiago said. “I don’t have the opportunity to have as much time to implement that strategy .... I would have had to take the time to learn the English language first.”

Santiago said districts should recruit qualified bilingual evaluators and ensure parents get the information they need in their native language.

‘It’s about equity’

Hjamil Martinez-Vazquez, a bilingual educator in the Crowley school district, said he’s long noticed a lack of services provided in Spanish for special education students. He said it’s unfair for students not to receive the services they’re entitled to.

“It’s about equity,” Martinez-Vazquez said.

He said he’s heard of cases where Crowley encourages parents of bilingual children to switch to general education classrooms because that’s where their special education services are provided. But the equitable approach, he said, is providing all of the services a child needs.

Martinez-Vazquez said Crowley should show a deeper commitment to these student’s and their families by encouraging bilingual teachers to get a special education certification and encouraging more collaboration between special education and bilingual teachers.

“It’s an issue of trying to understand how we actually address the special needs of every child,” Martinez-Vazquez said.

Marian Estes’ 5-year-old son, Jedidiah Estes, is on the Autism spectrum.

If there’s a change of routine or a sudden loud noise in his dual language class, Jedidiah usually cries and hides under his desk, which can be disruptive for his learning, Estes said.

“What helps him is [someone] talking to him and letting him know what will happen or offer to hold him or his hand, and he usually can get back to work,” Estes said.

Estes started the special education evaluation process for her son last September at a Crowley elementary school. The district did the evaluation in English, citing Jedidiah’s higher performance in English in August. But Estes said Jedidiah had shown greater improvement in Spanish since the start of the school year. Getting the district to also do a special education evaluation in Spanish took some convincing, said Estes, who is a dual language teacher for the district.

“Why would you test him in that language whenever you know that that’s not his instructional language? It’s not his home language. It’s not the language that he speaks,” Estes said.

The Spanish evaluation had to be contracted out in May, which took longer to arrange and conduct, Estes said. The district didn’t have a bilingual evaluator available.

Estes said that got her thinking.

“What if he does qualify for that service? ... Like where’s the Spanish speech pathologist? Where’s the Spanish special education service teacher? Where’s the Spanish diagnostician ...? Do we have any of those people?” Estes said.

A spokesperson for the Crowley school district said the district had three teachers certified in both bilingual and special education, but didn’t clarify their specific roles. Thirty of the Fort Worth Independent School District’s 90 special education evaluators are bilingual. Fort Worth has 221 teachers certified in both special education and ESL and 15 teachers certified in both bilingual and special education, said assistant superintendent Corey Golomb.

Crowley’s original recommendation was to remove Estes’ son from the bilingual program and place him in a class where he would get instruction in English from a special education teacher and a general education teacher at the same time. But Estes disagreed. She didn’t want him removed from the dual language program, and said his needs were behavioral rather than intellectual.

“Why would you take the skill that he’s doing the best in, and remove him from that environment and put him in a classroom with students that have an intellectual disability when in this whole report, you’re saying he does not have an intellectual disability?” Estes said.

Estes’ Admission Review and Dismissal Committee meeting was held in May, which confirmed an Autism diagnosis for Jedidiah and validated his behavioral needs. His individualized education plan lists that a non special education certified paraprofessional will provide support in his dual language classroom for an hour a day.

Dual language vs. special ed

Estes said she got a lot of resistance when she decided she wanted to continue dual language services. When she said she didn’t agree with the school district’s original recommendation, she was told she could always refuse special education services.

“I had about seven different calls from seven different people within the district explain the program to me again and tell me how that was the best fit,” Estes said.

Estes is “pushing back a lot more than most parents do because I understand that they are required by law to give them the accommodations that they think is best,” Estes said. “You’re not supposed to fit the student to the accommodation. The accommodation is to help the student.”

Estes said she knew to advocate for her son’s rights thanks to her experience as a dual language teacher.

“It might work with other parents to consistently talk to them and then [parents think], ‘Well, I guess they keep telling me this is what is the best for him, so it must be true.’”

Estes said she suspects the district pushes bilingual students who qualify for special education out of the dual language program to avoid the higher cost of outsourcing bilingual special education services.

“It has been able to maneuver its way to move the majority of bilingual students to a general ed population for those that do need these special services,” Estes said. “That is the most easy, cost efficient way to work around this exact problem.”

The Crowley school district did not answer questions about the expenses related to outsourcing special education services compared to providing them within the district.

Shortage of specialized teachers

Santiago, the special projects advocate and investigator at Disability Rights Texas, said she’s heard of other cases across Texas like Estes’ where districts encourage parents of special education students to opt out of dual language instruction.

Sometimes it can be more expensive to outsource special education services in a language other than English, she said, but that isn’t always the case.

Golomb, the Fort Worth ISD assistant superintendent, said the cost of contracting out bilingual and special education services is about the same as district employees when the cost of benefits for district employees is factored in.

Many Tarrant County districts interviewed by the Star-Telegram only outsource bilingual speech language pathologists, if they contract outside help at all.

Depending on a student’s particular needs, many dual language or ESL students who qualify for special education services remain in their dual language or ESL classrooms and receive special education services separately in English.

If that option isn’t possible, Santiago said, many districts might encourage parents to opt out of dual language services because it’s easier to provide special education services in English. There are already many designated classrooms and programs devoted to it. In many cases, putting a student in a bilingual or ESL special education classroom would require the creation of an entirely new program and hiring teachers that are hard to find.

Bilingual teachers have been understaffed for years, a strain only heightened by the pandemic, so finding a teacher certified in both bilingual and special education is like finding a unicorn, experts said.

Special education certified teachers are also in short supply, said Fort Worth school district’s chief academic officer, Marcey Sorensen. “We’re never going to have enough of that combination” of certified special education and bilingual staff members.

But Sorensen said the district continues to work to recruit more of these teachers, offering stipends or partnering with local universities.

Santiago said Texas lacks a combined special education and bilingual certification, making it harder to find teachers who meet both of the criteria.

Bilingual teachers are also not encouraged to seek out additional certifications in Crowley, Martinez-Vazquez, the bilingual educator, said. Most districts don’t continue providing the bilingual stipend, which can range up to $10,000, when bilingual teachers stop teaching in bilingual classrooms.

A recent push by lawmakers to establish a combined bilingual and special education certification could help with staffing struggles. The bill establishing the certification in Texas passed last year, and legislators are working toward implementation.

According to testimony from Texans Care for Children, a children’s policy agency in favor of the bill, the certification could help create a “streamlined process for districts to hire educators equipped to serve” bilingual and special education students.

The agency’s research found that students and their parents often had to choose between special education services and language services because of a lack of teachers equipped to provide both of those services.

“I think it’s really important that we do” establish a certification, said state Sen. Beverly Powell, a Democrat from Burleson. “But we have to have the people in the system to be able to do it ... and right now that’s really complicated to do.”

Powell said the problems can be attributed to the struggle in recruiting and retaining teachers in general. She said teachers aren’t being compensated enough, and many left the profession during the pandemic.

A legislative committee tasked with implementing the certification will likely be formed by August, with recommendations for the next legislative session in December, Powell said.

A child’s full potential

Like Estes, Piñón, the mother of triplets, said she feels like she’s constantly fighting for services for her children.

“It’s hard,” she said. “A lot of our parents by the time they’re in fourth or fifth were exhausted from fighting the district. We’re just tired. We’re spent.”

But Piñón said she keeps pushing to give her children the best possible education.

“Because they’re brown, because they’re disabled, because they’re technically under Medicaid … we know, statistically, what happens to kids like these,” she said. “We work twice as hard so that we make sure that they get the best of everything.”

Piñón hires occupational therapists, physical therapists and speech therapists to visit the house regularly. They also see a neurologist who has cerebral palsy, so her kids can see what’s possible.

Piñón said she hopes she’ll get extra services from the district for not providing dual language services for the full year. She hopes they’ll get the additional tutoring to make up for lost time and the district will develop an action plan to get her kids on grade level.

“My kids have special needs, but none of that should stop them from reaching their full potential,” Piñón said.