‘Man Mountain’ Dean, Ed ‘Strangler’ Lewis, drew early pro wrestling fans in Fort Worth

As someone who went to “Live Main Event Wrestling” at the North Side Coliseum on Saturday nights, I have fond regard for pro wrestling, fake as it may be. I and a high school buddy loved seeing stars like Fritz von Erich, Billy “Red” Lyons, and Cowboy Bob Ellis toss each other around the ring.

My sister’s boyfriend at the time was a KTVT camera man, so we got to sit up in the broadcast booth with the announcers.

Until the 1920s, wrestling was a niche sport confined to college and the Olympics. When it began to catch on with the public it attracted the same blue-collar, urban audience as professional boxing. The difference was that pro wrestling was contrived. The wrestlers were performers first, athletes second.

Pro wrestling really took off in Fort Worth after KTVT picked it up to help fill its lightweight schedule. The bouts had no rules except to put on a good show.

A ready-made TV audience was primed for pro wrestling by the live “shows” put on by impresarios starting in the late 1920s. The American Legion sponsored bouts at an open-air arena on North Main. In 1931, the weekly “wrestling shows” moved into the North Side Coliseum, which was otherwise empty much of the time. Seats were cheap (“two bits”) and weather was not a concern indoors.

Folding chairs for roughly 1,000 fans were set up on the coliseum floor, and every seat was filled when stars like Ed “Strangler” Lewis came to town. For several years he was the undisputed heavyweight champion of the ring.

This was no-holds-barred brawling that might start in the ring but didn’t always stay there. The contestants were big bruisers with colorful stage names and signature holds.

A columnist for the Fort Worth Record-Telegram, said the matches “contain elements of the prize ring ... and the lower elements of a free-for-all fight.” He described one bout this way: “The two participants went in for everything but shotguns, dirks and brass knuckles. One even bit the other one!”

Fort Worth’s first wrestling promoter of record was Roy Terry, who in 1929 began renting the City Recreation Building on Vickery for a full evening of bouts. Two of his headliners were Sailor Jack Woods and Cyclone Fox. To keep the audience in their seats between bouts Terry offered singing acts and soft-shoe dancers.

Cyclone Fox’s real name was Leon D. Fox, who had a day job with the Dallas Fire Department. His brother, George A. “Jack” Fox, was also a professional wrestler who held the welterweight title in several states before retiring to the business side.

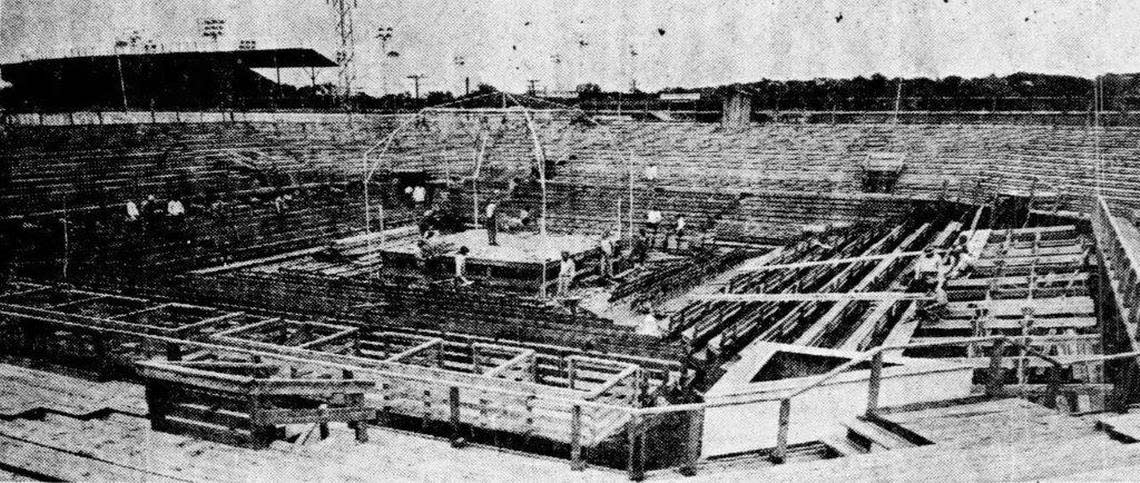

Jack Fox became an impresario who partnered up with Clifford E. “Crannie” Cranford in 1930 to promote matches at the North Side Coliseum and the old Klan Hall on North Main. They did that until they could build their own outdoor arena at North Calhoun and Sixth, a spacious venue that could accommodate more fans than either the North Side Coliseum or City Recreation Building. They opened their sunken, open-air arena in 1932 at a cost of $8,000. It had seating for 7,500 fans, including “box seats” in the upper section.

The future of the “mat game” in Fort Worth looked bright until Jack Fox was killed along with his pilot in a plane crash near Cisco, Texas, on June 6, 1932. This was less than a month after the new arena opened. Wrestling fans were stunned. Fox’s death left his widow as partner to Clifford Cranford.

Within a year, Leon “Cyclone” Fox bought out Cranford, going into business with his sister-in-law as a silent partner under the corporate name Fox & Fox. He moved from Dallas to Fort Worth to run the company as president. He told the Star-Telegram, “I’m going to give Fort Worth fans the best wrestling possible.”

In 1936, Fox & Fox moved their matches back indoors to the North Main Auditorium (formerly Klan Hall), under the name Fox & Fox Wrestling Emporium. They put on entertaining programs at “popular prices” and brought in big names, like 340-pound Man Mountain Dean, a recent “sensation” wrestling at Madison Square Garden. They also introduced fans to young up-and-comers, few of whom would go on to fame or fortune, even if they had a signature move, like Billy Edwards’ “chiropractic headlock.”

Promoters had to come up with an endless array of gimmicks to fill seats, like hiring former heavyweight boxing champ Max Baer as a referee or promising the “Masked Marvel” would unmask if he were defeated. Leon “Cyclone” Fox split his time between the office and the ring until 1933 when he announced his retirement. It did not last long; he returned to the ring as a fan favorite with his signature “octopus hold.”

Though a lot of the rivalries were arranged, occasionally a real donnybrook erupted. In June 1934, Cyclone Fox fell out with the Bothwell-Kane American Legion post on the same night they were sponsoring the program. Fox settled the argument by tossing the Post’s representative, Leon Parkman, out of the ring by force. Real or staged? The Tarrant County district attorney investigated but filed no charges, and neither of the principals were talking.

In 1938 Fox & Fox shut down, taking the city’s biggest promoter off the board. Pro wrestling was about to go under locally until July 1941 when a couple of Dallas promoters rode to the rescue. They put together a heavyweight card of familiar names for a return to the ring at outdoor Rockwood Park. The following year KRLD radio began broadcasting the bouts, and in the mid-1950s, professional wrestling broke through to television, returning to the North Side Coliseum two nights a week.

Pro wrestling embraced a kind of diversity at a time when other “sports” were strictly segregated. In the 1930s, there was Al Karasick, the “Russian Lion;” Abe Coleman (the “Jewish Light-heavy” champ); Jules Strongbow (Native American), Tommy O’Toole, Speedy Gonzales, and Frenchy LaRue, each representing a different nationality. The 1960s gave us Duke Keomuka, believed to be Japanese. Furthermore, the script was never set in concrete. If a bad guy became popular with fans, he could be transformed into a good guy. That’s what happened to Fritz von Erich in the 1960s.

Professional wrestling also offered a second career to athletes retired from other sports but not ready for the rocking chair. Men like Ernie Ladd, Bronco Nagurski, and Fort Worth’s own Sully Montgomery all went from professional football to the ring. And Sully Montgomery didn’t stop there. He went from the ring to being elected Tarrant County sheriff four times (1947-1953). You have to wonder, how many of Montgomery’s wrestling fans went on to cast a vote for him in a sheriff’s election?

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.