Should magistrates oversee contested divorce cases? Why Common Cause RI is objecting.

PROVIDENCE – Family Court Chief Judge Michael B. Forte wants magistrates to perform the same duties as judges and preside over and decide contested divorce cases, some of the most emotionally draining matters the court hears.

But Common Cause Rhode Island argues that if magistrates are going to perform the same role as judges, they should be subject to the same selection process and be vetted by the Judicial Nominating Commission.

“If Family Court magistrates are allowed to conduct trials, they should be chosen in the same manner that Family Court judges are selected – through the Merit Selection process. The Court cannot have it both ways – arguing that magistrates should be selected in a different manner from judges but granting those magistrates the same powers as judges,” John Marion, executive director of the good-government group, wrote to the House Committee on the Judiciary.

State lawmakers weigh identical bills

At Forte’s request, identical bills were submitted in the state House and Senate that would empower the chief judge to assign Family Court magistrates to hear contested divorces.

“As you might expect, contested cases take much longer to resolve. … I believe that the more judicial officers who hear these cases, the more likely the cases will be settled short of a lengthy trial,” Forte wrote to the House Judiciary on Thursday.

The legislation was submitted on Jan. 24, the very day the state Supreme Court issued a ruling in which it declined to take up a legal challenge questioning a Family Court magistrate’s authority to decide a contested divorce case.

More: Who watches to make sure RI judges act ethically? A look at the panel veiled in secrecy

“I maintained that Magistrates, unlike the life tenured Chief Judge and Associate Justices of the Family Court, did not have the statutory authority to hear contested divorce cases,” said Michael J. Lepizzera Jr., who represented the ex-wife in the case.

The high court concluded that the magistrate issue was not preserved and was, therefore, waived on appeal. The ruling upheld a decision by General Magistrate Daniel V. Ballirano.

In writing to state lawmakers, Forte asserted that only one litigant had questioned the general magistrate’s authority over contested divorces in the 35 years that they had heard and decided such cases.

“Our position has consistently been that the statute provides the Chief Judge with the authority to assign any of the Magistrates to any calendar that will assist the Court in fulfilling its mission,” Forte said.

What's the difference between judges and magistrates?

Family Court currently has 11 magistrates and 12 judges. Under state law, magistrates are selected by the chief judge of the court with the advice and consent of the state Senate. They sit for 10-year terms that can be renewed.

State law empowers magistrates to hear juvenile justice and child custody matters, such as temporary placement, custody and adoption, as well as to enter divorce decrees.

More: A Woonsocket man was declared incompetent. It took advocates months to get him out of the hospital.

Under the legislation, Forte could authorize magistrates to hear contested divorce petitions as well.

The salary range for the Family Court magistrates is $176,503 to $211,803, according to Lexi Kriss, spokeswoman for the courts. Forte’s most recent magistrate picks were made with the assistance of a Family Court Magistrate Selection Committee.

Judges, meanwhile, go through an interview and public hearing process before the Judicial Nominating Commission, which then forwards three to five candidates’ names to the governor as possible nominees for the lifetime posts.

The lifetime Family Court judgeship comes with a salary range of $188,249 to $225,897, Kriss said.

Speaker K. Joseph Shekarchi said through a spokesman that Forte indicated there would be no increases in salaries or benefits for the magistrates for the increased duties.

The passage of the legislation also would not require the appointment of additional Family Court magistrates, according to Forte.

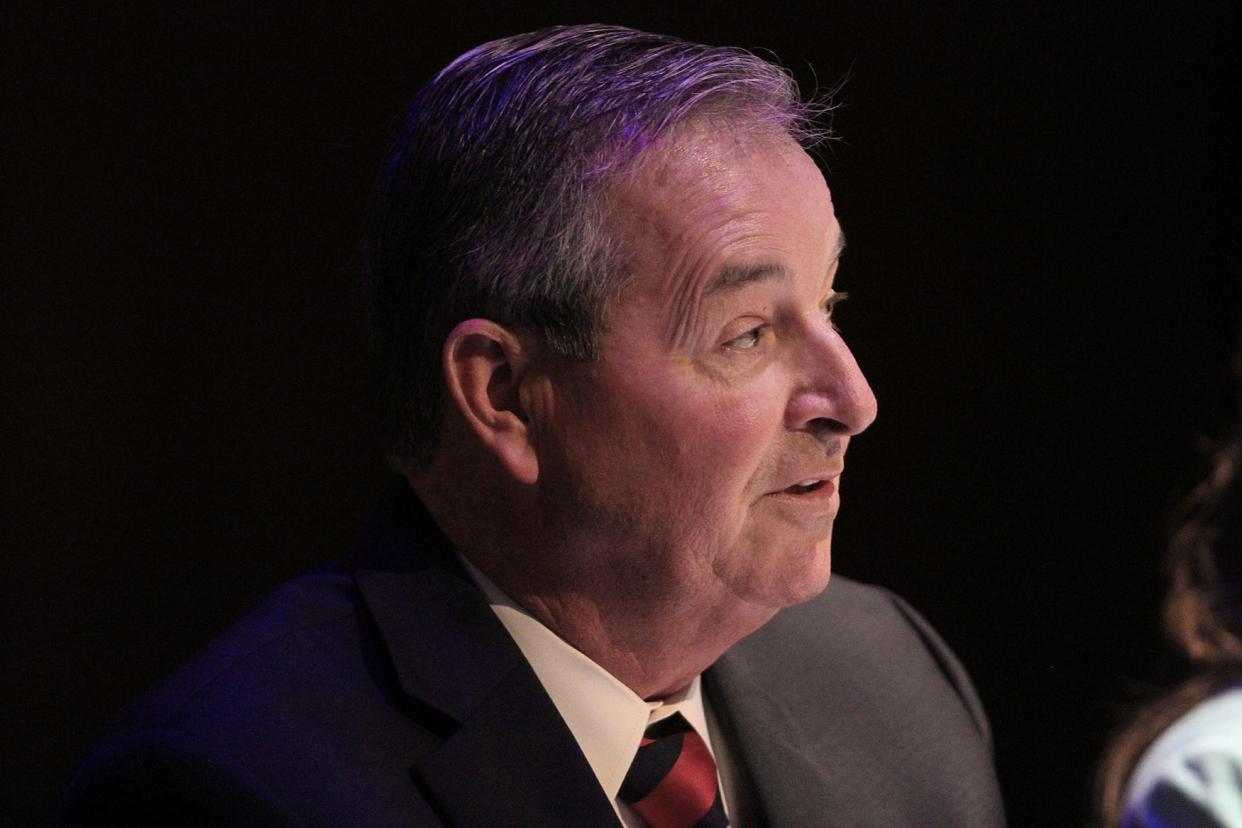

House Judiciary Chairman Robert E. Craven Sr., who sponsored the legislation on the House side, noted at a hearing Thursday that magistrates are not in the same pension system as judges and are, in essence, state workers.

Magistrate posts as 'loopholes'

Magistrate positions are often viewed as a steppingstone to a lifetime judgeship and an end run around the merit selection process for judges approved by Rhode Island voters in 1994 after a series of scandals.

According to Marion, state lawmakers began exploiting the magistrate loophole almost immediately, with numbers ballooning from a mere handful performing administrative functions to dozens.

“Supporters of the Merit Selection system, including Common Cause Rhode Island, pointed out that magistrates are judges in all but name and therefore should be subject to the same selection process as all other judges,” Marion said, continuing, “Yet supporters were told time and again that magistrates are not judges because they do not conduct trials. …. This is a practice that the Family Court has already engaged in and was subject to recent litigation and is only now seeking statutory authorization for.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Bills would let RI magistrates oversee contested divorce cases