A look behind WSU president’s vision for a health science center: ‘This can be done’

What does a 1970s Houston choir teacher have to do with the $300 million health science center proposed for downtown Wichita?

Quite a bit, as it turns out.

Wichita State University President Rick Muma was in eighth grade, sitting in choir class in the Houston public schools, when his teacher announced he would be leaving to become a physician assistant — a relatively new career at that time.

Muma went on to become a PA himself. He eventually earned a master’s degree in public health from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston — located at the Texas Medical Center, which serves as a kind of a model for the proposed center he’s championing here.

The Texas Medical Center is home to more than two square miles of medical institutions that often work together, including the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas A&M School of Medicine. Muma called it a “really enriching medical environment” where such things as open heart surgery and the heart bypass procedure were pioneered.

Muma, who was born in Wichita, saw a need for something similar here when he returned in 1994 as a WSU faculty member.

“I was a little bit in shock about just kind of the lack of coordinated care in the city . . . like you see at a health science center. . . . I’ve always thought that well, why aren’t we working more closely together, why aren’t we combining our efforts together not only in classrooms, but simulation spaces and just the way that we educate individuals in clinical settings?”

Muma said life in general and healthcare issues in specific are too complicated to be handled by one discipline or in one way only.

“It’s been proven in numerous ways and research that interprofessional training, when you have the whole team at your disposal and learning to gather around patient care, or a patient, that improves patient outcomes.”

The pandemic’s influence

About four years ago, when Muma was provost, he began having conversations at WSU about more integrated learning and also with the University of Kansas Medical Center about collaborating with the KU School of Medicine-Wichita, which had been having its own discussions about a new Wichita facility for itself.

Talks continued and included WSU Tech as well. Then the pandemic happened.

“And, of course, COVID made us think about how we should do all kinds of different things, not just in healthcare, but a number of things,” Muma said.

He was proud of how WSU’s Medical Laboratory Sciences department set up a molecular diagnostic laboratory for COVID-19 testing in just a few months. However, he wondered what could have happened if WSU already had a partner like KU.

“You just think if we were all together how we could have probably better responded to health care needs during the pandemic.”

Along with new ways of thinking came new public money through the American Rescue Plan Act, or ARPA.

Muma said one of the purposes of the money is “how can you come out of this post-COVID environment in a way that’s going to be beneficial to the community?”

He said WSU and KU approached the Legislature about accessing ARPA funds, “And so they gave us $35 million towards this project to help kick it off.”

Hard work still to come

WSU and KU also have a $60 million request to Strengthening People and Revitalizing Kansas, a statewide group that distributes ARPA funds. The schools also have requests to the Legislature for $10 million each to bond the expected $300 million for the center. The bond is similar to a mortgage.

“We still have to go through the hard work of creating more efficiencies and identifying space that can be shared and leveraged that way, which will help it become a little smaller, likely,” Muma said.

The plan is for WSU to move to the center its physician assistant and physical therapy programs, its school of nursing, its communication sciences and disorders program, its public health sciences program, its medical laboratory sciences program and possibly its dental hygiene program.

KU would move its schools of medicine and pharmacy to the center along with four clinics.

For WSU Tech, the move could include its programs for certified nurse aides, certified medication aides, home health aides, practical nurses, emergency medical technicians, registered nurses, patient care technicians, surgical technology and healthcare administration and management.

Comcare of Sedgwick County, the county’s outpatient mental health facility, could be part of the center at some point.

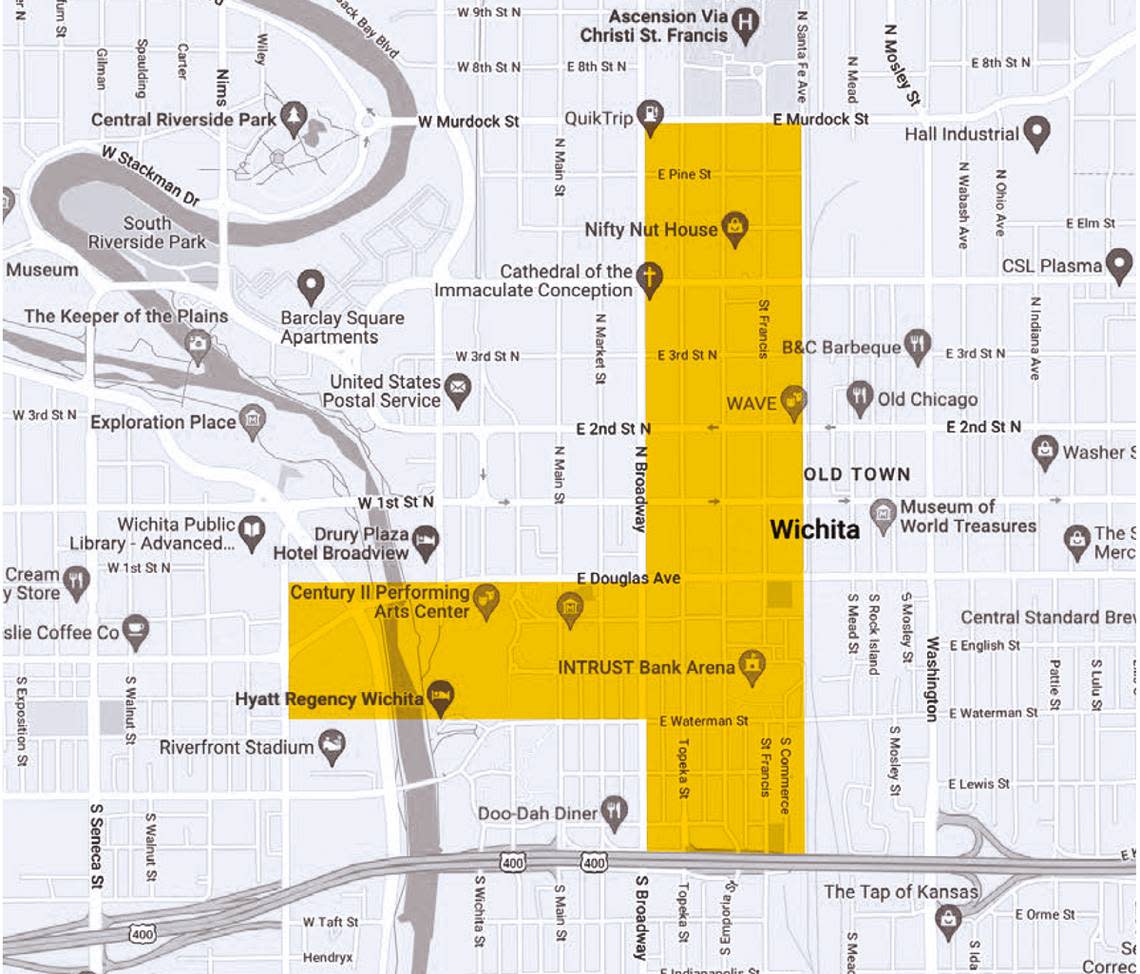

Although no site has been chosen, the center most likely would locate downtown — possibly around the area near William and Topeka, where Wichita Transit is leaving for its new home in Delano.

“If you go and study any of these kinds of facilities, they’re in the core of the city,” Muma said.

“It’s got good access to Kellogg . . . and of course Douglas. It’s centrally located. There’s an infrastructure that’s developing down there, there’s housing down there, there’s the entities that will be helpful to support students once they’re down there.”

It’s also adjacent to WSU Tech’s culinary school and the Kansas College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Muma said discussion of the science center started before the osteopathic school was conceived, but he said he’s been in regular talks with the school, and he said he could envision it one day having a role at the science center as well.

“It’s great that they’re there,” Muma said. “This is the beginnings of a true comprehensive health science center. And that’s how you solve problems — when you bring people together. You don’t do it on your own.”

‘Incredibly transformative’

Though Muma has firsthand knowledge of health science centers in Houston and St. Louis, he’s been studying the Phoenix Bioscience Core because it’s a more recent development. He’s visited twice, once with a legislative contingent and Robert Simari, executive vice chancellor for the KU Medical Center.

Bioscience executive director David Krietor was impressed with two high-level administrators “doing this together, exploring this opportunity, asking questions about what worked and what didn’t work.” He was even struck that they always sat next to one another.

“I wanted to take a picture and send it to our folks.”

What eventually became the Bioscience Core started with a 2004 push to get Phoenix’s first medical school. A health science center — where the University of Arizona, Arizona State University and Northern Arizona University each have a presence — came later.

Krietor said Muma and Simari had a lot of technical questions, such as accounting for cost sharing — what entity pays what percentage of basic things such as building security, landscaping and shared faculty.

He said that investigation is “the best thing that they’re doing and the thing that probably we should have spent a little more time on in the beginning.”

From 1992 to 1997, Krietor was economic development director for the city of Phoenix, “one of the most suburban of places.”

He worried about never achieving a viable downtown but said the Bioscience Core has changed that through attracting young people to work and study there, and new dining, music and sports opportunities have developed as a result.

“It’s very cool here,” Krietor said. “Things that I never really thought would happen are taking off.”

Greater Wichita Partnership president Jeff Fluhr sees the same potential for Wichita’s core.

“This could be the largest investment in downtown’s history, and that’s remarkable, because where does that go next?”

Fluhr called the health science center an “incredibly transformative project” not only for the city’s core but for the region and state as well.

In addition to bringing another 1,600 jobs downtown plus 200 faculty and staff and 3,000 students, Fluhr said the center “is a huge indicator to people beyond our region to how we work together to see great things come to fruition.”

Innovation Campus leads the way

WSU and KU hope to secure funding for the health science center this year, design it in 2023, start construction in 2024 and finish by 2026, which is when some of the ARPA money needs to be used by.

Muma is confident both in the partnership with KU and his own school’s ability to make the center happen.

“One of the things that I think helps all this is what we’ve done on (the) Innovation Campus,” he said of the 130 acres where 50 partners, including businesses, organizations and restaurants, have located.

“The university obviously has gone through a lot of transformation over the last 10 years, and has, I think, proven to this community that we can put things together in pretty short order.”

Muma already is thinking ahead to future phases of the center that include more research and testing.

“Obviously, bringing these disciplines together and universities together is likely to create more grant funding and . . . research labs and space. I think there’s opportunities for other institutions in the state to bring their own aspect to this, too.”

In one future scenario Muma envisions, that could include out-of-state institutions as well.

To start, though, Muma said “it just requires a lot of coordination and a lot of people giving up some of the way they do things to accommodate the other side. So that’s going to be difficult. There’s just no way around that.”

He knows others question whether the center will become a reality.

That negativity “distracts from really what we’re trying to do here, but I know from just being around the country and visiting universities that this has been done (a) long time ago, in lots of other places, cities our size, bigger or smaller.

“This can be done.”