Longtime NPR host meets ‘Best Strangers in the World,’ our latest book club selection

Ari Shapiro knows that journalists value objectivity, the so-called “view from nowhere.” And yet he contends that identity still informs everything a journalist does.

The longtime co-host of National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered” adds the caveat that he’s never taken a journalism class — a little levity from a man who spent five years as NPR’s justice correspondent during the George W. Bush administration and four years as the White House correspondent while Barack Obama was in office.

“Getting the facts right and being thorough and nuanced and fair and expansive and accurate is all incredibly important. Also, the view from nowhere was never really from nowhere,” Shapiro says. “It was from the perspective of the majority.”

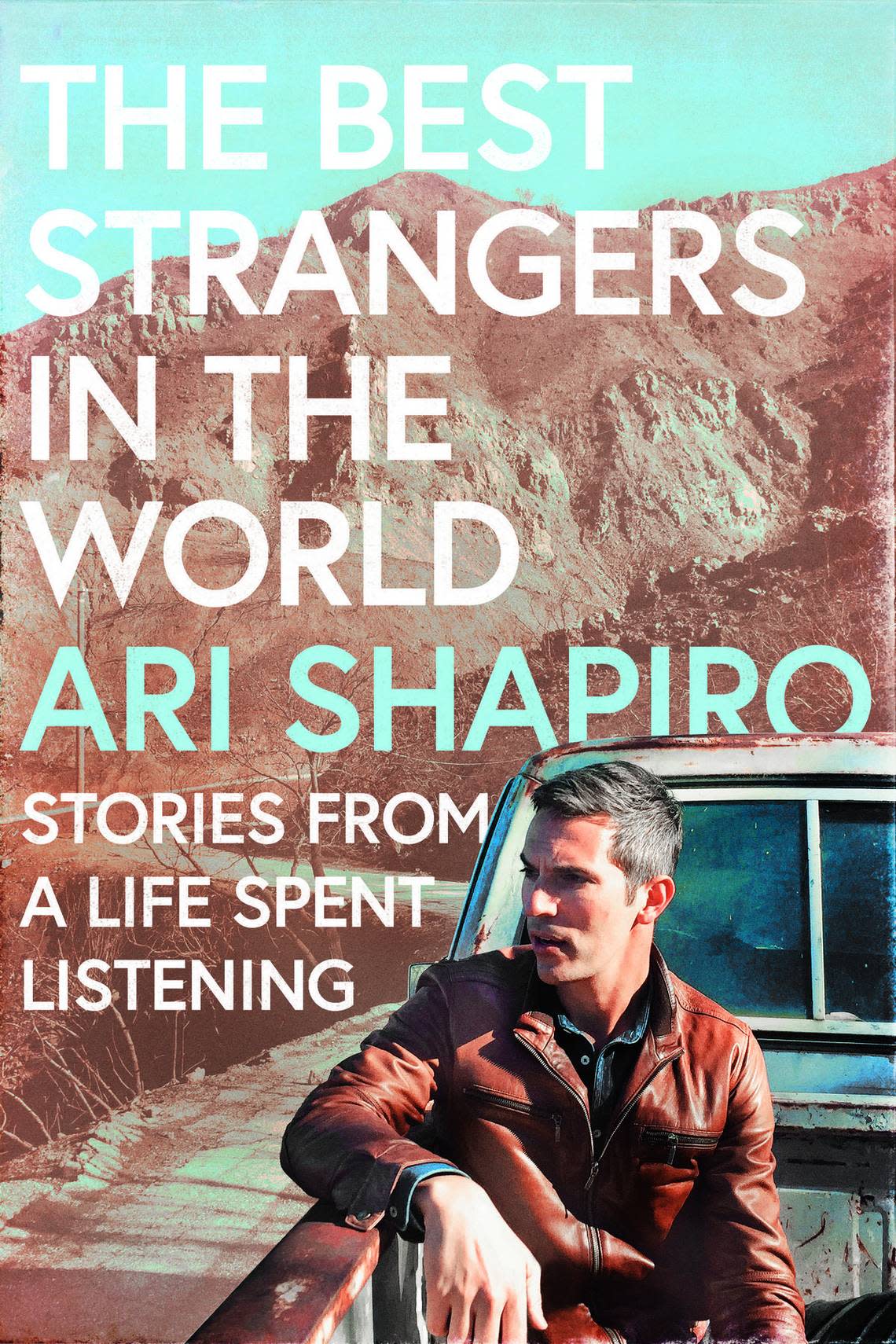

In “The Best Strangers in the World” (HarperOne, $28.99), his first book and spring’s FYI Book Club pick, he turns around and around the idea of how a person’s identity influences the choices he makes and therefore influences the world around him.

“It’s all well and good for me to pretend that the stories I tell from that war zone are completely free of personal perspective, but I don’t know that that’s ever actually true,” he says.

While he does spend some pages considering biases that may subconsciously influence his reporting, he dedicates more space to the flip side: deliberate choices that he makes as a unique individual.

Something he calls leaving his fingerprints.

For instance, he writes that his task for NPR in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks was to write brief remembrances of some of the victims.

His research led him to a family of three — a gay couple and their adopted 3-year-old son — who died when their plane hit the second World Trade Center tower. Shapiro, who is gay, highlighted them, thinking about the importance of using the word family for that relationship in 2001, when public examples were less common.

Someone else might have chosen other people, but “when I heard the segment on the air, I felt like I had left a small fingerprint on the record of the day,” he writes in the book.

He was reaching from his bubble into his listeners’ bubbles — a word he uses repeatedly in the book.

“I can see now that, as the self-reinforcing bubbles we live in become more impenetrable, I keep seeking out ways to help people listen to one another,” he writes.

And his radio work isn’t the only way he does that; he also tours and records as a singer with Pink Martini, a band from Portland, Oregon, where Shapiro grew up. He’s a musical diplomat with this group he describes as a “little orchestra. … worldly, glamorous and bubbly. Just campy enough without being silly.”

Though the members of the band aren’t necessarily polyglots, their repertoire engenders inclusivity by incorporating songs in more than a dozen languages. Shapiro has performed in red and blue states and in various political climates the world over and gets the same response everywhere.

“It’s a very different kind of connection from what you get hearing a story on the radio that hits you emotionally and personally,” he says. “But it is another form of powerful connection and creation of empathy and helping us relate to the people around us.”

At bottom, Shapiro’s most lasting fingerprint is on his ability to tamp down biases in others. And though his career has unfolded on a grand scale touching millions of people weekly, he suggests he’s really just doing his part.

He thinks about how his work might be similar to what he included in the book — in particular, a Zimbabwean woman fighting her government by planting flowers. He cites an interview he did in November with Naomi Alderman, author of the apocalyptic novel “The Future.”

Shapiro asked her how she faces the problems confronting humanity every day.

“She quoted a line from the ‘Talmud,’ the Jewish sacred text,” recalls Shapiro, who is also Jewish. It “says: It is not up to you to complete the work, but neither are you free to refrain from it.”

That is, he explains, if Savanna Madamombe in Zimbabwe can take subversive measures against the dictatorial regime of Robert Mugabe — measures that involve gardening — then “I can do that in whatever challenging situation I might someday find myself in. And so can literally everyone else.”

This is where the “best strangers in the world” come in. The title words are from a piece of art hanging in Shapiro’s bathroom.

The book looks back at people he’s met since he began reporting for NPR as an intern in 2001, many in situations of hardship or adversity who still manage to perform great acts of kindness and humanity.

Being neighborly. Being the best strangers. Leaving their fingerprints.

When challenges arise, he says, people might ask: “What am I going to do with that situation? And how am I going to respond to it?

“Some of those answers are going to be really interesting and dynamic and bring things out of people that you might not have seen if they hadn’t faced those challenges with that question.”

His interviews have included the wealthy, the powerful and the immensely talented, but have also included refugees, grassroots activists and fighters of all kinds.

And all of those people have to choose whether they act on subconscious biases or make conscious decisions based on sorting out something about themselves.

And if they, particularly those with limited power and influence, meet the challenges with optimism and the intention of changing things for the better, he says, “then those of us with more power and more of a voice and more of a platform have no right to throw up our hands and say it’s hopeless, everything is too hard, I give up.”

Anne Kniggendorf is a writer and editor for the Kansas City Public Library and is the author of “Secret Kansas City” and “Kansas City Scavenger.” Follow her @AnneKniggendorf.

Join the club

The Kansas City Star partners with the Kansas City Public Library to present a book-of-the-moment selection. We invite the community to read along. Kaite Mediatore Stover, the library’s director of readers’ services, will lead a discussion of Ari Shapiro’s “The Best Strangers in the World,” at 6 p.m. May 23 at KCUR-89.3, 4825 Troost Ave., Suite 202. Email Stover at kaitestover@kclibrary.org to join in or to learn about other discussion dates.

Shapiro will speak at 7 p.m. June 13 at the Central Library, 14 W. 10th St., as the third in the library’s four-part 150th anniversary speaker series. Free with RSVP.

An excerpt

Nathan told me that the other bartender, Bobby, still worked at Pulse. He wasn’t there the night of the shooting. Any pretense of journalistic distance popped like a soap bubble. I sighed to Nathan, “A gay bar is so much more than just a place to get a drink.”

“Right. It’s a home. It’s a family. It really is a place for us to connect and feel safe,” he said. “I couldn’t tell you how many stories I’ve seen of people who have walked through the doors as their first gay bar they’ve ever been to, and really felt welcomed.”

The gay rights pioneer Harry Hay used to talk about “Subject-Subject relationships.” He argued that society raises straight people to think about relationships as Subject-Object. The pursuer and the pursued; the conqueror and the conquest.

Journalism often feels that way. I arrive in a community and gather up stories from people who live there. Their voices become ingredients in a recipe that I mix, bake, and serve to an audience of strangers. Then I drift off like some Mary Poppins who hasn’t actually improved anybody’s life before floating away on her parasol.

Hay believed that one reason gay people exist is to demonstrate a different way of relating to one another. Not in service of a selfish goal, but in mutuality and recognition of one another as more than a means to an end. Not Subject-Object, but Subject-Subject.