The Long, Strange Story of How Indiana Jones Got His Hat

Pick your moment: That opening shot against the jungle-mountain skyline of the Peruvian jungle. The shadow thrown up the wall of a Nepalese drinking den. The figure stark against a burning Egyptian sunset.

The silhouette in all these scenes—all from 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, the movie that introduced Indiana Jones as anti-hero par excellence—belongs to Harrison Ford. But the star, indisputably, is his hat.

The felt fedora had long been movie costume currency amongst gangsters, gumshoes, and government heavies. But this one somehow made its character’s silhouette as reflexive as Darth Vader or Batman. It’s near-mythic qualities have been picked over by fans for decades.

But however iconic, Indiana Jones’s look was actually the unearthing of an archetype. An early cipher to the character can be found on a page torn from a 1976 edition of Lone Star Fictioneer, depicting a gunfighter called Francis Xavier Gordon, in a desert scene drawn by Jim Steranko. On it, Indiana Jones’s creator George Lucas had scribbled: "Bullwhip instead of gun," "Nazi truck and tank" to substitute a Bedouin camp—and, in place of the pith helmet Gordon clutches, "felt hat similar to H. Bogart in Treasures of Sierra Madre."

In that 1948 movie, Humphrey Bogart’s tattered lid reflects its wearer Fred Dobbs, a down-on-his-luck American treasure hunter on the downslope of a lust for gold. But it was Charlton Heston, in 1954’s Secret of the Incas, that was the true prototype for Dr. Jones— his Harry Steele not only sporting a deftly-angled fedora but a leather jacket and chiseled stubble, navigating a plot juggling romance, treasure hunting and double-crossing. Lucas’s love of pacey 1940s Republic serials blended these aesthetics with Nazis hunting mystical artifacts.

Lucas commissioned Steranko to visualise this in a series of 1979 artworks that would squarely nail the vibe of Indiana Jones—right down to the hat. With Steven Spielberg signed on to direct, now he needed someone to make it real.

"I never saw Jim Steranko’s drawings,” says Deborah Nadoolman Landis, whom Spielberg signed on as costume designer. “In the screening room with Steven, we sat alone and watched China and Secret of the Incas. He said, ‘that’s it—that’s the costume.’ [Basically] here’s Harry Steele, he’s now Indiana Jones. Bring him to life.”

Six weeks before shooting, and parachuted with her leading man into London where production was based, Landis and Harrison Ford set about crafting the character. “I aspire to designing from the inside out. We’re designing the man,” Landis says. “It’s a question of texture and creating a personality. And that is not a decorative pursuit. One of the reasons Indiana Jones has endured is because he’s not a cartoon. He took on Harrison’s native traits.”

And whatever sat on his head needed to reflect that. At the costume department’s basecamp at Camden’s Berman’s & Nathan’s with Ford in tow, Landis went back to the drawing board.

“This is how you find a hat for an actor, always,” says Landis. “You would stand in the fitting room, as Harrison and I did, and boxes and boxes of fedoras will be dumped on the floor. Or Panama hats. Or straw boaters. Because everyone has a different shaped head. And it is almost impossible to find a hat that suits you.”

Hats went on, hats went off. “Harrison has a long narrow face. We came across one that kind of looked OK. So I said, we’re going to lower the crown, and we’re going to shorten up the brim so you don’t have to wear it on the back of your head.”

Seeking a hatters of suitable esteem to make the final product, Landis eschewed iconic milliners Lock & Co, instead walking into Herbert Johnson. Not seeing an equivalent and wanting a wide brim to start from, she spotted a hat she remembers as the "Australian" model. “It went up on one side,” Landis remembers. “So I said, I’m going to take this one, I’m going to lower this side, I’m going to cut it to the length that we need it, shorten it.” Armed with measurements and a liking for the ‘sable’ brown felt, Landis briefed the hatters. “I said, please make it to these measurements. Go! They made 10 or 12, bespoke.”

Bespoke indeed. The item that rolled out of Herbert Johnson’s Old Burlington Street premises wasn’t as dainty as a trilby or as tall as a stovepipe, was more dapper than a cowboy and not as droopy as a bush hat. Indiana Jones’s fedora had elements of all yet resembled none. With the costume in her luggage, Landis shipped out to France for the first days of filming.

Then came the matter of making the getup look like it’d had both years—and mileage. “The first night we were in La Rochelle, after dinner I went down to the pool,” Says Landis. “I had brought sandpaper, Fuller’s Earth, mineral oil, a steel brush. Harrison came and sat with me and we just drank, and I aged the jacket and the hat.”

After much twisting and crushing, the hat’s accidental finishing touch was the "turn": the asymmetric sweep of the brim caused by the hat rotating slightly and distorting according to the shape of the wearer’s head. It was certainly singular enough that the character could be identified by his shadow alone. But to Landis, this idea was already old hat.

“I designed The Blues Brothers. You would know [them] in silhouette, in a second,” Landis says with a smile. “The head, the hair, the hat—it gives strength to a costume. John [Belushi] and Danny [Ackroyd] never take their hats off. And I went from one film to the next.”

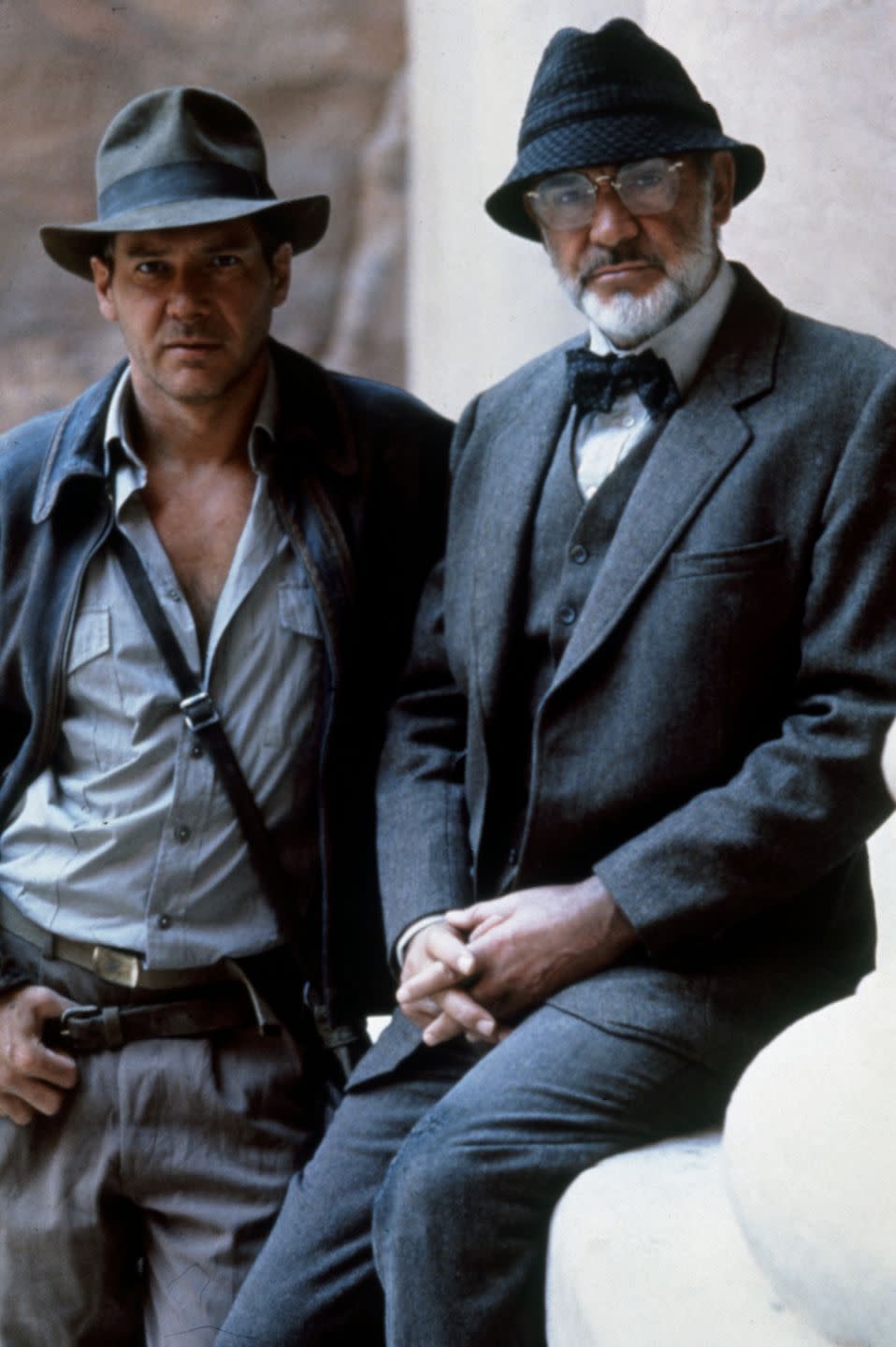

As the movies rolled on, the fedora gained its own character arc. It risked its owner’s life when it was snatched from beneath a descending door in 1984’s Temple of Doom. In 1989’s The Last Crusade it gained billing ("The man in the hat is back!") and an origin story, placed on the head of young Indiana Jones (River Phoenix) by an artifact-hunting scoundrel he’d impressed. This almost repeated itself in the closing scene of 2008’s Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, only for Jones Snr to snatch it back from his son (Shia LeBouf) with a grin that said: "I ain’t done with that." As this summer’s Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny proves, he wasn’t.

With individual hats evolving their own character and the design receiving nuanced updates throughout the saga, the quest amongst fans for the most screen-accurate fedora became perilous. Online forums would pick over the merits of felt types, shape, consistency and color. And with the mass-produced "official" versions hardly passing muster, cottage manufacturers would attempt to create their own hats to varying degrees of success. The most notable of these was Mississippi-born Steve Delk’s efforts which, in a step-change from Herbert Johnson, saw the hobbyist hatmaker triumphantly supply the production of The Crystal Skull with the hats Ford wore.

As the character’s icon status grew, rumors and misinformation amongst fans over where Indy’s paraphernalia originated eventually reached Landis. “I’m so glad I didn’t die. Everyone else would have taken credit for every single thing I ever did in my life,” Landis says with a weary smile. “I don’t own a design patent on the Thriller jacket, for instance. I have no money in the game. And there’s a lot of money to be made.”

Though stating that she generally doesn’t bother getting involved, “as a lark” Landis remembers calling out one-such false claimant—on Indiana Jones’s jacket design. “I wrote: I’m Deborah Nadoolman. I’m the mother of Indiana Jones. He is my child. I’m still alive. And I was there.”

The creation of the hat, too, remains conflicted. The late Herbert Johnson hatter Richard Swales insisted the fedora made for the films was simply a modified version of an existing model, the "Poet"—with a shallower ribbon and a quarter-inch trimmed off the brim—which Spielberg and Ford chose personally from the store. Brazilian hatters Chapéus Cury also laid claim to the hat, declaring its Cury rabbit fur was the raw material for the "blanks" shipped to Herbert Johnson.

In any case, after enduring financial hardship in the 1980s and 1990s, Herbert Johnson are today ensuring their current Poet line reflects the screen hats with commendable accuracy. Models featuring nuances from different movies—scenes, even—are made bespoke, and the hatters claim "return Herbert Johnson’s in-house craftsmanship to the very highest quality." Using fur felts sourced from the European food industry, the results aren’t cheap—around $630—but represent perhaps the ultimate tribute. That the hat Ford is wearing for his final 2023 whip-crack is again made by Herbert Johnson—the "Destiny Poet"—seems a fitting a way as any to close the circle.

“There’s a clear and strong DNA running through Indy’s hats. You can always tell it is his,” says Herbert Johnson’s current Master Hatter Michelle Poyer-Sleeman, who worked with designer Joanna Johnston—who oversaw 1989’s Indiana Jones and The Last Crusade—to develop the last of Ford’s fedoras.“Whilst Joanna was unable to share information on the film script, she was able to let us know we were designing a hat which Indy might have realistically chosen if he had walked into our store at Herbert Johnson in the 1960s,” adds Poyer-Sleeman. “The resulting design is unmistakably Indy’s fedora but it also very much has its own nuance and character.”

But for some collectors, even this indisputably screen-correct model won’t quite be the ultimate. In 2018, one of the few original movie hats outside of Lucasfilm’s archive—screen-matched to much of Raiders of the Lost Ark and signed by Harrison Ford—resurfaced in a Prop Store auction. “Film props and costumes on one hand can be incredibly simple, but on the other hand the greatest thing in the world. The Raiders fedora is a good example of that,” says Prop Store’s Brandon Alinger. With a hammer price of $522,110, the hat was amongst the most valuable items the auctioneer ever handled. “It’s the recognizability that causes it to command such a premium,” says Alinger. “The physical construction is quite humble—it’s a shaped piece of felt with a ribbon on it. But it does indeed have a magic. You can hold it in your hands while watching the film and see that exact hat on screen. It’s a vessel for connection… as close as someone could get to being there on set.”

Deborah Landis, today Director and Emeritus Professor at UCLA’s Copley Center for the Study of Costume Design, admits she is ‘shocked’ at the film’s enduring appeal—but her passion for her creation is clear. “The thing about a fur felt fedora… when they’re born, they have no shape. They’re just flat pieces of felt,” says Landis. "They respond to touch, because they’re fur. But it’s not until you wear them, you shape them, they have human oil… that they become part of you.”

She adds: “Would I have done anything different with the costume? Not at all. And that’s huge for a designer. I created that costume with a lot of love.”

You Might Also Like