A Little Free Library and letters from prison: How KC couple funded Bobby Bostic’s degree

In prison, education was Bobby Bostic’s north star.

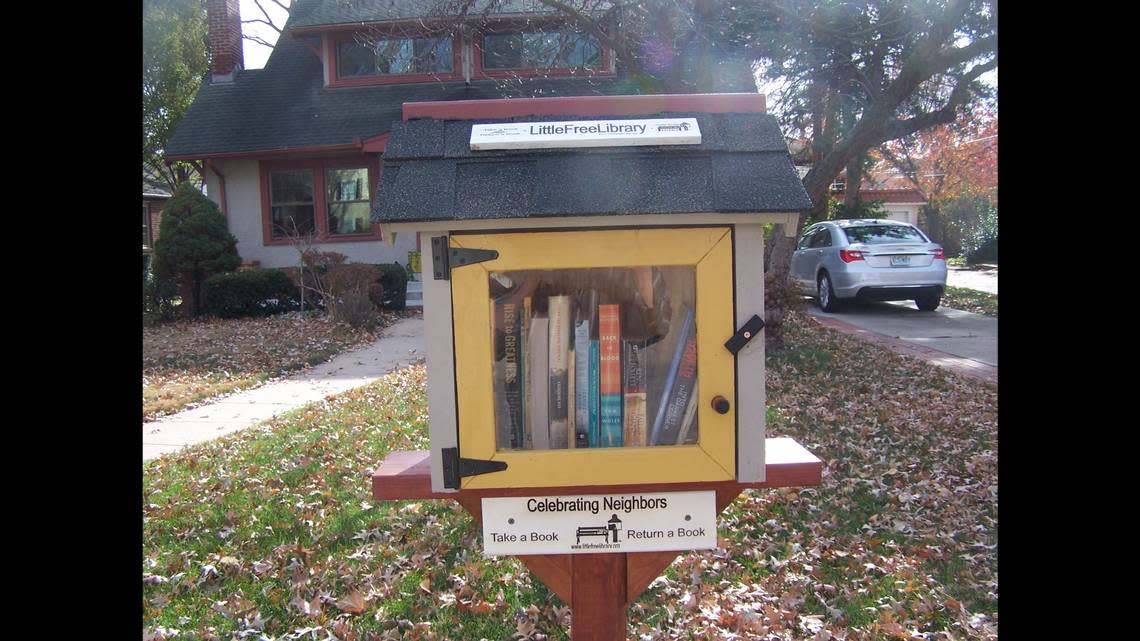

He frequented the prison library, where he’d also catch up on local happenings in the newspaper. One morning about a decade ago, an article about a Little Free Library in Kansas City’s Westwood neighborhood caught his eye. The way he remembers it, he saw a photo of the small house filled with books, and wrote down the address visible on the house in the background.

Seeing an opportunity to befriend a kindred spirit, he wrote the homeowner a letter.

Linda Parkinson wrote back.

Bostic was writing many letters at that time, including notes to hundreds of colleges, civic organizations and churches asking for support.

At the time, Bostic had become the face of a movement to end harsh sentences for juveniles convicted of non-homicide crimes in Missouri. He was imprisoned at the age of 16 and was told by a judge that he would die in the state’s custody.

But unlike the others, Parkinson actually responded.

“In prison, that’s all I did was read and wrote books, so my letter to her was strictly about books and the love of art. Based on that, we connected,” he said.

Eventually, Parkinson and her husband offered to pay for Bostic’s college courses through Adams State University on the condition that he only take one or two classes at a time, and that he keep his grades up.

Bostic went on to earn his associates degree in 2020. Parkinson passed away suddenly about a year later, about 18 months before Bostic was released from prison thanks to a law he helped reform.

Now the 44-year-old is doing what he can to give back in Parkinson’s memory.

241 years

Bostic was 16 when he was convicted of kidnapping, as well as multiple counts of robbery, armed criminal action and assault in St. Louis. He and an 18-year-old committed the crimes; at one point a gun was fired, causing a grazing injury to one of the victims.

The teenager was sentenced to 241 years in prison in 1995. He was initially not eligible for parole until he was 112 years old.

In prison, he completed his GED and started reading about juvenile justice, philosophy and sociology. Bostic started looking at his own experience through new lenses.

“If I hadn’t been exposed to education, I’d have thought that 241 years was my destiny,” he said.

Some men in prison started asking why he bothered taking college courses while facing a life sentence. By that time, Bostic started to believe he was destined to die in prison.

He started advocating for himself. And others did, too.

In 2018, retired Missouri circuit court judge Evelyn Baker, who sentenced Bostic more than 20 years ago, told The Washington Post she regretted her decision.

“I see now that this kind of sentence is as benighted as it is unjust. But Missouri and a handful of other states still allow such sentences,” Baker wrote in The Post at the time.

In 2021, after years of speaking out, a bill was signed that made minors convicted of non-homicide crimes eligible for parole after serving at least 15 years in prison.

Bostic was among about 100 other prisoners who were able to apply for parole, according to the Department of Corrections. Bostic was released from prison on parole in November 2022.

“Bobby demonstrates what we all know: who we are as children does not forever demarcate who we can become as adults,” Tony Rothert, the ACLU of Missouri’s Director of Integrated Advocacy, said at the time.

An unlikely friendship

Bostic saved up money in prison to pay for his first two courses. They were $670 each, not including books. He knew it would take too long to save up for the course load required for a degree.

That’s where Parkinson came in. But she didn’t just help financially; she also imparted discipline and hard work in studying, her husband and Bostic said.

Parkinson began visiting Bostic in prison about once a month.

She was even kinder in person than in the letters, he said, but she was stern about education. She wouldn’t pay for the next class until he passed the one prior. It took him four tries to pass math.

But he didn’t mind. The routine kept him sane. The deadlines gave him something to look forward to.

Meanwhile, Bostic said, Parkinson taught him there are good people in the world who don’t judge people’s pasts. It was in character for her.

Parkinson was always looking for opportunities to serve the community.

Parkinson told The Star that his late wife was hyper aware of social issues. She took on enormous amounts of volunteer work in Kansas City, including at Gordon Parks Elementary School, Operation Breakthrough, Crossroads Academy, CASA, Carver Dual Language Elementary, Cherith Brook Catholic Worker House and Morning Glory Ministries.

After Linda Parkinson started connecting with Bostic, the couple decided to set aside funds for his education. They’d read about his case, and they had a good feeling he would eventually be freed.

She was an entrepreneur at heart, Parkinson said, and Bostic’s story and attempt to sell himself as a worthwhile investment stuck with her.

“Their relationship was stronger than us just supplying money. Linda became a mentor for Bobby, I think,” Parkinson said.

Parkinson herself enrolled in college later in life. But once she started, she was on a roll, earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology, then another bachelor’s degree in philosophy and a master’s degree in psychology. Robin Parkinson has a bachelor’s degree in engineering and masters degrees in liberal arts and arts in marketing.

“Education really does open doors,” Robin Parkinson said.

Linda Parkinson died in May 2021 at the age of 68.

In the comments of her obituary, several people recalled her catch-phrase, of sorts: “Love is a verb.”

Parkinson said his late wife had it printed on cups that she would give away, and on a big poster they kept in their home.

After Parkinson died, her husband took up the letter-writing with Bostic. They’ve not yet met in person, but Bostic has an open invitation to dinner when he’s in next in town.

Paying it forward

In the nearly 10 months that’s he’s been out, Bostic has continued to write and publish books, his latest coming out soon.

He started a nonprofit called Dear Mama, and he mentors youth at three juvenile detention facilities, teaching them to write: essays, business plans, poems.

He tells people about his life; the life he’s living that he never expected to gain.

A professor from Massachusetts is helping fund his final coursework required for his next degree. He’s nine classes away from a bachelor’s in sociology.

“A lot’s changed since I’ve been out. I’m just living life to the fullest, enjoying it,” he said.

The memory of Parkinson’s kindness fuels much of his work. Years ago, when Bostic thanked Parkinson for her kindness, he said she urged him not to thank her, but to pay it forward.

“I want you to help somebody else out in the future,” she said.

“OK, I will,” he promised.

He hopes to soon start a scholarship in her name to send under-served youth to college.

“Education told me that the world is way bigger than what I thought it was,” he said. “Education is a freedom. It just lifts you up and lets you know anything is possible.”

Meanwhile, the Little Free Library that started it all still stands. It’s on its third renovation in about a decade, worn down by weather.

What started as a desire to spread knowledge within the Parkinson’s neighborhood ended up fueling a friendship based around education and literacy that culminated in a college degree and new insight into the world beyond the bars that once contained Bostic.

It’s the kind of story one can never imagine when staking a tiny library into the front yard, Parkinson, 71, said.

He sees another moral to this story, aside from the obvious power of education: “If you’re open to life, you don’t know what paths you’re going to cross.”