Woman returns heart-wrenching Holocaust letter to family 75 years later: 'My pain is unspeakably big'

Like many teenagers, Chelsey Brown did not exactly have a passion for genealogy when she was growing up.

Brown’s father worked in the field for years, and as she puts it, she thought it seemed “boring” at first. She watched him build out family trees for clients — sometimes for free. Instead of following in his footsteps, she pursued a career in television production and interior decorating.

“I was not interested in it at all,” 28-year-old Brown told In The Know. “But it’s like a full circle because I totally get it now.”

The full-circle moment started in 2019 when Brown’s family visited her grandparents’ graves, and she noticed an unnamed baby’s grave next to theirs. The baby had passed away less than a year after being born sometime in the 1930s. Something about the visual broke Brown’s heart, and she asked her dad to help her track down the family.

“Long story short, it took a few months, but we were able to find the family of that little girl,” Brown said. “We found her grandnieces. There was a myth in the family that the grandparents had a child, but they never liked talking about it because it was too painful for them. And no one knew where this baby was laid to rest. No one knew if there was [even] a baby.”

The grandnieces sent an email to Brown and her dad, thanking them for sharing the discovery. They signed off with, “Now she will never have to be alone.”

“From then, I really became interested in genealogy,” Brown explained. “And it wasn’t until last summer that I started returning heirlooms.”

Brown is still a professional interior decorator, but on the side, she’s an “heirloom detective.” She sources items like letters, photos and jewelry from flea markets and antique shops around the country. She then uses technology like MyHeritage to build out family trees and try to find the living descendants.

“I know those items should be with family,” she said. “So one day in summer of 2021, I just decided to pick something up for $1 to see if I could return it, and if I could, I could. Since then, I just have never stopped.”

The one story that stays at the forefront of Brown’s mind is when she returned a letter from a Holocaust survivor to her descendant 75 years later.

“That project took me about three months from conception to completion,” she said. “It was actually one of the hardest projects I’ve worked on.”

Many Jewish survivors of the Holocaust lost most or all of their personal belongings and valuables. Reuters reported in 2010 that there are more than 10,000 works of art alone that were looted from Jewish people in France and Belgium during World War II that have not been returned to families.

“Many [Holocaust] documents are sold underground or [at] auction for extremely high prices illegally — it’s totally illegal, but no one talks about,” Brown added. “I truly believe these items [should] go back to their rightful families. I don’t think people should be profiting off of them, and more importantly, I don’t think they should go to museums.”

Under the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947, “all unclaimed movable Jewish property was to have been returned to the communities of the survivors.” Yet auction houses and private collectors still try to buy and sell these items.

In 2008, a Tel Aviv auction house faced backlash after auctioning off items from the Holocaust. Survivors criticized the event and the auctioneer, who argued that “the heirs do not appreciate these things … If they wouldn’t be sold, they would just be thrown out and lost and forgotten.”

Dr. David Silberklang, a senior historian at the International Institute for Holocaust Research, slammed the auction in an interview with NPR, calling it “an indignity to the people who were killed.”

So when a flea market dealer Brown had formed a relationship with told her that he had some Holocaust documentation in his inventory, she knew she had to get ahold of it — not to sell, but to return to its rightful owner.

“For the next month, I kind of sweetened him up,” she said. “But he even told me — he was like, ‘I won’t sell any of this to you because I can get thousands for [it].'”

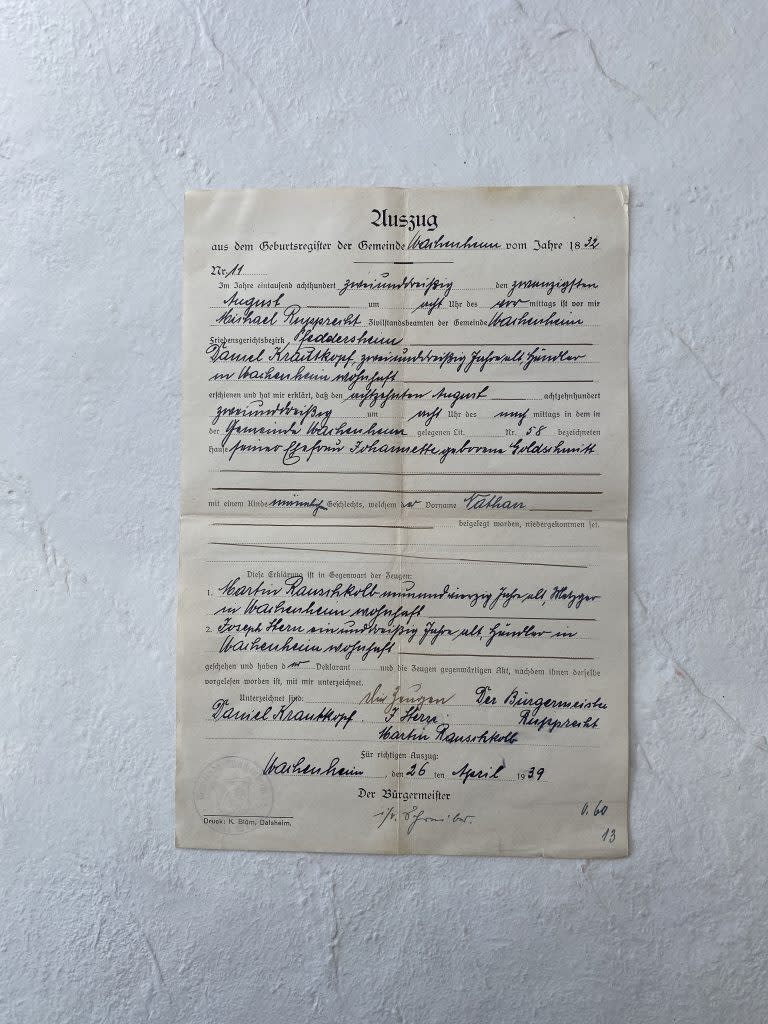

Brown somehow convinced him to show her three items: A document outlining what happened to a woman throughout World War II, a birth certificate and a letter. Everything except for the first document was in German.

“I told him I could translate some of this stuff for [him] because he didn’t know what any of it was,” she said.

Brown does not speak a word of German.

“I totally lied to the guy,” she laughed. “I wish I could have bought everything, but I just don’t have that money. So I bought things that I knew would be important not just to find this person, but like [the family’s] most sacred items.”

Someone on Instagram ended up translating the letter for Brown, which was written by a woman named Ilse on July 18, 1945:

“Through the kindness of our liberators, I am able to give you a sign of life from me after so many years… Dad, Mom, Grete, Lottchen and Hermann: No one is alive anymore. My pain is unspeakably big. My husband, whom I married 3.5 years ago, was also taken from me! … When there will be a regular mail connection, I will tell you everything in detail.”

Using Ilse’s birth certificate, Brown got to work using MyHeritage to figure out if there were any descendants to whom she could send the documents.

After months of research, Brown was able to piece together Ilse’s family tree; she was born in Germany and grew up with three sisters, only one of whom survived the Holocaust. Ilse had joined an underground resistance group before getting arrested in February 1943 and being sent to Auschwitz.

During her train ride to the concentration camp, Ilse jumped and escaped to Berlin. After hiding for about a year, she was caught and remained in a Berlin prison until 1945, when she was liberated by Russian troops. It was then that she wrote this letter to her only remaining family member, her sister Carla.

Ilse and Carla then immigrated to the United States in 1948. Neither of them had children, but Ilse got married again, this time to a man named Ludwig, who did have a child.

Ludwig’s child ended up having a daughter named Jill, who Brown found online. Jill is Ludwig’s granddaughter, and she lives one state over from Brown.

“I remember messaging her on Facebook, and I know she thought it was a scam at first because she read my message and wouldn’t respond to me,” Brown said. “I persuaded her to get on a call with me, and we were just on the phone for two hours talking. I mean, she was in shock.”

Jill knew both Ilse and Carla — they were at her wedding, and she called Ilse her auntie. They were very close, and according to Brown, Ilse and Jill even traveled to Germany together about 30 years ago. Ilse passed away in September 2001 at the age of 93.

“I think it was just really special for Jill to get these documents back,” Brown said. “And it was special for me to get these off of the market.”

Jill also helped Brown fill in some of the holes in Ilse’s story. For example, Jill knew that a family had helped Ilse hide in Berlin after she jumped off of the train because Ilse kept in contact with them and sent them supplies after the war as a thank you for helping her stay alive.

“Ilse‘s story is a permanent platform for what I do and why I do it,” Brown said.

While Jill was reconnected with Ilse’s documents, not every story ends the same way. Although Brown is doing everything she can, she still is a single-person operation trying to return family heirlooms for free while maintaining a full-time job.

“It’s [awful] that we have these vendors profiting off of these victims, and of course, I’m not trying to contribute to funding them, but I do want these back to their rightful families,” Brown said. “Did I want to pay him for the documents? No, but I needed to.”

As recently as 2021, illegally confiscated and obtained documents and priceless historical heirlooms have been seized by governments all over the world.

“These heirlooms can tell you things that no record ever could,” Brown said. “They can tell you someone’s personality, their feelings, their hopes, their dreams, their sadness, their pain.”

Brown has found success posting about her hobby on social media, and she credits the emotional nature of heirlooms for people’s interest in her content.

“This shows that there’s magic behind the lives of average people,” she said. “I think that’s what people connect with, too, because these stories that I find are absolutely miraculous.”

As for her dad, he could not be more excited that there’s another genealogist in the family.

“His daughter now, for the rest of her life, is going to carry on this passion of genealogy,” she said.

The post Woman returns Holocaust letter to family 75 years later appeared first on In The Know.

More from In The Know:

Here's how to see what phase the moon was in on the day you were born

Dangerous 'one chip challenge' on TikTok allegedly leads to multiple hospitalizations

Hot take: Pizza scissors will cut your pizza better than a wheel

The best Valentine’s Day gifts for 8 types of men — the foodie, homebody, techie and more