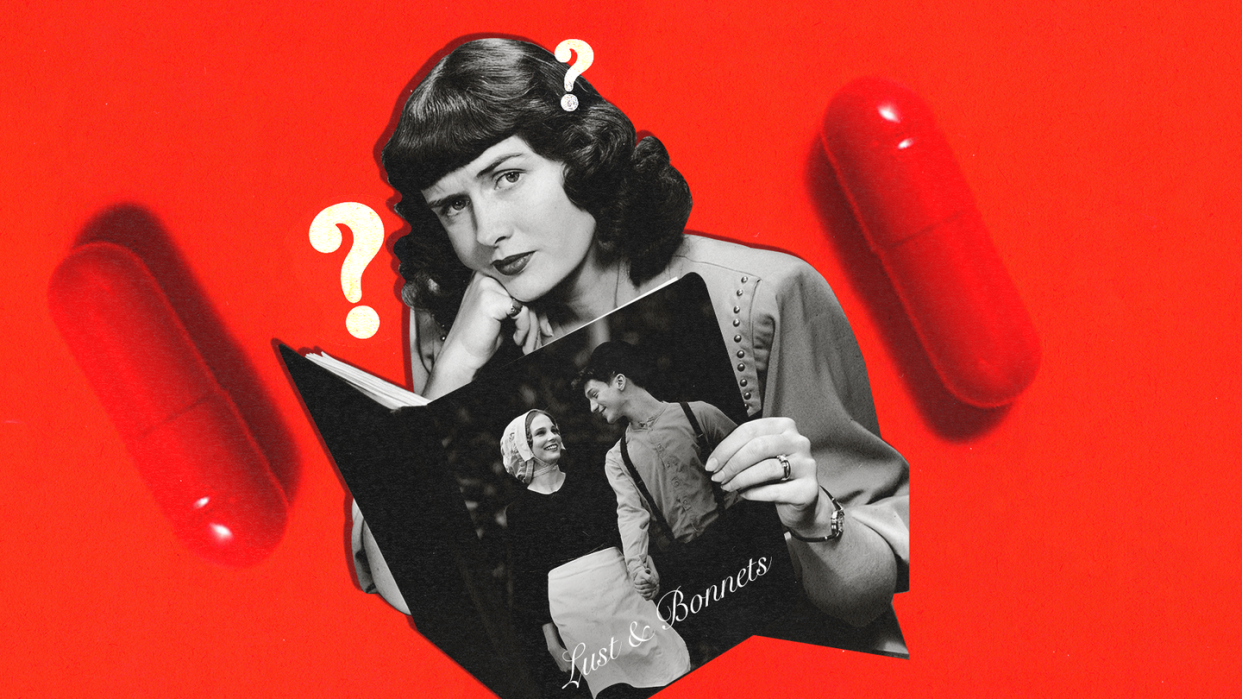

Uh-Oh, Are Amish Romance Novels Red-Pilling Me?

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Tess McCallum was on a romantic weekend getaway with her girlfriend in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, when she came across a book she had to have: The Cowboy’s Amish Haven. The couple had stumbled into a thrift store and, amid the trinkets and wool sweaters, McCallum, 24, found a shelf of books with covers depicting young women wearing bonnets. They were all Amish love stories, and the Western twist of Amish Haven especially stood out to her. “I’m an avid romance novel reader, and I thought, This is perfect—because I’m also very into learning about subcultures and religion,” she says. “I finished the book in record speed.”

McCallum didn’t know at the time that The Cowboy’s Amish Haven wasn’t just a quirky thrift-shop-find in a small county known for its Amish population. It was actually an example of one of the most popular and enduring romance subgenres you may have never heard of: Amish romance, which has been a reliable money-maker for publishers since the late 1990s. “It’s a joke, or half joke, in the industry that if you really want to sell a book, you put a bonnet on it,” says Daniel Vaca, a professor of religious studies at Brown University and author of Evangelicals Incorporated: Books and the Business of Religion in America. Today, you can find the not-quite-steamy stories in libraries, bookstores, and on bestseller lists. The Evangelical Christian Publishers Association bestseller list consistently features Amish fiction in its top 25 titles, an average of three a month from March 2022 to June 2023, according to Bethany House, the largest independent Christian book publisher. The genre also boasts several New York Times best-selling books and authors, while the Amish romance category on Goodreads shows the books have tens of thousands of reads and reviews.

To an outsider, these so-called “bonnet-rippers” look placid and innocuous. Notably, no bonnets are actually torn within the pages of these books—in fact, chastity reigns. The novels almost always have “happy” endings. For instance, in Once Upon a Buggy, the main character May ends up with her childhood crush Carl (even after he was tragically burned in a barn after the couple broke the rules by being alone together without a chaperone). Some staple themes of the genre include: repressed yearning, consequences for “sins,” prayer, and mouth-watering descriptions of food (usually prepared solely by women).

But in depicting this bucolic, “simpler” world, authors often tout hard-line Christian values, traditional gender roles, and a very white way of life. Maybe in a different time, the popularity of the novels could be seen as harmless, healthy escapism—the indulgence of a fond, delusional fantasy untethered from modern life. But alongside the rise of TikTok #tradwives, conservative edgelords insisting that women are only truly fulfilled when they’re married and procreating, and the increasing assault on reproductive rights, it’s worth wondering if there’s something more ominous about this longing for an olden, gendered way of life.

I first learned about the Amish romance craze from my mom, who’s a librarian in small-town Iowa, where the genre is a hit. I was immediately fascinated. Were these books harmless oddities or emblematic of something bigger and more noxious in the literary waters? Were they reinforcing conservative values for readers who were already aligned with those principles or romanticizing this lifestyle for new ones, like McCallum? I started cracking open books with titles like A Christmas Bride in Pinecraft, The Cherished Quilt, and, of course, Once Upon a Buggy to find out.

I soon learned there’s more to these books and their staying power than I imagined. Their lasting popularity may be attributed to the same reasons why your TikTok FYP is filled with trends like Slow Living, sourdough starters, and #Homesteading.

Perhaps that’s how they’ve picked up readers like McCallum. “You’re probably wondering why would I read this as a 24-year-old queer woman?” she said “Reading it, I absolutely knew this was not written for me. But that’s what drew me in more.”

Amish romance was really born in 1997, when Beverly Lewis, the so-called “queen” of the genre, came out with The Shunning, about a young girl who doesn’t quite fit in with traditional Amish life. It’s not strictly romance per se, but it has the glimmers of yearning that are a hallmark of the genre and is loosely based on Lewis’s own grandmother, a Mennonite who eventually left the community. The book sold more than a million copies (and was later made into a Hallmark drama). After the book exploded, “People were saying I created a genre,” Lewis tells Cosmopolitan.

Interest ramped up in 2006, paradoxically, after a devastating shooting at an Amish schoolhouse resulted in the murders of five little girls, which made national news. But then something just as bewildering happened: The community offered the shooter’s family forgiveness. The episode kicked off a renewed fascination with the Amish—one that might even border on fetishization. Valerie Weaver-Zercher wrote in her 2013 book Thrill of the Chaste: The Allure of Amish Romance Novels that the Amish became “containers into which non-Amish readers can pour their own personal cocktail of anxieties and longings.”

In her research, Weaver-Zercher found that in this era post–The Shunning, the publishing industry was “beating the bushes to find new Amish fiction authors.” Very few of them were actually Amish, which Weaver-Zercher notes can be seen by some as cultural appropriation. “The more white evangelicals fall in love with the Amish and write novels about them, the less the Amish are allowed to be who they are.”

One of the only popular Amish romance novelists who’s actually Amish is Linda Byler, who answered questions from Cosmo via snail mail. Byler says it’s hard to portray a culture perfectly that you’re not a part of. “My books likely differ from others, in that I write honestly, as our lives really are—not as they appear,” she adds. “We probably appear to live idyllic lives of peace and harmony. The horse and buggy clopping down the road on a gentle spring day brings an aura of stepping aside from what I imagine is a hectic lifestyle. The real truth, however, is the fact that we have our own self-imposed busy schedules.”

Byler has plenty of fans in the Amish community, says Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, author of The Lives of Amish Women and distinguished service professor of anthropology emerita at SUNY Potsdam. “The Amish women that I’ve talked to here—who are Swartzentruber Amish, among the most conservative of all Amish—about these novels, they all said Linda Byler’s were the most accurate and reflective of Amish life,” Johnson-Weiner, says. “They said that other books might be about ‘other’ kinds of Amish. They’d see people do things in the books that had nothing to do with their lives.”

But built largely through the imaginations of writers who aren’t living those lives, the Amish romance trend has continued for years longer than authors and even publishers expected, which brings us to today.

Certain avid Amish readers, like Elly Gilbert, 46, enjoy some of the Christian themes of the books, but don’t agree with the more rigid social mores. “They prioritize family time and structured life, which I do admire,” she says. But she also adds, “I think traditional Amish culture does promote a more male-centric, women-are-submissive-to-their-husband type of role," she says. Still, it didn’t keep her from reading 50 of the novels last year. Gilbert is such a big fan of the genre that she entered and won a contest to cowrite an Amish book with another author, where she tried to be the change she wanted to see in the Amish romance world. “That’s something I pushed back against in my book,” she says of the gender roles and harsh rules often depicted elsewhere in the genre.

For others, like Pam Burke, 68, a retired math teacher from Missouri who estimates she owns “about 400 Amish books,” the novels do indeed reinforce her existing values. She’s so into Amish romance that she and her husband also went on vacation to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, stayed with an Amish family, and even attended an Amish church service. (Burke was prepared for it, thanks to her extensive reading: “It’s three hours in a barn on backless benches, and it’s almost all spoken in German.”) Burke adds that she almost exclusively reads Christian fiction and agrees with many of the ideals put forth in Amish romance novels—and that she appreciates that they’re so “clean.”

Suzanne Woods Fisher, a non-Amish author who has written 30 Amish books over the past 15 years, says ultimately that the books scratch a certain itch for people all over the political, age, and economic spectrum, with lessons about forgiveness, humility, and community. “With loneliness as an epidemic and the fractured political scene, there’s a lot in our country that needs healing,” she says. She compares the phenomenon to Ted Lasso, which she loved “except for the swearing.” “There’s a part of us that’s just drawn to those characters who surprise us with their goodness,” she says. “Where does that goodness come from? There’s something about it that’s just calling us to a better life.”

But who decides what’s “better?” Amish romances take care to mostly feature “good” people who are doing the “right” thing. But so often men, God, and patriarchal structures are the ones deciding where the line is.

As I tunneled deep into the world of Amish fiction, there were times I felt…like my brain was breaking. On the one hand, I was having a hard time with the bonnet-white characters, the gender roles, and the messages of guilt and shame around sex. On the other, I found myself absorbing some of the more wholesome lessons and values, especially around forgiveness and redemption. I have to admit I was also oddly transfixed by the fantasy of learning how to make sourdough instead of answering emails hunched over my laptop all day, or tending to my pet alpacas named after Santa’s reindeer (this, again, a real plot point from Once Upon a Buggy).

It’s the same part of me that still can’t stop scrolling through TikToks about “stay-at-home girlfriends,” and #tradwives. On days I’ve girlbossed too close to the sun, I can see the appeal of a slower-paced life. Of having someone provide for me so I don’t have to worry about rent. Although I know this fundamentally goes against my ideals, I can see why a world where other people decide what’s best for you is comforting, a reprieve from the grind. As Physicist Barbie says when she gets brainwashed by the Kens in Greta Gerwig’s Barbie: “I like not having to make any decisions—it’s like a spa day for my brain. Forever!” And then I remember that Physicist Barbie and I would have to make dinner for our respective Kens every night…literally for the rest of our lives and never do anything else (except, perhaps, watch them cover Matchbox Twenty).

In Amish fiction—as well as #tradwife culture and the conservative vision of breadwinning men and stay-at-home women—this lack of agency is often presented as idyllic. And it makes sense that we want to relinquish our control in a world that feels increasingly overwhelming. Fisher urged me to ask: “Why is it soothing? What is calling to you? I’m not saying the Amish are telling you how to live—maybe it is just a calmer life, a quieter life, without technology undermining how you feel about yourself.”

But Weaver-Zercher points to something far more insidious at work here. “There is a generalized social and cultural anxiety around gender roles, and white evangelicals especially feel embattled or persecuted or like they can’t keep up,” she explains. “So there’s a retreat to stereotypical gender roles that feel safe. It lets you pretend the world isn’t changing in the ways you don’t like.” But imagine how that feels if you don’t fit into that sepia-toned world or you want something different for your life. “If you’re a queer kid growing up in a white evangelical context, and these are the books at your church library? A steady diet of Amish romance novels for any person who doesn’t fit in some way? It just would be a literary layer of shame.”

Indeed, Robin Bradford, a librarian in Washington and author of The Readers’ Advisory Guide to Romance, said Amish romance novels represent the "MAGAization of romance” as a genre. “The MAGA movement also famously peddles nostalgia for some sort of imagined 1950s, pre-integration America,” notes Vaca. Similarly, lots of Amish fiction lets conservative readers burrow inside an “evangelical, white fantasy world,” as Vaca puts it.

I genuinely enjoyed probing the cultural meaning of Amish romance novels with critics like Weaver-Zercher and proponents like Fisher, just as I generally enjoyed some of the books I read. I felt the tug of so many contradictions, so much cognitive dissonance. I don’t want to kink shame anyone who likes a chaste read or who’s even turned on by the Amish either—there’s already been enough judgment and suspicion of women’s reading habits over the years. There’s also something to be said for burrowing inside a fundamentally different worldview, especially in such a polarized world.

But I do think it’s worthwhile to ask why, in 2024, so many of us—conservatives and not—are drawn into a white, patriarchal vision of the world where a woman’s driving purpose is to get married, have children, and churn butter, even if it’s all neatly wrapped in a bonnet. The same question applies to why TikTok’s tradwives and even Hallmark Christmas movies are culturally ascendant at the moment.

As for McCallum, she found reading the bonnet-rippers almost like an anthropological study. “I was definitely viewing the lifestyle as an observer, rather than someone who wants to put themselves in those shoes,” she says. “I could never be an Amish girlie. I like looking through the glass, but I’d never want to go through.”

You Might Also Like