Jumbo The Elephant: The Rise And Tragic Fall Of The 'Largest Animal On Earth'

Come one, come all! Step right up! Back in the 19th century, the circus was the hottest ticket in town when it came to entertainment. Bustling crowds would pile in under Big Tops, ready to be amazed by all manner of marvels and wonders. But one star above all others stole the show: Jumbo the Elephant. This was a period, remember, when most people had never seen an elephant before, so you can imagine how shocking it was for audiences to be confronted by this gargantuan creature for the first time. Jumbo was a star in the truest sense, but beyond the dazzle of the circus ring his tale is, sadly, riddled with tragedy.

Heartbreaking from the beginning

In truth, Jumbo’s life was heartbreaking from the very beginning. He was born in Sudan in 1860 and within the first couple of years of his life he was already being exposed to terrible trauma. As a calf he watched his mother’s slaughter at the hands of poachers, before being placed into captivity himself.

This poor baby animal had a strange life ahead. He would never be free, and he would soon be forced to travel the world for the amusement of another species entirely. The pachyderm was fated to become one of the most famous animals of all time.

A most bizarre odyssey

The young elephant was taken to Kassala, a city in Sudan, where, along with a bunch of other captured wild animals, he was sold to an Italian man named Lorenzo Casanova. Casanova was plotting a bizarre and difficult journey: he planned to take his strange ensemble of creatures on a 300-mile odyssey across the desert towards a port on the Red Sea.

Casanova’s group included camels, monkeys, cheetahs, birds, jackals, porcupines, and, of course, the baby elephant, among many others. Some were in cages, while others walked; it doubtless made for a most bizarre sight.

Animals on tour

Casanova’s motley crew traveled during the night, so as to avoid the intense heat of the day. As you might imagine, progress was extremely slow and it took them about six weeks to reach their destination. But for the imprisoned animals, there would be no respite. Once they finally reached the port, they were then forced to endure an 800-mile journey by boat to Suez in Egypt, followed by a train to Alexandria, another boat to Trieste in Italy, and finally another train to the German city of Dresden, where Casanova was based.

After that grueling journey, the animals were then forced to travel around Germany as part of a touring menagerie. But it was the elephant who started to attract the attention of other animal-exhibiting businesses. Before long, a Paris-based institution had purchased the young creature.

Making a deal

This transaction, which saw the French institution acquire the elephant, caught the attention of Abraham Bartlett, who was the head of London Zoo. He’d wanted to get his hands on an African elephant for a long time — none had ever been brought to Europe before — so he was left extremely annoyed that his French rivals had beaten him to the punch. He was determined to bring the creature to his zoo.

Bartlett entered negotiations with the French institution, and a deal was eventually struck. It cost Bartlett quite a lot: he had to hand over a kangaroo, a rhino, a possum, a jackal, two dingoes, and two eagles in order to get this one elephant.

A “deplorable, diseased, and rotten creature”

The deal didn’t seem like a great one from the perspective of an assistant keeper at London Zoo named Matthew Scott. The young elephant, as Scott later wrote in an account of the creature’s life, had been in terrible health at the time of the exchange. “A more deplorable, diseased, and rotten creature never walked God’s Earth,” as he put it. “The poor thing was full of disease, which had worked its way through the animal’s hide, and had almost eaten out its eyes.”

Even though the animal was in such a bad state, Scott wasn’t without hope that he could be brought back to health. So he started treating the creature, and eventually his condition improved considerably.

Jumbo’s lexical legacy

Word about the elephant eventually started to spread among the British public. While people during those days had knowledge of the Indian elephant, its African cousin was quite a different prospect. African elephants grow to a much larger size than their Asian counterparts, and people of the time were intrigued to see one in the flesh.

In London the elephant took on his famous name. Nobody knows who picked it, or even why they decided it suited him. After all, while we now associate the term “jumbo” with something large, that wasn’t the case back then. In fact, the way we use that word today traces directly to this elephant.

“The pet of thousands”

Jumbo’s publicity received another big boost when Bartlett managed to buy a female African elephant named Alice. This creature came to be known as “Jumbo’s wife:” this was a clever bit of marketing that clearly struck a chord with the public. People were really interested in Jumbo now, and soon Scott was training the beast to get him ready to give visitors to the zoo rides on his back.

Bartlett later wrote about these rides, noting, “His docility and good temper rendered him the pet of thousands.” That wasn’t an exaggeration; quite literally thousands of kids visited London Zoo and were allowed to ride on Jumbo’s back.

Meeting royalty

A sitting monarch was known to visit the elephants at London Zoo, which presumably means she saw Jumbo, too. Queen Victoria definitely saw the zoo’s Indian elephants, an experience she once wrote about in her journal. “They are quite tame,” she noted. “There were two quite little ones, who salaamed and were ridden about at an immense pace.”

Jumbo was around London Zoo at the time, so it seems very likely that she laid eyes upon him, too. And there are unconfirmed rumors, as well, that Winston Churchill may have ridden atop the elephant while he was a child.

Constant and increasing trouble

As Jumbo grew older, though, some pretty serious behavioral problems started to emerge. He was a teenager now, which came with a host of issues for his keepers. Bartlett once wrote, “He is amazingly intelligent, good-tempered, and tractable; at the same time he has given me, and everyone else who has had anything to do with him, constant and increasing trouble and anxiety.”

As he grew bigger, his strength increased accordingly; that meant his expressions of displeasure were a problem. Jumbo hated being locked away during the nighttime, for instance, and he made that fact clear.

Drastic means

Jumbo’s keepers, as Bartlett recalled, were perpetually left “altering, repairing, and making his house strong enough to keep him in it.” And the most worrying thing, as Bartlett saw it, was that there was only really one person who could control the aggravated elephant. If anything ever happened to Scott, there would be big trouble at the zoo, and drastic measures might need to be taken.

Bartlett expressed this fear in a document submitted to the Zoological Society’s council. Referencing the possibility of “illness or accident” ever befalling Scott, Bartlett ominously wrote, “In conclusion, I may ask that I should be provided with, and have at hand, the means of killing this animal, should such a necessity arise.”

A solution from abroad

Events never took such a drastic turn in the end, because a solution to Bartlett’s predicament materialized from abroad. A telegram came through one day, sent from Phineas T. Barnum. He was a famous showman and co-founder of the Barnum & Bailey Circus, and he wanted to get his hands on Jumbo. Given the price offered for the elephant and the issues he’d recently been causing, Bartlett was only too happy to make the deal.

Jumbo was heading to America, but there was outcry from the British public. As expressed by the writer John Ruskin in a letter, “England is not in the habit of parting with her pets.” People didn’t want to say goodbye to the iconic creature.

The Brits say their goodbyes

As Jumbo’s stay in London Zoo neared its end, thousands of people flooded into the institution to say their farewells. The whole place was overwhelmed with parting gifts: cakes, alcoholic beverages, a pumpkin, even oysters. Huge amounts of presents were left at the zoo as tokens of admiration for the elephant. Britain clearly didn’t want to see the beast go.

Jumbo, too, seemed reluctant to hit the road once again. The circus sent over a big crate for him to be transported in, but the elephant stubbornly refused to get inside it. Crowds gathered to smugly watch the spectacle unfold, pleased that the circus people were having such trouble.

A zoological civil war

In the background, meanwhile, a civil war of sorts had broken out among leading figures within the Zoological Society. One faction was extremely upset to see Jumbo go, so its members went down the legal route to try and stop the sale. And they very much had the public on their side.

The press was deeply interested in this whole episode, with plenty of articles being published in support of keeping Jumbo in the country. In the end, though, a judge ruled that the sale should be allowed to proceed.

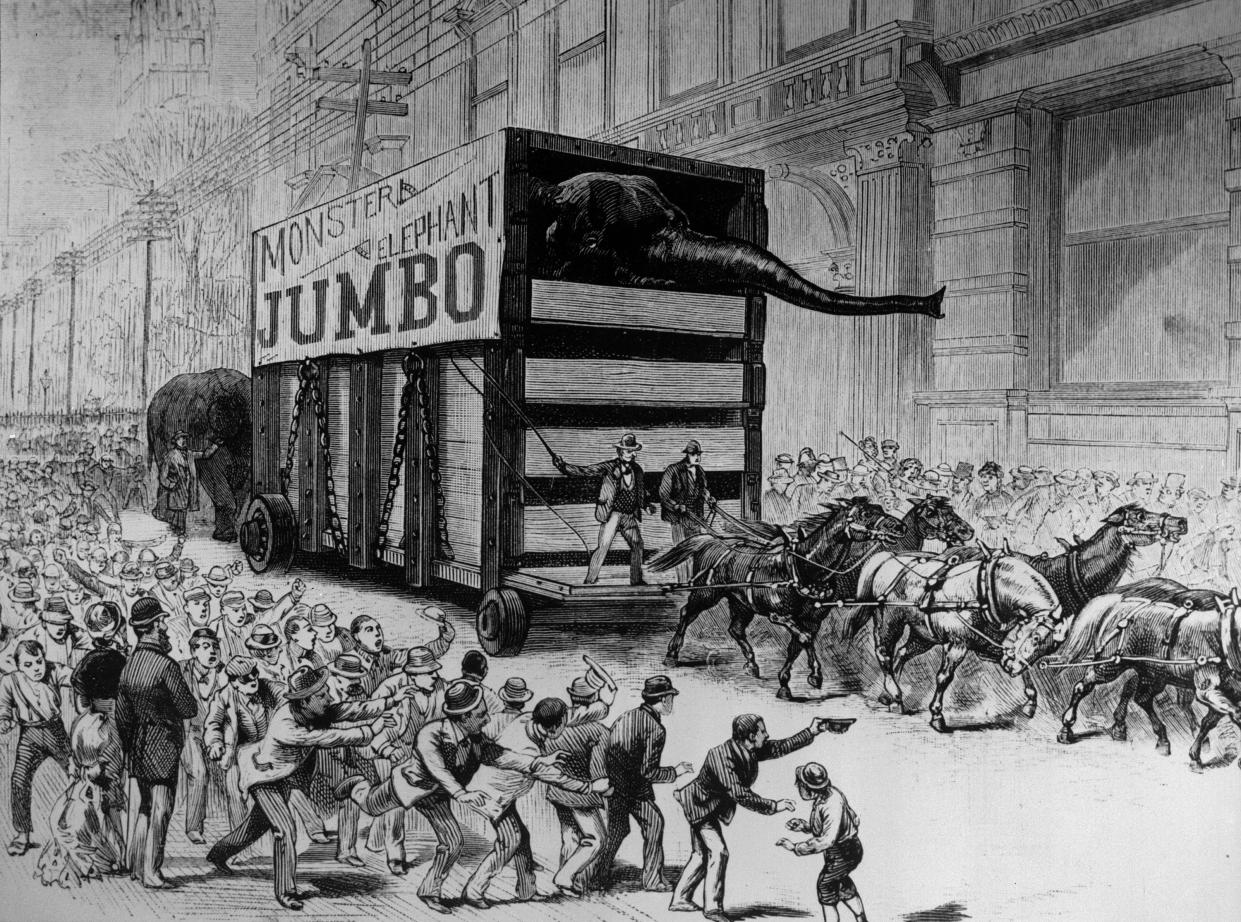

Back to sea

And that was that: on March 22, 1882, it was time for the final goodbye. Hordes of people took to the streets to watch as Jumbo was transported by horse-drawn cart to a steamboat along the River Thames. He hadn’t sailed for 16 years, so this experience may well have brought back traumatic memories from the poor elephant’s youth.

He was setting off on a new chapter of his already extraordinary life. He’d seen many countries by this stage and had found fame in London, but in America his star was about to launch into the stratosphere.

“The largest known animal in creation”

Jumbo’s time aboard the steamboat lasted a grueling 18 days, but eventually he made it to New York in one piece. There, he was awaited eagerly by a public who had come to know him as “the largest known animal in creation.”

That was obviously a clever bit of marketing — in other words, not exactly true — but it did the trick. Americans couldn’t wait to get a glimpse of the creature, as he set out on tour as part of Barnum’s traveling circus.

Awed by the steam whistle

Jumbo was greeted along the edge of the Hudson River early on April 10, 1882, by Barnum himself, along with some of New York’s most prominent figures, plus a couple of reporters. One of the newspapermen, writing for The Sun, noted, “The first seen of Jumbo was an enormous trunk, reaching far out from the front of his box, writhing and twisting in all directions.”

This journalist also mentioned how Jumbo behaved as the steamboat approached its destination along the Hudson. “During the trip across the river he was quiet,” they wrote. The steam whistle of the tug seemed to awe him.”

Slow progress

Witnesses there on the day, reportedly, were themselves left awed by the sight of the giant animal. It took a huge effort to transport Jumbo from the boat deeper inland, with 200 men and 16 horses called upon for the job. Nobody had seen anything like this before.

Progress was slow as Jumbo was transported through New York. He was taken along famous streets to Madison Square Garden, where Barnum’s circus was based at the time. For better or for worse, this was the start of the elephant’s new life.

Hitting the road

For the three years that followed his arrival in New York, Jumbo was a huge part of the circus. His career began with a month-long residency at Madison Square Garden, but after that had concluded it was off on tour alongside his circus colleagues. His life was on the road now.

The circus traveled mainly around the eastern parts of the United States, with stays in cities including Washington, DC, and Chicago, blowing people’s minds wherever it went. The troupe even journeyed into Canada for one stint.

“The Jumbo of Steam-Whistles”

It was during these years of touring around America that Jumbo’s name came to be used to refer to something huge. One early example of this usage came in an 1882 edition of The New York Times, when an article about “the largest steam-whistle in the United States” was heralded as “The Jumbo of Steam-Whistles.”

The following year, a large locust found in Utah was described by Harper’s Magazine as “the Jumbo of crickets.” The term eventually became so normalized that nowadays we have “jumbo” portions of fries and “jumbo” jets.

A marketable elephant

It became clear to many companies just how marketable Jumbo really was, and many employed his image in their advertising campaigns. The elephant was used to hawk washing powder, cotton, candy, jewelry, soap, and even medicines!

One campaign showed him appear alongside the likeness of Oscar Wilde! The connection between Jumbo, Wilde, or any of the products the elephant was used to sell was often tenuous at best, but clearly advertisers felt it worked for them.

Disaster strikes

Jumbo had become perhaps the biggest animal star who ever had lived, but the whole thing collapsed in the blink of an eye. In 1885 Jumbo and his circus mates were in Ontario, Canada, for a show in a place called St. Thomas. After the event had come to a close, Scott was directing Jumbo and some other elephants to walk on a railway track towards a carriage waiting for them.

You can probably predict where this is going. The railway track was very much in use, and before anyone had time to react, a freight train appeared and sped towards Jumbo. He couldn’t get out of the way in time.

The final moments

The New York Times reported on the tragedy. “As the locomotive struck the mighty monster it was as if two trains had come together, and the freight train was stopped, the engine and two cars being derailed,” the paper’s reporter wrote in the aftermath of the incident.

“Jumbo was struck in the hind legs,” the reporter continued, “and as the cowcatcher hit him he gave a loud roar and fell.” The unthinkable had happened, and it had spelled the end for this magnificent animal.

A star is extinguished

Horrifically, though, the poor beast wasn’t killed instantly. There’s no consensus on how long it took for Jumbo to die: some say 15 minutes, others claim 30. What does seem clear is that the elephant struggled for a short period, before he finally died. The biggest animal star in the world was gone.

Scott, who’d been with Jumbo since meeting him so long ago in London, was there when the tragedy unfolded. According to a report, “Long after his life was extinct his keeper, who brought him from the Zoological Gardens in London, laid on his body and wept.”

No resting in peace

You might think this was the end of it: Jumbo the Elephant, after a life defined by tragedy and suffering, dying in fittingly bleak circumstances. Now, surely, the poor animal would be permitted to rest in peace? Well, no. That’s not what happened. To the contrary, certain human beings’ unending desire to exploit the elephant for monetary gain ensured that, even in death, Jumbo would be put to work.

Barnum, with little hint of any sorrow at the loss of the animal, quickly got the ball moving. He sent the body to a top taxidermist, who was tasked with preserving Jumbo in a presentable state. The creature’s time on display was far from over.

“Let him show like a mountain!”

It’s been reported that Barnum’s instructions to the taxidermist were, “Let him show like a mountain!” The circus master really seemed to feel no shame about any of this. He would have done just about anything, it seems, in the name of turning a profit.

Speaking to The New York Times, Barnum was quite unapologetic about any of it. “If I can’t have Jumbo living,” he said, “I’ll have Jumbo dead, and Jumbo dead is worth a small herd of ordinary elephants.”

More morbid details

Within a week of Jumbo’s death, Barnum was getting to work trying to strike lucrative deals to put the elephant’s stuffed remains on show. The taxidermist charged with actually preserving the remains, meanwhile, was getting to work. He removed the animal’s heart and other organs and pickled them.

He later sold these organs to Washington, DC’s National Museum of Health and Medicine, which itself later sold the heart to Cornell University. Here it eventually deteriorated to such an extent that it was finally discarded. This is but one more morbid detail in the long, unfortunate tale of Jumbo.

Buying Jumbo’s “wife”

Barnum had even more ideas about how to capitalize upon Jumbo’s popularity, even after he’d died. He decided that he wanted to buy Alice, the elephant in London who had once been a companion to Jumbo. He envisioned billing her as “Jumbo’s wife.”

As a satirical piece in The New York Times put it, Alice was Jumbo’s “grief-stricken widow.” This, as far as Barnum could see, was a potentially lucrative angle, and he wanted to own the female elephant.

“My poor old Jumbo”

This satirical article described the moment, real or more likely imagined, when Alice first encountered Jumbo’s remains. “When Alice first saw the stuffed skin of Jumbo she seemed like one in a trance. Then she touched his skin with her trunk and again burst into a flood of tears.”

“She knew at last that he was dead, and as she looked into his glassy eyes and fondled his stuffed forehead with her trunk she seemed to say, “My poor old Jumbo, your Alice weeps for you.”

“No such thing as bad publicity”

Even if The New York Times piece was making fun of the crazy situation, it also served to encourage it. Barnum himself is once said to have remarked, “There’s no such thing as bad publicity,” and all these stories about Jumbo and Alice served to keep him in the public’s mind. And with that, Barnum stood to make even more money.

Jumbo was back on tour, even in death. For the next few years his remains were carted around America, before making a return to London once again. To today’s eyes it all made for a morbid spectacle.

Another barbaric act

After the London exhibitions, Jumbo’s remains were brought back to America, and yet another act that might be regarded as barbaric by today’s norms was committed. Now even Jumbo’s stuffed remains were violated: his skin was separated from the rest of the body. His skeleton was sent back on tour and the skin was despatched to Tufts University.

Barnum had close links to this educational institution. Anne Sauer, an official from its Digital Collections and Archives division, was quoted by The Guardian as saying, “Jumbo was clearly a gift intended to raise the profile of the college... Barnum hoped it would attract attention and renown.”

A home in New York

As for the skeleton, that had originally been destined for the Smithsonian Institution, but then Barnum came up with a new plan. He’d felt slighted by the Smithsonian, as it, from his own perspective, had failed to donate enough items to go on display at his own fledgling museum at Tufts.

Not one to forgive and forget, Barnum turned his back on the Smithsonian. He instead sent the elephant skeleton to New York, where it was displayed inside the American Museum of Natural History.

Weird superstitions and associations

This tale gets grimmer by turns: once the skin of Jumbo arrived at Tufts — where it was displayed inside the newly established Barnum Museum — a set of weird traditions began to spring up around it. For example, people on campus started to drop coins into his trunk, or they might tug his tail. These acts were said to provide an upturn in fortunes.

The cult of Jumbo extended into other, broader parts of university life, too. The athletics team came to be known as “Jumbos,” while the same can be said for its graduates. Archivist Sauer described herself to The Guardian as “a double Jumbo,” as she had received two degrees from Tufts.

Saved from the flames

The habit of pulling on Jumbo’s tail, in the end, eventually led it to completely break apart! Weirdly, this objectively distasteful episode did finally have a vaguely positive outcome. A fire broke out at the Barnum Museum in 1975 but, because of the damage it had sustained, the tail was no longer held there.

That meant it wasn’t caught up in the inferno. On the other hand, maybe it would have been best for the tail to have been destroyed? That way, it would no longer be subjected to these odd human traditions.

New superstitious strangeness

Or so you’d think: yet even after the fire had destroyed so much, new superstitious strangeness still managed to materialize. Someone from the athletics department at the university arranged for someone working in maintenance to go into the burnt museum to gather the ash where Jumbo’s remains had once stood.

This jar of ash has come to be almost an object of worship for Tufts athletes, who turned to it for focus. Unless there have been any changes in recent years, the jar should still be held in the director of athletics’ office today. Poor Jumbo’s cult very much lives on.

Bits of Jumbo

According to Sauer, other parts of Jumbo are still based at Tufts. There are, supposedly, bits of skin there, a whisker, and bits of his trunk. In theory, it should be pretty easy to prove that these items did, indeed, come from Jumbo, as they could be DNA-tested and compared with his skeleton, which stands in the American Museum of Natural History.

When speaking with The Guardian, Sauer seemed to be genuinely excited by the prospect of learning whether these things really did come from Jumbo. Seemingly without irony, she remarked, “Wouldn’t it be great to confirm for sure that all of these are from Jumbo?”

Still in demand

Jumbo has been dead for so long now, yet people really do seem to have retained this morbid fascination with him. While the remnants of his body are generally no longer on display at Tufts, they are fairly easy to access.

All you need to do, iut seems, is ask, and the tail, in particular, is of special interest. “It is so frequently requested we keep it in easy reach,” Sauer revealed. “Amazingly people do ask to touch it.”

Taking “souvenirs”

Even today not all parts of Jumbo’s body are accounted for. We know Tufts and the Museum of Natural History are in possession of large parts of him, but there could well be other pieces scattered around elsewhere. And the reason for that, like so much of this tragic tale, is pretty grim.

In the immediate aftermath of the elephant’s death, a crowd had quickly gathered around the body. And, according to reports, people quickly got to work gathering “souvenirs.” In other words, they had hacked off bits and pieces of the creature for themselves.

A sad life

All in all, today the story of Jumbo just seems horribly sad. His young life was blighted by the death of his mother at the hands of hunters, he was then condemned to captivity, before being sent around the world and put on display as a sort of trophy.

To top it all off, his unfortunate existence ended in a freak accident and his remains were ripped apart and shown off like toys. All of this was in the name of making money for humans.

Changed attitudes

Attitudes towards animals have changed in recent years, so you’d hope a story like this would never again be allowed to happen. Obviously the way humans treat different creatures nowadays can still be awful, but the downright craziness of what happened to Jumbo should, hopefully, never be repeated.

Zoos are now regulated, and nowadays such institutions tend to have more of an emphasis on research and conservation. But the story of Jumbo should serve to remind us that we need to always hold these institutions to account: we’ve witnessed the cruel excesses that can occur if we don’t.