Lexington has one of the most important houses in U.S. architectural history. It could be yours. | Opinion

In 1987, a fire consumed an old house on Grosvenor Avenue that like many in Lexington had been carved into a warren of student apartments.

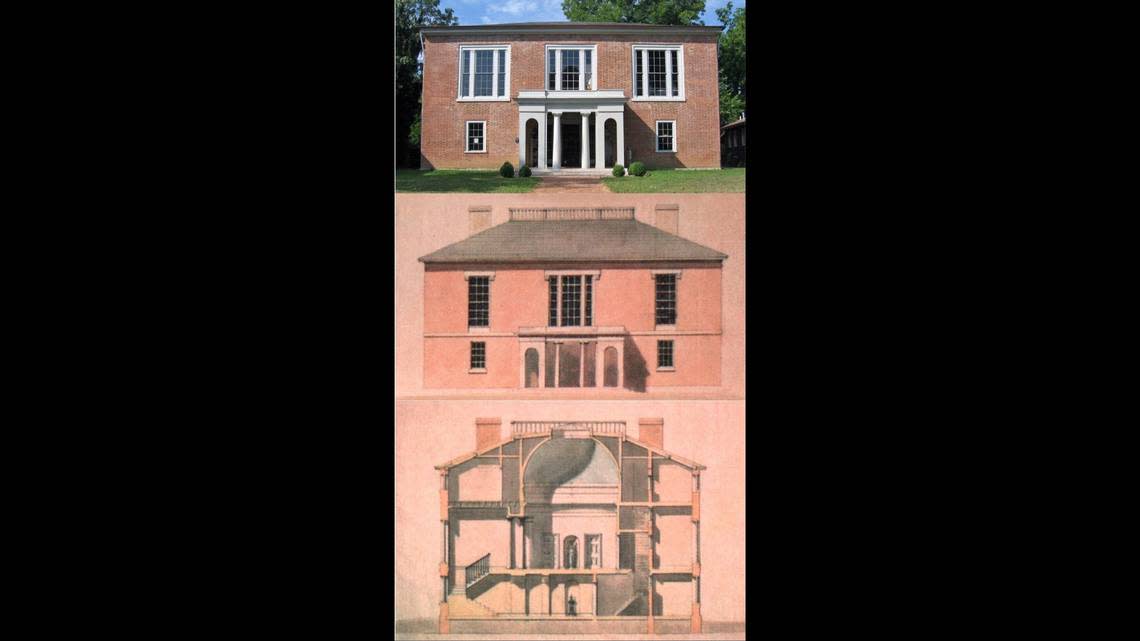

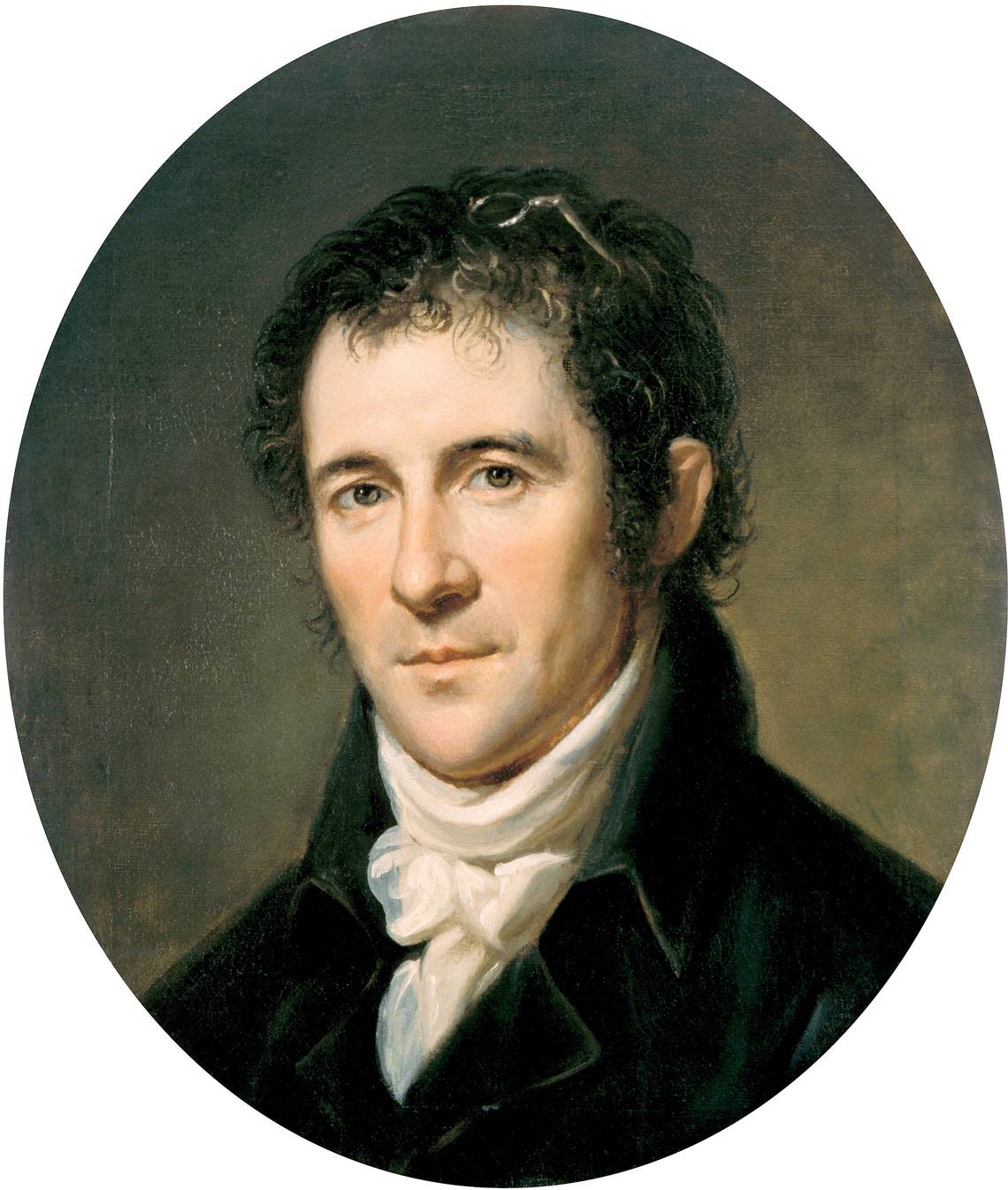

The house was a shambles, but the destruction proved what many had suspected: Underneath the new doors and tiny rooms was a masterpiece residence designed by America’s first architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who also designed much of the U.S. Capitol.

The Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation bought the ruin and began to uncover what many architectural historians consider a radical and revolutionary house first built in 1811 for U.S. Sen. John Pope and his wife, Eliza. It’s one of three surviving houses designed by Latrobe in the country; he had eight commissioned projects in Kentucky, five of which were built.

Pope Villa is the only one left in the state.

The Blue Grass Trust stablized the Pope Villa with a new roof, and along with numerous experts, embarked on a nearly 40-year research project, studying everything from Pope’s theories of domestic architecture to 19th-century wallpaper design. The grand second-story interior rotunda and oculus skylight emerged, along with two curved drawing rooms.

Architectural historian Patrick Snadon, who co-wrote “The Domestic Architecture of Benjamin Henry Latrobe,” called the house one of the most important buildings in Federal America, one “in which he aimed to create a new American house type and show the world how the citizens of a new, democratic Republic might live. It is, in this respect, a building of international significance.”

But four decades later, the Trust has not been able to completely restore the house or ensure it survives into the future. And so, it has recently announced a novel approach to do both: The group has released a Request for Expressions of Interest for people or groups to buy the house.

“The most endangered building in the world is one without a purpose,” said the Trust’s Executive Director Jonathan Coleman. “We are looking for someone who has the resources to restore it and has a plan for its long-term feasibility.”

Restore and reuse

The house comes with a gift: A $748,000 matching grant from Save America’s Treasures IF the new owners can raise the matching amount. That might be enough to build a new roof and basically stabilize the house, Coleman estimates. It will probably take as much as another $2 million to recreate Pope’s original design.

The trust is open to a long-term lease, but it will add easements to ensure the preservation of the original design. It will also require new owners to provide plans for some public access.

“The Blue Grass Trust has stewarded this property for more than 40 years, and it might be the most studied house in Kentucky,” Coleman said. “But our focus is one advocacy, resources and education on historic preservation. We don’t have the resources to restore this house.”

It’s possible that a (very wealthy) person (maybe a new basketball coach looking for a special namesake home?) might be interested in restoring the house to live in, Coleman said. But more likely it would be a commercial or nonprofit use, such as an event space or some kind of well-endowed museum.

Whoever it is will have to meet a high bar to satisfy the trust before any deal moves forward. The Trust will add easements to ensure that any new owner will restore the house properly back to most of its original design.

The University of Kentucky, which is only about a block away from the site, might seem like a good suitor for the match. But Dan Vivian, a historic preservation professor at UK who is the current vice-president the Blue Grass Trust, said he’s heard of no interest in UK taking on another costly construction project.

“This is the most promising way to try to try to protect the building and find an appropriate use and secure its future,” Vivian said. “We’re a relatively small nonprofit with limited finances — most of the possibilities to save the house are nonstarters that haven’t gone very far.”

Not everyone agrees. Dan Rowland is a UK history professor who has been involved with the Pope Villa since the Blue Grass Trust acquired it in 1987.

“It’s always been a very uncomfortable fit for the Trust, kind of like an unwanted stepchild,” he said. “The Trust has always been afraid of it for good reason because the kind of restoration we’re talking about — the scale and expense — they rightly perceive it would suck a lot of oxygen out of other projects.”

He hopes to start a separate nonprofit to raise the matching funds, restore the house and keep it as a kind of learning laboratory.

“The sticking point for me is really public access,” Rowland said.

Coleman said he’s already talked to a few interested parties. The deadline for the expressions of interest is June 30.

The Trust got a thumbs-up from Craig Potts of the Kentucky Heritage Council.

“We’re proud to partner with and support the efforts of the Blue Grass Trust to find creative solutions to full repair and reuse this irreplaceable cultural resource,” he said.