Leroy Hood Wants To Show You How To Live for a Really, Really Long Time

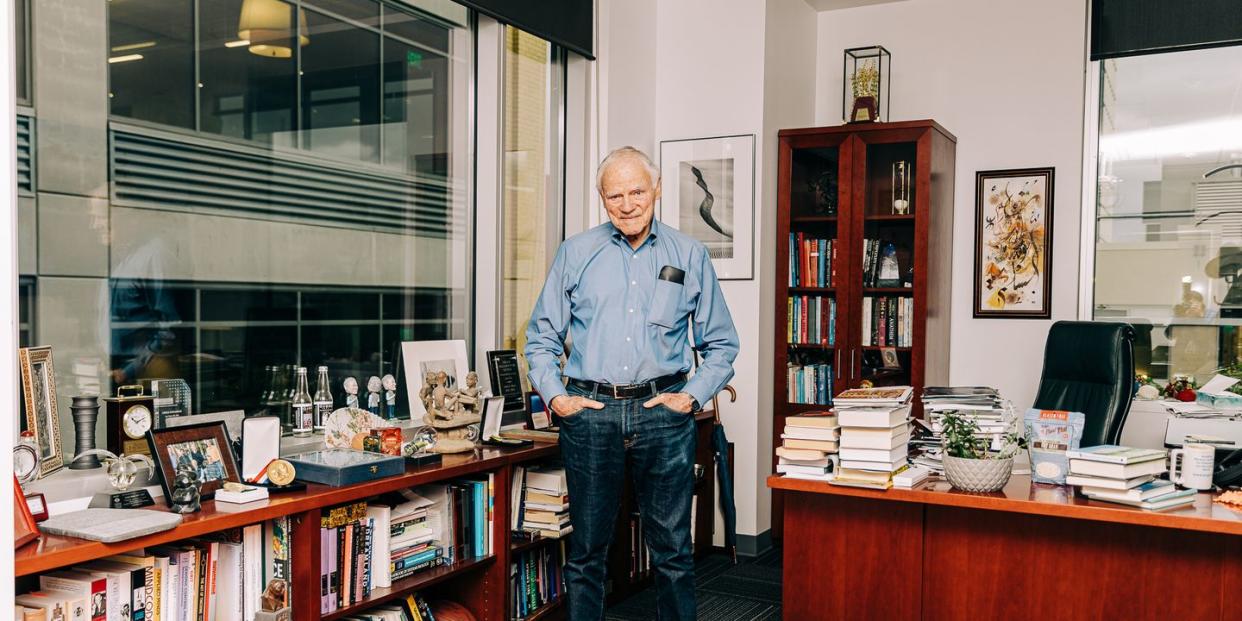

Every morning, Leroy Hood—who goes by Lee—wakes up around 5:30 a.m. He spends the first two hours of his day at his desk—writing, catching up with colleagues, strategizing his next big project. Then he begins his 40-minute workout routine: 200 push-ups, 100 sit-ups, 100 deep-knee bends, followed by a series of stretches and balance exercises. He takes 25 supplements, like vitamins C and D, zinc, and magnesium, and skips breakfast as part of an intermittent-fasting routine. After that, he walks about a mile to his office in Seattle.

Hood, who is 84, is at the forefront of a movement to overhaul healthcare. Technically speaking, he is the cofounder of the Institute of Systems Biology (ISB), a biomedical research group, and the CEO of Phenome Health, a health-technology nonprofit. But what he really is, above all else, is a man with a mission. Hood spends his days on calls with scientists, senators, philanthropists, and tech giants, trying to transform healthcare systems across the globe by making them better at preventing diseases, rather than reacting to them. That way, we can all live a little longer.

When he returns from work, Hood pursues one of his many hobbies. He reads roughly a book a week, an eclectic mix of spy novels, Westerns, and of course, the latest nonfiction on how to live to be 100. He plays folk music on his recorder and takes long, meandering hikes. At 7 p.m. he eats dinner—usually a wholesome combination of leafy greens, whole grains, and fresh fruit—with his partner, Becky, then goes to sleep around 10:30. Then the cycle repeats.

Over the past decade of living by a philosophy of disease prevention, Hood has lost 25 pounds. “I feel as good as I did 20 years ago,” he says over a Zoom call. He is a lean man with gleaming eyes and a child-like grin. He wears a Fitbit on his right wrist and a thick black Oura Ring on his left ring finger that monitors the quality of his sleep. At least twice a year, he gets blood tests from his physicians to monitor his levels of cholesterol, vitamin B12, vitamin B9, lipid profile, and markers of inflammation.

This routine, he is convinced, will help him live a longer and healthier life. He has no illusions about death—he knows it’s inevitable. But he also sees aging as a terrible predicament where our bones become frail, chronic diseases emerge, and our brains slowly turn to mush. Modern medicine, he says, has granted us the tools and information we need to make decisions that can help delay this process for years, or even decades.

At the heart of everything wrong with our current healthcare systems, Hood believes, lies a single question: If we knew what diseases we were at risk for, what choices would we make? He wonders if anything could have helped his wife. Valerie Logan was an energetic woman who loved to rock climb and mountaineer. She led school programs for children and promoted science education. Around 2004, Hood began to notice that Valerie’s mind was slipping. She would forget what she had planned for dinner or struggle to recall her granddaughters’ names. She used to speak eagerly about moving away from their lakeside home in Washington, and then suddenly found the process impossible to manage. Sixty-seven years old at the time, it didn’t seem particularly unusual—they were both aging, after all. But a year later, Valerie was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, a condition with no cure that leads to the progressive degradation of brain cells, causing the loss of memory and basic functions.

Her condition steadily deteriorated. Unable to keep up with the reading pace at her book club, she stopped attending. She quit playing games with old friends. She got lost on walks. A series of fender benders led Hood to take her car keys away. By 2015, 10 years after her diagnosis, it became clear that Valerie needed 24-hour support. At one point she lost the ability to speak, and it was unclear if she recognized anyone who visited her. She was later admitted to hospice care.

Modern healthcare, as Hood sees it, is reactive when it should be preventive. If a person gets sick, they go to a doctor and get treatment. If the treatment works, they will get better—but damage may have already been done in waiting. If things don’t get better, their condition worsens and other associated diseases may emerge.

Hood—who is best known for inventing revolutionary biological instruments that paved way for the Human Genome Project and pioneering systems biology, an all-encompassing approach to science—feels uniquely qualified to captain a movement toward a new, wellness-driven health system.

Incurable, debilitating disease is an outcome that Hood has grown determined to avert. He’s turned himself into a kind of guinea pig for longevity. Some of his habits are pure orthodox: He believes exercise has helped him live long and stay sharp. (It was an easy and familiar habit for the high school quarterback who climbed Yosemite’s El Capitan in his youth.) But he also regularly screens his body for toxins like mercury and lead. He takes drugs like NAD+, which has been shown to slow aging in animals, but is still considered unproven. As he puts it: “I am a living experiment.”

Hood believes that we need a global healthcare revolution. “What I’d like to do is basically convert healthcare from a disease-driven entity,” he says, “to a wellness- and prevention-driven entity.” And he’s confident that innovations in engineering, biology, and data science have equipped us to do that by making much more sophisticated predictions with better opportunities for intervention.

Together with his team, Hood has devised a model called P4 medicine: predictive, preventive, personalized, and participatory. The objective is to provide custom lifestyle plans based on disease predictions—no more waiting around for a diagnosis and reacting accordingly. Instead, Hood hopes for P4-driven policy changes so the world can orient around prevention and wellness. It’s the version of health that he’s been working toward his whole life.

Hood grew up in a small house at the foot of Mount Jumbo, in Missoula, Montana, with three siblings. When he was 6 years old, his brother, Glenn, was born with Down Syndrome. Hood probed his parents and the doctor about what might have caused the condition, but “no one had the faintest idea,” he says. “I couldn’t believe that they couldn’t explain a phenomenon that had had such a profound impact.”

Scientists announced their discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953, when Hood was a teenager. As he read about it in science magazines and books, he realized that understanding DNA could unlock the key to his long-standing questions about Down Syndrome. “It was the center of biology,” he said, “and I decided there, this was something I really wanted to get into.”

He left Missoula to attend college and lived a kind of intellectual paradise in his early adulthood, filled with prestigious universities (the California Institute of Technology for his undergraduate and doctorate degrees, Johns Hopkins for his MD) and Nobel laureates (Richard Feynman, Linus Pauling). In 1967, he joined the National Institutes of Health as an independent researcher in immunology. There, he met with fellow scientists, including Anthony Fauci, in a tight-knit weekly club. “He just stood out among the group,” Fauci says, “as the guy who was whip-smart, intelligent, and very probing and inquisitive.” Hood’s interest in the relationship between health, disease, and DNA strengthened throughout these years, but it grew in tandem with his disillusionment with the way that science was practiced.

Citing a Buddhist parable, he likens science in those days to six blind men, each touching different parts of an elephant, and coming up with totally different theories about what they were feeling. Science, he believed, needed to be integrated.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, as a professor at Caltech, Hood built an interdisciplinary team of scientists with prolific output. They built a protein sequencer, which allowed scientists to detect the sequence of amino acids, the molecules that combine to form proteins; a DNA synthesizer that could join base pairs to form new strands of DNA; a peptide synthesizer to combine amino acids into longer chains; and an instrument that enabled scientists to read out the order of DNA letters thousands of times faster than anything that existed before it. All of these inventions paved the way for the Human Genome Project. “There are people in this country who clearly deserve a Nobel Prize but who didn’t get it,” Fauci says. “I think Lee is really somebody who clearly deserves getting the Nobel Prize.”

Hood wondered, however, what all that work meant if it was locked in university labs, away from the public, for further innovation. So he left Caltech—whose president told Hood that commercializing his inventions was anathema to the role of academia—for the University of Washington to start the first-ever cross-disciplinary biology department. After eight years, he realized that he needed more computers, more brilliant scientists, and above all, less bureaucracy. In 2000, he set up his own research organization, the Institute of Systems Biology.

At ISB, he got to work on solving what he sees as “sickcare,” with the aim of moving the country toward true “healthcare.” Achieving this, however, is no small feat: It requires being able to reliably predict and identify a potential disease before it strikes. And to do that, he says, requires data—lots of it.

Over the past five years, Hood and his team have been conducting a series of data-driven experiments to validate his P4 model. They are tracking the personal data that up to 5,000 patients provide—including genome sequence, gut microbiome, blood plasma proteins, and lifestyle information—for up to four years. The goal is to understand how these data points interrelate and determine the diseases to which each individual might be most prone. Then, they use that information to assess the efficacy of having each participant work with a coach who provides personalized lifestyle advice on matters like nutrition, exercise, and stress management. It’s an effort to improve wellness and avoid the diseases to which participants may be prone.

Overall, the studies found that most participants responded to health advice from coaches, and were able to make significant positive changes. Some of these changes involve relatively trivial lifestyle adjustments: regular exercise, taking vitamin D or magnesium supplements to balance deficiencies. But others are far more invasive—and have radically transformed participants’ lives. In one case, Hood says they found that a patient thought to be suffering from arthritis was actually in their early stages of hemochromatosis, a genetic disorder that results in elevated iron levels in the blood that can prove deadly if untreated. The solution was simple: The patient got blood drawn once a month until his iron levels stabilized.

In another, they found that a patient had exceptionally high levels of cortisol, a stress hormone, but didn’t feel anything other than a minor stomach irritation. She was sent to a physician to do a checkup, including a colonoscopy. The physician found a giant tumor in her colon, which they were able to cut out. “If she had gone home and forgotten about this nonsense,” says Hood, “she’d be dead today.”

Crucially, the study also found that participants were willing to share their data. It may not be too surprising. After all, Hood argues, the big-data model has already crept into our daily lives: Fitbit, Oura Ring, the Apple Watch. But what he has in mind for the world is a version of this on steroids.

Hood imagines creating data clouds that include vast troves of personal health information: entire genome sequences, blood, saliva, stool, urine, molecules produced by your metabolism, proteins, and brain-related biological markers. How this information would be collected is still unclear, but Hood says it would involve using a constellation of apps and other technologies that measure brain signals, blood plasma, sleep quality, blood pressure, and more. Ultimately, Hood hopes that people will be able to—and will want to—do this all from the comfort of their home.

Hood's two children have been tested for genes that increase the risk of Alzheimer’s. His son, who is in his early 50s, is at extreme risk. He follows a personalized program inspired by a book a former student of his father’s wrote, The End of Alzheimer’s, and has eliminated gluten and sugar from his diet and takes supplements to balance chemicals in his blood. The book, which a prominent science journal criticized for using questionable methods based on limited scientific evidence, claims that these steps could possibly prevent or even reverse cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease.

This is what Hood hopes for the rest of the world: a strong data-oriented approach to personal health by monitoring how basic features of your body, including hormones, and vitamin and toxin levels, are changing over time.

Hood is growing his experiment with P4 and Phenome Health to a far greater magnitude with the Beyond Human Genome Project, a new initiative to collect extensive data points from 1 million people over the course of 10 years. The goal is to conduct an all-encompassing analysis of subjects’ biological and genetic makeup to then provide them with personalized instructions on what they can do to live a longer and healthier life. Hood is already in conversation with multiple tech giants, including Alphabet (Google’s parent company) and Microsoft, to help analyze what would be an enormous amount of data.

But his big-data approach hasn’t gone without controversy. Some researchers are concerned about privacy. “What is actually proposed here is to make these ‘holistic datasets’ about you and model them into this avatar—this digital twin or representation of you as a person,” says Henrik Vogt, MD, PhD, an associate professor in community medicine and global health at the University of Oslo. If such information leaked to insurance companies, employers, or other stakeholders who may have a significant interest in obtaining personal health data for profit, he says, it would be a serious compromise of our most intimate information. Others say personalized medicine fails to solve for the root of health issues. “It doesn’t matter how good we are at precision treatment,” says Sandro Galea, MD, MPH, DrPH, an epidemiologist at Boston University. “Unless we actually are creating conditions for people not to get sick to begin with—housing, food, education—we are going to continue having an unhealthy society.”

Hood waves off these criticisms as misunderstandings or trivialities. Privacy concerns, for instance, can be appeased when considering that all personal data would be unidentifiable and highly secured, he says. He likens this to the Human Genome Project, in which the information is free and publicly accessible, but impossible to trace back to any individual. Yet he also can’t fully explain how the personal data would be secured if all this information was collected by apps and instruments owned by private entities. “Look, if you don’t want to do it, you don’t want to do it,” he says.

For his revolution to succeed, people must join in. Hood knows this—participation is the fourth P in P4. In his view, if people don’t want to share their data, they’re losing out. “Anybody who says lots of measurements is bad for learning about wellness and complexity of human beings,” he says, “I would argue is an idiot.”

In the world in which Hood’s ambition is realized, we will all have customized guidelines for healthier living. We’ll know what to eat, how to exercise, what biological markers to look out for, and how to respond when something looks amiss. And perhaps most important, Hood’s world is one in which we’ll actually do it. We won’t put exercise on the back burner; we’ll eat our vegetables; we’ll get our checkups. And we’ll do it because we’ll know for certain that healthy longevity isn’t just an ideal—it’s achievable.

In Hood’s own life, his experiments have been a success. While he may be nearing his mid-80s, his “biological age”—which is determined by markers that estimate the maturity of biological processes—is about 15 years younger. He believes this can be you, too, but with the nontrivial caveat that you’ll have to share some of your most intimate and sensitive data for it to work. The future, according to Leroy Hood, is up to you.

You Might Also Like