Leonard Taylor is set to be executed by Missouri in 9 days. Will an innocent man die?

Leonard “Raheem” Taylor still has hope that he won’t die on Feb. 7.

He still believes in the justice system that sent him to death row.

“I feel real positive and real prayerful that I will get a stay of execution,” he said.

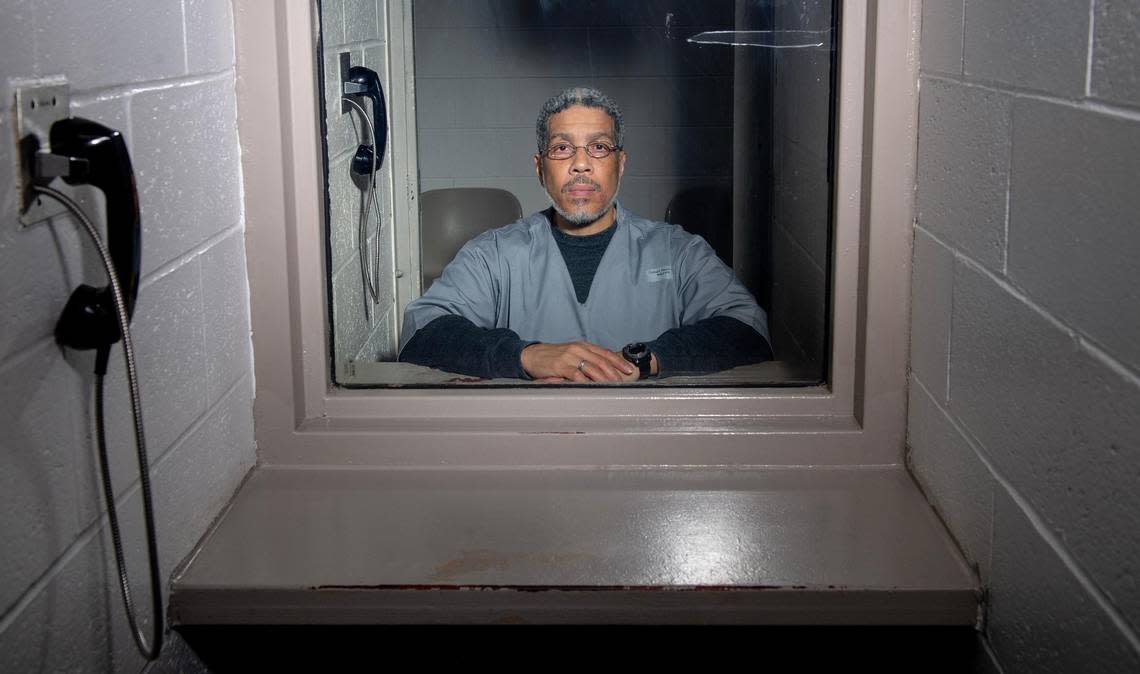

Twenty days before his scheduled execution date, Taylor sat down in a booth in the visitor’s room at a prison in Missouri. At 58, his hair is neatly parted and graying, and he wears silver wire-rimmed glasses. For nearly four hours, he talked about life and his possible upcoming death. Some anecdotes bring out a talkative, lighthearted side. In other moments, he’s solemn or even at a loss for words.

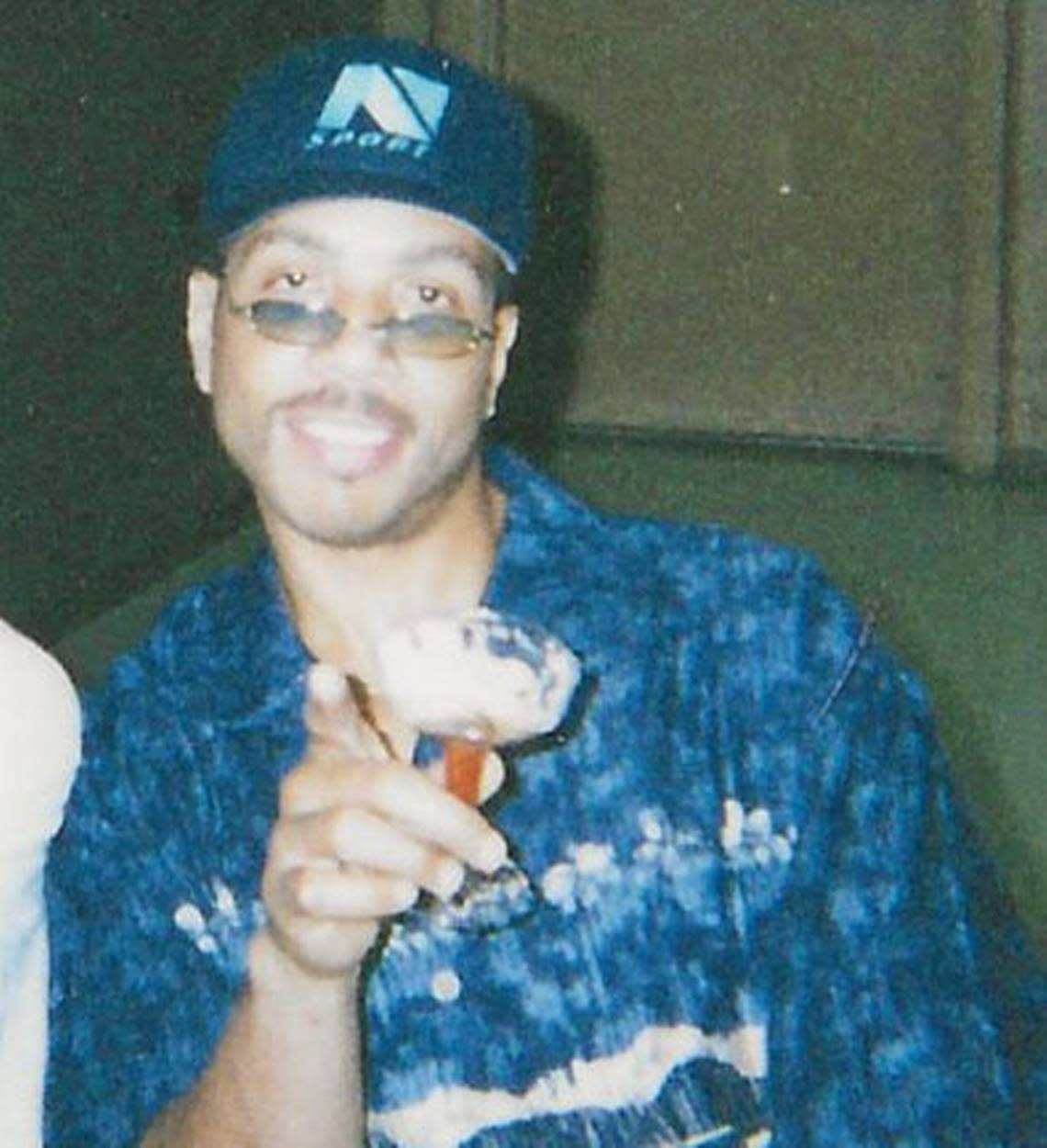

He speaks openly about his years as a drug dealer who made lucrative sums of money trafficking cocaine throughout several states. He vividly recounts scenes from his life, rattling off names, dates and phrases he used to quip: “hit me in the hip” meant someone had paged him; “I’ll see you when I’m looking at you,” he would tell one of his many girlfriends when they asked when he would be back from a drug run. He mischievously smiles at one of the nicknames he would acquire — Cass — short for Casanova.

But he remains steadfast in his claim that he is innocent in the quadruple murder of his girlfriend and her three young children for which he has been imprisoned for nearly 20 years.

Taylor argues he was halfway across the country when they were killed in their home in Jennings, near St. Louis. After prosecutors learned of his “airtight alibi,” he alleges they prodded witnesses to change their testimony about the timing of the homicides, putting him in town.

He was convicted and sentenced to die by lethal injection.

“The biggest thing to be honest with you, emotional thing to me — I never got a chance to grieve for my loved ones,” Taylor said. “I loved Angela and those children. We had a good relationship. I treated the children like they were my own. I couldn’t sit up and say, ‘Man let’s go find out who murdered my family. Let’s go to the funeral. Let me shed some tears for them and say some words during the service and everything and state what a beautiful woman she was.’”

His case is under review by prosecutors in St. Louis County’s conviction unit, according to Chris King, a spokesman for the office. Prosecutors could file a motion for a hearing on his innocence claims, though there are just seven days the courts are open before the scheduled execution. A separate request sent by his attorneys Thursday to the prosecutor’s office asks that a special master be appointed to review the innocence claim.

Taylor has also submitted a clemency request to Gov. Mike Parson’s office.

“Governor Parson carefully reviews the specific facts and circumstances of each case to determine if clemency is appropriate,” said Kelli Jones, a spokeswoman for his office. “Governor Parson will examine Taylor’s application and announce his decision when this review is complete, as has been practice in other capital cases.”

Even if his life is spared, Taylor would remain in prison serving out a sentence on an unrelated rape case.

Several family members of the murder victims believe he was the perpetrator and want the execution to go forward.

But Kent Gipson, one of Taylor’s attorneys, said Taylor has a compelling case.

In addition to Taylor’s alibi, his attorneys say police failed to investigate other suspects including gang members who were after Taylor following a botched drug deal.

“I think the prosecutor certainly has plenty of grounds to give him a hearing to prove his innocence and that’s all we’re really asking for at this time,” Gipson said.

Michelle Smith, co-director of Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, said Taylor’s case is one of many that exemplify why capital punishment should not be used.

“Innocent people are wrongfully convicted and innocent people are executed,” Smith said. “Our system is not perfect. It’s not foolproof.”

Four people have been exonerated from Missouri’s death row since 1999, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Eighteen prisoners remain on death row, including Marcellus Williams, who was granted a stay in 2017 after DNA testing on the murder weapon revealed he was not a match.

While Taylor remains optimistic, Smith said the situation was “very dire.”

“We understand where we are — we are in Missouri.”

Should Taylor’s execution go forward, he will be the third person the state has put to death in just over two months. Kevin Johnson, a St. Louis area man convicted of killing a police officer, was executed Nov. 29. Amber McLaughlin was the first transgender woman to be executed in the U.S. She died Jan. 3.

Both had asked Parson to halt their executions. He chose not to intervene. Though the death penalty is in decline across most of the country, Missouri is one of five states that have executions scheduled this year.

Early years

The first two decades of Taylor’s life did not point to a career in the criminal underworld.

He said he had “a good upbringing.”

Taylor’s father was a veteran who worked at the post office and then established a barbershop. He was also an active member of the Black liberation movement in St. Louis. His mother was loving.

“We played Scrabble and Monopoly and stuff like that,” Taylor recalled. “She raised us real well.”

They had encyclopedias at home and he was fond of participating in Boy Scouts. He looked up to the troop leader, who looked just like the singer Teddy Pendergrass, and got to camp, swim and rock climb.

Taylor, the middle of five children, was 7 when his parents separated. Sometimes things were difficult for his mother who now found herself a single mom, but her faith as a Jehovah’s Witness helped them get through.

His grandmother warned him against reefer, saying it was a gateway drug, and other family members told him “dope is for dopes.” Taylor said he was “pretty much square.”

After graduating from Soldan High School, Taylor joined the Army and then the Reserves for six years, becoming a light-wheel mechanic and generator repair expert.

Back in Missouri, he worked security and managed the Popeyes on Natural Bridge Avenue in St. Louis. One day a young woman came in to buy some chicken. They started flirting, exchanged numbers and fell in love. When he was 22, they moved with their daughter to San Bernardino, California.

His path would take a dramatic — and sometimes dangerous — turn.

The drug game

It was the mid-1980s, at the height of the crack epidemic.

Occasionally, Taylor spent time with a cousin who he described as a “functioning drug addict.” She smoked primos (cocaine and weed mixed together), but he never partook.

“I’ve never gotten high myself,” he said. “I’ve never smoked a joint in my life, never smoked cigarettes, never used cocaine, heroin. The only thing I’ve ever used as far as a substance goes, of course when I was in the military, we’d drink.”

Taylor remembers the day he found out that, even if he didn’t use drugs, he had a knack for selling them.

He was hanging out with his cousin and told her she could break the drugs into smaller portions which could make more money.

She didn’t take him up on the suggestion so he took it upon himself. He bought $140 worth of crack from a drug dealer in the four-plex where she lived and cut it up. He gave it to his cousin’s fiance to sell and made $280.

It happened to be payday for many and it was “like rush hour at McDonald’s.” Taylor kept “re-upping” with his new partners.

He ignored calls from his job at a distribution center asking why he hadn’t shown up.

When he went home, he tossed about $3,000 on the bed. His wife asked where he’d gotten all the cash.

“I said, ‘The only job I’m working from now on.’ That began my life of drug dealing.”

At age 24, he was buying three or four ounces at a time. That turned into a kilo, then kilos.

His wife didn’t agree with his new profession.

Taylor said she would tell him, “Hey, you know what that’s going to bring — that’s going to bring either death or the penitentiary.”

But he continued, dealing with the collateral that can come with selling drugs: rivalries, watching your back and even shootouts.

One day, he got a message on his pager. Another cousin was in town and told Taylor the drug trade in St. Louis was booming to the tune of $28,000 for a kilo, much more than what it was going for in in southern California.

Taylor was incredulous at first. But it checked out.

“I started bringing keys (kilos) of coke back, started off with one, two keys at a time, then escalated,” he said. “I closed my rock houses down in California. Now I’m transporting dope cross country and I was pretty good at it.”

He expanded his network, making connections in Chicago and the south and bringing in large sums of money, enough to support his children and buy several houses across the country.

“I had a taste of the good life,” he said. “I’ve always said that I wasn’t going to be the type of person to say ‘Well, I’ll wait till I retire at 65 or 70 and then I’ll start living.’ No, you’re dying then.”

Taylor regularly made drug runs, staying with one of his girlfriends in whatever city he was in, from Washington to Kentucky. Though still married to his wife in California, they “didn’t have a traditional marriage.” He was living large.

Until Feb. 13, 1991.

When the feds kicked in his door, they found drugs, guns and money.

Taylor went to federal lockup for seven years. During that time, he earned a paralegal certificate. He also “hooked up with some cats that were on some corporate stuff, doing corporate check fraud.”

In 1998, he was released and started down a road of white collar crime. He formed corporations and after receiving real checks, would “jump it up,” increasing the amount of money to cash.

One day, he reconnected with an old neighbor who told him his sister had had a crush on him back in the day.

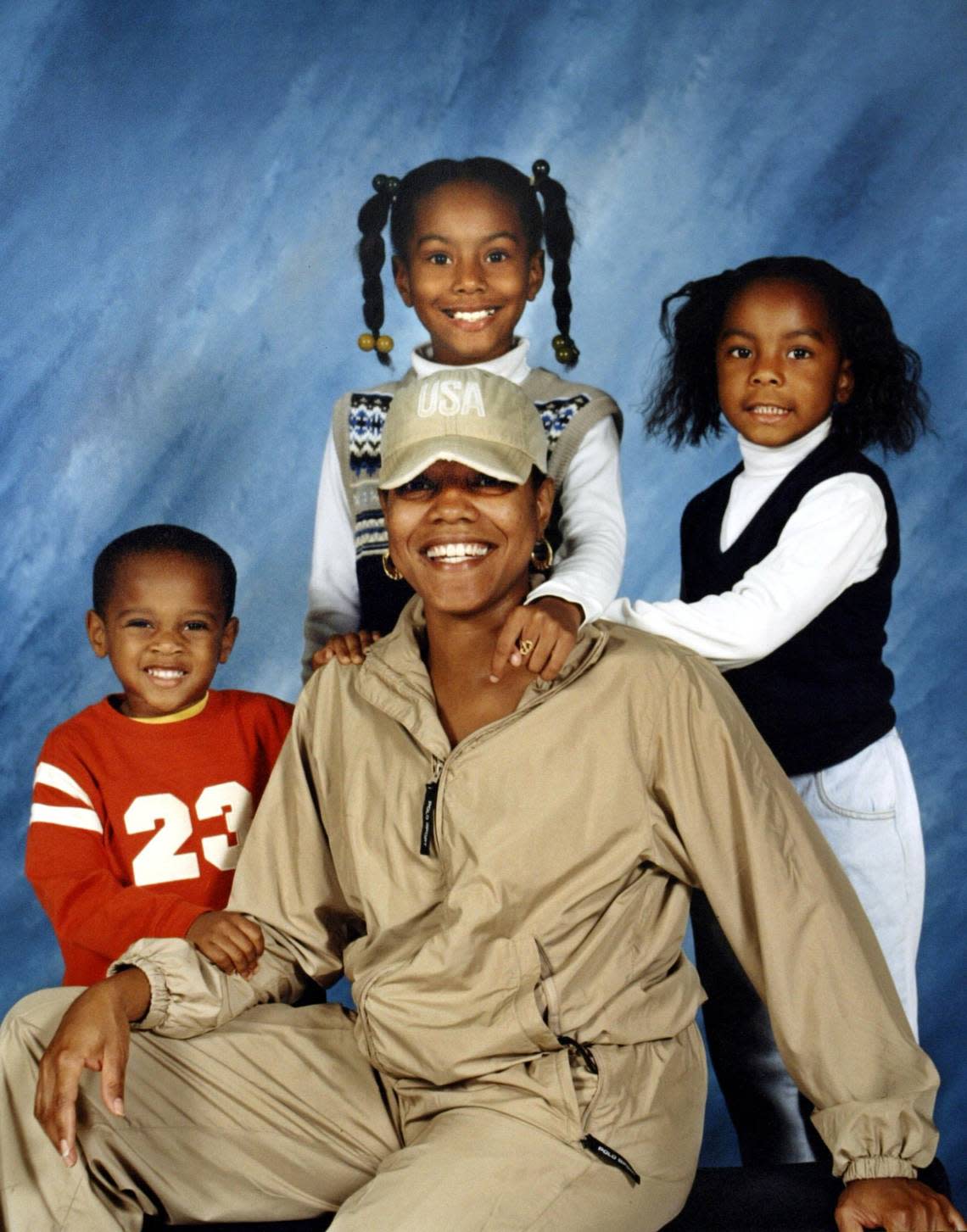

Taylor and Angela Rowe began dating. She was in her mid-20s and had three children.

In 2000, Taylor faced charges after one of his bank accounts was flagged. He was shipped off to state prison and paroled in April 2002. Throughout that time, Rowe visited him.

Upon release, he absconded from a halfway house. He stayed with Rowe when he was in St. Louis and started trafficking drugs again.

In August 2004, they moved into a three-bedroom brick home with a big yard on Park Lane in Jennings, a city on the north end of the St. Louis metro. The kids often played with a neighbor a couple houses down.

Taylor said they relocated there after problems with a relative of the children.

He was also worried about repercussions from a drug deal gone bad.

He had purchased drugs from the Gangster Disciples, a powerful gang operating in St. Louis and several other cities, and they had fronted him a second kilo. The batch was bad but they wanted to be paid for both the kilos, Taylor said.

“It turns into a pretty hostile situation,” he said.

One day, the dispute turned violent when his car was shot at.

Daughter in California

For several years, Taylor had been trying to track down an ex-girlfriend. He asked old associates and even checked the social media site Myspace. He finally got a lead in 2004.

He and Mia Perry had dated a few years starting in the late 1980s. She had two daughters and they settled in Tacoma, Washington. It was a “quiet spot,” he said he would visit to get away from drug dealing.

“Both of my eldest children had called him dad and he was the only real father figure they’ve had,” Perry said in a court declaration.

Taylor said he considered the girls his daughters and not stepchildren because “steps are something you walk on.”

Perry became pregnant with Taylor’s child. But they lost touch after he was incarcerated in 1991. He had only seen a couple baby pictures of his daughter.

In early November 2004, a friend of Taylor’s said he’d found their address in California. Taylor told Rowe he was eager to meet his daughter who was by then 13.

“She (Rowe) knew how bad I wanted to meet my daughter,” said Taylor, a father of six. “I was a hustler, but I always took care of my children. I may not have been around my children all the time to raise them, but I did finance them. I made sure they had the things that they needed as far as clothing and food and shelter.”

On Friday, Nov. 26, 2004, Taylor arrived at the airport in St. Louis carrying two large bags. He went through security, walked to gate 16 and boarded Southwest flight 605.

“They were alive when I left,” he said.

That weekend he met his daughter Deja Taylor.

“They were just happy to see each other,” Perry recalled in a phone interview last week. “And I just thought, wow, what a beautiful day it is.”

That Monday, he hopped on a Greyhound bus with a kilo of coke and headed to Georgia where he had business to do.

Shot execution style

A Jennings police officer was dispatched at 5:32 p.m. on Dec. 3, 2004, to check on a family who lived on Park Lane. There were five yellow-wrapped newspapers in the front yard, an investigative report said.

It had been seven days since Taylor had flown to California.

The officer forced entry through a window.

Rowe was discovered in a bedroom, shot in the left side of her chest and left wrist. Alexus Conley, 10, Acqreya Conley, 6, and Tyrese Conley, 5, were found lying on a bed in a different bedroom. They had also been shot and were in an early state of decomposition, according to an investigation record.

Several agencies responded to the scene, including the Major Case Squad. The St. Louis County medical examiner was called at 6:15 p.m.

Rowe’s sister Gerjuan Rowe identified the victims at the ME’s office at 10:30 that night.

The autopsies initially indicated the homicides had taken place two to three days before the bodies were found. That would have been at least four days after Taylor had left for California.

Taylor was arrested several days later in Kentucky.

An investigator told him, “You’re a person of interest in a quadruple homicide in Jennings. They lay pictures of my girl Angela and the kids out on the table in the house deceased. All of them had been murdered and they was shot execution style.”

He was asked what he knew and said he wanted his lawyer.

“I wanted to prove my innocence,” he said. “I wanted to vindicate myself. I knew that I hadn’t committed these murders. I knew I hadn’t had anything to do with it.”

Eventually Taylor was extradited back to Missouri where he faced a separate rape case in the city of St. Louis.

That allegation initially surfaced in 2000, but he was not charged until his arrest in the 2004 murder case.

Taylor told The Star he did not touch the teenager, who he had been a father figure to. She was mad at him for telling her what to do, namely to stop hanging out with a young dope dealer and improve her grades, he said.

He was convicted in that case and sentenced to 100 years.

The murder trial began Feb. 20, 2008. In the four years since the initial investigation, St. Louis County medical examiner Phillip Burch had changed his conclusions.

Burch told jurors that the temperature in the house had been in the 50s, which led to the estimated time of death changing. The murders could have taken place two to three weeks before the bodies were discovered — when Taylor would still have been in town.

In charging him, investigators had relied on Perry Taylor, Leonard Taylor’s brother, who told police Leonard Taylor had confessed that he had killed Rowe and the kids before leaving for California. But at trial he recanted, and Taylor’s attorneys contended his earlier statement was coerced from him by police.

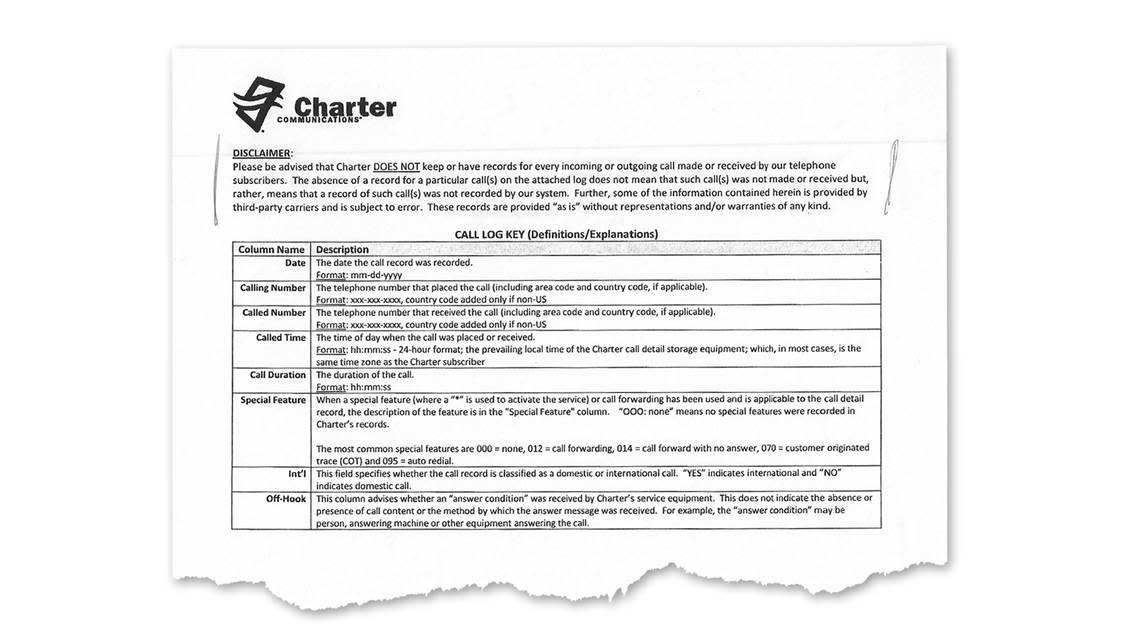

Prosecutors argued that no one had heard from Rowe since Taylor left town. The phone company Charter had records showing no calls were made to or from her home phone after Nov. 24, 2004.

Rowe missed her housekeeping shifts at a local hospital beginning Nov. 26 and the children did not return to school Nov. 29 following Thanksgiving break, according to court documents.

But Taylor’s defense presented evidence that contradicted the timeline: Multiple people — including a neighbor, Rowe’s sister and two aunts of the children — had talked to or seen her or the kids the weekend after Taylor left town. They also contended Taylor had no motive.

A jury returned a guilty verdict and Taylor was condemned to death.

“I couldn’t believe that a jury would even come to the conclusion that I committed these crimes,” he said.

New evidence

Throughout years of appeals, new information has been uncovered.

His attorneys discovered a disclaimer issued by the phone company Charter — which had not been shared with the defense at trial — saying their call records may not be complete. Records from other carriers like Sprint showed calls were made from Rowe’s number to their customers up to Dec. 3, 2004, long after Taylor had flown to the west coast.

In an affidavit signed Wednesday, less than two weeks before the execution date, forensic pathologist Jane Turner cast doubt on the medical examiner’s determination on the time of death. There was evidence of rigor mortis when the victims were discovered. That would not last more than a week after death even with the cold temperature in the house, according to Turner. Other postmortem changes that would occur a week or more after death were not present.

That meant the condition of the bodies suggested the victims were killed after Taylor left town.

James Trainum, a policing expert who served with the Washington, D.C., Police Department for 27 years, also reviewed the investigation at the request of Taylor’s attorneys.

He identified “red flags” pertaining to Perry Taylor, who died several years ago. Police believed Perry Taylor knew something about his brother’s involvement in the murders. Perry Taylor was detained three times, twice at gunpoint, in the days after the bodies were found. During the third interrogation, he was taken to the Jennings Police Department, a Major Case Squad report said.

“They would take me out to a car, rehearse the shit that they wanted me to say, and take me back inside and make me say it,” Perry Taylor said in a deposition. “They threatened my life, they threatened my livelihood, they threatened my mother’s life.”

Trainum said the tactics police used “were extremely coercive” and have been known to produce false statements.

Rick Knox, executive director of the Major Case Squad, said any reports would have been handed over to the Jennings Police Department, which no longer exists. That area is now policed by the St. Louis County Police Department, but spokesperson Sgt. Tracy Panus said the department had no comment on the case.

Attorneys also talked to his daughter Deja Taylor. When she met her father for the first time in 2004, she said, he called Rowe. At one point, he handed the phone to her to talk to Rowe.

In a court document, Deja Taylor said, “I spoke with Angela for a few minutes. I also spoke briefly to one of her children although I do not remember her name.”

“My father and Angela told me that they wanted me to come out to St. Louis to meet her and her children in person. I was so happy to connect with my father and his new family that I cried quite a bit that day.”

Mia Perry said she was sitting near her daughter during the phone conversation with Rowe.

“He called her and my daughter spoke to her,” Perry said. “And they talked for quite some time.”

Beverly Conley, an aunt of the children, maintains that she too spoke to Rowe a week before the bodies were found. That would have been after Taylor left for California. But she believes he is guilty.

“I’m just ready for him to get what he deserves,” she said.

Death warrant

Taylor has tried to stay busy throughout his years at Potosi Correctional Center “to take my mind off of things.”

He’s worked a hazmat job, served as president of the NAACP prison chapter and used his skills as a paralegal helping other men on their cases as well as his own.

“Helping others, that has helped me along the way,” he said.

On Oct. 18, 2022, Taylor was heading to the law library when he saw the warden, who was looking for him.

He did not know why.

They went up to his cell.

“He said ‘Listen man, they set a date.’”

Taylor asked, “A date?” He wasn’t sure what they were talking about.

“He said, ‘Yeah, an execution date.’”

“I said, ‘What?’”

The warden repeated himself. The Missouri Supreme Court had issued a warrant of execution for Feb. 7.

Taylor was given the chance to say goodbye to the other men. Several hugged him and he told them, “Listen, just hold my job for me, man.”

Now he is on 24-hour lock down because prisoners with a death warrant are moved to solitary confinement.

Though Taylor seems mostly upbeat, at times he can’t put the feelings he has about his situation into words.

“I can’t even say for real. Sometimes I’m numb about it,” he said. “Some days are better than other days.”

His faith as a Muslim has given him strength. He said he is a “student of life” who has studied many religions and, influenced by his father, ultimately chose Islam as an adult.

The upcoming date has been difficult for Deja Taylor, Perry said.

“It’s like ‘Mom, how do you bring someone in my life just for someone to take them away’? I couldn’t answer that.”

In her court declaration, Deja Taylor said she regularly talks and writes to her dad, who has helped her navigate relationships, career and the death of her grandmother.

“If my father is ever executed, it will be a tremendous blow to me,” she said.

Leonard Taylor said he believes in America and the judicial system. However, he does not believe the death penalty should be allowed.

“I used to think it should (be used) until I was falsely accused and wrongfully convicted,” he said.

Taylor said he wishes Gov. Parson would be able to “look at my case and look at the evidence, and lack of evidence, and you yourself would see that you have an innocent man sitting here on death row, scheduled to be executed.”

Two bills to abolish the death penalty were filed this month in Missouri’s General Assembly. Neither are expected to advance in the overwhelmingly GOP-dominated legislature.