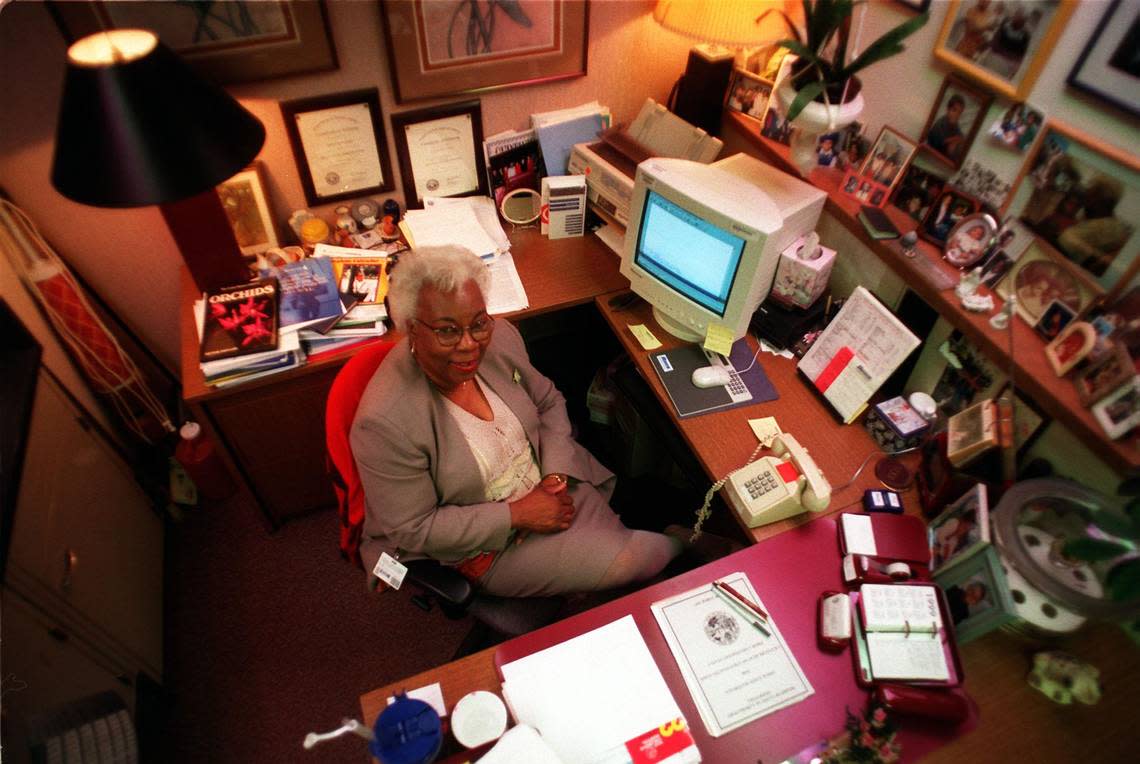

Leona Ferguson Cooper, ‘a junkie for social justice,’ dies at 90 in Coral Gables

Leona Ferguson Cooper once told her friend she was a “junkie for social justice.”

Such an apt description of Cooper, a Coral Gables civic activist who, her friend, Miami Herald columnist Bea Hines, said “supported causes that bridged cultural, racial and religious gaps.”

Cooper, who died at age 90 at her Coral Gables home on Nov. 4, her daughter Clarice Cooper said, did so for decades.

Fellow activists and admirers and even combatants, like developers or city officials who wanted to make over parts of historic Coconut Grove and Coral Gables that would steamroll over the two neighborhoods’ founding Black community and its interests, noticed and respected Cooper.

The pope noticed her and honored her. In December 1992, Pope John Paul II presented Cooper the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice Award after she had founded the St. Martin de Porres Association, a lay group for Black Catholics in the Archdiocese of Miami.

READ MORE: Piece of original Miami endangered: West Coconut Grove’s Black history slipping away

‘Powerful, strong woman’

The Nassau-born Cooper loved her adopted Miami-Dade home, which was also her family’s lifelong home, and her reach was vast.

“She was a powerful and strong woman and at a time when being a powerful and strong Black woman was very challenging — and she did it so well,” said her friend Bonnie Bolton.

Bolton is the daughter of the late Coral Gables activist Roxcy O’Neal Bolton, another inveterate fighter for human rights, who similarly died at age 90, in 2017, after leaving an indelible mark in South Florida.

“She was so fearless and a warrior and Roxcy always thought of Leona as a warrior,” Bonnie Bolton said of Cooper who, by profession, spent more than 40 years in the field of microbiology and medical technology in clinical laboratories at local hospitals until she retired from the Miami Veterans Administration Medical Center as a supervisory microbiologist in 2002.

“She was so accomplished. It’s unusual for someone to be accomplished in the sciences and in the arts but Leona was involved in the arts and religion and science in the community and in civic matters. She just had such a broad range of interest and gave her support in all of those areas and was so well known. She was a very impressive person,” Bolton said.

Roxcy Bolton, a force who was Cooper’s friend and ally in many of her endeavors on behalf of women’s rights, the Black community and crusading for social justice, said of Cooper in a Miami Herald column in 1998: “Leona is a credit to the human race. She cuts to the chase. But she always has an extra moment to give and reach out to make a difference. She’s not a phony.”

‘Not afraid to raise her voice’

Historian Dorothy Jenkins Fields, founder of the Black Archives, History & Research Foundation of South Florida, recalls attending meetings with Cooper in the late 1980s with a group led by Roxcy Bolton. They wanted a woman’s park at 10251 W. Flagler St. in Miami. Fields was impressed with Cooper’s drive, alongside Bolton. Cooper attended County Commission meetings. Wrote letters. Made phone calls. Insisted that community leaders recognize the contributions of diverse women.

“She was not afraid to raise her voice and stand up to make the point,” Fields said. “She often said to me, ‘The time is past due for women and Black people to be included. We helped make this a thriving community.’ With a smile but stern voice it was known that she had done the research and was prepared to help move the project forward.”

In 1992, Bolton’s dream was realized. The Women’s Park was designated as the first known park in the nation dedicated to women, Fields said. The Leona Ferguson Cooper Playground for Children was named to honor Cooper at The Women’s Park in 2007.

READ MORE: Women’s Park in Miami pays tribute to Roxcy Bolton

From Nassau to Miami

Cooper was born Leona Helen Ferguson in Nassau, New Providence, in the Bahamas, on June 30, 1932. She moved to Miami with her mother Helen when she was 14. Cooper graduated from Miami’s Booker T. Washington Junior/Senior High School in 1949.

In January 1950, she married William Alexander Cooper, who was born to Bahamian immigrant parents in his godmother’s front bedroom in Coconut Grove on April 12, 1929. The couple would raise five children together — Clarice, Wilhemina, Leslie, William Paul and Adam. The Coopers became civic leaders while juggling careers and family.

“They always figured that a good citizen had to be somebody who was involved in the game and, also, they cared a lot about the underdog, anybody that was suffering or needed to have advocacy. That was the word I can use to describe them: advocacy. For people who had no representation, they ended up in leadership positions because those are the kind of personalities they had,” said their daughter Clarice Cooper.

Respecting a community

Along with her husband, who died at 79 in 2008, the Coopers spearheaded efforts to save the MacFarlane Homestead neighborhood — also known as the Black Gables, a commonly used descriptor for the area that Cooper despised.

“It’s insulting,” she told the Herald in 2013.

At the time, Cooper was attending Gables Commission meetings to fight developers’ and some Gables officials’ land swap plan to build a trolley depot in the West Grove’s Golden Gate and MacFarlane Homestead Subdivision. Cooper had helped get that area a historic designation in 1993.

Cooper, and many residents, felt the proposed trolley site was an improper use of land and denigrated the Black community. They felt the trolleys would not serve both residents of the Gables and the Grove communities.

Family matriarch

Donald Slesnick, who served as Coral Gables mayor from 2001 to 2011, calls Cooper the “matriarch of a family of doers and a family of people who are committed to their community and keeping it alive and well and improving on it. And while I was mayor, she was one of the most positive people about inputting things to help me understand the needs of that community.”

Cooper and her husband were active in the Lola B. Walker Homeowners Association and the building of its community center at the Bahamian Village. The village was so named as a tribute to the Bahamians who helped develop and build Coral Gables and eventually settled in the city’s MacFarlane Homestead Historic District, east of U.S. 1 and bordered by Grand Avenue and Brooker Street.

The community center finally opened in 2017. Cooper first advocated for that community center in 2000. The Coral Gables Commission had approved of her idea in 2005.

Cooper was the first Bahamian-American member of the Coral Gables Community Foundation, Slesnick said.

A resonant voice

Hines, in one of her columns in the Herald, surmised that Cooper was such a fighter because she had “felt the sting of discrimination, not only as a Black, but also as a woman, and as a Black Catholic.”

In 1969, Cooper led a fight for women to become lay ministers in the Roman Catholic Church. In 1990, she went to Washington to speak against a U.S. Food and Drug Administration policy that had banned Haitian immigrants from donating blood..

In 1986, Cooper founded the St. Martin de Porres Association, an organization committed to improving the status of Black lay Catholics in the Archdiocese of Miami. Cooper believed that many Black Catholics felt their music and their participation in the Archdiocese’s pastoral center was not accepted by the Church.

For her efforts, she was one of 25 South Floridians presented the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice Award from Pope John Paul II.

“Never in my life did I ever expect to receive anything like this,” Cooper, a founder of St. Hugh Catholic Church in Coconut Grove, told the Herald when she received the medal in 1992. “I feel very humble. Now I have to really be a good girl,” she joked.

Her favorite role

This was another trait that Hines, the Herald columnist loved about her friend — her humor.

The two first bonded in the early 1980s when Hines, Cooper and Clarice, who had worked in the Herald’s classified division, sang with the Miami Oratorio Society.

“Right away we clicked. I loved Leona’s sense of humor and her way of making everyone around her feel special,” Hines said.

“In addition to being funny, Leona was also a staunch feminist and fighter for the equal rights of everyone. But with all that she had going on for her, to me her main attribute was her humility. Over the years, I watched as she worked to make her community of Coral Gables more inclusive to its Black residents.

“A founder of St. Hugh Catholic Church [in Coconut Grove], Leona also worked with the local Catholic Church to be more inclusive to Black parishioners. With all her church and civic work, Leona was a devoted wife and mother, a role she loved best.”

Clarice and her siblings were the beneficiaries of that favorite role — a gift Clarice said she came to understand and cherish when she matured.

“She was like any other mother to us. Sometimes there was something that you wanted to do and she’d say no,” Cooper’s daughter said, laughing at the memory. Oh, those “no” decisions felt so difficult. Discipline, what a bother. “Just like any other kid about his or her parents, right?” Clarice said, with another chuckle.

“But as far as strong values, of developing solid citizens and adults and responsible people, I would say most of what I learned was from both parents in that regard,” Clarice said.

Survivors, donations

In addition to her daughter Clarice, Cooper’s survivors include her daughters Wilhemina Cooper, Leslie Cooper and son William Paul Cooper. (She was predeceased by her son Adam and two grandchildren). She’s also survived by her grandchildren Leigh Cooper-Peabody, Carlin, Qianna and Toni Cooper; great-grandsons Austin M. Cooper Jr. and Logan A. Willis; sisters JoAnn Turner, Barbara Ferguson Gatson, Florence Ferguson; and brothers Leon Ferguson Jr. and Johnny Ferguson.

Services were held. Donations in Cooper’s memory can be made to the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America - Miami-Dade County Chapter at 1601 NW 12th Ave. in Miami.

Janet McAliley, School Board trailblazer and ‘very soul of decency,’ dies at 88 in Miami