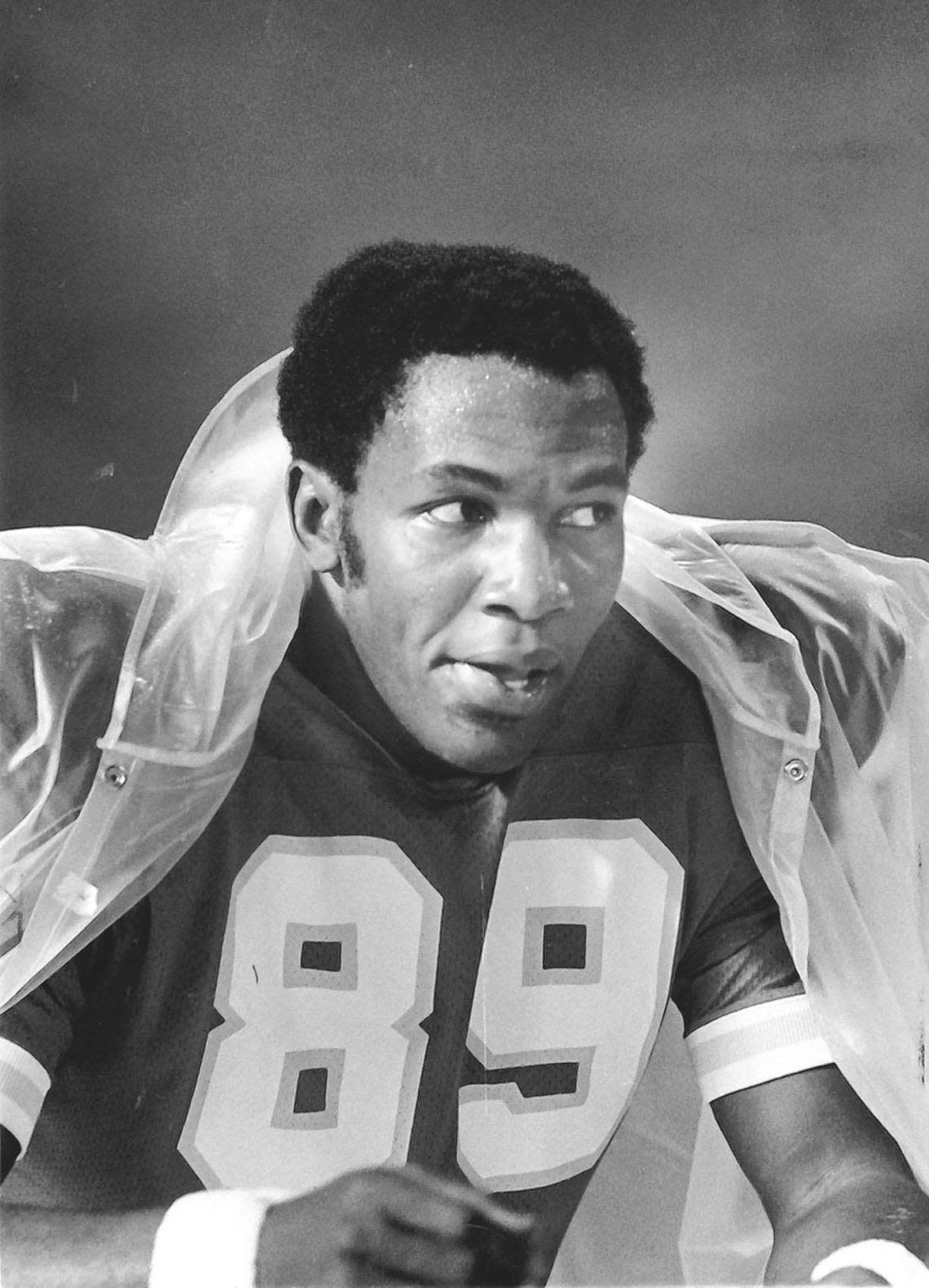

Legendary Kansas City Chiefs receiver Otis Taylor dies at 80: ‘He never let us down’

Otis Taylor, the Kansas City Chiefs’ electrifying, big-play wide receiver during their Super Bowl era of the late 1960s, has died after a lengthy illness. He was 80.

During his 11-year pro career, Taylor was one of the most dazzling offensive players in football. At 6-foot-3, 215 pounds, he was the first of his kind at wide receiver and a prototype for the next generation of receivers. He was a big target with supple hands who had the speed to go deep and was fearless going across the middle.

“When we didn’t know what else to do,” quarterback Len Dawson once said, “Otis would say, ‘Throw the ball to me.’ And he never let us down.”

Taylor, tall and graceful, authored a signature play in Chiefs history when he caught a hitch pass against Minnesota in Super Bowl IV, bowled over a defender and high-stepped down the sideline for a 46-yard touchdown that clinched the 23-7 victory for what is still one of the greatest upsets in pro football history.

Taylor, a three-time Pro Bowler, was voted AFC Player of the Year in 1971 when he was the only receiver in the NFL to post a 1,000-yard season, catching 57 passes for a whopping 19.5-yard average.

Taylor, who played from 1965-75, retired as the franchise record-holder for touchdown receptions with 57; his 410 receptions were a club record until 1986; and his 7,306 yards receiving was a club record until 2005, when Tony Gonzalez eclipsed it. Taylor was inducted into the Chiefs Hall of Fame in 1982.

The only thing missing from Taylor’s glittering resume was election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, an omission some consider glaring. Eight of Taylor’s teammates are enshrined in Canton, Ohio, along with coach Hank Stram, club founder Lamar Hunt and Dawson, who died in August of last year at 87.

Taylor’s most recent and perhaps final chance for election to the Hall of Fame came in July 2022, when he fell short of the votes needed for inclusion as a senior finalist.

Not being part of that group bothered Taylor long after he retired. On the day before former Royals star George Brett was to be inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1999, Taylor expressed happiness for Brett but said, “I sit around sometimes and wonder how it feels. … If you close your eyes and think about something you want to happen, it can happen if only for a second or two.”

It can be argued that Taylor’s candidacy was hurt because his statistics — compiled during 14-game seasons compared to the 16-game schedules (and now 17) played since 1978 — do not stack up well with the receivers in today’s more wide-open game.

But Pittsburgh’s Lynn Swann was voted to the Hall of Fame in 2001 even though he never had a 1,000-yard season and had fewer career catches (336), yards (5,462) and touchdowns (51) than Taylor.

Green Bay Hall of Fame cornerback Herb Adderley, who covered Taylor in Super Bowl I, believed Taylor had Hall of Fame credentials.

“Just from watching film, I knew Otis Taylor was one of the best receivers in the game,” Adderley told The Star in a 1987 interview. “But seeing the guy on film and seeing him in person were two different things. Otis was quicker, faster and bigger than I thought. He was as good as any receiver I ever covered.”

Taylor’s statistics might have paled compared to those of others in the Hall of Fame because the Chiefs played a conservative offense and stressed defense and kicking.

Taylor also played in an era when the bump-and-run defense was in vogue. Cornerbacks were allowed to jam receivers as they ran downfield, and it was legal for linebackers and safeties to smack receivers who came across the middle.

“In today’s game, with today’s rules,” retired Chiefs kicker Jan Stenerud said a few years ago, “Otis would catch 150 passes every year. Who would stop him?”

Taylor, who played at Prairie View A&M (which has retired his No. 17 jersey), was a fourth-round draft choice by the Chiefs in 1965 at the height of the bidding wars for players between the upstart AFL and NFL. The Chiefs had scout Lloyd Wells hide Taylor at a hotel to keep him away from the Eagles until Kansas City could sign him.

It didn’t take long for Taylor to make an impression.

As a rookie in 1965, he played behind Frank Jackson and Chris Burford during the first two weeks of the season, but on his first play from scrimmage in week three against San Diego, a teammate missed an assignment, causing Dawson to be trapped.

Dawson rolled right and found Taylor for a 13-yard touchdown. One play. One catch. Six points.

A career was born.

In 1966, Taylor’s first full season as a starter, he established himself as the game’s most dangerous deep threat. He caught 58 passes for 1,297 yards and eight touchdowns, averaging 22.3 yards per catch. During that season, he caught passes for at least 70 yards four times, including his career-long when Taylor turned a sideline pass into an 89-yard touchdown against Miami, the longest reception in the NFL that year.

And Taylor was at his best in the biggest games. In the Chiefs’ loss to Green Bay in Super Bowl I following the 1965 season, his 31-yard reception against Adderley set up the Chiefs’ only touchdown.

Taylor’s 68-yard catch from deep in Kansas City territory set up the winning touchdown in the Chiefs’ 1969 playoff victory over the Jets; and his acrobatic, over-the-shoulder, sideline grab pulled the Chiefs out of a hole and sent them toward the go-ahead touchdown when the Chiefs beat Oakland in the 1969 AFL Championship Game.

That victory put the Chiefs in Super Bowl IV, where Taylor caught six passes for 81 yards, including the memorable 46-yard touchdown catch and run that is still a staple on NFL Films’ Super Bowl highlight shows.

“People still talk about that catch,” Taylor said recently. “It’s so fresh in people’s memories, like it happened yesterday or last week.”

Two other catches from Taylor’s career stand out.

The first came in 1966 against Boston, when Taylor caught nine passes for 133 yards and two touchdowns. The highlight was a lefthanded stab for an incredible, 26-yard touchdown in a 27-27 tie at Municipal Stadium. While running toward the flag in the right corner of the end zone, Taylor stuck out his left hand and caught a ball that Dawson had intended to throw out of bounds.

“Here I am trying to throw the dang thing out of bounds, and he catches it for a touchdown,” Dawson recalled. “I never said a word. After the game, I told the reporters, ‘That was the only place I could throw it because of the defense.’

“That catch he made was out of this world,” said Patriots coach Mike Holovak. “You can classify him with the greatest.”

Years later, Taylor called it his most difficult catch.

“I didn’t know I’d get it, but I ran as hard as I could, leaped and put up my left hand,” he said. “That’s my job, to catch the ball. I might have made one or two one-hand catches this year before that one. In college I used to make a lot of them, and the coaches were on my back because I didn’t use two hands. But here, my job is to catch the ball, even if I have to use my feet. That’s my job, catching the ball.”

The second memorable catch came in the final moments of a 1971 game against Washington when Taylor caught a game-winning touchdown pass despite having one arm pinned to his body by cornerback Pat Fischer, who had his arms wrapped around Taylor.

Still, Taylor reached up with his right arm and as he crossed the goal line, grabbed Dawson’s pass for a 28-yard touchdown and a 27-20 victory at Municipal Stadium.

“I don’t think I could have been any closer to him than I was,” Fischer said. “I didn’t expect him to catch the ball one-handed.”

Interference had not been called, and Taylor said the next day: “ I didn’t realize until I saw the picture in the paper Monday morning that my left arm wasn’t free.”

Dawson remembered a play just before the touchdown in which he and Taylor converted a third-and-long situation.

“I was looking for somebody downfield, but no one was there, and I was running for my life,” Dawson recalled. “Otis was my outlet man, he was on the sideline just about five yards out. I got the ball to him, and he was hit by four or five players, but he still got the first down. It was the toughest 10-yard run there was. That’s what Otis Taylor is all about.”

One of Taylor’s most memorable moments was not a catch, but a brawl.

During a game against arch rival Oakland on Nov. 1, 1970, Raiders defensive end Ben Davidson speared Dawson after the quarterback gained 19 yards for a first down that would have sealed a key AFC West victory at Municipal Stadium.

Dawson was down at the Oakland 29 with about a minute left and the Chiefs ahead 17-14 when Davidson dived, helmet first, into his back.

Taylor came to the aid of his quarterback and traded punches with Davidson as they tumbled to the ground. A bench-clearing brawl ensued, and once order was restored, the referee called off-setting penalties, nullifying Dawson’s first down and ejected Taylor from the game.

Having to replay the down, the Chiefs failed to pick up the first down, had to punt, and the Raiders drove to the Kansas City 41, setting up a George Blanda field goal. Blanda made the field goal with 8 seconds left for a 17-17 tie, which ultimately cost the Chiefs a tie with the Raiders for the division title.

“They had to blame somebody,” Taylor said the next day. “I wasn’t out to get Davidson. I didn’t know him from anybody else. I just knew somebody had jumped on Lenny, and I was worried that he was hurt.”

By 1974, Taylor was bothered by calcium deposits in his upper right leg, and in 1975, he was active for just one game because of aching knees. Stram had been replaced after the 1975 season by Paul Wiggin, and Taylor was traded to Houston in July 1976 but did not pass a physical.

Taylor later worked 11 years as a scout with the Chiefs with the hope of being a receivers coach one day, but he was dismissed, along with several other members in the personnel department in the spring of 1989 after Carl Peterson became the club’s president/general manager. After leaving the Chiefs, Taylor spent several years working as a community ambassador for Blue Cross and Blue Shield.

But Taylor never stopped being a Chief.

“I had one dream in my adult life, and that was being a coach for the Kansas City Chiefs,” Taylor said on that July 1999 day when Brett was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

“I don’t think they would have fired me if I had been in the Hall of Fame.”

Taylor’s survivors include wife Regina, son Otis Jr. and sister Odell.

Randy Covitz covered the Chiefs and NFL for the Star from 1986-2015.