Lead found in soil at three Durham parks, some at ‘disturbing’ levels. What to know.

Duke University researchers found high levels of lead in the soil at three City of Durham parks, all of which were located near the historic sites of garbage incinerators in the city.

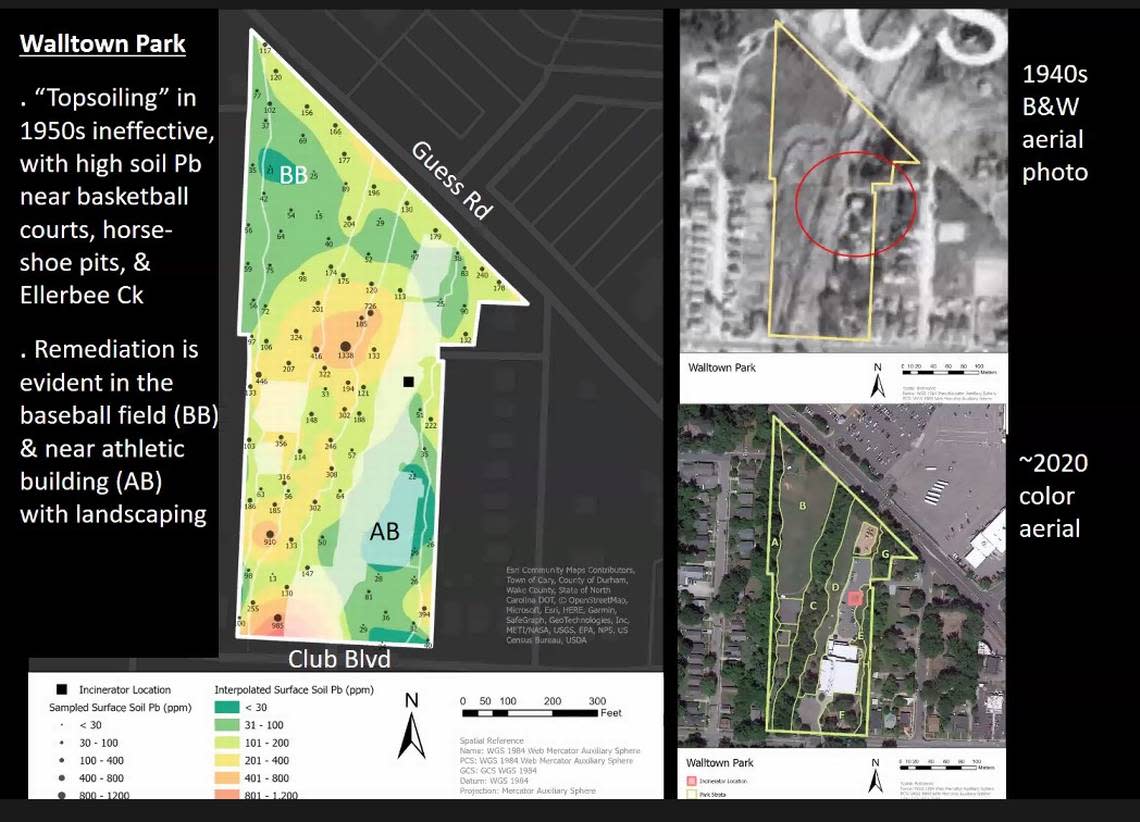

Soil scientists found high levels of lead in samples taken from parts of East Durham, East End and Walltown parks. Enikoe Bihari, a Duke graduate student, wrote a paper about the lead in Durham parks as part of a master’s degree program. It was published on Duke University’s website in December and was the first research into lead at the city’s parks.

Durham residents who are just learning about the results now have been left with many questions about how the soil could be affecting their health; and how the city and university could have known about the paper without telling them. They also want to know what steps the city is taking to make sure residents aren’t exposed to contaminated soil.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers lead in soil a hazard if it contains more than 400 parts per million of lead near children’s play areas and 1,200 ppm near areas were children don’t play. Soil in parks is a potential route of exposure, the EPA said, because young children are more likely to eat random things or put their hands in their mouths without washing them.

Scientists have linked lead with a spate of negative health effects, with children particularly at risk. Lead exposure can decrease a child’s ability to pay attention and lower IQ, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, by damaging the brain and nervous system.

“No safe blood level in children has been identified,” according to the CDC.

Solving ‘a 70-year-old problem’

In East End Park, researchers found as much as 1,364 ppm of lead in one sample. Maximum lead levels in East Durham and Walltown parks were 2,342 and 1,338 ppm, respectively.

Dan Richter, a Duke University soil scientist who advised Bihari, said, “Ash is not a good thing when it’s public waste that’s burned. Anything goes into the trash pile. Durham’s incinerator parks have been created 70 years ago.“

Referencing the contaminated soil leftover at city parks, Richter continued, “Seventy years ago. This is a 70-year-old problem.”

City Manager Wanda Page has pledged to work with a consultant to re-test the soil at all three parks, as well as at Lyon Park, which also housed an incinerator. Additionally, the city plans to host information sessions with communities near the parks and work with the Durham County Department of Public Health to explain the risks posed by lead contamination in soil.

Bihari and Richter also recommended sampling Northgate Park, which received fill from the incinerator sites in the 1950s, or the site in Northeast Durham where the city operated its combined incinerator starting in the 1950s.

Page’s note to Walltown residents this month did not mention either site.

More than 100 people attended a virtual meeting Monday evening to learn more about the report. Many called for the city to take action beyond what Page committed to in the email.

“The initial next steps that City Manager Page has indicated are a start, but they don’t go far enough,” Danielle Doughman, a Walltown resident, told The News & Observer.

Doughman would like to see a community town hall with city officials and researchers; signage in the park warning people in multiple languages of what has been found in the soil; and blood tests to measure lead levels in people who live near or frequent the parks.

“The parks are unsafe, and people need to know that,” Doughman said.

The contaminated parks

Contamination levels vary widely across each of the three parks researchers were able to test. Researchers took the soil samples between September 2021 and May 2022, with each sample consisting of the top 2.5 centimeters of soil.

At East Durham Park, the highest lead concentrations are found on the southeastern corner of the park, east of a tributary of Goose Creek that splits the park down the middle. Those include levels as high as 2,342 ppm — several times higher than the EPA’s safe level for playgrounds and nearly double the overall safe soil level.

“These are incredibly high concentrations,” Richter said.

Every sample taken in the park’s forested southeastern corner was “disturbing,” Richter added.

But researchers also took three samples on the western side of the park that tested higher than 400 ppm. One of those is near a picnic shelter.

“There are some samples there that are disturbing,” Richter said, noting that several other samples neared the EPA’s limit for playgrounds.

Durham offers free lead testing for children. Here’s how to sign up.

Contamination in East End Park is mostly found in the southwestern corner, around an abandoned City of Durham paint and sign shop. Parks and Recreation officials had to unlock the fence to the area, Richter recalled, so samples could be taken there.

In total, six of those came back higher than the level that is safe for playgrounds. The highest was 1,364 ppm.

“There’s a lot of high lead from paint just sitting on the ground there,” Richter said, noting that paint used before 1978 commonly contained high levels of lead.

Richter said an additional concern with that area is the soil can dry out and blow off the site in windy conditions, scattering the lead across nearby areas.

The researchers only tested sections of East End Park that are east of Alston Avenue, with Richter noting that additional screening could be needed at a large field and basketball courts that are west of the road.

Walltown Park presented more complicated results, Richter said. While many samples contained lead at or near the levels found naturally in the region’s soil, there were also at least six above the safe level for playgrounds with several others approaching the 400 ppm threshold.

Researchers found high samples near the park’s basketball courts and horseshoe pits.

“The park needs remediation,” Richter said.

A baseball field in the park’s northwestern corner and areas around the athletic building contained lower concentrations of lead, places Richter said could potentially serve as an example for future efforts to lower lead concentrations in soil near the surface.

Ellerbe Creek flows from south to north through Walltown Park, with a 10-foot channel depth. Bihari and Richter sampled five sites along that channel, finding layers two to eight feet thick of ash and cinder containing melted glass, metal and bricks.

Those samples contained lead ranging between 1,000 and 3,000 ppm.

Lyon Park’s footprint also historically contained an incinerator. Researchers said they couldn’t sample the park due to time constraints and believe the incinerator was in a part of a park that is now used infrequently.

Richter, the professor, emphasized that the paper in question was Bihari’s master’s project. It has not been peer reviewed and thus could be seen as carrying less weight by some scientists.

Still, Richter said, the findings were so alarming that he has helped circulate it among city officials and researchers. He and Bihari, who attended the meeting but did not speak, are now working to ensure it is peer reviewed and published.

“It’s very important to get the scientific community behind this,” Richter said.

Incinerators and contamination

Durham started burning its garbage in at least four incinerators over the course of the 1910s, Richter said Monday evening. This was not uncommon in American cities at the time.

“It was the go-to way,” Richter said.

Each one of those incinerators burned between 15 and 20 tons of garbage each day, according to a 1937 Durham Public Works map Richter showed Wednesday. He stressed that the incinerators were in a small portion of the larger park.

Then, in the early 1950s, Durham opened a larger incinerator and closed the four scattered throughout the city. Those four were turned into parks and playgrounds and, according to newspapers at the time, covered in topsoil. That is when some of the ash was moved to Northgate Park.

The construction of Walltown Park, for example, involved the removal of more than 2,000 trucks full of cinders, according to a newspaper article from the time.

Durham isn’t alone in converting former incineration sites to city parks. Richter said Similar contamination has been found in public parks in Greensboro; Jacksonville, Florida; and Atlanta.

“This Durham story is an American story, I can promise you that,” Richter said.

That story is an example of environmental racism, Brandon Williams of the Walltown Community Association said Monday evening, pointing to the decision to turn the areas near incinerators into parks and then the seeming failure to eliminate the risk posed by the contamination.

“Clearly, it seems that high risk remains in some places,” Williams said.

This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The N&O maintains full editorial control of the work.