Lawsuit accusing NC of warehousing foster kids in psych facilities survives challenge

A lawsuit accusing North Carolina officials of unnecessarily warehousing foster children in locked psychiatric facilities has survived the Department of Health and Human Services’ effort to dismiss the case.

The federal complaint contends that DHHS discriminates against hundreds of North Carolina foster kids with disabilities by warehousing them for extended periods in psychiatric residential treatments facilities.

“Often they have unnecessarily spent much of their childhood languishing in these facilities, despite yearning to be in the community,” states the complaint, filed on behalf of five youth in foster care, including children who were in the custody of Durham and Mecklenburg counties.

The lawsuit seeks class action status representing all foster youth in the facilities or those at risk of being sent to one. It asks the court to order DHHS to increase community-based placements for the children, to transition youth held in them now, and to develop policies to protect children from being sent to facilities in the future.

Additional plaintiffs include Disability Rights North Carolina and the North Carolina Conference of the NAACP. The lawsuit was filed against DHHS and its secretary Kody Kinsley.

In an order signed March 29, U.S. District Judge William Osteen denied the state’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit. He denied arguments from the state that included inadequate availability of community-based services, plaintiffs not having proper legal standing and court hearings that sent the children to the facilities.

The treatment and services that youth received was “at best, inadequate, and, at worst, highly abusive,” the judge wrote when outlining the youths’ evidence in his decision.

More than 500 children across the state were held in the facilities as of November 2021, states the lawsuit, which was filed in 2022.

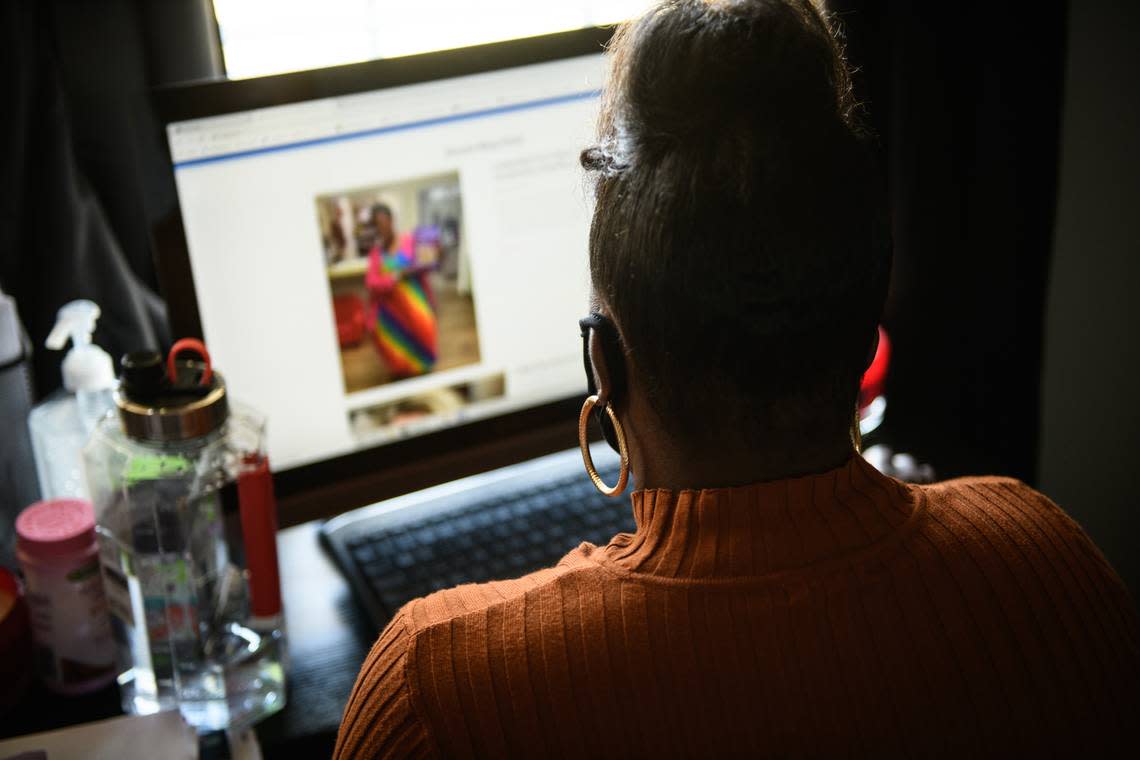

Reporting by the USA TODAY North Carolina Network in 2021, which McClatchy newspapers and other newsrooms also published, documented that North Carolina officials were sending foster children to locked psychiatric centers.

DHHS: ‘We want kids in homes’

The majority of the children placed in the facilities, which are located in North Carolina and out of state, would be better served in a community setting, and in many instances, should have never been placed in the psychiatric facilities at all, the lawsuit states.

Black children and other children of color are disproportionately represented among children in foster care in North Carolina and among those sent to psychiatric facilities, the complaint says.

In the 12-county Charlotte region, 153 Medicaid-insured children stayed at psychiatric residential treatment facilities in 2022, according to DHHS data. In the 10-county Triangle region, 89 kids stayed at those facilities.

Disability Rights has found that more than half of the children sent to these facilities were in foster care, according to Holly Stiles, an assistant legal director for the group.

The treatment is causing young people in foster care to lose important family connections and to miss out on key developmental activities, the suit argues. It says the children have also been subjected to often prison-like conditions, dangerous physical and chemical restraints and dozens of medications.

At least one of the youth, a 15-year-old from Craven County, was airlifted to a hospital trauma center after another youth slammed his head to the ground while he was institutionalized at a facility in Kinston, starting in April 2022, the lawsuit states. The teen was then taken to the emergency room with a head injury after another assault before he was discharged to a group home in January 2023.

In court papers, DHHS has noted that improving services for children with behavioral health needs in the foster care system is one of the top priorities of secretary Kinsley, who was appointed to lead the agency in January 2022.

But that requires coordinated efforts not just by DHHS but by social service departments in each of North Carolina’s 100 counties, and the General Assembly, which must pay for improvements, the department said.

“It is a long-term, herculean effort, in which DHHS plays an important, but not solitary, role,” the department wrote in a court filing.

Kelly Crosbie, who heads the department’s Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Substance Use Services, on Thursday said that the agency has been working to ensure the vast majority of foster children are cared for in communities.

Late last year, the department got $80 million from the General Assembly to invest in community-based services that are designed to keep children out of psychiatric facilities and other institutions. Among other things, the money will help provide support for foster families and will pay for therapists who can provide care to children in their homes.

“We want (psychiatric facilities) to be the setting we use the least,” Crosbie said in an interview. “...We want kids in homes.”

‘She does not feel safe’

One of the plaintiffs in the suit, a Black 16-year-old foster child who was in the custody of Mecklenburg County DSS, has been placed in dozens of different locations, including hotels, hospitals and several psychiatric facilities in the Carolinas, according to the suit.

The child — identified as “London R.” in the suit — was confined in a psychiatric residential treatment facility (PRTF) in Rock Hill, S.C. from November 2022 to at least March 2023, when the amended lawsuit was filed. It’s unclear whether she remains there today.

“This PRTF placement was not clinically-indicated,” the suit says. “It was intended only as a short-term, emergency placement. Instead, London R. has languished at this PRTF for nearly four months.”

London R. was diagnosed with PTSD, ADHD and a mood disorder, according to the complaint. Her treatment providers recommended that she be placed at a community-based therapeutic foster care program, but social service workers weren’t able to find her a program, the lawsuit says.

While at the psychiatric facility in Rock Hill, London R. was in a room with nothing but a dresser and an uncomfortable bed, and she was given at least 12 pills every day, including “a powerful cocktail of psychotropic medications” that made it difficult for her to stay awake for online schooling, according to the complaint.

Although she successfully attended a community-based school in the past, she had been given no option but to attend the online school used by the other high-school age children in the facility, the suit says.

Residents at the facility weren’t allowed to wear regular shoes outside, and were instead required to wear “shower shoes” intended to make it more difficult for them to run away, according to the complaint.

London R. has repeatedly said she wants to live in the community, the suit says.

“She does not feel safe from other residents at the PRTF, and is uncomfortable that male staff work the overnight shift on all-female halls,” the lawsuit says.

At one psychiatric facility about 45 miles southeast of Charlotte, staff implemented “a psychologically-abusive punishment resembling solitary confinement,” the lawsuit alleges. Those punished at Anderson Health Services in Marshville were confined to their bedrooms for as long as 30 days, with the exception of 15-to-30-minute walks outside, the suit says.

A child reported that a therapist at the facility “sexually touched him” during a private therapy session, according to the lawsuit. In a 2018 letter, the Mecklenburg County Department of Social Services said there was not enough information in the report to determine that abuse or neglect had occurred.

Virginia Bridges covers criminal justice in the Triangle and across North Carolina for The News & Observer. Her work is produced with financial support from the nonprofit The Just Trust. The N&O maintains full editorial control of its journalism.