10 history-making Latinos who died in 2022

Several Latinos whose lives and work left a profound imprint on American institutions — from arts and entertainment to legal and civil rights — died in 2022.

From Sesame Street's beloved "Luis" to the first Hispanic to serve in a White House Cabinet, the 10 Latinos made a mark on our nation and our culture — and expanded opportunities for those coming after them.

IRENE CARA, 63, award-winning songwriter and performer. As a child, she sang and danced on Spanish-language television in New York City and acted on Broadway. As a teenager, she appeared on PBS’ “The Electric Company” and starred in the film “Sparkle.”

But it was her recording of the title song of the popular movie “Fame” (1980) that catapulted Cara to stardom. Along with the song for the movie "Flashdance" (“Flashdance...What a Feeling,” recorded in 1983), Cara became the voice of two iconic pop anthems. The youthful exuberance of these songs indelibly defined Cara in the public eye.

“She (Cara) was one of the reasons I am here today!” tweeted John Leguizamo after her passing. “She made me believe if you were Latin you could make it!”

Born in The Bronx, Cara was of Black, Cuban and Puerto Rican heritage. She was the recipient of an Academy Award, a Golden Globe Award, and two Grammy Awards. “Irene was bubbly, ambitious and animated; she could do everything. She could sing, dance, write and act,” said music producer and composer Lee Curreri, who co-starred in “Fame.” Curreri has fond memories of bonding with Cara over their mutual passion for music. “During down times on the film, we would hang out and jam together. I loved to hear her voice, all day long. She was the real thing.”

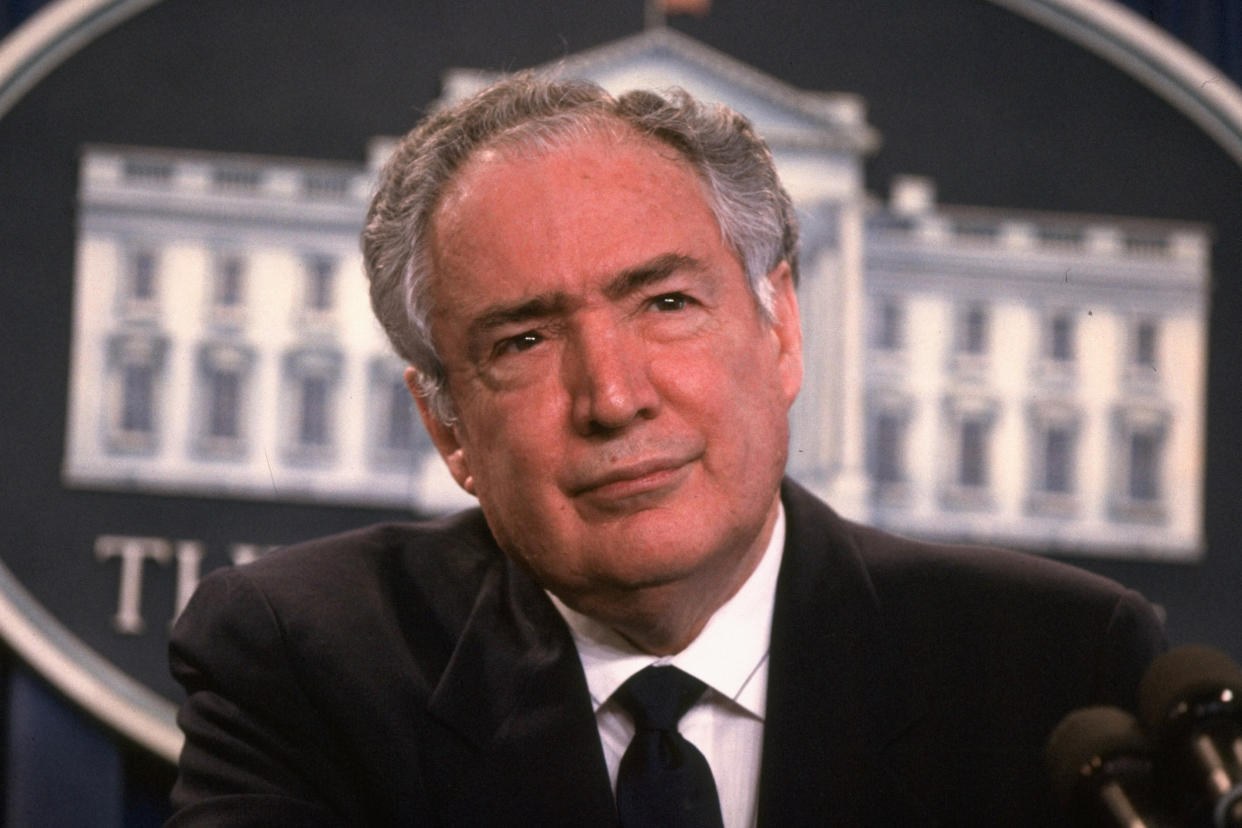

LAURO CAVAZOS JR., 95, first Latino U.S. Cabinet member. Cavazos began his education in a two-room schoolhouse on the King Ranch in Texas, where his father was a foreman. Though South Texas schools were segregated during the 1930s, Cavazos’ father fought for his son to attend a white school in nearby Kingsville. Young Cavazos became the first Mexican American student at the local elementary school — which was only the beginning of a lifetime of firsts.

Cavazos received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in zoology from what is now Texas Tech University and obtained a doctorate in physiology from Iowa State University. In 1975, he became the first Latino dean of the Tufts University School of Medicine and in 1980, he returned to Texas Tech, where he became the university's first Latino president. President Reagan named Cavazos Secretary of Education in 1988, making him the first Hispanic ever to serve in the U.S. Cabinet, a position he held under George H.W. Bush as well.

Dr. Betsy Busch, associate clinical professor of pediatrics at Tufts Medical School, praised Cavazos as “innovative and ahead of his time.”

“He was a wonderful, captivating teacher,” Busch said. “He communicated his subjects so passionately that it was infectious.” Cavazos urged his medical students to think not only about their research and patients, Busch said, but also “what they, as physicians, could contribute to society at large.”

EMILIO DELGADO, 81, actor. He was looking for acting work in Los Angeles when he got a call to try out for a new TV show aimed at children. Delgado won the part and went on to play “Luis” on “Sesame Street” for decades, earning the record for the longest-running role for a Mexican American actor on television. Delgado joined the cast in 1971, was a series regular until 2016, and participated in the show’s 50th anniversary in 2019.

At a time when positive depictions of Latinos were absent from the media, Delgado provided millions of children with a daily role model. His onscreen wedding in 1988 to “Maria,” played by Sonia Manzano, was a landmark event for public television (Elmo was their ring-bearer). Together, “Luis” and Maria” showed young audiences that Latinos were people who worked, fell in love and were part of their community.

Delgado was an activist for causes he believed in, Manzano told NBC News. When they first met, she recalled, Delgado handed out “Boycott Grapes” buttons in support of Cesar Chavez’s farm worker movement. “For us, it was important to show Latinos authentically, biculturally," said Manzano, "to portray that Latinos had the same hopes and dreams as other Americans.”

“Emilio had an amazing capacity to be nonjudgmental,” Manzano said. “He truly saw people as individuals; when he was talking to you, you were the only person in the room.”

JORGE DIAZ-JOHNSTON, 54, same-sex marriage advocate, activist. The son of a former Cuban political prisoner, Diaz-Johnston asked his then-fiancé to marry him by presenting him with his father’s ring. Yet their joy did not come easily: Jorge Diaz and Don Johnston had to fight for the freedom to legally wed, as plaintiffs in a case that is part of the history of LGBTQ+ civil rights in Florida.

Diaz and Johnston were one of six Florida couples who applied for marriage licenses on the same day in 2014. They were all denied. The couples filed suit, alleging that the state’s ban on same-sex marriage violated the Constitution. In 2015, a Florida court ruled in their favor, making Miami-Dade County the first in the state to allow same-sex marriage. That same year, a federal judge’s ruling in a separate case made marriage equality legal throughout Florida.

“My brother didn’t like discrimination in any sense; he thought that discrimination against some people was discrimination against all people,” said Manny Diaz, chair of the Florida Democratic Party. His brother was a warm, happy person, “with a strong sense of justice,” Diaz said.

“Being part of the lawsuit, that was his proudest moment,” Diaz added. “He believed in fighting to make the state better, and they made history.”

CARMEN HERRERA, 106, painter. She was born into an intellectual family in Cuba, studied art in Paris, and spent decades in New York City perfecting her painting style. Herrera used bold colors and geometric shapes in works that have been compared to Mondrian and Ellsworth Kelly. Yet she worked in obscurity for nearly her entire life, supported by her husband, a high school teacher.

Herrera’s life changed dramatically after a fellow artist recommended her for a gallery show in 2004. She sold her first painting at age 89, and was soon hailed as “the new hot thing” of the art world. Collectors and museums snapped up her work, while critics raved. The Observer of London called her “the discovery of the decade.”

“Carmen was a typical Cuban lady of her time, elegant and sophisticated,” said Tony Bechara, her friend and neighbor for over 40 years. “She was very optimistic, a glass-half-full kind of person.” Herrera used to say, Bechara recounted, that being ignored by the art world for so long was “a form of freedom,” as it allowed her to create without any expectations or judgement.

In a 2015 documentary, Herrera reflected on her late-in-life success. “There’s a saying that if you wait for the bus, the bus will come; well, I waited almost a century for the bus to come,” she laughed. “And it came!”

ROLANDO HINOJOSA-SMITH, 93, “Dean of Chicano Authors.” This proud Texan was best known for his epic series of 15 novels set in the fictional community of Klail City in the lower Rio Grande Valley. His stories examined the joys, triumphs and heartbreaks of everyday people living in the borderlands. Often compared to William Faulkner, Hinojosa-Smith was deemed “the dean of Chicano Authors” in 2014 when he received a National Book Critics Circle lifetime achievement award.

Hinojosa-Smith’s bicultural stories highlighted an area of the country often ignored or overlooked by other Americans. “He loved community, and he loved writing about his community,” said writer Richard Z. Santos. “He was a voice saying we are down here, we are living interesting lives, creating interesting art. And he was not afraid to break the conventional rules of writing.” A Hinojosa-Smith novel, for example, might include a change of narrator, a song, a poem or a transcript.

A professor of literature at the University of Texas at Austin for 35 years, Hinojosa-Smith mentored countless young writers. Jaime A. Mejia, associate professor at Texas State University, described Hinojosa-Smith as “very genial, with a great sense of humor.” Mejia noted that Hinojosa-Smith was one of the first U.S. literary voices to be published in Spanish as well as English. “He was an amazing human being. It was a joy to be with him.”

MICHAEL OLIVAS, 71, legal scholar, professor. As a young man, Olivas once studied for the priesthood, then switched to law, because he realized that “I was much better at afflicting the comfortable than I ever was at comforting the afflicted.”

Olivas spent 38 years on the faculty of the University of Houston Law Center, wrote 16 books, and was nationally renowned for his seminal scholarship on higher education and immigration law.

Thomas Saenz, president and general counsel of MALDEF (Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund) remembered Olivas as a “thoughtful, brilliant” person who helped promote legal academia as a career for Latino lawyers. For many years, Olivas publicized his “Dirty Dozen” list of top law schools with no Latino professors, which pressured schools to diversify their faculty. In 2018, the Association of American Law Schools presented Olivas with its highest honor, the Triennial Award for Lifetime Service to Legal Education and the Law.

A renaissance man, Olivas was also known as “The Rock & Roll Professor” and hosted a radio program that explored his interest in music and pop culture. New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, who gave the eulogy at Olivas’ funeral mass, described his legacy as “kindness, positivity, making a difference in the lives of others.” She added that “his heart never seemed to be too full — ever.”

TINA RAMIREZ, 92, dance pioneer and educator. The daughter of a Mexican matador, Ramirez danced on Broadway and around the world before turning to teaching. Once she realized how few opportunities there were for Latino dancers, she opened Ballet Hispánico in New York City in 1970. Her goals were to give Latinos a presence in the dance world, and to instill pride in Hispanic culture.

Ballet Hispánico began on a shoestring budget, performing in hospitals, parks and prisons. In those early days, Ramirez taught parents how to sew costumes for their children. She grew this local group of “dancers from the city’s barrios” (as The New York Times put it, in 1974) into a world-renowned arts organization. Ballet Hispánico now includes a professional dance company, a school of dance and multiple community arts programs. In 2005 Ramirez received the National Medal of the Arts, the nation’s highest cultural honor.

“Tina gave many people the right to dream, to see the possibilities within themselves,” said Eduardo Vilaro, artistic director and CEO of Ballet Hispánico. Vilaro recalled that Ramirez originally wanted to provide Latino dancers with an alternative to dancing in nightclubs and in stereotypical roles. “She created a place for people to become their best creative selves. She was a visionary.”

ERNEST Z. ROBLES, 91, philanthropist. In 1975, Robles took out a second mortgage for $30,000 to fund a new scholarship program. He and his wife wanted to make college more accessible for Latino students, and thus the Hispanic Scholarship Fund (HSF) was born. Since then, HSF has awarded over $700 million to thousands of students. The nonprofit that Robles began out of his home is now supported by major corporations from Amazon to Walmart.

“Back then, there was no model for what he was doing,” said Mike Chavez, Robles’ nephew and assistant professor of sociology at Riverside City College in Southern California. “The first HSF office was an extra bedroom in his house.” Chavez said that his uncle was most proud, not of his own accomplishments, but of the HSF recipients who went on to careers in medicine, media, law and science.

A decorated Marine Corps veteran, Robles worked as a teacher, a principal, and then for the federal government’s Office of Education. For his work with HSF, he was recognized at the White House by Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. “People said Ernest was humble and never wanted the spotlight,” said L.A. Times columnist Gustavo Arellano. “For pioneers like Robles, it was always about the work, la causa, not the limelight. But he changed lives.”

FREDDY RODRÍGUEZ, 76, artist. Born in the Dominican Republic, Rodríguez’s life changed as a young man after a teacher gave him a pass to New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. He fell in love with abstract art, and then went on to become a painter whose work touched on issues like colonialism, Roman Catholicism and Latino identity. Although his paintings have been acquired by the Smithsonian Museum and the National Gallery, Rodríguez is perhaps best known for designing the memorial for American Airlines Flight 587, a 2001 plane crash that resonated throughout the Dominican diaspora.

“What was interesting about Freddy is that his work had room to examine militarism, dictatorship — and the legacy of Dominican baseball players,” said writer and artist Marcia G. Yerman. “He refused to be pigeonholed into being one kind of artist. I think that his public art piece (the Flight 587 memorial) combined all of his talents, along with his intellect and his heart.”

Rodríguez was among a handful of contemporary painters who transformed abstraction in the 1970s, according to Alejandro Anreus, professor at Wiiliam Paterson University in New Jersey. “A lot of abstract art is about nothing,” Anreus said. “But Freddy did paintings that were densely layered, they are filled with social, political, and spiritual meaning. His body of work was about taking abstraction and filling it with content.”