‘The Last of Us’ is fiction, but these deadly fungus threats are real — and climate change could mean more of them

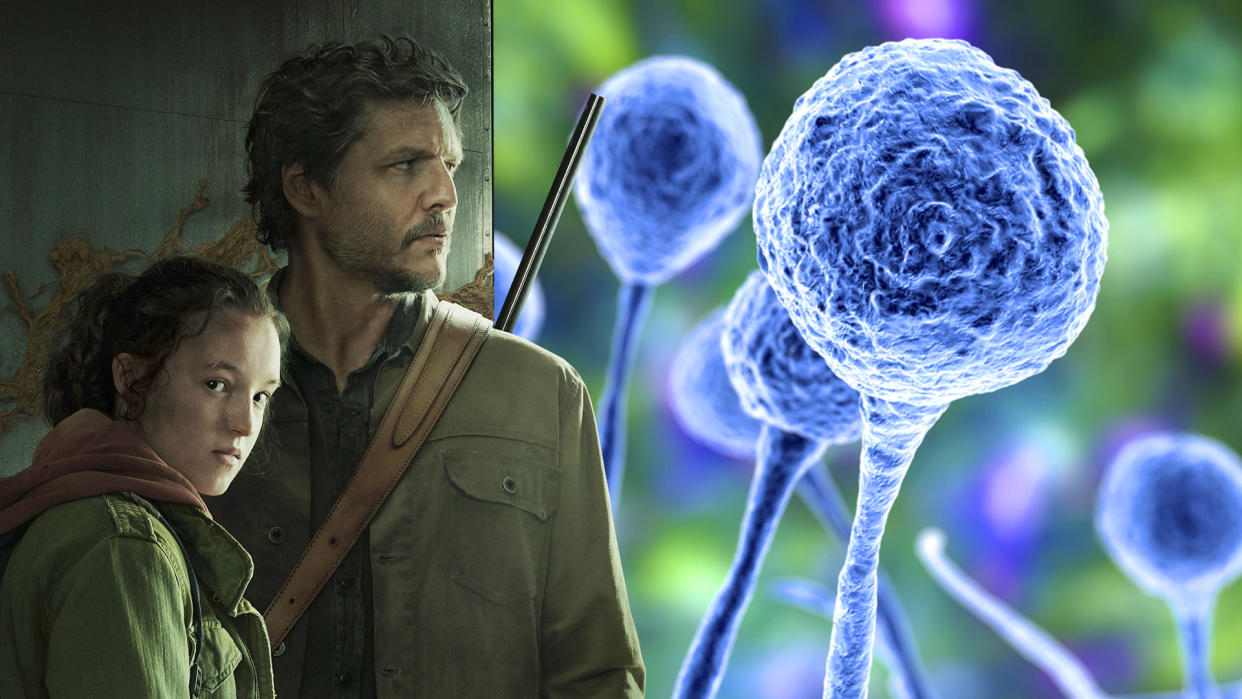

The HBO series “The Last of Us,” inspired by the video game of the same name, has captured many people’s imaginations, by proposing the possibility of an extinction-level threat from a seemingly innocuous organism: fungus.

The popularity of the show has provided a massive PR boost for fungi — an area of science that experts argue has been ignored and underfunded for decades. But while a fungus zombie apocalypse or COVID-19-like pandemic is extremely unlikely, many in the infectious disease community do believe fungi will pose a greater threat in the future as new fungi adapt to infect humans.

Dr. Andrej Spec, who specializes in fungal infections as associate director of the infectious disease clinical research unit at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, told Yahoo News that fungi are chronically misunderstood, although they pose a major health threat. Many people associate fungi with toenail infections or benign skin rashes; meanwhile, fungi are responsible for about 1.7 million deaths each year, and some species have incredibly high mortality rates.

“I think it's unlikely we're going to have a billion-person death event from fungus. But it's quite likely that we'll have an emergence of a new fungus that may, in the next 20 years, be responsible for a couple 100,000 deaths a year,” Spec said.

“And you know, we already have many fungi that cause a couple 100,000 deaths a year — we just ignore them, because we have this narrative that fungi are rare,” he added.

The truth behind that fungus in 'The Last of Us'

Cordyceps is a real fungus that’s featured in “The Last of Us.” On the show, a species of cordyceps gets into the food supply, manipulates the brains and bodies of anyone who eats it and turns them into zombielike creatures intent on spreading the fungus to every living person.

In reality, cordyceps can be safely ingested by humans; it’s been used in Chinese medicine for years, and it has been claimed that it can give your immune system a boost.

The real threat posed by cordyceps is to arthropods, like insects or spiders. As “The Last of Us” suggests, the fungus does indeed drug its victim’s brain, compelling it to migrate to a humid environment that helps it to spread, eventually killing its host and growing out of its body to spread more spores and ensnare more prey.

But fortunately, our brains are very different from the brains of an ant.

“We're very different from arthropods. We're evolutionarily almost, I think, a billion years separated at this point,” Spec said. “So in that sense, cordyceps is not dangerous. It has never to the best of my knowledge ever infected any vertebrates, and so it's unlikely that it would ever cross to us.”

The real fungal outbreaks: From drug-resistant threats to one that 'literally eats your face'

While cordyceps are harmless to humans, hundreds of other fungi are indeed toxic — and some deadly. Last year, in response to the increased threat of invasive fungal disease the World Health Organization released its first ever list of fungal priority pathogens.

Unlike bacteria and parasites, Spec said, scientists only discovered fungi relatively recently; so understanding their role in history is tricky.

One decades-old and controversial theory, for example, attributes the 17th-century Salem witch trials to hallucinations caused by the fungus known as ergot — although Jason P. Coy, history department chair at the College of Charleston and author of “The Devil’s Art: Divination and Discipline in Early Modern Germany,” said that has been largely debunked by historians.

“This 1976 theory proposed a medical explanation: convulsive ergotism, which is caused by ingesting a fungus that grows on wet grain. It produces hallucinations like LSD,” Coy said in an email to Yahoo News, “but doesn’t help explain the Salem afflictions, because the accounts from 1692 don’t mention many of the symptoms associated with convulsive ergotism, like vomiting, diarrhea, or gangrene of the limbs (and eventually, with prolonged exposure, even death).”

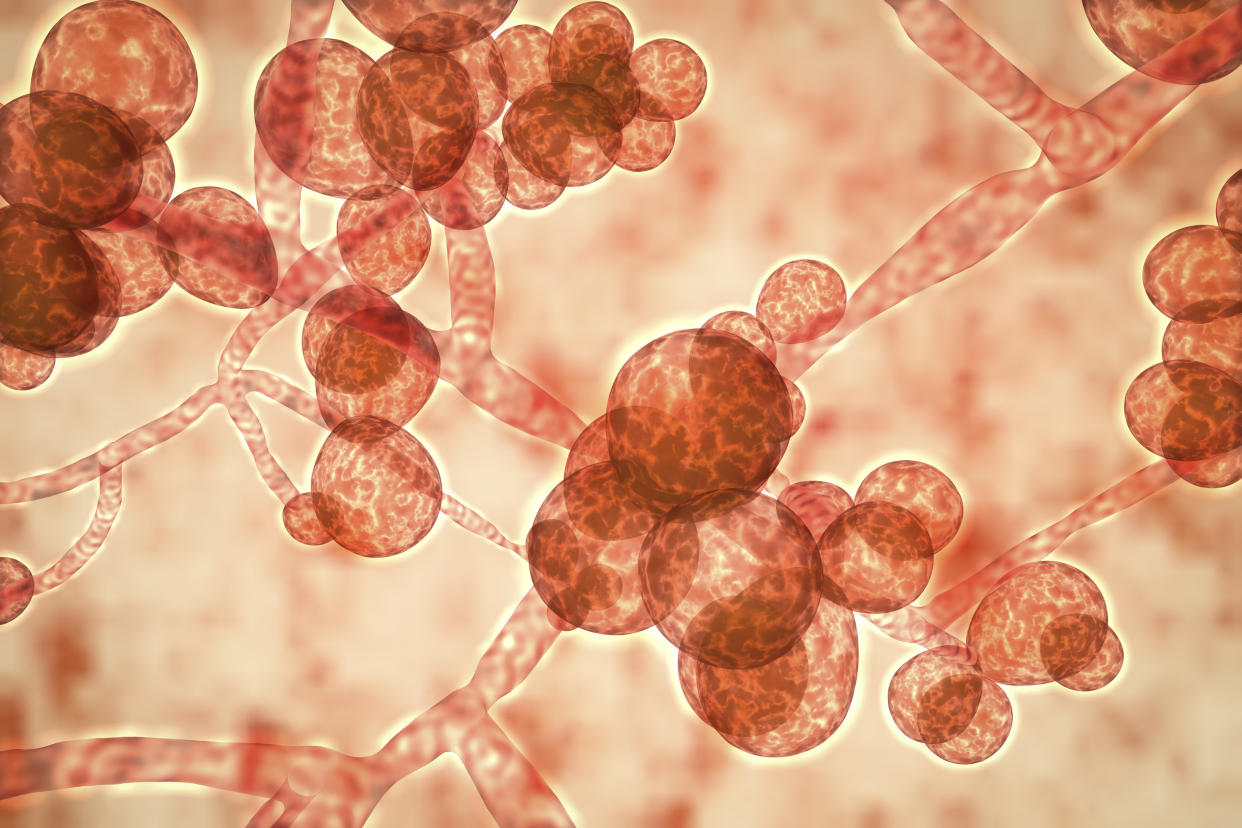

But other fungal outbreaks are verifiable, much more recent — and perhaps even more gruesome than anything Hollywood could concoct. In 2021, as the COVID-19 Delta variant swept through India, so too did a wave of “black fungus” known as mucormycosis. Like most fungi, it doesn’t spread through person-to-person contact. However, reduced immunity caused by misuse of steroid treatments during the COVID pandemic, the wet weather season and higher instances of diabetes in the population created the perfect confluence of circumstances for mucor to take hold, with tens of thousands of people infected in one year.

“It's barbaric, and honestly, I am not exaggerating when I say it literally eats your face,” Spec said of the fungus. “It’ll eat the face, eat the eyes, and eventually end up in the front part of their brain and liquefy the brain and eat it.”

The treatment, Spec said, involves aggressive, often disfiguring surgery, combined with aggressive antifungals.

Another fungus that currently poses a threat, called Candida auris, was first discovered in humans in 2009. Since then, Spec says hundreds of thousands of cases have been identified in countries around the world, including in the United States. Researchers believe the fungus, which is highly drug-resistant and fatal in one-third of patients, was able to adapt to infect humans thanks to rising temperatures due to global warming.

And it’s not the only fungus that may be adapting to survive in human hosts.

“We also have emergence of random fungi that have never really caused human disease before,” Spec said of his clinic. “We get these cases two, three or four times a year, where it's a fungus that has never before been described to cause human disease before, so it's a whole new fungus.”

Climate change and losing 'one of our biggest protections against fungi'

In the first episode of “The Last of Us,” there’s a scene where an epidemiologist from the 1960s sits calmly on the stage of a television program, cigarette in hand, and coolly describes how fungi could evolve to infect humans.

“Fungi cannot survive if its host’s internal temperature is over 94°F, and currently, there are no reasons for fungi to evolve to withstand higher temperatures,” he says. “But what if that were to change? What if, for instance, the world were to get slightly warmer? Well, now there is reason to evolve.”

“That opening scene from ‘The Last of Us,’ there's many of us who were like, ‘We could have given that exact same speech.’”Dr. Andrej Spec, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Spec said that scene struck a chord; while something akin to a zombie apocalypse is extremely unlikely, he said the increasing crop of emerging fungal infections probably has something to do with the rise in average temperatures.

“It's kind of like that opening scene from ‘The Last of Us.’ There's many of us who were like, ‘We could have given that exact same speech,’” Spec said. “Much of it is largely true; as we warm up, we lose one of our biggest protections against fungi: our body temperature.”

Fungi, Spec explained, don't do well at 37°C — or 98.6°F, which is the average body temperature of humans — and thrive best at temperatures around 25°C (or 77°F). But more and more instances of extreme heat are weeding out those fungi that can only survive more temperate temperatures, and enabling more heat-resistant fungi to thrive.

“Every time we have these genetic bottleneck events — like two years ago, where France reached 45°C [113°F] for like four days — that causes massive die-offs in the fungal microbiome in the soil. And we are selecting for isolates that are more temperature-resistant,” Spec said.

A recent study from Duke University found that an increase in temperature caused fungus to turn its adaptive responses “into overdrive,” prompting it to mutate and evolve at higher rates — which may enable it to acquire higher heat resistance and perhaps “greater disease-causing potential.”

“The biggest, scariest thing is that some of these molds actually may have all the things in terms of their environment, in terms of their molecular machinery, to infect a human and kill a human — and to be drug resistant to all of our therapies,” Spec said. “All that they're missing, kind of the missing link, is that they're not temperature-tolerant.”

Warmer temperatures also mean that certain disease-causing fungi can now thrive in areas that were once uninhabitable. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that Valley Fever, for example — a disease caused by the fungus Coccidioides, which is usually found in areas with dry, hot soil — has spread to the Pacific Northwest.

“As the difference between environmental temperatures and human body temperatures narrows, new fungal diseases may emerge as fungi become more adapted to surviving in humans,” the CDC says, also noting that more flooding and natural disasters due to climate change may increase the risk of mold growth in general, which could lead to more fungal infections.

Fungi spread through spores that are all around us, in the air we breathe, all the time — and usually our immune systems can handle them. Those with compromised immune systems tend to be much more susceptible to fungal infections than immunocompetent people, although Spec does point out that around 15% to 20% of patients he sees with infections are otherwise healthy and immunocompetent.

“The concern that a lot of us have is that it's a tipping scale,” Spec said. “If you have an organism that can just barely infect some of us — like one of the things that it doesn't like about us is temperature, and so it has to deal with the temperature. Well, what if it gets so much better at dealing with the temperature of our bodies that now it doesn't need that weakened immune system in order for us to be more prone?”

Could we have a fungus pandemic?

One study estimates that over 150 million “severe cases of fungal infections” with about 1.7 million fungus-related deaths occur worldwide each year. But while emerging fungi do pose a possible threat, Spec said it’s unlikely we would see a fungal pandemic at the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic, where a single virus has been responsible for over 6.8 million deaths worldwide since emerging three years ago.

“The fact is, it hasn't happened ever, so it's very unlikely to actually happen,” Spec said. “But if it did, we don't have a game plan, because we've also systematically underfunded research and fungus for a century.”

There are currently zero antifungal vaccines, though many antibiotics and some cancer drugs are derived from fungi. Spec said we are still discovering all the things that fungi are uniquely capable of, from “eating” radiation to increasing and lowering its own number of chromosomes — something, Spec said, that no other organism is capable of.

“I respect fungus more than viruses,” Spec said. “Viruses are so much less capable in terms of what they do. Fungi are just these brilliant architects of biochemistry, and they can do some of the most amazing things. And we have barely begun to scratch [the surface of] what they do.”