What was it like the last time Miami hosted political conventions? It wasn’t quiet

Miami wants to host the Republican National Convention in 2028.

If the Magic City wins the bid, it would be the first time the region has hosted a political convention since 1972, when Miami Beach hosted both the Democrats and Republicans. Miami Beach also hosted the GOP convention in 1968.

Miami’s bid is offering the Miami Heat bayfront arena for the the event where Republican leaders will select a nominee for the 2028 presidential election. In the past, the gatherings were at the Miami Beach Convention Center.

So, what was it like the last times South Florida hosted political conventions?

The Vietnam War took center stage, and there were protests and social unrest.

Here’s a look back from the Miami Herald archives:

Flamingo Park encampment

Published March 11, 2019

By Kyra Gurney

In the early 1970s, Miami Beach was a sleepy city known more as a haven for vacationers and retirees than anything else. Hotels seen as trendy today were largely occupied by seniors who passed part of their days lounging in front on beach chairs.

“It was quiet, there was not much going on. It certainly wasn’t like today,” recalled former Miami Beach Commissioner Nancy Liebman, who first moved to the island in 1969. “All of the sudden when this convention came there was so much going on — protests and Richard Nixon and all that he was involved in.”

The 1972 Republican convention attracted all types of political activists and counterculture groups: There were hippies, Marxists, gay rights activists, Vietnam veterans and members of the Black Panther Party, just to name a few. They all camped in Flamingo Park, which was walking distance from the Miami Beach convention center where the main events were held. The area soon filled with clouds of marijuana smoke. The Miami Beach police chief allowed the protesters to sleep in the park, which had more open space in those days, because he feared that otherwise they’d pitch their tents on residents’ front lawns.

Police and government officials worked hard to keep the protest groups apart, designating separate demonstration routes to avoid clashes, former Miami Beach Mayor Seymour Gelber recalled in his privately published memoir.

“One of my assignments was to stroll through the park each morning checking out problems in the making. In the process I became expert at distinguishing the different brands of pot each group used,” wrote Gelber, who was a prosecutor at the time and wouldn’t become mayor until 1991.

But while officials took care to keep the groups apart, to many residents and convention delegates they were all — as one attendee told the Miami Herald at the time — “the great unwashed masses.”

Pomerance, pomp and the protests

Published July, 2002

Warren Beatty came to town. So did Julie Christie, Shirley MacLaine, Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, and the Democratic Party’s heaviest hitters: George Wallace, Edmund Muskie, Hubert Humphrey, Ted Kennedy and a South Dakota senator named George McGovern.

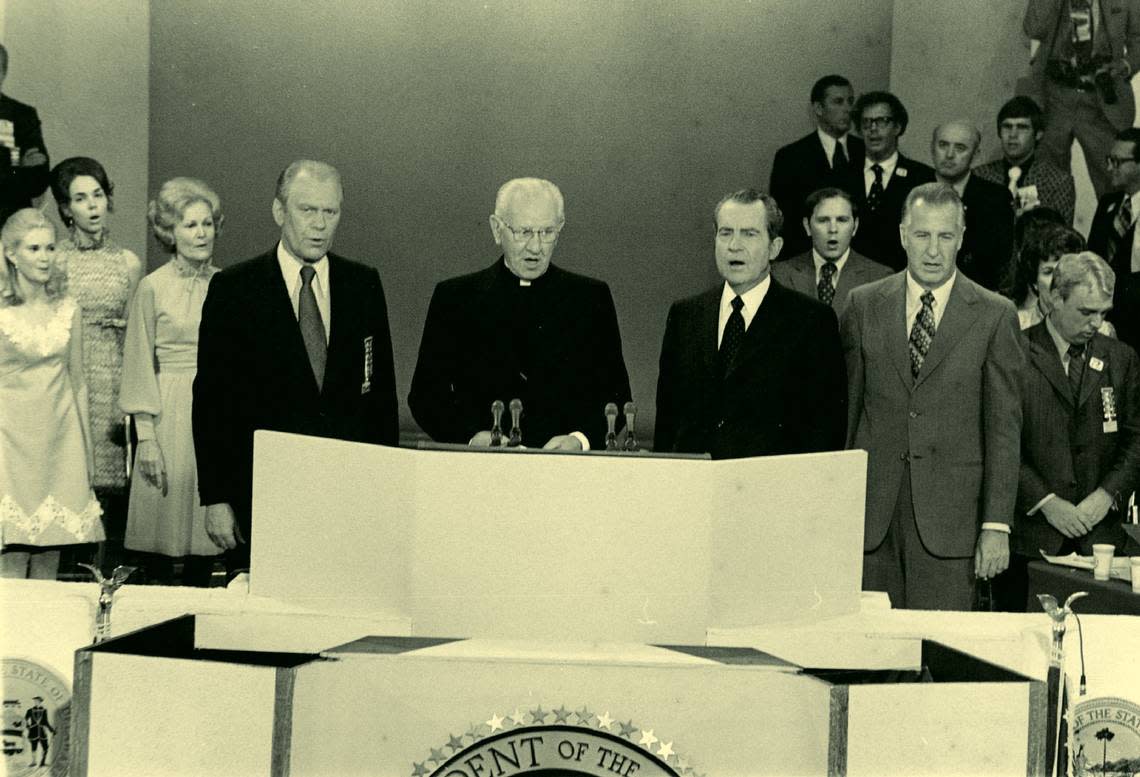

When it was the Republicans’ turn six weeks later, Jane Fonda arrived fresh from a two-week tour of North Vietnam - to help galvanize the anti-war protests. The other entertainers who showed up - Sammy Davis Jr., Frank Sinatra and Jimmy Stewart - came to support the president. That would be Richard Nixon. He was running for reelection, along with his vice president, Spiro Agnew.

In 1972, first the Democrats, then the Republicans held their national convention in Miami Beach. With memories fresh of the riots at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, local police were given riot helmets, three-foot-long billy clubs, chest-high plastic shields and masks for tear gas.

But the riots materialized only briefly, in large part because of the tactics of Miami Beach’s gregarious police chief, Rocky Pomerance.

The 275-pound Pomerance was a former mailman whose face, according to a Herald profile written then, “still bears traces of the boxing ring.” He liked to quote Shakespeare and Tennyson, and he didn’t adhere to the typical police approach of the times to street disturbances: cracking the heads of everyone in sight, as Chicago police had done. Pomerance emphasized nonviolence, negotiation and turning a blind eye to minor infractions such as smoking marijuana in public.

With the nation’s eyes upon South Florida twice in one year - first in July for the Democratic gathering, then in August for the Republican event - Pomerance’s approach worked, except for the final night when the anger and the passions of the turbulent time couldn’t be stilled.

In 1972, both conventions were at the Miami Beach Convention Center. It was a different time, a different era.

The Vietnam War still raged, and so did protesters in the streets. They promised to come to Miami Beach in full force. Local authorities were on edge even before the Democrats were gaveled to order on July 10.

One rumor had anti-war protesters planning to cause havoc by dumping LSD into the local water supply. They were also said to be planning to scatter marijuana seeds from the air so pot plants would be plentiful.

Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, who led the Youth International Party - the Yippies - told Pomerance at a public meeting that they planned to lead 10,000 naked protesters down Collins Avenue.

“If you can get 10,000 people to walk naked down the asphalt on a hot July day, I’ll lead the parade,” Pomerance responded. “And wait until you see what I use for a baton.” Everyone laughed but Rubin and Hoffman.

Yippies, Zippies, Vietnam Veterans Against the War, the People’s Pot Party, the Young Socialist Alliance, Students for a Democratic Society - all came to Miami Beach to attract attention for their causes.

On Pomerance’s recommendation, Miami Beach City Commissioners made Flamingo Park available to what were called the “nondelegates.” Uniformed police would stay out.

Several thousand youths set up tents and lean-tos in the park five blocks south of the convention center. They were free to smoke marijuana, or do just about anything else that was peaceful.

Murray Dubbin, a dapper Democratic state representative, smoked a pipe as he walked in the park one day.

“Hey, man, what have you got in that pipe?” a protester called out. “I’m smoking the usual,” said Dubbin.

“Your usual or our usual?”

That kind of stuff appalled law-and-order types such as Harold Rosen, a World War II and Korean War veteran who was Miami Beach’s vice mayor. Just before the convention began, a Yippie tried to toss a 39-cent pumpkin pie into his face at a City Commission meeting. Rosen decked him with a right to the jaw.

“I didn’t want them sleeping in Flamingo Park,” Rosen said recently.

But Pomerance figured that he could control protesters more easily if they congregated in one place. He also made it a point to befriend Rubin, Hoffman and other leaders. He even provided them with bullhorns.

Pomerance understood that they wanted the attention of television cameras and newspaper reporters, not a nightstick to the head. So with the help of Seymour Gelber, who worked for the state attorney’s office, Pomerance negotiated the details of each day’s protests in advance.

But to acquire more information, he sent undercover cops to the park.

“We’d float into Flamingo Park and go from tent to tent,” said Richard Barreto, then a 23-year-old cop who later became Miami Beach’s police chief. He wore a tie-dyed shirt and bell-bottom jeans with flowers and peace signs sewn in them. He had a headband around his afro. Neighbors thought he was a drug dealer.

Flamingo Park “was a Woodstock-like atmosphere,” Barreto added. “They would organize with their bullhorns. We’d provide information to our superiors so they’d have a heads up.”

Later in the convention, when he wore a uniform, Barreto picked flowers on Lincoln Road and gave them to demonstrators. “It would take the wind out of their sails.”

During the four-day Democratic Convention, only two people were arrested and two others injured. Four years earlier in Chicago, 680 people were arrested and 1,381 were injured. “A Triumph of Maturity,” The New York Times headlined. Pomerance received kudos from Walter Cronkite on down.

The action inside the convention hall was peaceful, although unruly.

Senator McGovern, a preacher’s son who promised to end the war, arrived in Miami Beach just short of the delegate vote count needed to win the nomination. Sen. Humphrey, Gov. Wallace and Sen. Muskie each held out hope that he could deny McGovern a first-ballot victory and win the nomination himself. But with his 34-year-old campaign manager, Gary Hart, managing the action, McGovern won a floor fight the first day to claim the necessary delegates.

He picked a little-known senator from Missouri, Thomas Eagleton, as his running mate. But the schedule spun out of control on the final night of the convention, when McGovern was to accept the nomination before a nationwide television audience. Delegates insisted on voting for 80 people for vice president - sitcom character Archie Bunker among them - so McGovern spoke long after most Americans had gone to bed.

“It was the best 2 a.m. speech you never heard,” said Mike Abrams, then a young party activist and later a state representative.

In winning the nomination backed by peaceniks, women activists and black supporters - typically labeled “insurgents” by the press - McGovern smashed the aging coalition that had carried the Democratic Party since the New Deal. In the process, he alienated Big Labor’s boss, George Meany, and such big-city bosses as Chicago’s Richard Daley.

McGovern never had the chance to unify the party. Before the month was out, Eagleton had stepped aside following disclosures that he had undergone electric shock treatments in the 1960s. Sargent Shriver, a Kennedy-brother-in-law, replaced him.

By the time the Republicans met in Miami Beach beginning on Aug. 21, Nixon held an insurmountable 26-point lead over McGovern. His aides carefully scripted the convention, minute-by-minute, even allowing time for “spontaneous” laughter.

Once again, Pomerance and city officials opened up Flamingo Park to demonstrators, “though protest groups figure to make more trouble this time,” Newsweek reported.

The protesters’ numbers had nearly doubled, and they were angrier, given that it was Nixon’s war.

On the night before the Republican Convention began, protesters surrounded Mike Thompson’s new Lincoln Continental as he drove five other orange-jacketed Florida delegates by the Fontainebleau Hotel. The demonstrators pounded on the car. “We were scared for our lives,” he recalled. He stepped on the accelerator. They fell by the wayside.

The following night, hundreds of Vietnam veterans marched on the convention center in the rain, chanting, “Bring our brothers home.”

A night later, when delegates formally nominated Nixon, the protesters turned the heat up a notch, shattering windows and denting cars outside the convention hall. For the first time, Pomerance ordered widespread arrests. In all, 212 men and women were detained.

Authorities learned that the antiwar demonstrators planned to disrupt the convention the following night, Aug. 23, when Nixon would end the gathering with a prime-time acceptance speech. The officials brought in 50 buses to seal off an area fronting Meridian Avenue where protesters planned a sit-in blockade. They also decided to bus in all delegates from their beach hotels.

That night, one group of protesters marched on the Fontainebleau, a prime locale for delegates. Another group headed to the convention center. Many of these protesters were looking for trouble.

They succeeded in forcing delegates off several buses. “Twenty hippie girls surrounded me,” one young female South Carolina delegate told The Herald. “They bounced me around like a ping-pong ball.”

The Republican delegates felt terrorized. But all of them made it into the hall, and the convention went off as planned. Police did arrest 934 people, but only 33 people were injured.

Chicago is remembered for its violence. Miami Beach is not.

“Afterward, we felt like we had done our job,” said Gelber. “They had been entitled to protest, and they had protested. There were no major injuries, and we got them out of Miami Beach safely.”

Pomerance - who died in 1994 - won such acclaim that he was hired to help plan future conventions, and his methods became standard operating procedure. “Rocky was a dominating figure,” Gelber said.

The scene

Published April 22, 1984

Ah, what might have been. Ten thousand naked protesters led by a 250-pound police chief wearing nothing but size 12 flip- flops, marching down Collins Avenue on Miami Beach while the world, as they say, looked on.

Cruel words: what might have been. It would have been a memorable sight.

“I told war protest leader Jerry Rubin that if he could get 10,000 people to walk naked down Collins Avenue, I’d lead it,” said the redoubtable Rocky Pomerance, Miami Beach’s most famous police chief, smiling at the recollection and, perhaps, at its photogenic possibilities. “Everybody started laughing except Rubin and Abbie Hoffman. And I suddenly realized they were not the real leaders any more.”

The walk of the naked living didn’t take place during the political conventions of 1972. But just about everything else did.

It was the summer of our discontent. Vietnam churned the national soul. In its gory wake, respect for authority had sunk from sight. Four years before in Chicago, protesters, police and Mayor Richard Daley had turned the Democratic Convention to carnage.

And now the Jerry Rubins and Abbie Hoffmans of the world had proclaimed Miami Beach and its two summer political conventions the “beginning of the revolution.”

“Those were pretty heavy days,” says Richard Reeves, syndicated political columnist and author. “Rocky was the police after Richard Daley. To understand what he accomplished>, you’ve got to understand what that means.”

The Democrats still understand. Which is why the party has hired Pomerance and his consulting partner, Jim McDonnell, as security advisers for the San Francisco convention, which begins July 16. For Pomerance, this will be the seventh national political convention he’s worked.

The two have co-consulted for the Democrats and Republicans in 1976 and for the Democrats again in 1980.

Pomerance, who is on the board of a security alarm system company, will advise on outside security: marches, protests, police actions, strategy. McDonnell, president of a security guard company, will advise on inside security: internal flow of delegates and press, credentials, safety.

It’s a long way from Miami and the heat of 1968 and 1972. But the mission, Pomerance says, will be the same: make certain local residents’ rights are protected, make certain delegates can pursue their business safely and make sure the rights of legitimate dissent are protected.

“This effort they’re making in San Francisco to deal with the gay groups that want to protest at the convention> to avoid confrontation, Rocky was the first one to do that. It saved a lot of trouble. And a few heads,” Reeves said.

Praise of Rocky Pomerance is easy to come by.

“His advice, his knowledge, its depth and breadth have been invaluable to us,” says the man in charge of convention security, Kevin J. Mullen, San Francisco’s deputy chief of police for staff services. “He literally wrote the book on convention security. He’s a very special guy.”

“He’s shrewd. He has this wide peripheral vision. He could shift gears. And he would anticipate responses,” says Dade Circuit Judge Seymour Gelber, who in 1972 was the assistant state attorney attached to Pomerance’s office to help with convention details.

“We met with Jerry Rubin one day and Rubin was literally flustered. He thought he’d be dealing with this hard, tough cop, and Rocky started talking to him like a social worker trying to save the world. Rocky took the play away from him.”

In a time of “tremendous pressure,” Gelber says, Pomerance began to experiment. His theory: Communicate with protesters, police and the public. Make them understand the game rules. Tell them what would happen if the rules were broken. And do it in a way that convinces but doesn’t threaten.

“He started this whole process of educating police officers so they could react to Yippies without violence,” Gelber says. “And he met with the kids every day. He made them feel they were part of the system and constrained by it, rather than it being an excuse for them acting out.”

Pomerance received a great deal of publicity from his stint as convention commandant. It glowed.

Reeves called him “the thinking man’s cop.” He starred not only in the local media but in The New York Times, The Washington Post, national news magazines, radio, television and even the Doonesbury cartoon strip.

“He earned all of it, and probably more than he got,” Gelber says.

Pomerance’s wife, Hope, was impressed.

“That’s wonderful, El Jefe Chief,” Pomerance says Hope told him. “Now how about taking out the garbage.”

On one level, all the attention pleased the ebullient, gregarious Pomerance, who is, Hope says, “the best public relations man I ever met.”

On another level, however, he still is mildly embarrassed that he reaped the public attention for work done by scores of people during the conventions.

“I had enormous support during 1968 and 1972,” Pomerance says.”

Former Dade County Manager Ray Goode is a perfect example. He coordinated all the other parts of this. I wasn’t looking for more, I was looking for less. I didn’t want to be the boss over anything else. I just wanted the convention to work.”

To make it work, Pomerance’s skill as public relations man, diplomat and social psychologist became as important as his skill as policeman. The Democratic and Republican conventions of 1972 were a victory of style as much as substance, Reeves says.

“On the other hand, I think style is substance,” Reeves says. “And I believe public relations is about 80 percent of a policeman’s job.”

“Rocky tiptoed through all the problems, danced at all the weddings,” Gelber says. “And he did it with a diplomacy that would put Henry Kissinger to shame.”

Yet substance was there when he needed it.

“People forget that in 1968, the Chicago police made 350 arrests. In the 1972 Republican convention, we made 1,400 arrests,” Pomerance says. “Many had a commitment to be arrested. I decided I would honor that commitment. What I had to decide was what level of action would allow the demonstrators to save face, but still ensure that the next day the city would still be there.”

How he came by these diplomatic skills is as much a mystery to Pomerance as it is to those who know him. He was born poor and Jewish in the Bronx in 1927. His given name is Arnold, not Rocky, something he changed legally during a six-year sortie into Beach elective politics in the 1950s.

He fought on the street and boxed as an amateur during tours with the Merchant Marines and the Army. He began his public service career not as a cop, but as a postman on Miami Beach. He applied to the police force not through a passion to serve society, he says, but because it paid more.

He stayed a policeman for a reason that won’t show up on his resume. As a 17-year-old seaman, he took an unauthorized (albeit accidental, he contends) stay in Panama and learned Spanish from a uniquely patient daughter of delight.

In Miami Beach in the early 1950s, he was the only beat cop who could talk to the growing number of South American tourists. His chief hired him full time, he says.

“Whenever my kids he has three would get a little angry, I would tell them no matter what the adversity is, profit by an experience. If I hadn’t been with a Panamanian...er, lady, as a 17-year-old, I wouldn’t be the police chief today.”

Brilliance has played a smaller role in his career, Pomerance believes, than serendipity has.

He was appointed chief in 1963. In 1965, he arrested and charged his first boss, then-city manager O.M. Pushkin, in a drinking and driving scandal. Oddly, that incident imbued his career with a special quality.

“All the old timers in the city said, ‘Jesus, stay away from that guy Pomerance. He arrested his boss, he’d probably arrest his mother.’ Politicians obviously decided I was no one to, quote, deal with or confide in. I felt very badly for the city manager, but at the same time the incident set a tone for my career.”

1968: A watershed year when the GOP gathered in Miami Beach

Published Aug. 2, 1998

By Martin Merzer

It was 1968. We lost our heroes and a large measure of innocence. We learned a lot, but at a ghastly price.

It was a watershed year of turmoil and grief, Hair and Hey Jude . A year that profoundly refashioned the nation and the world. A year that still resonates 30 years later.

“I call it the reconstruction period of America because of all the changes,” said Bob Beamon, 52, of Aventura, who won a gold medal in the 1968 Olympics. “Whatever we were protesting, we learned that patience is important. Nothing comes easy.”

Nothing comes easy. That’s one thing the nation learned in 1968.

Assassinations abbreviated dreams. Riots convulsed cities. Students wore flowers in their hair and seized campuses. Tanks rumbled through Asian jungles, European capitals and American streets. In Vietnam, 14,589 Americans died, the highest annual toll of the war. In Washington, a president spurned reelection.

Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?

And, in 1968, Republicans assembled in Miami Beach to nominate Richard Nixon. “The long, dark night for America is about to end,” he said.

Six miles away, during a night long and dark, Liberty City flared with the fires of racial discord.

“It was a much more complex year than a lot of people think,” said Greg Bush, now a history professor at the University of Miami, then a young protester at Colgate University. “It wasn’t just Vietnam and civil rights. It was more than that -- real anger at long-term, fossilized establishments.”

This passion played itself out during 1968, he and others say, and then it was over.

By the end of the year, flower power wilted and a veil of cynicism descended. Many learned, or thought they learned, that government could not be trusted, and that it took more than dreams and demonstrations to change the world.

They turned inward, ultimately trading love beads for corner offices, petition campaigns for minivans, marijuana for Valium and bran flakes.

Many others yearned for stability. The noise and tumult of 1968 forged the backlash of the Silent Majority, historians say, and then the conservative coalition that propelled Ronald Reagan into the White House and fueled the Republican revolution that still controls Congress.

“There had been no other year in our history with such multiple seismic tremors as ‘68 was to bring. . .,” novelist John Hersey wrote. “No single one of its shocks was to turn the country around, but the shocks were to keep coming and coming.”

Domestic shocks: Assassins killed Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy. More than 130 U.S. cities self-immolated in paroxysms of fury. Ten thousand “flower people” staged violent protests during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Foreign shocks: North Korea seized the USS Pueblo and its 83-man crew. North Vietnam and the Viet Cong launched the Tet Offensive. Soviet troops and tanks suppressed stirrings of freedom in Czechoslovakia. Antiwar protesters and new-fangled anarchists rioted in France, Japan, Mexico, England and elsewhere. American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised clenched fists of black power at the Olympics.

South Florida shocks: Nixon came to Miami Beach with the nomination virtually sewed up, but with a surprise up his sleeve. He chose as his running mate Spiro Agnew, the little-known governor of Maryland and a strong foe of what was then called “Negro militancy.”

While the convention was under way, Liberty City erupted when a “Vote Power” rally cartwheeled out of control. Three died and more than 50 were injured in two days of looting and violence that put the entire region on alert at a delicate time, public relations-wise.

“This has not been a riot,” Dade Sheriff E. Wilson Purdy kept telling the national media.

But the year also brought this: Congress passed civil rights legislation intended to end discrimination in housing, and Vietnam peace talks began, and 62 nations signed a nuclear nonproliferation treaty.

And Hair let the sun shine in on Broadway and 2001: A Space Odyssey floated across movie screens and Aretha Franklin recorded Think .

Think. Think about what you’re trying to do to me.

Think about how different race relations and politics and history might be today if King and Kennedy had survived.

Would King’s nonviolent movement have re-energized itself by forging a link with poor whites? Would Kennedy have been elected president with a mandate to end the war and attack poverty and reunite the nation?

Think about how different our cities might be if we had not so vividly experienced the human and economic toll of war.

In 1968, 536,000 American men and women were in Vietnam and the war was costing $30 billion a year. At home, crime began to explode, inflation to bubble. An economic harbinger: Hershey reduced the size of its 10-cent chocolate bar from 1-3/4 ounces to 1-1/2 ounces.

Think about how different our social atmosphere might be today if the young of that time had not developed their sometimes disdainful disposition toward authority, their casual style of dress and address, their liberated -- some would say licentious -- attitude toward drugs and sex.

If they had not developed an increasingly keen awareness of society’s inequities toward women, blacks and Hispanics, and a determination to right these things that were wrong.

Beamon: “We all wanted the same thing -- to be treated as human beings.”

In 1968, Jan Herard was a stay-at-home mom. Five years later, she rejoined the work force. Now 53, she is a real estate broker in Plantation.

“Everything changed and the opportunities were there, but the responsibilities increased and the pressures on the family became much greater,” Herard said. “That’s when you saw the ‘I can have it all, so why don’t I get it all?’

“Something got sacrificed along the way, and I do believe it was the family.”

So, what did the nation learn from 1968?

Many who lived through that year say they learned that it was more effective to work individually and consistently to improve society than to mass in large groups and dreamily demand wholesale, sudden change.

They learned to monitor the government, take nothing for granted, demand clear answers.

They learned to think very carefully before sending the nation’s treasure, its youth, to foreign adventures.

They learned something about the American character from men named Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and William Anders, who orbited the moon and picked up a cherished book and read these words back to “all of you on the good Earth” on Christmas Eve 1968:

“And God called the dry land Earth, and the gathering together of the waters he called The Seas. And God saw that it was good.”

They also learned something about the American character from men named William Calley Jr. in a place called My Lai and Richard Daley in a place called Chicago.

Calley once lived in Hialeah and had flunked out of Palm Beach Junior College. Now, in My Lai (pronounced mee-LIE), he was an Army second lieutenant, leader of a demoralized infantry platoon.

On March 16, 1968, Calley and some enlisted men marched into My Lai and massacred at least 109 unarmed civilians, possibly as many as 567, herding them into clearings and drainage ditches, and shooting them, up close and personal, Nazi-style.

What had we become? What was this war doing to us?

The massacre came six weeks after the Tet Offensive, when 84,000 enemy troops attacked nearly every major city and U.S. base in South Vietnam.

What were we doing here? Whom, exactly, were we helping here?

Two months after Tet, Lyndon Johnson stunned the nation:

“I shall not seek and I will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”

And then Bobby Kennedy was killed and Eugene McCarthy faltered and it was on to Chicago for the inevitable presidential nomination of Hubert Humphrey, Johnson’s vice president.

But this was 1968 and even the inevitable was unpredictable. Antiwar protesters threatened to crash the party thrown by Mayor Daley. He mobilized 12,000 police officers and 12,000 Army and National Guard troops.

He placed these common and disparate elements -- young people carrying flowers and hurling insults, young officers carrying riot clubs and bristling with frustration -- on a collision course.

They clashed, repeatedly and violently. Mace and tear gas. Hundreds clubbed senseless, including bystanders. A commission later called it a “police riot.”

The whole world is watching. The whole world is watching.

The sheer purity of this ugliness simultaneously attracted attention everywhere and repelled people everywhere. Humphrey could not overcome it. Nixon won the election.

And this was 1968 in microcosm.

And yet, and yet. . .

No one could harbor complete ill will toward a year that produced Hair, the “tribal love-rock musical” that featured nudity, high energy, nudity, precious little plot, nudity and a very commercial brand of anti-establishment fervor.

And how could anyone not fondly regard a year that produced, in addition to 2001: A Space Odyssey, movies like Bullitt, Rosemary’s Baby and The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine ?

And books like Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice or Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test .

And a range of pop songs this memorable and varied:

Hey Jude (The Beatles), Abraham, Martin and John (Dion), Wichita Lineman (Glen Campbell), Jumpin’ Jack Flash (The Rolling Stones), Hooked on a Feeling (B.J. Thomas), I’m Gonna Make You Love Me (The Temptations and The Supremes).

And, for better or worse, still the record of choice for disc jockeys in need of a bathroom break, the seven-minute, 21-second MacArthur Park (Richard Harris).

One unanswered question from 1968: Why would someone leave a cake out in the rain?

All in all, historians and sociologists agree, it was a helluva year. And we’ll never have that recipe again.

Bush, the UM history professor:

“The chaos of that year, the tragedy of that year, was just so overwhelming. When it ended, we just didn’t have much in the way of illusions anymore.”