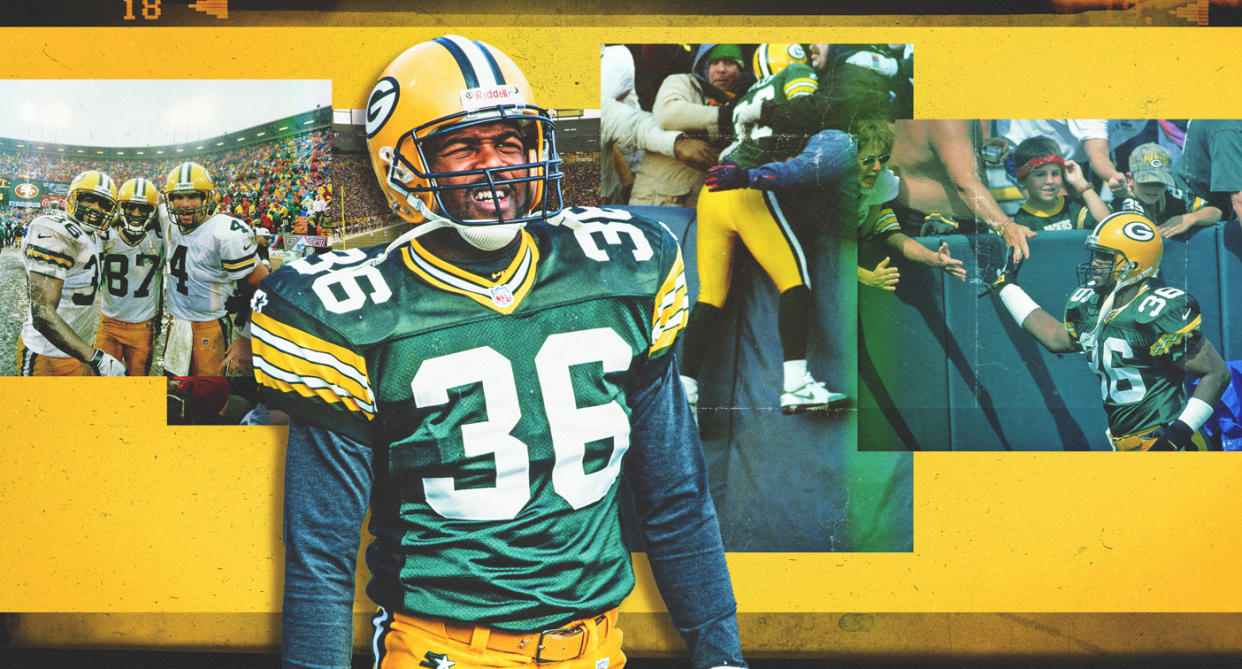

Before his Lambeau Leaps and jump into Hall of Fame, LeRoy Butler had to get out of a wheelchair

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — LeRoy Butler’s story exemplifies the quintessential sports story of overcoming impossible odds to reach professional football’s zenith: the Hall of Fame.

Rarely spotted without a smile, his bust will don a toothy grin, which he has more than earned. His formal induction into the Hall in Canton takes place Aug. 6 and is the culmination of a lifetime of persistence.

Butler played the entirety of his 12-year NFL career with the Green Bay Packers, having been drafted by them in 1990 during the second round. The prolific safety helped lead Green Bay to seven playoff appearances in nine seasons, led the team in interceptions five times and played a crucial role in the franchise’s Super Bowl XXXI victory against New England.

He also is credited with inventing the Lambeau Leap, one of football’s most cherished scoring celebrations.

Butler was a HOF finalist for the third time this year. Safeties are often hard-pressed to earn a spot in Canton, and prior to this year Butler was the only member of the NFL’s all-1990s team not in the Hall. However, Butler, made patient by life’s circumstances, knows what it is to wait out adversity.

'Why football?'

He was born in Jacksonville in 1968. Butler grew up in the Blodgett Homes housing project, which he described as crime-ridden, “poverty, humble beginnings” during a Zoom news conference with reporters last month. The first shirt he popped the tag off came from the Salvation Army, he said, and he was often bullied for wearing hand-me-downs. Butler and his four siblings were raised by a single mother named Eunice, who worked as a secretary and nurse.

He spent much of his childhood in a wheelchair because he was born pigeon-toed. Doctors had to break bones in his feet when he was 8 months old, and he sported leg braces for years. Despite this, Butler said he used to tell his mother one day he’d play in the NFL.

“Why football?” she asked him.

“It’s the ultimate team sport,” Butler said. “I can actually have 10 other guys on the field help me win a game.”

Back then no one picked Butler to play on their team at recess. By the age of 10, Butler no longer needed his wheelchair or braces, and he became the stellar athlete he and his mother knew he would be. He was recruited to play high school ball at Robert E. Lee High School, now known as Riverside, with legendary high school head coach Corky Rogers. Rogers died in 2020 at 76 as the winningest coach in Florida high school history, having won 465 games, 10 state championships and never leading a team to a losing season.

“My 11th grade year, he came to my algebra class,” Butler said. “He pulled me out of class, and I said, ‘Oh, boy.’ Because I never got in trouble. This is coach Rogers, the winningest coach in the state of Florida. He says, ‘You're playing varsity, and I want you to start, but you’ve got to play both ways because we don't have the numbers.’ And he just left. Coach Rogers was everything to me.”

While in high school, Butler earned three varsity letters in football and two each in basketball and track. He garnered All-American distinction his senior year and received ample attention from college programs. But Proposition 48 stood in the way of many offers.

The NCAA adopted Proposition 48 in 1986. The rule established a mandatory minimum GPA and standardized testing scores for athletes to be able to participate in sports their freshman year. The rule, which was replaced by the stricter Proposition 16 in the 1990s, disproportionately affected Black male athletes.

Rogers encouraged Butler to attend college, calling on him to serve as a role model for his community, particularly with a college degree.

“My senior year I remember him escorting Coach Bobby Bowden into the basketball gym,” Butler said of Rogers. “And he just said, ‘This kid just needs a chance.’”

So Rogers handed Butler off to Bowden, who Butler said would be his presenter at the Hall of Fame induction if he was still alive. Instead, Butler’s wife Genesis will take on that role.

“It made me say to myself, ‘Self, why is God choosing you to navigate these rough waters, but keep giving you great people? But you’ve got to listen,’” Butler said, reflecting on his decision to play at Florida State. He went on to earn consensus All-American status at cornerback and set a still-standing program record of 109 interception return yards in a game before joining the NFL.

LeRoy Butler's tight bond with Florida State teammate

Odell Haggins played nose tackle at FSU alongside Butler and currently serves as the team’s associate head coach and defensive tackles coach. Haggins said he could tell Butler was going to be “a special person doing special things” from the get-go. Despite having to sit out his freshman year, Butler stayed upbeat, joking around with teammates and encouraging them to play their best football.

“He never thought about himself first,” Haggins said. “He always put teammates first.”

Butler often invited teammates home with him on weekends to eat good food and play cards around his family. Jacksonville is about a two-and-a-half hour drive from Tallahassee, so those trips meant a lot to athletes like Haggins (who’s from Bartow, Florida, located about five hours from FSU) who couldn’t go home as often.

As Butler’s induction nears, Haggins said he’s elated for his teammate. As instilled in them during their playing days, the two remain like family, Haggins said. They still make sure to say “I love you” at the end of phone calls with each other.

“It means a lot for the players,” Haggins said of Butler’s Hall of Fame status. “We were on the field with LeRoy Butler. That’s an honor.”

Since retiring from football, Butler has launched a campaign called “Butler vs. Bullying,” co-authored an autobiography and launched his own liquor label, Leap Vodka.

His Hall of Fame exhibit includes a pylon and game ball from Super Bowl XXXI, his Packers uniform and a blue helmet from Lee. Butler held onto it thinking it’d be something worth showcasing, something to be proud of, he said. Now it’s on display among the most sacred of football artifacts.