Ky. has 6 Black superintendents, 171 school districts. What’s blocking more progress?

In Kentucky, a state where local school board members hire the superintendent, there are 171 public school districts, but just six Black superintendents.

The biggest challenge for Black educators in Kentucky who seek superintendent positions is the lack of opportunity, said Tony Watts of Newport Independent Schools, Greg Ross of Danville Independent Schools and Cornelius Faulkner, who retired last year as Superintendent of Caverna Independent Schools.

“We have six Black superintendents in Kentucky. When we apply for jobs, we have to ask ourselves if we truly have a chance of getting a job in that district,” Watts said in an email. “There are districts in KY that wouldn’t hire a Black person to be superintendent. It’s unfortunate, but we still have people who think that way.”

Six is the highest number of Black superintendents of desegregated public school districts that Kentucky has ever had. Many education leaders see that as a sign of improvement. Black superintendents in Kentucky say they receive support from other superintendents and education officials from across the state and from national groups.

Kentucky educational leaders, spokespersons from the Kentucky School Boards Association and the Kentucky Association of School Superintendents, say intentional efforts should be made to increase the number from six.

“I think you would be hard-pressed to find anyone among (education) stakeholders who is satisfied with the representation of Black superintendents in Kentucky’s public schools,” said Josh Shoulta, spokesperson for the Kentucky School Boards Association.

“We have to identity points in the prospective superintendent funnel where we can improve encouragement of the talented and qualified candidates that are out there, in Kentucky and beyond,” Shoulta said.

Elaine Farris, Kentucky’s first Black superintendent., sees hope in the increasing numbers.

When she was selected as Shelby County superintendent in 2004, it wasn’t a unanimous vote. It was 3-2.

“That tells you that the challenge was historical and the challenge continued,” said Farris.

“Many school boards lack diversity and board members don’t leave who they are at home when they come to board meetings,” she said.

Before she retired in 2013, Farris was also superintendent in Clark County Schools where she was hired with a unanimous vote.

“But the school board membership changed and unfortunately the newly elected board chair would not even meet with me to plan the board meeting agendas,” Farris said. “It is important that board members allow the performance and not race or gender of the superintendent to determine a fair and balanced assessment of the superintendent’s work.”

Ky.’s first Black superintendent says there are challenges, but reason for optimism

Ross, who was formerly a Fayette County elementary principal, said it takes the willingness of five school board members and “an entire community trusting that the color of a person’s skin does not limit the abilities of a qualified individual. “

Ross said he is grateful that his community and his board supported him and assured him that he had the capacity and resources to make the Danville Independent Schools district successful.

“I have had to and continue to deal with biases, intolerance, and folks wanting to do things ‘the way they used to be done,’” he said “but fortunately, I am greeted 10x more by folks that are choosing to embrace change and the opportunity for growth and wisdom in a different package.”

Shoulta said all stakeholders must continue to listen to and acknowledge the lived experiences of Kentucky’s Black educators if Kentucky is to achieve representation of superintendents truly reflective of the state’s communities.

That said, Shoulta said, “we’re not aware of any instances of school boards -- or the district-wide superintendent screening committees that make recommendations to the school boards -- passing over qualified candidates on the basis of race.”

The other four Black superintendents in Kentucky are Demetrus Liggins of Fayette County Public Schools; Diane Hatchett of Berea Independent Schools, Alvin Garrison of Covington Independent Schools and Patrice Chambers of Fulton County Schools.

Garrison said he sometimes faces a challenge as a Black superintendent because someone thinks “you might treat them unfairly because they are not the same color as you.”

“But for the most part, I’ve had a great run here in Covington,” Garrison said of the nine years he’s been superintendent.

Hatchett, named the Superintendent Commission Chair of the National Alliance of Black School Educators, has had a similar experience in Berea, with only occasional instances of explicit racism.

“Being a minority superintendent isn’t easy but I consider it a blessing and honor and a privilege that I take seriously,” she said.

Hatchett said when it comes to race, “some things are out in the open, others are subtle, covert.”

Hatchett said people have sent her “very nice notes based on race. “

“I have had some people send me not so nice notes,” she said. “They have even brought my family into their comments. These types of things are few and far between and always anonymous which is cowardly.”

Fayette an exception

Education Week has reported that 6.1 percent of teachers in the United States are Black, compared to 79.9 percent who are white. Nationally, 10.4 percent of principals are Black, compared to 77.1 percent who are white.

The 2021–22 American Association of School Administrators School Superintendents Association has a Superintendent Salary & Benefits study, released in February 2022, based on 1,776 complete responses.

Approximately 87% of respondents identified as White, followed by 4% Black or African American, and 3% Hispanic or Latino.

Hatchett said that while six superintendents is a low number, it’s the most Kentucky’s ever had.

Kentucky had Black superintendents in the days of segregation, according to the University of Kentucky’s Notable Kentucky African Americans Database.

Jim Flynn, executive director of the Kentucky Association of School Superintendents, said Kentucky didn’t have the first Black superintendent of a desegregated district until 2004 when Farris became Superintendent of Shelby County Schools.

Fayette County Public Schools has been one of the exceptions in the state in that the district has had a Black superintendent, acting or permanent, for about the last nine years.

Demetrus Liggins replaced Manny Caulk who died after a brief illness in 2021. Marlene Helm has served as interim superintendent in Fayette County three times over the years.

Liggins said in Fayette County Public Schools diversity, inclusion and belonging are core values.

Watts, who formerly worked at Central Office in Fayette County, said the state needs to do a better job of creating a more diverse pool of applicants and make it a priority to hire more minority superintendents.

“It’s important for students of color to see someone who looks like them in leadership positions,” Watts said. “If students see superintendents that look like them they may be more likely to pursue that career. We want to have as much diversity as we can so our students can see various people in various roles.”

Garrison said it’s important for students to be exposed to superintendents of color. It breaks down “stereotypes and biases,” he said.

Representation matters, said Liggins. He said that the Kentucky Association of Schools Administrators is working to encourage diversity and inclusion in multiple groups and to train the next generation of leaders.

He said it’s not just important for Black students to see Black superintendents: “It’s important for all students to see that diversity.”

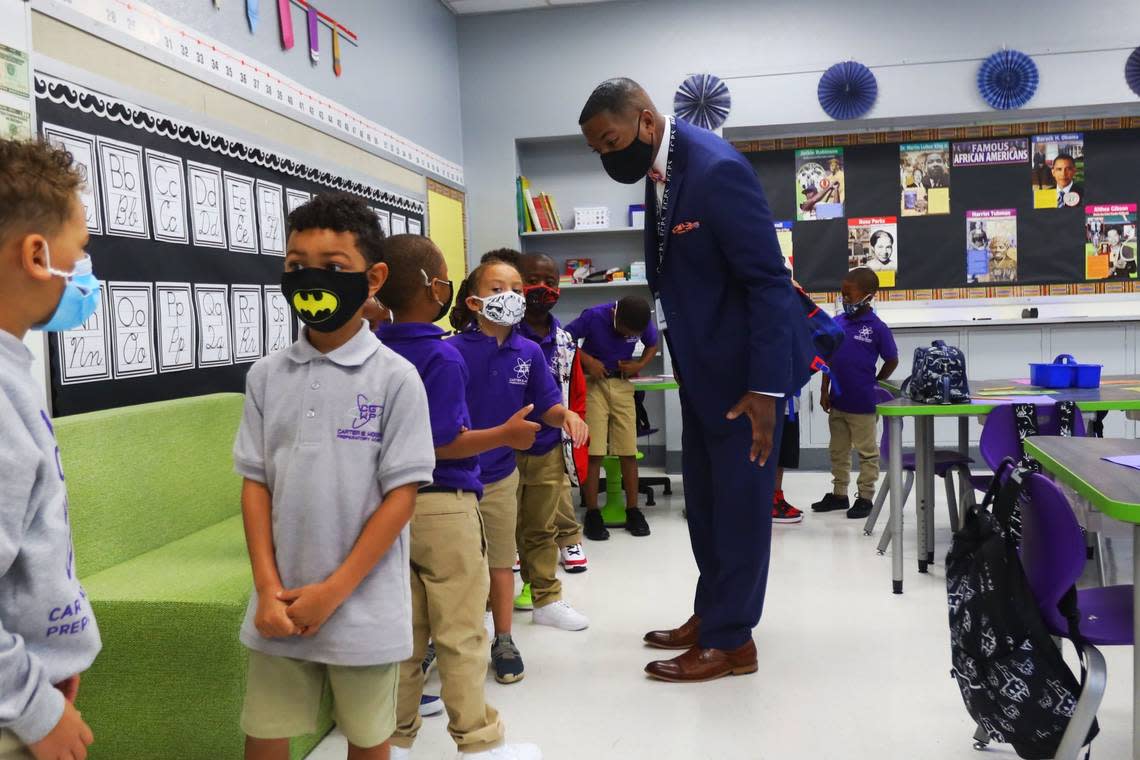

Liggins said when he was growing up in the late 1980’s and 1990’s, if a Black superintendent had walked into his classroom, “I would have been in awe of having someone in that role. It would have shocked me.”

When he walks into Fayette classes now, he said students are accustomed to seeing leaders of various backgrounds.

“I think we are definitely making progress in general,” Liggins said.

Liggins noted, though, that the diversity of Kentucky superintendents is not representative of the population.

Black students represent 10.8 percent of the total public school student population in Kentucky, according to Kentucky Department of Education data for the 2021-2022 school year.

“We want the best people leading our students, regardless of their race or how they identify,” said Liggins. “All things being equal, if you can diversify, that’s all for the better.”

‘We are all standing on someone’s shoulders’

Shoulta said the hiring of a superintendent, one of the most important decisions of a local school board, represents the final stage of a long process.

Extensive training, mentorship, and recruitment and retention moves qualified superintendent candidates to a point in that process and requires action by a number of “stakeholders.” The stakeholders include postsecondary institutions, the state Department of Education, the professional associations for educators and administrators and policymakers, he said.

Flynn thinks Kentucky is building capacity to have more potential minority superintendents. But he said consideration might need to be given to bringing back a Kentucky minority superintendent training program that was discontinued a few years ago or something like it.

Ross said that when he was a Kentucky Department of Education director, he wanted to keep the Kentucky Minority Superintendent Internship Program that no longer exists.

Garrison and Hatchett found a job as a superintendent within a year of leaving the program, Ross said. Garrison said he doesn’t think he would haven’t gotten his opportunity in Kentucky without having the program on his resume.

Toni Konz Tatman, spokesperson for the Kentucky Department of Education, said the program was discontinued in 2017 under an agreement with the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights that had issued a letter to the state education department saying such programs were unconstitutional based on their use of race.

Tatman said the initiative under which the internship program operated has transitioned into the Kentucky Academy for Equity in Teaching program.

Even when Kentucky had the Kentucky Minority Superintendent Internship Program, Watts said, the state still didn’t have a lot of Black superintendents.

“I think it still comes back to opportunity. By having a program, will that change a district’s mindset about hiring a Black superintendent? I’m not sure,” Watts said.

On a national level, there are opportunities for aspiring superintendents to participate in workshops and summits, Hatchett said.

In Kentucky, Black superintendents and other superintendents support each other.

Hatchett said, “We are all standing on someone’s shoulders... as an African American female superintendent I stand on the shoulder of giants.”

Many active and retired superintendents are serving as mentors to aspiring superintendents and are willing to answer questions, provide resources or support, constructive feedback, and contact information, said Hatchett, who was the first Black female superintendent in her district.

As a first year superintendent, Ross said Matt Moore, Superintendent of Jessamine County Schools, Will Begley at Burgin Independent and “an entire fraternity of superintendents” have helped him along with other education leaders across the state.

Fellow Black superintendents including Garrison, Hatchett, and Watts reached out to him immediately as did Liggins, who “has always been a text message away,” Ross said.

Chambers said she received support from superintendents across the state. Chambers said she is “extremely proud” to be the first Black superintendent hired in her district and one of two Black female superintendents in the state.

Chambers said “race doesn’t factor into my day-to-day job.”

“Although I am very proud of my heritage, I do not believe that race determines my effectiveness as a superintendent,” Chambers said. “I work hard each day to make sure that our students and staff get the best version of me. I am just a superintendent who happens to be Black. I want to be seen as a person who works hard and makes decisions that will benefit our students regardless of my skin color.”

Ross said he’s “well aware” of the opportunity he has in Danville Independent Schools.

Outside of that, Ross said the problem of bias “is so much bigger than the field of education,” that he feels a responsibility to help all people who are overlooked or refused opportunity.

“We have folks making financial choices, career choices, educational choices, political choices and so much more based on their explicit bias and feel validated in doing so,” Ross said. “The work doesn’t begin or end with me being in a position of authority unless I am willing to advocate for change for all, not just myself.”