70 years later, Korean Americans are still working to formally end 'The Forgotten War'

Hannah Lee, a college student who’s attending a gathering Thursday in Washington, D.C., to call for a real end to the Korean War, says she remembers the first time the conflict was mentioned at her public school in Tacoma, Washington.

“In sixth grade, my teacher told me that the Korean War was over. But I knew from my parents that the war had never officially ended,” the activist and rising junior at the University of Pennsylvania said.

In commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Korean War Armistice, hundreds of advocates are gathering in the nation’s capital to take part in a mobilization to formally end the conflict. The multiday event is supported by a range of U.S.-based peace organizations and will include a congressional news conference with co-sponsors of H.R. 1369, a House bill calling for serious diplomatic efforts toward a permanent peace agreement in Korea.

The Korean War, sometimes called “The Forgotten War” in the United States, was only a small footnote in Lee’s history books at school. “I realized later that the war played a huge part in the United States’ extensive military involvement abroad,” Lee said. “It’s important that younger activists like me increase public awareness on how devastating the lasting effects of the war have been across generations.”

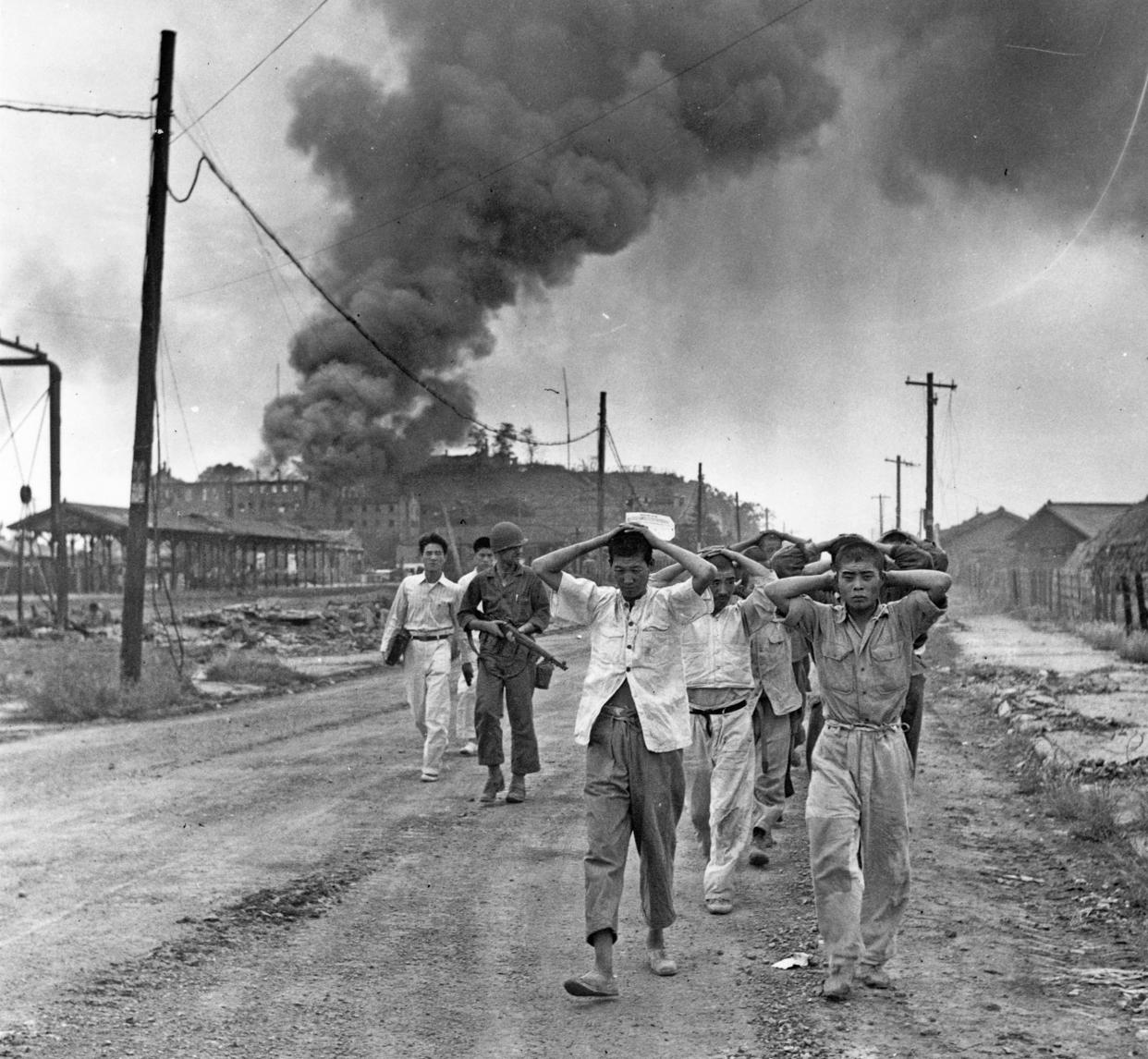

The Korean War began on June 25, 1950, when North Korean forces invaded South Korea. The Soviet Union and China trained and aided North Korea, while the U.S. supported South Korea with United Nations-backed forces. The war was a proxy for these larger powers and became the first military action taken during the Cold War.

The Korean War Armistice was signed on July 27, 1953 by representatives from the U.S., North Korea and China. South Korea, intent on reunifying the two Koreas, refused to be a signatory of the truce. The following year, there was an attempt at the Geneva Conference to broker a peace deal, but the negotiations fell apart.

The armistice was originally meant to serve as a temporary agreement while the parties reached a permanent peace treaty within three months. Seventy years later, the conflict remains unresolved and is the longest-standing conflict in which the U.S. has taken part.

Political support for a peace agreement has slowly but steadily grown over the years within the U.S. On the 60th anniversary of the war, in 2010, only two members of Congress publicly supported a peace treaty. This year, H.R. 1369 was reintroduced to Congress with 33 co-sponsors and has been referred to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

“This year’s mobilization is unprecedented. Nothing in recent U.S. history has been organized of this scale, with so many diverse voices calling for peace,” said Christine Ahn, who in 2015 led a symbolic crossing of the Korean demilitarized zone, a border barrier dividing the peninsula.

The 70th anniversary of the armistice comes as the nuclear-armed North, formally known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, has been ramping up weapons-testing, including of ballistic missiles capable of reaching the continental U.S. North Korea has said the tests came in response to the enhanced military cooperation between the U.S. and South Korea, formally known as the Republic of Korea.

Denuclearization talks with the North, with which the U.S. has no official relations, have been stalled since 2018. The Biden administration says it stands ready to negotiate with North Korea without preconditions.

The State Department said in a statement to NBC News, “We continue to consult closely with the Republic of Korea, Japan, and other allies and partners about how to best engage the DPRK, deter aggression, and coordinate international responses to the DPRK’s violations of multiple U.N. Security Council resolutions. The United States harbors no hostile intent toward the DPRK.”

Neither the South Korean government nor the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Mission to the United Nations respond to requests for comment.

Another issue at stake is the travel ban to North Korea instated by former President Donald Trump in 2017, rendering North Korea the only country Americans are prohibited from entering. The U.S. has the largest population of Korean nationals overseas, so the travel ban prevents Korean Americans from visiting family in North Korea.

The Biden administration has upheld the ban despite campaign promises to reunite Korean families. Addressing the restrictions, the State Department said that “the decision to renew the geographic travel restriction … was made after careful consideration, taking into account that the State Department has no higher priority than the safety and security of U.S. citizens overseas.” The administration recently worked with the United Nations and Swedish officials to determine the status of U.S. Pvt. Travis King, who fled across the demilitarized zone to North Korea earlier this month.

A new generation seeking closure

Hana Marie Kim, 14, is an actor and activist based in California who is protesting the travel ban as a fifth-generation member of a divided family. Kim’s great-great-grandfather was a social reformer who traveled to what is now North Korea in 1948 in an attempt to help reunify the Korean Peninsula after it was split between the U.S.-occupied South and Soviet-occupied North at the end of World War II. After the borders closed, he was never able to see his family members again.

Kim expressed a desire to travel freely to North Korea if the travel ban is lifted. “I hope to visit my great-great-grandfather’s gravesite and meet my North Korean relatives one day,” she said.

Cathi Choi, the director of policy and organizing at Women Cross DMZ, a women-led group advocating peace in Korea, noted the importance of the young Korean Americans in the effort.

“So much depends on the Korean diaspora in the U.S. As American citizens, we get a say in how our elected representatives spend our military budget. We can engage with our democratic systems to demand an end to this war,” Choi said.

Kee Park, a neurosurgeon and lecturer at the Harvard School of Global Public Health, has traveled to North Korea 18 times on humanitarian medical missions but has not returned since the travel ban was put into place. Park described the large pieces of inoperable equipment he saw when he volunteered in North Korean operating rooms. Because of harsh sanctions, hospitals were not able to repair and maintain basic machines like X-rays and ventilators.

Park said establishing peace is a necessary requirement to build an effective public health system in North Korea. “The absence of peace is the worst thing that could happen to the health of a population. North Korea needs the ability to access outside knowledge and interact with international medical staff. There is a huge outcry from the development community to make humanitarian work viable there,” Park said.

Deann Borshay Liem, a Korean American adoptee and filmmaker whose latest documentary, Crossings, followed the 2015 DMZ crossing, said her goal is to educate people through her film and shift dominant narratives about the war. Liem sees her adoption case — along with the cases of 200,000 other Korean children sent overseas — as a microcosm of the millions of family members who were divided during the Korean War, even within the peninsula.

“Through my filmmaking, I came to understand that my adoption happened in the context of war and division. The irresolution of the war and the continued militarization of the Korean Peninsula resulted in a society that couldn’t support families in need,” Liem said.

For longtime activists like Ahn, the 70th anniversary is a crucial moment to challenge the status quo. “We’ve had enough of the establishment’s definition of security. Their approach has not worked. The threat of nuclear war, the division of millions, humanitarian crises — this is not deterrence, this is violence,” Ahn said. “The U.S. has a moral responsibility to finally end the war.”