I Knew I'd Fail at the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament. That Was the Point.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

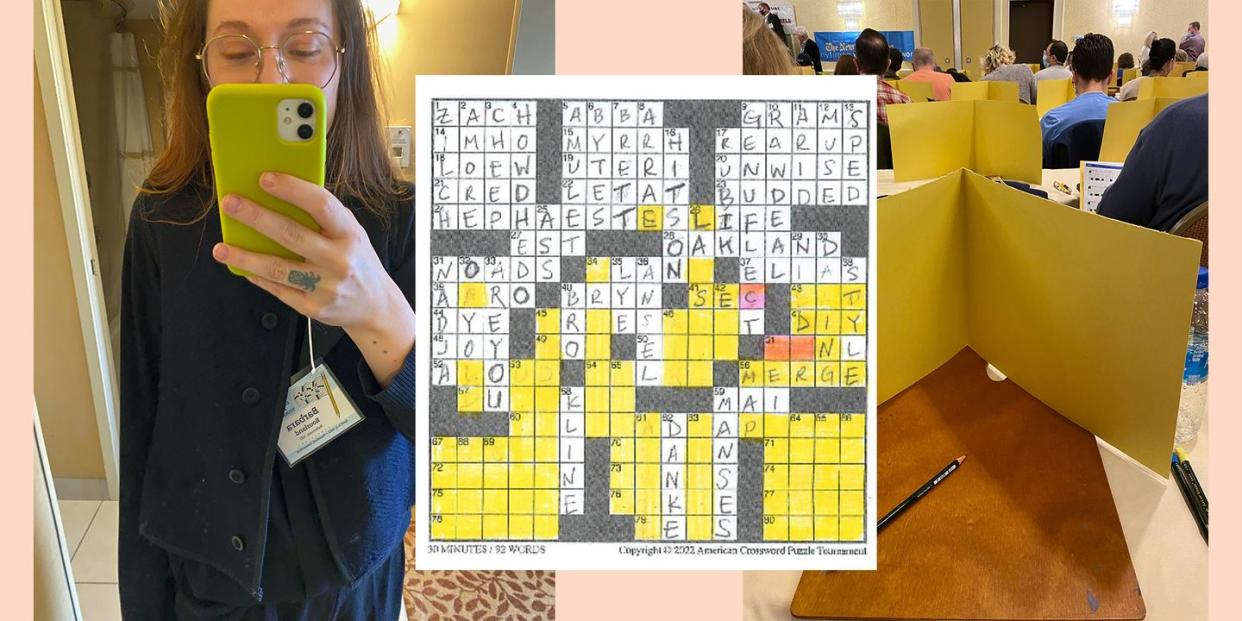

I’m in a hotel ballroom in Stamford, CT, surrounded by 500 people, and everything in my body is telling me to leave. My hands are shaking, my stomach is roiling and under my mask, my skin is turning beet-red from nerves. I’m in this state of abject terror because I’m about to knowingly destroy my relationship to something I’ve loved deeply my entire adult life. I’m a rookie at the 44th annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, and I came here to fail. On purpose.

The night before, I’d asked ACPT director Will Shortz, the longtime editor of the New York Times Crossword Puzzle, what advice he might have for a rookie like me. “Make sure you fill in all the letters,” he replied. “That’s a really common mistake.” At the time, I’d wondered if that — like the fanfare about the difficulty of Puzzle Number 5 — was perhaps a bit of a joke. But now that I’m sitting here, it seems very possible that not only could I forget to fill in some of the letters, but that I might forget every word I’ve ever learned, too.

The tournament consists of seven puzzles over two days, followed by a championship round for the highest-ranked. Each puzzle is allotted fifteen to forty-five minutes, depending on size and complexity, and our paper grids will be scored for accuracy and speed. The first puzzle is handed out, face-down. After several delays — someone spilled a coffee, a lefty needs a second puzzle — Will finally says “go.”

Five-hundred pieces of paper are turned over at the exact same moment. The sound ruffles gently through the ballroom, and I bow my head, press a trembling pencil to paper and start solving.

Eleven minutes later, I raise my hand, turn in my puzzle and walk out. Hallway small talk reveals within seconds that I’ve made a mistake, flubbing the abbreviation for “Postal HQ” and surprisingly, so did a lot of other people. “I only knew the right answer,” a woman later tells me, “because my husband was a postmaster.”

I wait for my heart to fall; for the familiar feelings of disappointment and embarrassment to take hold. Yet, there is only joy. Still, there’s six more puzzles to go. Six more chances to fail and to feel shame, and six more opportunities to change my reaction to failure by sacrificing something I love.

I needed to balance my self-worth and ambition

Over the past several years, I’ve been undergoing a one-woman experiment to discover if I can extricate my sense of self-worth from my ambitions. Thus far, the drive to succeed has influenced the course of my life above else. My partner and I have, time and again, put work first, changing cities, homes and communities as our professions demand. And we’ve achieved a lot.

But, as so many of us learned during the pandemic, when a person’s professional life becomes their entire life, their self-esteem depends on its wins, and becomes pathologically averse to its losses. During the publication of my first two novels, I believed I was old enough, and had done enough therapy to understand what it meant to submit yourself for a performance review in public. Naturally, I was wrong: instead of responding with grace, I observed, with horror, as my standard for regular, go-about-your-day-self-worth became "ecstatic praise from others." Anything less was a catastrophe, one that left me feeling trapped in the double-bind of resenting myself for failing and for feeling like a failure, too. When your minimum for “OK” becomes “be the best,” it’s impossible to have a healthy relationship to anything, or anyone. Most of all, I felt like I'd lost my sense of joy. And I wanted it back.

I initially tried to manage this with the obvious: talk therapy. CBT. CBD. Meditation. Running. Drinking. Not drinking. All of these things worked until they didn’t; they were fine Band-Aids, until they fell off. The deeper problem — that my sense of self was fused to my ambitions — couldn’t be solved by breathing exercises, so I did the only other thing I know how to do: I wrote about it.

Using the desire to be special to drive the emotional tone of my third novel, The Force of Such Beauty, I worked my way through the problem until I understood that ambition was a core part of my identity, one that that I probably couldn’t change. But I could change what I was ambitious for. If I could move my focus from outcomes to experiences, maybe I’d finally understand that winning was for suckers, and participation trophies were the most valuable things I could earn.

Exposure therapy could acclimate my brain to failure

Unfortunately, my brain continued operating under the same conditioning I’d always given it: ambition meant fear and adrenaline, followed by stratospheric reward or paralyzing shame. Months passed as I continued to have the same reactions to the same problem. But I had one final arrow in my quiver: CBT’s theory of exposure therapy, a technique that uses a safe practice of the exact thing we’re afraid of in order to change our reaction to it. I started exposing myself to failure. I started easy, with a footrace I knew I wouldn’t win, and after I bombed that, moved on to applications to fellowships and grants that my cynical mind told me I had no chance at receiving. The failure piled up; the rejections rolled in. I found every challenge getting easier. It was working, but it didn’t seem like enough. The stakes had to be higher or my brain wouldn’t learn. That left one beautiful, pure, therapeutic, private, personal thing.

Crosswords.

The year I was 21, I lost my home in an electrical fire, and experienced the death of two extremely close friends: my roommate and a recent ex-boyfriend (both tragic, both unexpected, and unrelated to each other and the fire). Though my experience of loss was not unique, I was young enough that it was unusual, and as a result, extremely isolating. I didn’t know how to let go or say goodbye; I didn’t know how to move on. As I struggled to breathe in the undertow of so much grief, I mostly sat alone in my room and did hundreds of New York Times crossword puzzles. Within the confines of the grid, I was protected from the hard realities of chaos and tragedy. I remember ripping out the puzzles when they were complete and watching them flutter across the floor, as if I was papering my life back together. Reducing my thoughts to a single set of clues and answers brought peace and comfort when nothing else did. It brought me back to the world.

Since then, I’ve done puzzles almost daily, even constructed a few and submitted them to the Times (rejected, but with more feedback and care than I’ve received from most editors in my career). I’m good at it, for a regular person. At the most competitive tournament in the nation, though, I’m a guaranteed loser.

This time, failing publicly didn’t break me

In Stamford, waiting for the second puzzle, my anxiety is somehow worse. What if that post office question was a fluke? What if this time I fail where everybody else succeeds? I try to comfort myself by noting that it feels exactly like getting an email from a publicist with a new review of my book enclosed. If I feel this bad, I’m definitely on the right track.

The timer starts, and we’re off. This time I notice that hands go up three, four minutes in. These are the champions, the speed solvers who will face off at the final championship round tomorrow on gigantic whiteboards, as shown in the documentary Wordplay. I can’t fathom how they can complete the fill so rapidly, much less read the clues.

It turns out they don’t. A music teacher ranked 40th — this is extremely high — later tells me that he only reads about a third of the clues, then deduces the rest with a combination of experience, instinct, and the NYT’s specific crosswordese.

But the flood of champion hands doesn’t bother me, and the clock doesn’t trip me up, either, although this one is harder, with 25 minutes allotted. I’m too busy solving, going up again and again into the space between clue (“Landlocked African nation”) and solution (Mali). I’m high on the drug of a collective consciousness. It feels like someone took the essence of a library, turned it up to 11, and scattered it over us with a magic wand. It feels like heaven.

After that, I don’t wonder if I’ve made any errors. I don’t care. I’m simply happy to be here.

Even the pros cheered on my efforts

The ACPT Rookie FAQ had provided a fair number of important tips — bring a clipboard because the tables have tablecloths; don’t wear perfume because some people hate it — but it turns out the most salient piece of advice was the very end: “TL/DR: people are friendly.”

People were better than friendly; they were sincerely excited to be among kindred spirits. I had a moving conversation about grief with a scientist whose specialty is the moon; I got a pep talk about rejection from the youthful editor of Spelling Bee, Sam Ezhersky, who has been publishing puzzles in the Times since he was a teenager. Once people hear I’m a rookie, their eyes get kind, and they tell me that it’s so good that I’m trying. Nobody means this in a condescending way. I learn in the final tally that out of 500 cruciverbalists (the preferred phrase) who enjoy doing crosswords enough to travel to Connecticut and stay in a broken-down Marriott for an entire weekend, only 32 will complete all seven puzzles without making an error. The margins are narrow, even for the pros.

Puzzle 5 is, as advertised, devastating, and I only complete a quarter of it. Puzzle 6 is a digestif, a satisfying end to a full day. I take myself out to dinner at the steakhouse across the street and strike up a conversation with another competitor, nervous to be alone in my hotel room with only my self-consciousness for company.

But when I go to sleep, all I can think is that I can’t wait to be in the ballroom again. Life is short and full of trauma. I want to experience these days of comparative peace and plenty with every ounce of my being; I want to be present, to live the gift of my life without wishing for it to be different. I want to be in the mix, for better or worse. After the 7th puzzle, I come in 46th out of 117 rookies, squarely in the middle, a sign that I was there.

On my train ride home, all I feel is grateful. The next morning, I hang my ACPT name badge in my office. Then I log in to the Times and tackle the day’s puzzle. Accepting that winning was impossible didn’t ruin my relationship with crosswords. It only deepened it, and I can’t wait to go back another year and fail again. I think my experiment might be working.

Barbara Bourland is the author of Fake Like Me, a finalist for the 2020 Edgar Award for Best Novel. Her third novel, The Force of Such Beauty comes out in July 2022. She lives in Baltimore. This essay is part of a series highlighting the Good Housekeeping Book Club — you can join the conversation and check out more of our favorite book recommendations.

You Might Also Like