In killing plot from jail, Fort Worth Crips gangster who stirred terror sentenced to life

The black Chrysler 200 was parked for 11 minutes on Belshire Court as the sun lowered in the sky.

A woman whose thoughts were clouded by weed was in the driver’s seat. In the back, Damond Cotton was ready with a rifle that was attached to a device that would soon catch ejected cartridge casings that would be cast like popcorn kernels from the gun.

Through the windshield they could see across to a house in Fort Worth, near the city’s southern border with Everman, where Cotton’s target lived.

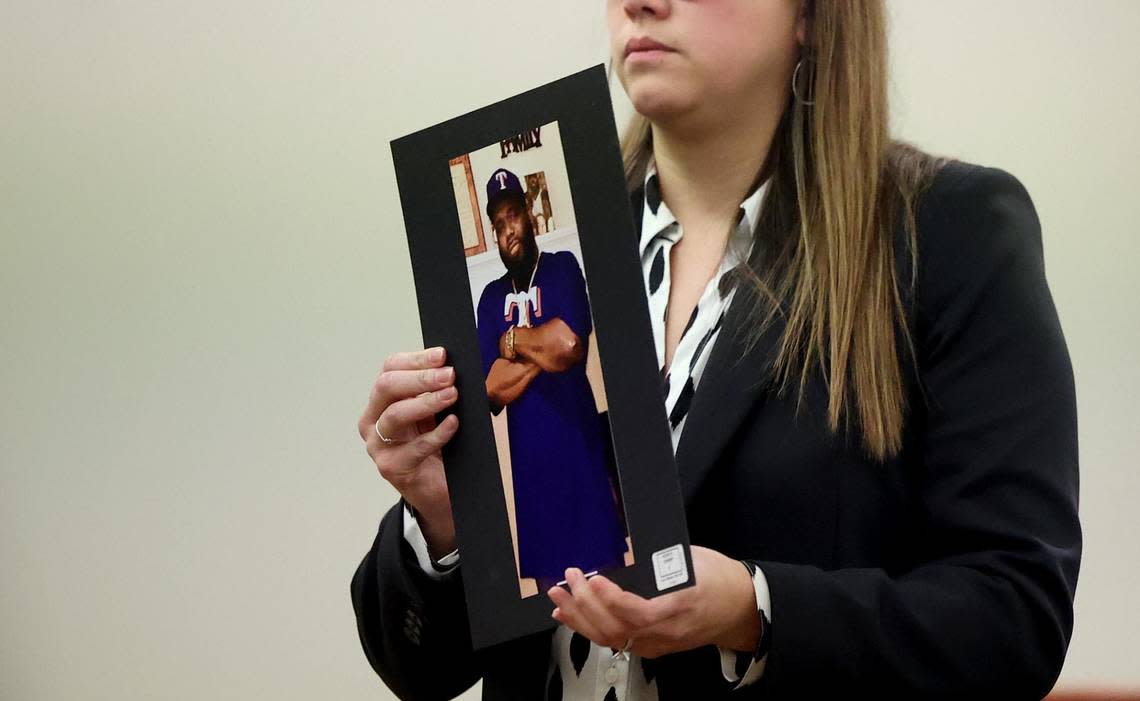

Kevin Brown Sr., who was 47, walked with a cellphone down his driveway to a mailbox encased in a brick column and peered inside.

He withdrew nothing, closed the door of the mailbox and stood beside it, the phone to his ear.

The sedan’s driver steered around the corner and slowed. Cotton leaned from the rear passenger-side window and released a torrent of riflefire. Brick particles floated in the air. One of the rounds tore into Brown’s head.

Today's top stories:

→ Fired Fort Worth principals accused of fraud, racist comments, sexual harassment

→ Mom, daughter fear for safety after man accused of sexually assaulting them is released

→ 2-year-old Fort Worth girl attacked by pit bull in CPS custody

🚨Get free alerts when news breaks.

Blood spread from his body stretched near where the driveway meets the street. Next door, a neighbor paused working in his yard as the car from which Cotton fired took off.

At first, the police theorized that Brown was killed because of his son, Braylin Brown. He was, although not in the way homicide detectives initially thought.

Braylin Brown, documented by Fort Worth police as a Crips street gang member and monitored as a person connected to the Rolling 60s, one of 38 Crips sets in the city, feuded with members of other gangs and was a possible target of violence. In jail on Jan. 25, 2022, the day of his father’s killing, Braylin Brown was inaccessible. His relatives, however, were available to people who meant him harm.

A neighbor’s surveillance camera recorded the assailants’ vehicle. Its right fender and back right tire were damaged. An officer in the police department’s Real Time Crime Center reviewed images of license plates attached to similar vehicles spotted by a network of city-operated cameras. The officer found a possible match, and the registered owner then led police to the driver, Ashlynn Durham, and to Cotton, her boyfriend.

When police executed a search warrant at an apartment where Cotton lived, they found handwritten letters that detectives believed Cotton wrote to Braylin Brown. The letters suggested a friendly relationship between Cotton and Braylin Brown, and led Fort Worth police homicide Detective Michael Sones to a new theory. Perhaps Braylin Brown wanted his father dead and arranged for Cotton to kill him.

The slaying’s motive, prosecutors argued, was found in a secret sexual relationship Kevin Brown Sr. had with Rebecca Willis, who also had such a relationship with Kevin Brown Jr., Braylin Brown’s brother.

Willis had a child with both men. (Kevin Brown Jr. was shot to death during a robbery attempt.)

Willis, who was at Kevin Brown Sr.’s side when the first officer arrived, falsely told the officer that Brown Sr. was her father.

The scandalous affair, in which two men shared a name and a sex partner, meant that his father was “grimey,” Braylin told others.

The letters from Cotton suggested the homicide’s motivation was far more horrid than the initial retaliatory drive-by explanation.

Detective Sones concluded that Braylin Brown, from the Tarrant County Jail, had ordered a hit on his father.

With jail tablet messages and phone call records, prosecutors presented evidence they suggested showed Braylin Brown discussed in coded language how the killing was to occur and instructed a girlfriend to buy bullets and get them to Cotton. In the messages, Brown referred, for example, to a gun as a controller and ammunition as pieces of the controller.

In a three-way phone call, Braylin Brown, speaking from the jail in the seconds before his father was shot to death on Beacon Way, urged him to check the mailbox.

A jury in the 396th District Court in Tarrant County on Wednesday sentenced Brown to life in prison. Last week, in his trial’s guilt-innocence phase, it found the 22-year-old defendant guilty of murder in his father’s death under the law of parties that holds a person criminally responsible for the conduct of another person if the defendant solicits, encourages, direct or aids the other person to commit an offense.

The sentence appears to have closed a violent criminal spasm in Fort Worth for which law enforcement authorities allege Braylin Brown is responsible. He was indicted in two other homicides. Beyond those killings, prosecutors alleged he shot a grandmother in the arm as he intended to fire upon someone else and fired a gun at a man outside a convenience store in the Como neighborhood.

“He is a hardened, violent gang member. That’s what he is,” Tarrant County Assistant Criminal District Attorney Katie Owens said in a closing argument in the trial’s punishment phase.

“You have the power to end the carnage,” Owens told the jury.

Durham, the driver of the Chrysler 200, said from the witness stand she learned from Cotton that Braylin Brown agreed to pay Cotton $3,000 for the shooting. Law enforcement authorities did not seek a capital murder indictment underpinned by evidence that the victim’s killing was purchased.

“I can’t prove money was exchanged,” Detective Sones testified.

Dr. Kendall Crowns, the chief Tarrant County medical examiner, conducted Kevin Brown Sr.’s autopsy. Crowns told jurors he used his fingers to push on Brown’s brain to expose bullet fragments he wanted to collect.

The trial took place over parts of eight days. Owens presented evidence with Tarrant County Assistant Criminal District Attorney Matt Rivers. Defense attorneys Steve Gebhardt and Brian Eppes represented Brown.

The jury deliberated on the sentence for about three and a half hours. It considered a term of between 15 and 99 years or life.

Though law enforcement authorities concluded Braylin Brown arranged his father’s killing because of a romantic partner choice, the defendant’s motivations in other violence were connected to grievances he held with people he perceived as snitches or who were otherwise disloyal. He terrified acquaintances and strangers whose cooperation with law enforcement investigations may have imperiled his freedom, authorities allege.

Defendant takes the stand

Brown had decided not to testify in the trial’s first phase, but changed his mind on the morning the defense began to present its case. The jury, during its first deliberation, would not have known of Brown’s gang membership or alleged involvement in other crimes had he stuck to his original plan.

Brown denied planning his father’s death. His jail tablet messages included discussions of robbery of a man named Mohamed, the defendant testified.

Owens, the prosecutor, asked Brown why he wanted Mohamed robbed.

“Because he had money,” replied the defendant, who said Mohamed was the “African monster” he wrote of in the messages.

On the witness stand, Brown suggested the allegation that he set up and paid for his father’s killing was absurd.

“I didn’t even have $3,000,” he said.

The defendant testified that he did not learn of Willis’ relationship with his father until after his death.

“I don’t kill innocent people,” Brown said.

Owens asked the defendant whether he had killed anyone.

“Somebody try to kill me, I’m going to kill them,” Brown said. “Somebody hurt my family, I’m going to kill them.”

“I’m asking you. Have you killed someone?” Owens pressed.

“I’ve never killed nobody in my life,” the defendant said.

Brown acknowledged he had been a Crips member, but left the gang when he gave his life to God.

Owens asked the defendant whether he was involved in the drug overdose death of his mother.

“Did you give her the drugs?” the prosecutor asked.

Brown, a rapper known as “Crazyboybray” released a song on Nov. 21, 2022, while he was in jail.

In “Criticizing,” Brown says, “the last [expletive] that played me, his [expletive] was found in the yard,” which prosecutors said refers to the killing of Rashad Johnson on May 11, 2021, in which they alleged Brown shot Johnson in a drive-by, leaving him to die in his front yard.

After the guilty verdict in Kevin Brown Sr.’s death, prosecutors presented to jurors evidence of Brown’s involvement in the Johnson homicide, including the testimony of a man who said he drove a vehicle in which Brown was a rear passenger and, outside Johnson’s house, heard gunshots from that location in the vehicle, implying that Brown fired the shots.

Owens asked Brown to explain references in the song. In order to explain, Brown rapped from the witness stand.

As court reporter Lisa Morton furiously typed, Judge George Gallagher interrupted the defendant.

“You’re going to have to slow down,” the judge said. “I know you’re trying to get into your deal, but the court reporter’s got to keep up.”

Braylin Brown’s defense attorneys argued the motive the state suggested in his father’s killing did not make sense. Their client was actively working with his father to gather money for a bond so that he could be released from jail.

Defense attorney Gebhardt noted to the jury that prosecutors did not play recordings of Brown’s jail telephone calls.

“It is my understanding that they don’t record calls,” Detective Sones testified of the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office.

Gebhardt observed that jail authorities have the capacity to record inmate calls.

Cotton, Durham and Alexis Abeyta, who testified she purchased bullets at Brown’s direction, have been charged with murder in the homicide of Kevin Brown Sr. The cases have not been disposed, and Gebhardt suggested Durham and Abeyta could expect strong deals, including, perhaps, dismissal. Durham and Abeyta testified that the state had not promised anything in exchange for their testimony.

Killer rejected plea deal for 50 years

In February, Brown stood before Judge Gallagher to announce whether he wanted to accept or decline a plea deal from the state that would cover all of his pending cases.

“Your Honor, at this time the offer is 50 years on those cases. Those would run concurrent,” prosecutor Owens said as she stood near the bench.

After he explained an arrangement known as a plea in bar, Gallagher suggested it was time for Brown to decide.

“So do you want to take it or are you ready to go back?

“The other thing you need to think about is at your age this would put you back in control of your life, and it would be up to you to be able to behave in order to get parole. I can’t tell you how long parole would take. I can tell you on a 50-year sentence, you’ve got to do 25 years flat. But you’ve done how long? How long have you been in jail?”

“Two — two years,” Brown answered, with defense attorneys Eppes and Brian Salvant at his side.

“All right. So you’ve got two years off that — you’ve got two years off that 25. So that would mean 23, potentially you’d be 45 when you get out versus I’m going to die in prison. But I can’t promise you’d get out at 45. That’s up to the folks in Austin. Nobody here has control over that. You’re the one in control of it. If you don’t get in any trouble down in [a penitentiary], the likelihood is as young as you are, you’ll get paroled.”

Brown struggled with his choice.

“I ain’t going to lie, it’s hard,” he said.

“I’m sorry?” the judge replied.

“I said, ‘I ain’t going to lie, it’s hard,’” Brown said.

“It is hard. It is hard. I tried the case against Mr. Robinson,” the judge said of Adrian Robinson, who shot to death a 17-year-old girl to win notoriety and respect within his gang and was found guilty in October 2022 of gang-murder and gang-deadly conduct in the rifle killing of Cheyenne Moore.

“I know you did,” said Brown, who also was indicted in connection with Moore’s killing.

“I gave him 75, “ the judge said. “And I think you’ll hear that I’m not real — I try to be fair in punishment. But it’s some bad stuff that y’all are accused of doing,” Gallagher said.

“Twenty-five years is a long time,” the defendant replied.

“It is. I agree,” Gallagher said. “But you’re rolling the dice. And again, I’m not trying to force you to do something that you don’t want to do. I’m just telling you, here’s what the deal is. And I need a decision.”

“I’m going to reject the deal, Your Honor,” Brown said.

Thirteen days later, according to the district attorney’s office, Brown threatened to kill Salvant. The defense attorney withdrew from the case.