Kids outnumber adults at KC domestic violence shelters. Can they break cycle of violence?

Sophia’s child called her Wednesday, eager to talk about the day’s summer camp trip to the swimming pool, complete with a slide and a basketball net. But the most important words came next:

“Mommy, I feel happy.”

Sophia, a survivor of domestic violence and mother to two elementary school-age kids, moved into Newhouse, Kansas City’s first domestic violence shelter, about a year ago. The Star is using a pseudonym to protect the survivor’s identity. As she works to learn English, secure a job and gain financial stability for her family, her children are putting in their own work, whether they know it or not.

Her kids are among a growing number of youth living at domestic violence shelters in the Kansas City area. In fact, for the first time at least in recent years, children now outnumber adults living in KC area shelters — making up 56% of the shelter population.

It’s a sobering reality that’s brought an opportunity for domestic violence shelters to help break the cycle of violence by rethinking how they care for kids. They see an opportunity to stop violence before it starts with the help of their youngest clients. At Newhouse, this is particularly evident in their summer camp, now in its second year, focused on giving youth the tools to heal and build healthy relationships, even after experiencing the trauma of abuse.

“While we serve adults, our significant focus is on the next generation because that’s where we know we really have the opportunity to interrupt and break the cycle of violence,” said Newhouse CEO Courtney Thomas.

More children are living in shelters

The number of children living in domestic violence shelters in the metro has been on the rise for several years.

In 2019, about 43% of domestic violence shelter residents on the Missouri side of the KC metro were children, according to the Missouri Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence. This data encompasses Jackson, Clinton, Platte, Clay, Jackson, Ray, Carroll and Chariton counties.

In 2020, that number rose to 47%, and in 2021, children surpassed adults in shelters, with about 52% of shelter residents being youth. Last year, per the latest available data, 56% of shelter residents were children - about 140 more kids than adults.

Matthew Huffman, with the coalition, doesn’t expect this trend to reverse anytime soon.

He said when a parent with children enters a shelter, data shows they are staying longer too.

The reason for this increase in kids in shelters isn’t exact, but Huffman believes it’s connected to a widespread shortage of safe and affordable housing, as well as limited affordable childcare, particularly in Kansas City. Both are especially challenging to find for parents with multiple children, who may be in more dire need of a shelter space longer-term.

The lasting effects of children’s exposure to violence are well-researched. So often, domestic violence is said to be generational.

“Domestic violence doesn’t just impact individual survivors. It has ripple effects that can impact an entire family, and then we see how it impacts entire communities,” Huffman said.

Girls who witness domestic violence are six times more likely to be sexually abused, according to the US Department of Health & Human Services. Boys who witness domestic violence are ten times more likely to commit abuse as adults.

This statistic is constantly on the mind of Thomas, who joined Newhouse as CEO in early 2020.

It’s in part why, in 2021, leadership at Newhouse transitioned their children’s program — which until then had served mostly as a daycare — into a more intentional and robust program built on evidence-based curriculum and therapy that teaches conflict resolution, self-regulation and coping mechanisms among a host of other skills, all while trying to focus on fun.

“For those that are living in a violent household and that has been all they know, they don’t know that life can be different, and so there is this level of acceptance and level of tolerance that is embedded in their DNA,” she said.

Thomas sees the difference. Now she overhears children, many of whom are developmentally behind their peers, say things like, “soft touches only please,” “I need more space” or “I can do it on my own.”

A different kind of summer camp

Violence can be difficult to talk about, especially with children.

But Courtney Bailey, clinical manager at the Child Witness to Violence Project at Boston Medical Center, said to break the cycle of violence, it’s crucial that kids understand what they witnessed, acknowledge that it was scary, and learn how to navigate their own emotions going forward, like anger and fear.

Thankfully, she said, people and institutions are increasingly talking about how they can best serve kids who are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes.

On a recent Tuesday at Newhouse, help came in the form of mindful yoga. The sound started out as a low hum, then transitioned into more of a wail.

About a dozen kids ranging in age from late elementary school to high school sat on colorful yoga mats as caseworker Esmeralda Campa showed them how to use a singing bowl. She pulled a mallet slowly across the mouth of the bowl as the sound reverberated louder.

“Be gentle with the bowl and be gentle with yourself,” Campa told the children. “The more gentle you are, the louder it is.”

The kids, giggling and restless after a moth interrupted the yoga session, were next instructed to twist, shake and tap different parts of their body. To recognize the power in their limbs. To touch their back, where many people hold anger, to release the tension in their shoulders.

Campa repeated affirmations with them: “I am brave. I am strong. I am loved. I can do hard things. I am capable.”

“Capable of what?” one girl asked.

“Anything,” Campa reassured her.

LaVeeda Simmons, the lead children’s therapist at Newhouse, said the summer camp is about the kids, but ultimately benefits the whole family. On that particular day, Newhouse was the temporary home to five pets, 21 adults and 35 kids.

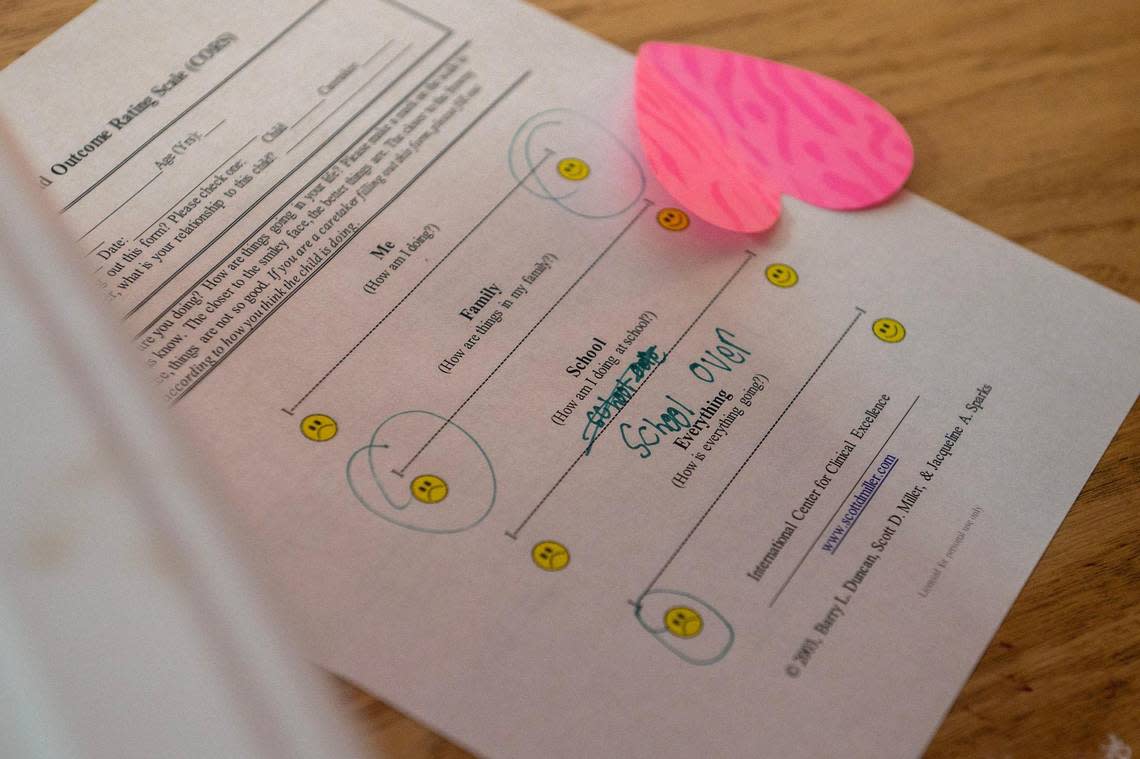

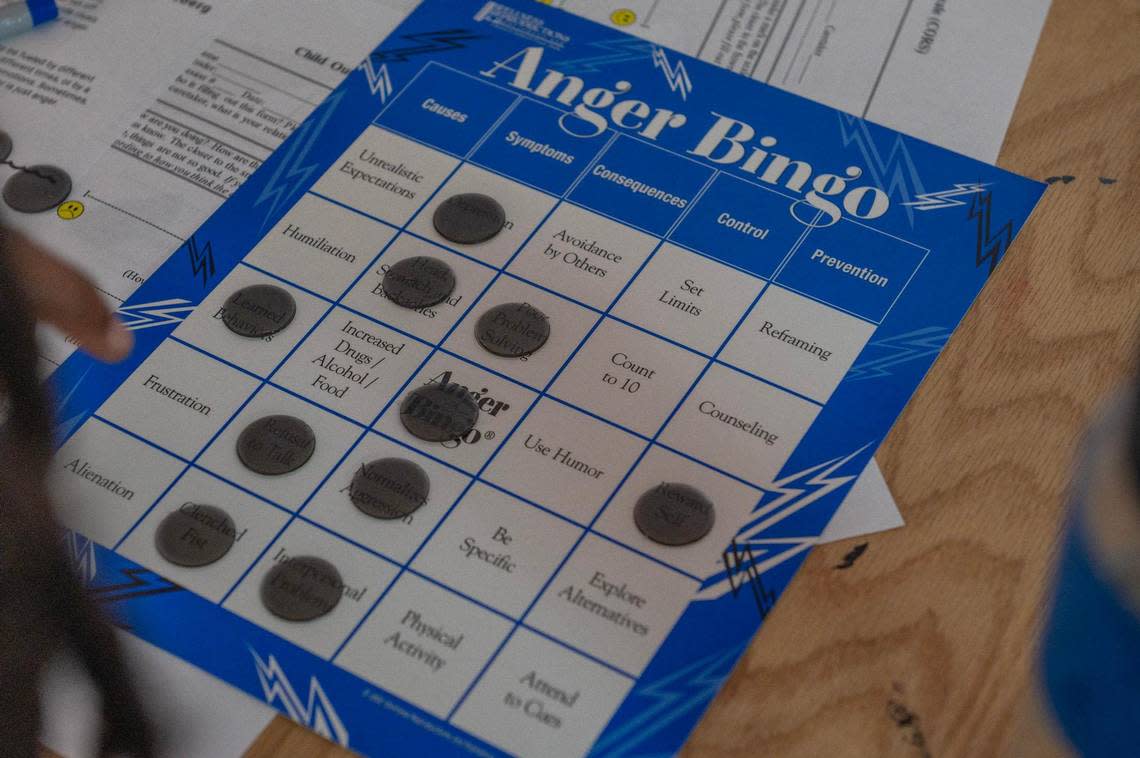

She helps children name their emotions. Then they learn what to do with whatever they’re feeling. This week’s camp was focused on anger management. (The week before was built around healing and nature.)

As Simmons led the kids in a few rounds of “anger BINGO,” she talked with them about safe and unsafe words and actions, going a step beyond just telling the group that it’s not OK to yell or push.

The goal is to give the kids more tools, so that they can set boundaries and communicate when they need time or space.

She said many adults teach children to be quiet. Instead she tells them, “You have a voice. There’s just a time and place to use it.”

Breaking cycles of violence

One domestic violence shelter in Kansas City is taking these lessons outside the shelter walls and into schools.

Project SAFE, a school violence prevention program, brings resources to Kansas City metro schools to help youth heal from violence and build resiliency. In 2022, more than 1,200 students were served across 30 schools through the program, said Lisa Fleming, CEO of the Rose Brooks Center, which runs the program.

Rose Brooks has also seen an increase in the number of kids at their shelter, which Fleming attributes in part to the push to further destigmatize getting help for domestic violence during the pandemic lockdown, when many victims were trapped at home with their abusers.

Pre-COVID, the Rose Brooks domestic violence hotline averaged between 400 and 600 calls a month, Fleming said. The number has grown to about 1,000 calls a month, according to 2022 data.

Between 2019 and 2022, Rose Brooks saw a 22% increase in the number of children staying at their shelter. In that same time, they’ve seen a 16% increase in the ratio of families to single adults served through their housing programs or emergency shelter.

As a result, Fleming said, they’ve working to make the physical shelter environment more accessible for large families, redesigning their therapeutic spaces to be more kid-friendly and building an outdoor space for children. She wants the message to be clear: Children are welcome here.

For parents like Sophia, programs like those at Rose Brooks and the one her children are in at Newhouse are a relief.

“The [kids] are learning how the [emotions] work and how to have the power to control your [emotions],” Sophia said.

They’ve learned the importance of compliments, and words of affirmation. They meditate as a family. At night, it includes foot massages courtesy of mom.

Thomas said it’s also a chance to show the kids that life can be hopeful, positive and fun.

“It brings a great sense of pride to us to be able to show them that life can be different and you can be in control of shaping what happens next,” she said. “None of us can control what has happened to us, but we can be in control of what happens next.”

“You have more power inside of you than you think.”

How to get help

If you or someone you know is the victim of domestic violence, the following resources are available:

Hope House is a nonprofit that operates six domestic violence shelters in the Kansas City area. You can reach it directly at 816-461-4673 or call the metro domestic violence hotline at 816-468-5463 to reach any of its shelters.

The Mattie Rhodes Center provides crisis counseling services primarily in Spanish to Kansas City families. Its services include domestic violence intervention and mental health counseling. You can contact the center at 816-241-3780.

MOCSA (Metropolitan Organization to Counter Sexual Assault) is Kansas City’s largest resource organization for survivors of sexual assault. You can contact the group’s crisis hotline at 816-531-0233 in Missouri or 913-642-0233 in Kansas.

Newhouse is a domestic violence shelter in Kansas City that also provides therapy services, court advocacy and transitional housing. You can call the shelter at 816-471-5800.

Rose Brooks is a domestic violence shelter that also accommodates pets. You can call its 24-hour crisis hotline at 816-861-6100.

Safehome is a domestic violence shelter and nonprofit located in Overland Park. You can call its 24-hour hotline at 913-262-2868.

Synergy Services is a domestic violence and youth crisis resource center based in Parkville. Teens and young adults can call its youth crisis hotline at 816-741-8700 or 888-233-1639 to learn about its services, which include a shelter for runaway and homeless youth.

MOCADSV also has a statewide public directory for those searching for help outside the Kansas City metro.

How you can help

The 10-week-long children’s summer camp at Newhouse is in need of the following items. Those who want to help can email info@newhousekc.org to set up a delivery, or they can order directly from Newhouse’s Amazon wishlist at https://newhousekc.org/donate/.

Individually-packaged snacks

Baby wipes

Children’s underwear

In-kind or monetary donations to help cover costs associated with transportation for activities off-site, including the swimming pool and the zoo.