How KC’s bloody Election Day in 1934 tarnished the city and scarred a 6-year-old girl

One day more than 88 years ago is embedded in the memory of Teresa Peck.

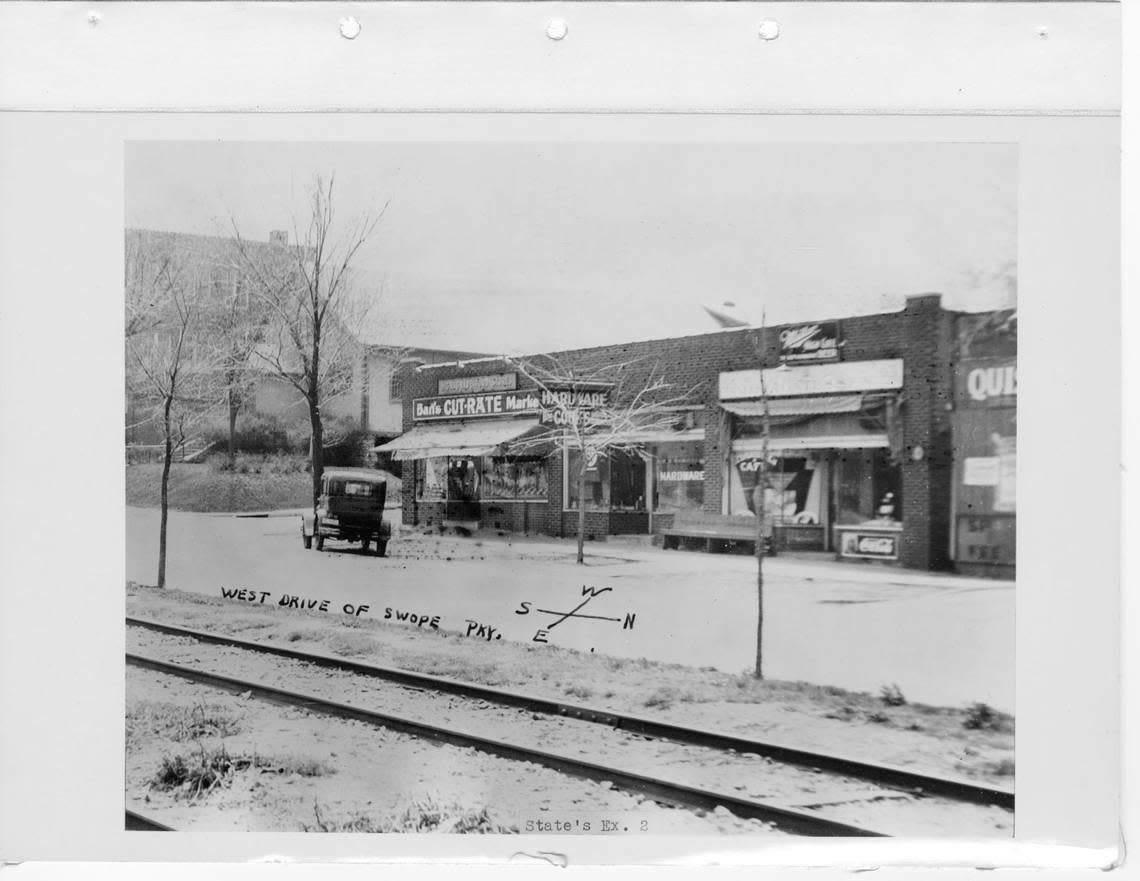

“At age 6, I had just come home from school, and when I opened the door my mother said to get the dog, an English shepherd named Mickey, as she had to get a spool of thread,” Peck said. “We would walk up the hill to the dry goods store situated on Swope Parkway along with other places of business: a deli, a grocery store and a hardware store our next-door neighbor happened to own.”

It was March 27, 1934, and what happened on Swope Parkway that Election Day remains one of the darkest chapters of Kansas City’s history. One expert described it as “probably the bloodiest city election in the history of the country.”

Peck, who was then Teresa Weber, asked about that fateful day in a query to KCQ, The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library that answers readers’ questions about our region. As a writer herself, the 95-year-old Prairie Village resident didn’t compose a garden variety submission:

“Could you inform me of the happenings on Kansas City’s election day March 27, 1934, often referred to as Shootout on Swope Parkway? I only recall that time from my viewpoint as a child who stood at age 6 on the corner of 59th street and Swope Parkway listening to sirens and watching police cars whizzing by in front of us.”

Her query continued from there, and her tale is every bit as compelling as the bloody events of that day.

Violent times

The early 1930s were the heyday of Boss Tom Pendergast’s regime, and Kansas City’s lawlessness made national headlines on a regular basis.

There were two high-profile kidnappings — Nell Donnelly Reed, of Nelly Don clothing fame, in 1931 and Mary McElroy, daughter of city manager Henry F. McElroy, in 1933.

Then came the famous Kansas City Massacre on June 17, 1933, when four law enforcement officers and their prisoner, Frank Nash, were killed in a botched rescue attempt outside Union Station.

A few weeks later, on Aug. 12, 1933, three gangsters were killed in a shootout on city streets that began with the murder of bootlegger Ferris Anthon by fellow mobsters and ended with Sheriff Tom Bash gunning down two of those assassins, Sam Scola and Gus Fascone.

So the climate in Kansas City was already violent.

Meanwhile, the city’s politics were marked by bitter divisions that were far more virulent even than today’s endless rancor. Unlike now, it wasn’t Republican vs. Democrat or conservative vs. liberal in Kansas City, it was Goats (Pendergast’s supporters) vs. Rabbits.

Both sides were Democrats, but they didn’t play well together — not even within their own mammal-named factions.

“We then lived on 59th Street, and it was a short walk up the hill to Swope Parkway,” Peck wrote. “About that time, as I stood waiting on the front porch for my mother to appear, she hollered out to me, ‘I think I will run the sweeper (that is what people called their vacuums) before your father comes home from work.’ So a few minutes later she finished her work and off we went.”

Reformers had been defying the Pendergast machine for years, with little to show for their efforts. But the Citizens-Fusion Party had high hopes for the election of March 27, 1934, when voters would decide on the mayor and nine City Council members.

Still, the path to defeating the machine’s candidates would be filled with obstacles.

In those days, voter fraud was a very real thing. Voting more than once was common — even among the deceased. Then there were the electioneering tactics.

A 1966 article in The Star described “smoking up the precincts” on Election Day: “Gangs of men would ride in high-powered black cars through the wards and precincts and if they thought you were a member of the opposition party or a reformer or they didn’t like the way you looked at them or loitered around the polls, they would dismount from the car, say hello, and then beat you with brass knuckles, fists, baseball bats, gun butts or anything else which was handy.”

The reporter interviewed one opposition party challenger who had worked during the March 27, 1934, election. He said — anonymously, 32 years after the fact — that everyone in the precinct, including the police, took orders from a man named Red.

“Four voters who I knew were Republicans came in,” the man said, “and Red held out four Democratic ballots which were marked already and said, ‘Sorry, friends, but you’ve already voted.’ I thought that was wrong, and I went over to Red and said, ‘Hey, you can’t do that!’ and that’s when Red hit me with brass knucks. See, he busted my nose and blacked my eye.”

Bloody Tuesday

On that March 1934 Election Day, the men in black cars beat dozens of people; 11 were severely injured. They kidnapped others before threatening them and returning them to the polls. William Findley, a Black man trying to defend fellow workers at a polling place, was shot dead for his efforts.

“Upon arriving at the top of the hill and reaching Swope Parkway, we were astonished to find police cars, sirens and fire trucks and all kinds of melee,” Peck wrote. “We never made it to the dry goods store, which was next to the hardware store, thankfully. The owner, our neighbor, had stuck his head out to see what all the commotion was about and was struck in the head by a bullet and died.”

By 6 p.m., the sun was setting but the violence was rising.

Three cars, heading north in the southbound lanes of Swope Parkway — which was divided, with train tracks down the middle — pulled to a stop in front of a delicatessen at 5824 Swope Parkway. It adjoined the polling place in a feed store at 5820 Swope Parkway.

Out burst several men, led by John Gadwood, a Rabbit lieutenant aligned with City Clerk Pete Kelly. The Kelly group was at war with another Rabbit faction linked to L.C. Johnson, director of the Fire Department.

The men confronted Lee Flacy, who had gone to the deli to eat. Flacy was a sheriff’s deputy, but the 35-year-old was still a target for Gadwood’s gang because he supported Johnson. After a brief argument, someone shot Flacy in the stomach. The Gadwood gang fled, but Flacy managed to drag himself outside the deli and began firing at the gangsters.

The resulting shootout left Flacy, who had married less than three weeks earlier, dead. Larry Cappo, a former boxer who was with Gadwood, was clinging to life in the rear of an overturned getaway car, its wheels still spinning. P.W. Oldham, the 78-year-old owner of the hardware store adjoining the deli, was lying on the sidewalk bleeding from a bullet wound in his forehead.

Oldham and Cappo were taken to General Hospital, where they occupied adjoining beds surrounded by family members.

The March 38, 1934, edition of The Star quoted Oldham’s niece, Mrs. Fred C. Hinds:

“All night they breathed there together, waging war with death. Mrs. Cappo, the mother of the gangster, was there. We couldn’t blame her. We were sorry for her. So we prayed together, for the slayer as well as the slain.

“The gangster went first, about an hour before my uncle died.”

“My mother said later if she hadn’t run the sweeper, we would have been at that exact spot and probably would have been killed,” Peck said. “I was so sad later about our neighbor, as he used to sit on his front porch swing and wave to me as I came home from school. So at age 6, I knew what it was like to know grief.”

Aftermath

An article in Time magazine on April 9, 1934, detailed Kansas City’s dark day, saying, “When blackjacks were pocketed and votes were counted, Kansas Citizens knew the worst: The Fusion attempt to break the rule of Boss Thomas Joseph (‘Big Tom’) Pendergast’s Democratic machine had failed.”

Although reformers claimed two seats, the machine kept control of the council and returned Bryce B. Smith to the mayor’s office. Within a week, Smith fired director of police Eugene Reppert, and nine police officers were discharged.

Gadwood went on trial in mid-July for the murder of Flacy. He was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years. He served only three. No one was ever charged in the shooting deaths of Oldham or Findley.

And the violence continued.

▪ On July 10, 1934, Kansas City crime boss Johnny Lazia, a Pendergast man, was gunned down while exiting his car in front of his Armour Boulevard home.

▪ On March 1, 1935, gangster Joe Lusco (who had been Cappo’s boss) was shot outside his home by an assailant in a car and was permanently disabled. He died 10 years later.

▪ On Aug. 18, 1935, Michael (Jimmy Needles) LaCapra, who as a government witness had implicated Lazia in the Union Station massacre, was found dead in upstate New York with two bullets in the back of his head.

If you’re thinking, “Somebody should make a movie about this,” you’re too late. Famed director Robert Altman, a Kansas City native, did just that. Sort of. His “Kansas City” was set around an election in March 1934 and included kidnappings and a voting-place shooting.

Filmed here in 1995, it was released in 1996 to mixed reviews. Perhaps it would have been more compelling if he had incorporated the firsthand experiences of a 6-year-old girl.

“When Robert Altman was in the process of making the movie ‘Kansas City,’ he had a mention in The Star if anyone had a memory of the year 1934 would they get in touch,” Peck said. “I did get in touch. I got a call from Hollywood asking more info. I mailed him the entire article, and about a month later I got a call saying did I know that Robert Altman was going to use what I wrote? I actually didn’t know, but I had read that when Altman found something of interest, he often used it but in his own way.

“In the movie, he had the happening to be at night rather than in the daytime and changed some other things, but he got the idea from me. It ended up that I was an extra in his movie but had some special advantages like having my own trailer and Italian hairdresser etc.”

That 6-year-old girl, by the way, has remained in the Kansas City area virtually her entire life. In fact, she married Don Peck in the St. Louis Catholic Church down the block from the 1934 shootout on Swope Parkway. They will celebrate their 50th anniversary on Nov. 29.