Kansas City police don’t use best practices in missing persons cases, advocates say

Nearly every day of the week, listeners of KPRS-FM radio in Kansas City hear the voice of Damon Daniel making a plea for a missing teen to return home.

As president of the AdHoc Group Against Crime, Daniel has long used the urban music station as a portal to reach a larger audience. It is a relationship that goes back nearly 45 years, to when then-AdHoc president Alvin Brooks used the radio station to tell listeners about the unsolved murders of nine Black women.

It’s partly because of the group’s decade-long crime fighting and community outreach efforts that relatives of missing people often go directly to AdHoc for help. But it’s also because some families find working with the police department difficult and frustrating, Daniel said.

“When family members or friends go missing, there’s always some obstacles in terms of assistance and there’s not a lot of public information to educate the public on the processes,” Daniel said.

The Kansas City Police Department’s handling of missing persons cases has long been a source of frustration for families, social activists and neighborhood leaders who say police are often not responsive to their concerns, especially when it comes to missing Black women.

That frustration boiled over last month when a 22-year-old Black woman escaped from the Excelsior Springs house of a man who she said kept her captive for weeks. The incident came just weeks after police had dismissed as rumors a report in the community that a serial killer was targeting Black women.

Black community leaders reacted with anger to reports that the victim told neighbors the man had harmed others and killed two people.

Some questioned how thoroughly those claims were being investigated, and whether local law enforcement agencies are contributing to an environment where general community concerns are going unheard or unreported.

Among the gaps pointed to by advocates: The police department does not maintain a list of active missing person cases that is accessible to the public. It does not require the missing persons unit to file monthly reports tracking which cases are being closed or going unsolved, and it does not track the demographics of missing persons.

As a result, those who provide support to families of the missing say it’s nearly impossible to know what resources police are using to search for specific missing persons, or whether Black and brown communities are being disproportionately affected.

In Kansas City, it is left to detectives to decide whether individual cases are worth pursuing, based on whether that person is in immediate danger or might harm themselves, police say.

Many advocates who study the best practices in the field say every department should have strategies for alerting community members of missing persons and communicating with them during a search.

A national clearinghouse for missing person cases provides a place for the public to look up missing persons in their area, but advocates say police don’t use it as often as they should.

Interim Police Chief Joseph Mabin said the department investigates every missing person report it receives, regardless of race, sex, or where they live. The KCPD uses its own social media platforms to distribute information and frequently sends the news media email alerts of missing persons.

“And as always, we continue to respond to people in need, no matter the location,” Mabin said recently. “We’re not doing this because of social media rumors. We’re doing this because we hear you and the members of our community deserve to be heard and have their fears addressed in the proper forum.”

Mayor Quinton Lucas, who is a member of the police board, said the department needs to do a better job communicating with the public and addressing concerns regarding reports of missing Black women.

“And it can’t just always be in press releases,” said Lucas. “What you gotta do is put your face out there and build that presence of trust. Not just always say trust us, because the reality of it is, some people just won’t.

“We should take these opportunities as a learning opportunity,” he said.

How KCPD investigates missing persons cases

Darron Edwards, lead pastor of United Believers Community Church, is among the Kansas City faith leaders and community activists who have urged more transparency and accountability from the police department.

He said he finds it troubling that the police department doesn’t track missing persons statistics.

“It’s not enough to just know about something,” he said. “You have to do something about it. That’s the responsibility all of us have.”

The KCPD does not produce monthly statistics on missing persons as it does for homicides, nonfatal shootings, robberies and other crimes.

It is possible to gather that information, but it would require pulling each missing person report and compiling that data, which is more labor intensive, Capt. Leslie Foreman, a police spokeswoman, said in an email.

The vast majority of people who are reported missing are found very quickly, often within just a few days, Foreman said.

“So we could provide the number of missing person reports taken in a certain time frame fairly quickly, but to look at specifics beyond that we would need to go into each report to get more detailed data.”

The KCPD has two sergeants and seven detectives assigned to investigate adult missing persons. Two sergeants and eight detectives investigate missing juveniles.

Overland Park police have 20 detectives assigned to a Crimes Against Persons Unit that handles missing persons, but they also investigate other crimes, said Officer John Lacy, a police spokesman.

The Kansas City, Kansas Police Department has one detective in its Investigations Bureau assigned to missing persons and runaways. However, he has the ability to tap other detectives to assist as needed, said Nancy Chartrand, a police spokeswoman.

Chartrand was able to offer some specifics about the KCK police department’s missing persons cases. As of Wednesday, she said, the department had 16 open missing person cases that included one Black female, three Hispanic women and two white females. The rest were seven white men and three Black men.

In Missouri, there is no statewide standard or protocol for investigating missing persons cases.

One of the best resources for information is maintained by the Missouri State Highway Patrol, which keeps a list on its website that is frequently updated. As of Thursday, the highway patrol reported 240 missing persons in Jackson County. Of those, 39 were Black women. Those numbers were compiled from data collected by the National Crime Information Center or NCIC, which is a federal law enforcement database.

The KCPD’s missing person cases are also documented in the NCIC database. But information about who has been reported missing and where they have disappeared is often not available to the public, which advocates say needs to change.

If police receive information that someone is in imminent danger to themselves or others, the department will immediately begin to search for the victim, said Officer Donna Drake, a police spokeswoman.

That investigation includes review the missing person’s social media. Detectives will knock on doors, where the victim lived or was last seen. They can also activate the helicopter unit or K9 unit to aid in the search efforts.

The missing persons unit does not file a monthly or weekly report regarding its cases and the resources it has used.

“We always encourage citizens to make a report if they are concerned about someone they believe is missing,” Drake said. “Often people will call in and simply ask us to conduct a welfare check on someone, as long as there is a physical address or location we can send the officers.”

“The vast majority of reported missing persons are found or return on their own,” Drake said.

NamUs

Maureen Reintjes, a spokeswoman for the nonprofit Missouri Missing, creates missing posters and guides families through the process of reporting a person’s disappearance.

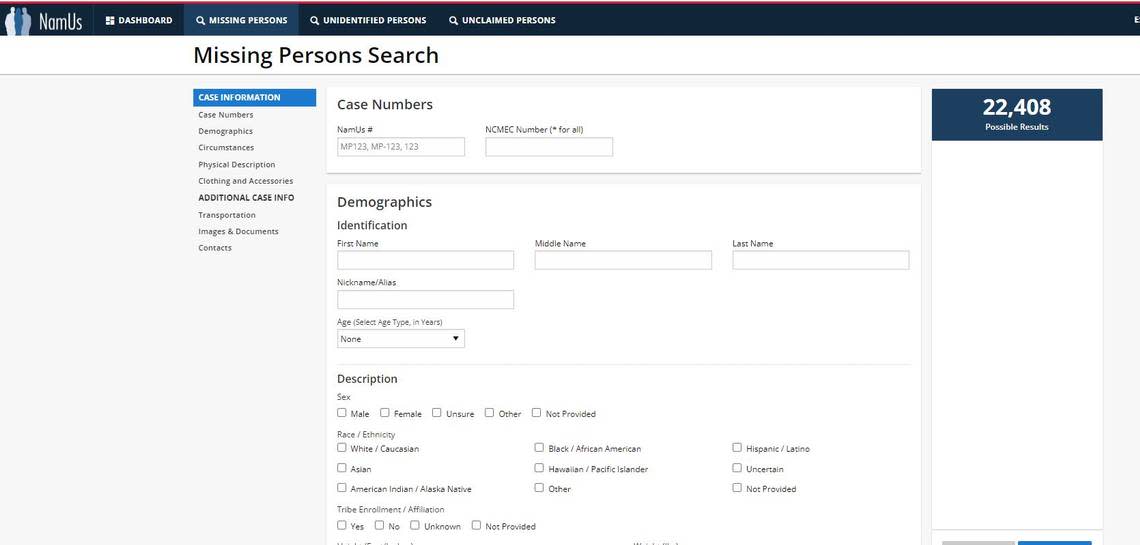

When Reintjes meets a new family, she always asks if the police have submitted the missing persons report to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs.

The national system allows the public to search for a person who’s been reported missing by area, age, gender, race, name or even distinctive physical attributes. Administrators working at the database also work one-on-one with families to keep the person’s file updated by gathering dental records and other descriptive information.

“We’ve had families in the Kansas City area whose loved one had been missing for decades and they typed a description of the person’s tattoo and found them several states away,” Reintjes said.

“I’m usually the first person to tell them about these services,” she said. “Really it should be the police who are letting them know what they could do to spread the word.”

Foreman, a KCPD spokeswoman, said police agencies are often advised to enter information into NamUs after a missing person has been gone for six months.

“We do utilize it, but oftentimes people are located fairly quickly so they are not entered in,” she said.

A bill in the Missouri House of Representatives filed by Republican Adam Schnelting of St. Charles County, aims to require police to report their missing to NamUS.

Similar legislation has already been enacted in 13 states from Oklahoma to New York.

Common problems in law enforcement

A public clearinghouse for information about missing person is an important tool, said Derrica Wilson, the co-founder of the Black and Missing Foundation, based in Maryland.

For her organization, NamUs is one of the few places where they can examine how many people of color are going missing,

The FBI publishes an annual report on the number of people who are reported missing but the racial categories are limited to Black, white and Asian.

“Sadly the numbers just don’t add up,” Wilson said of the federal data. “There’s so many Hispanic and Indigenous people being lumped in as White or going uncounted.

“We have had situations where community members have gone to law enforcement and [they] simply did not take a police report,” she said. “There’s this perception that with law enforcement our lives just don’t matter,” she said of Black, Indigenous and other communities of color.

Wilson is among those advocates who say police should have an internal auditing process to see what missing persons cases remain unsolved.

Christopher Boyer, executive director of the educational nonprofit, National Association For Search And Rescue, which prepares curriculum and standard practices for people involved in missing person searches, said it’s difficult for police to track the missing.

Boyer said that when a person is reported missing, a smaller law enforcement agency will do what they can, but often it’s only a matter of time before they run out of resources and stop looking.

He recommends that each department have strategies to lean on their community for searches.

‘We will do it with them’

Daniel spoke at an event Saturday where he and other panelists discussed violence against Black women. They expressed their concerns about how police handle missing persons cases.

The event was held at the Lucile H. Bluford Branch of the Kansas City Public Library and was hosted by the nonprofit Shirley’s Kitchen Cabinet and KPRS-FM.

When AdHoc works with families of missing people, they insist that a police report be filed to ensure that law enforcement can do its part and to verify the person is missing.

From there, the group will produce fliers with a photo of the missing person and use social media to get the word out.

Volunteers are occasionally summoned to join the family in canvassing neighborhoods where the missing person was last seen or had frequently visited.

“Our labor and the intensity that we put into a missing persons case, relies heavily on the family,” he said. “So if the family is motivated to canvas and if the family is motivated to do those kinds of things, then we will do it with them.”

Hitting the radio airwaves has been key function of their search efforts.

Myron Fears, operations manager and program director for the Carter Broadcast Group, which owns and operates KPRS-FM, said it has been the station’s mission to advocate on behalf of the city’s Black and urban community. Working hand-in-hand with AdHoc serves that purpose.

“We are embedded in this marketplace and we look at our radio station as an institution just like we will look at a school, or a church or a major organization that serves the community,” Fears said. “And our primary goal is to serve as the voice of the African-American community but also serve the community at large.”

On several occasions, Daniel said he has the parent with him on the radio to help urge a missing teen to return home.

“We have to put ourselves in the shoes of those families who have loved ones missing. Because you feel helpless,” he said.