Kansas City’s Fairyland Park conjures fond memories — and the shadow of racism

No, the roller coaster at Fairyland Park never jumped the rails and landed in the park’s giant swimming pool. And that passenger who supposedly flew out of the coaster and splashed down below? Never happened.

But it’s possible that a man lost his glass eye in the pool, and it’s totally factual that a priest was seriously wounded by another priest at a Fairyland shooting gallery. Accidentally, of course.

Such is the legacy of Fairyland Park, perhaps Kansas City’s biggest memory-maker of the mid-20th century. Ninety-nine years after the amusement park opened and 45 years after it closed, it still conjures up an array of recollections — some true, some not.

Just how firmly Fairyland was planted in the texture of the city is clear from the queries — at least four in the past year — submitted to KCQ, The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library that answers readers’ questions about our region. All wonder, in one way or another, what happened to the place.

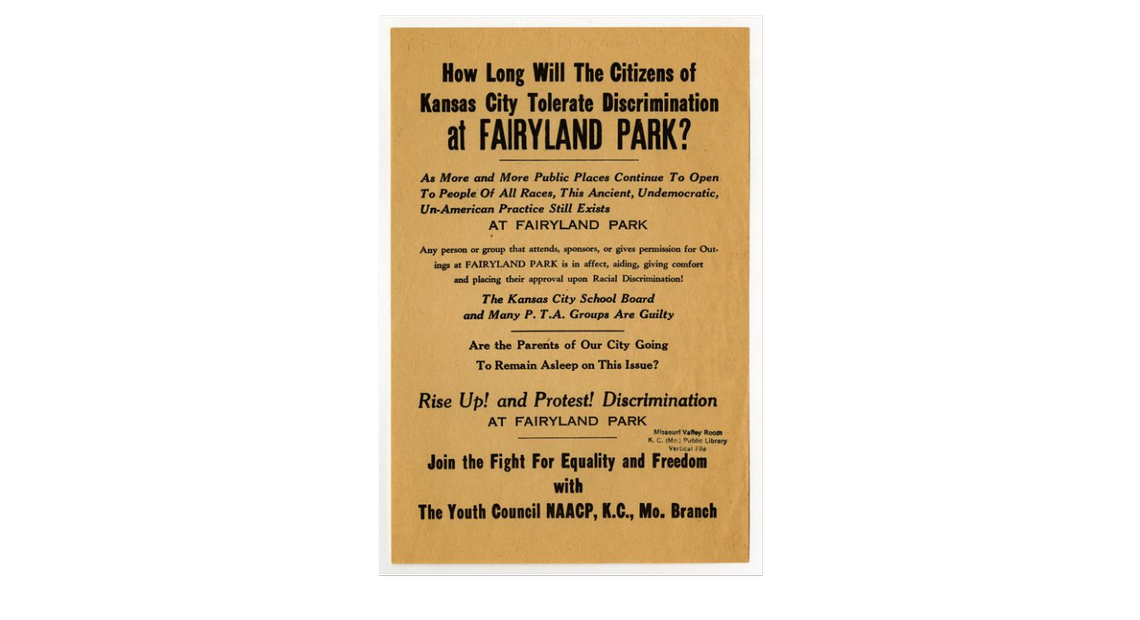

Most succinct was a submission from Catina Taylor of Kansas City, who asked: “What amusement park existed in south Kansas City that you could visit via the streetcar and practiced discrimination?”

The exclusion of Black people cast a shadow on most of Fairyland’s history, even if white kids growing up from the 1920s to the ’60s likely were blissfully ignorant of the park’s discrimination. Some are now senior citizens with a lot of memories — enough to fill a book.

Jody Valet has done just that.

Valet, whose great-great-grandfather, Salvatore (Sam) Brancato, opened Fairyland, expects her book on the park to come out next year in time for its 100th anniversary. She said the history will include the good, such as the many romances ignited at Fairyland, as well as the bad, such as the discrimination practiced there. It will also have a dose of the macabre.

“There were so many weird things that happened in the park that people don’t even know about,” Valet said. “There was a stabbing. Some guy killed his girlfriend in the parking lot, and then before he could kill himself, they caught him. There was a kidnapping. There were a couple of kidnappings actually. Robberies. All kinds of crazy stuff.”

Michelle Tyrene Johnson provides a different take on Fairyland’s history.

The fourth-generation Kansas City, Kansan, wrote the play “Only One Day a Year,” a fictional account of a young girl’s experience with Fairyland’s very real policy that at one time permitted Black people admission to the park only on one specific day each year. The play is scheduled to run Jan. 31-March 5 at The Coterie.

Johnson never went to Fairyland, even though it had been integrated when she was a child.

“I didn’t go, and that’s why it’s always been at the back of my mind,” she said. “Because my mother wouldn’t take me. My mother’s thing was, ‘If I couldn’t go as a kid, I’m certainly not taking my kid there.’”

First, the history

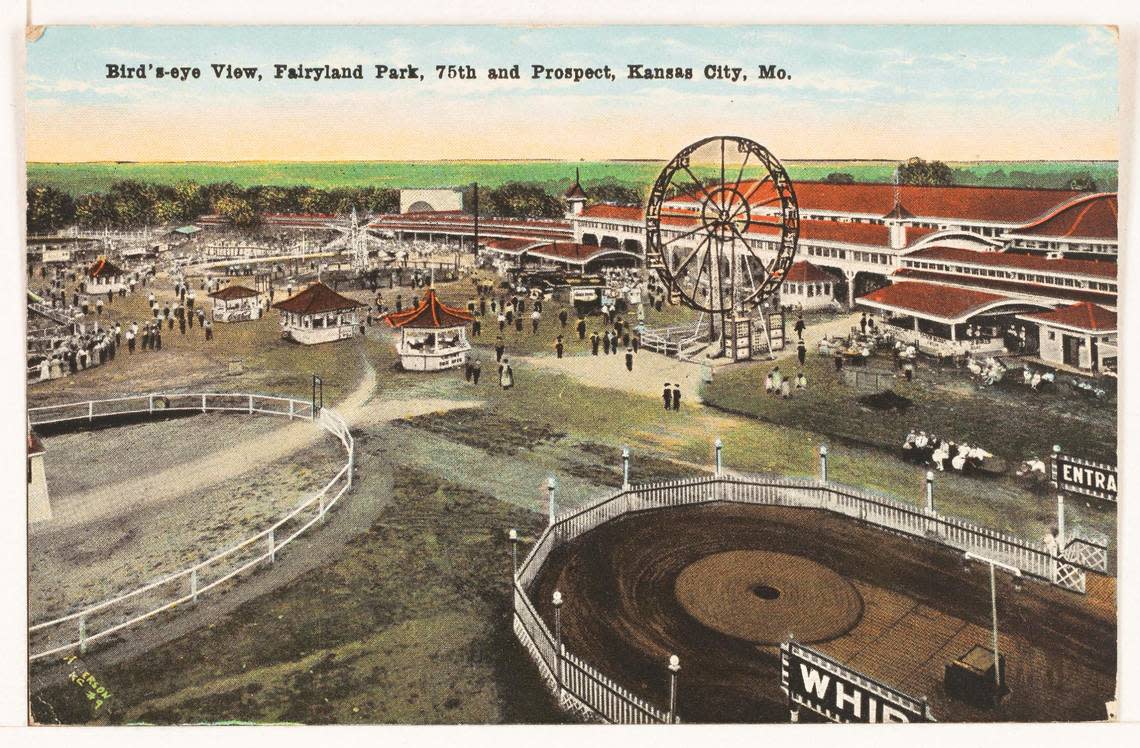

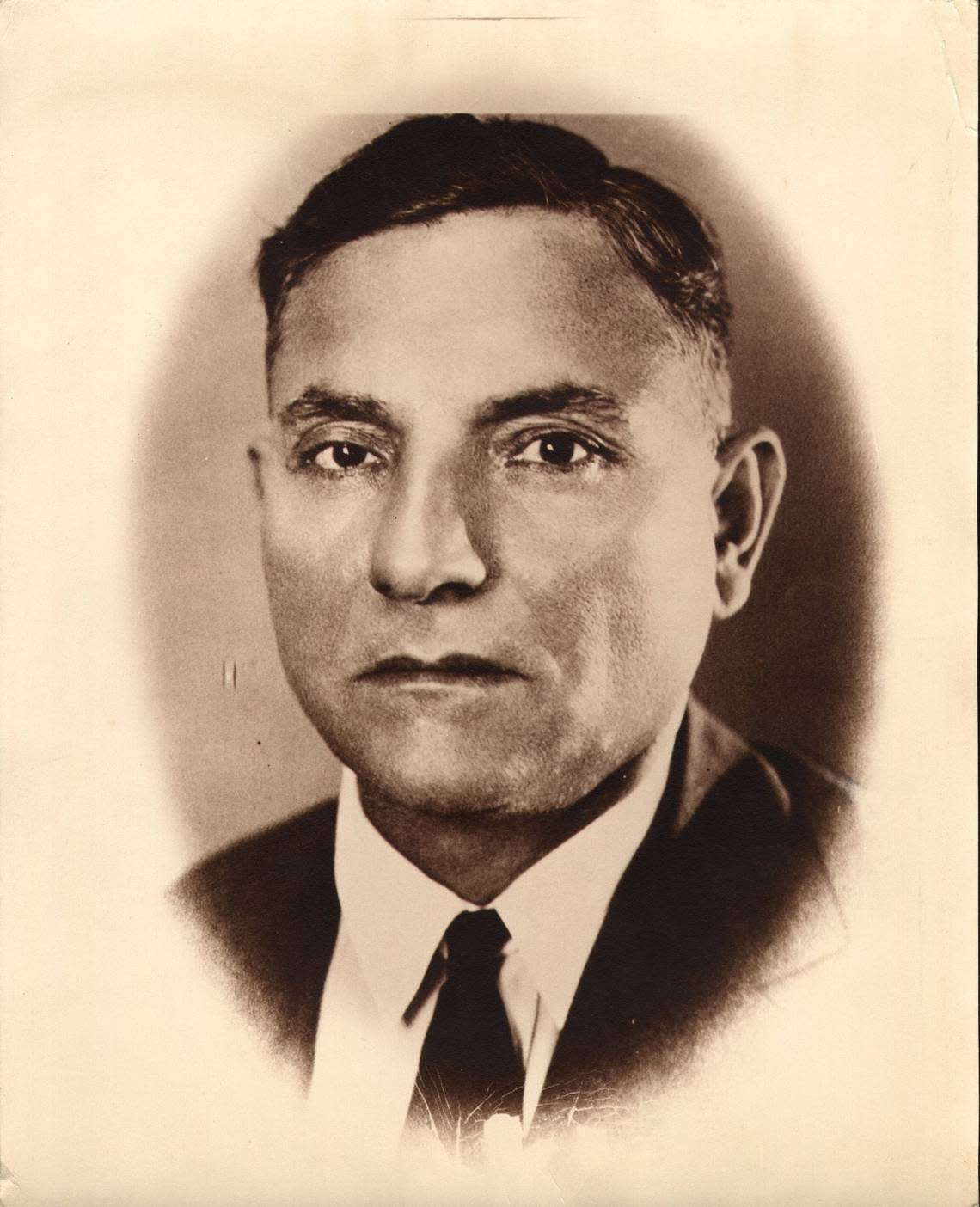

Brancato, a blacksmith from Sicily who immigrated to the Kansas City in 1896, opened Fairyland Park on June 16, 1923. It covered 80 acres at the southern terminus of the Prospect Avenue streetcar line at 75th Street.

Billed in advertisements at “Kansas City’s Million Dollar Playground,” it entered into competition with the existing Electric Park, Fairmount Park and Winnwood Beach and would outlast them all. Admission was 10 cents.

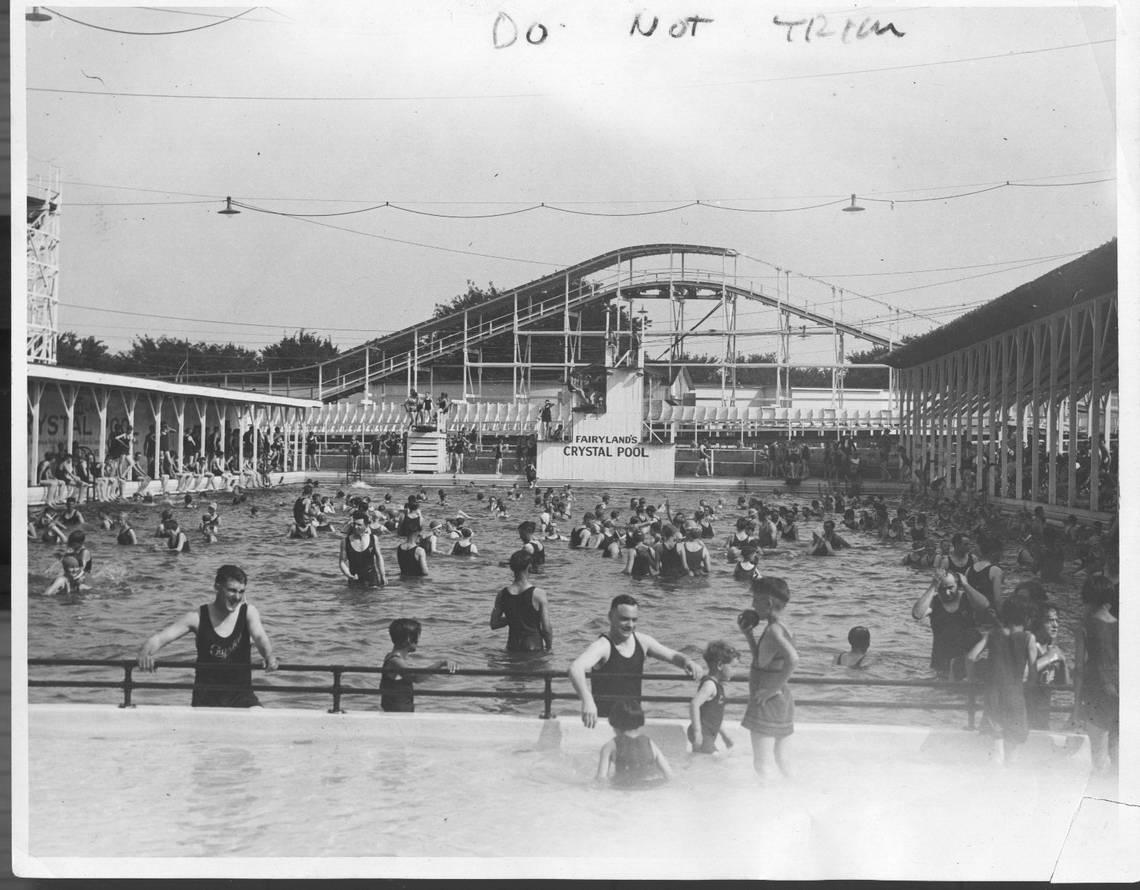

Along with a roller coaster, Ferris wheel and other rides, Fairyland offered carnival acts and games, a fun house, a massive pool and an outdoor pavilion that showcased the nation’s top musical acts, many featuring Black performers. The concert/dance hall was destroyed by a fire, one of at least five at Fairyland, in 1943.

New rides and attractions were added throughout the years, including the Fairyland Twin Drive-In theaters in 1961 and the world-class Wildcat roller coaster in 1967.

Fairyland’s ownership remained in the Brancato family until its 1977 shuttering, blamed on a damaging windstorm and competition from the new Worlds of Fun. The land where the park stood now is bisected by Bruce R. Watkins Drive and, after much of it stood empty for two decades, holds Satchel Paige Elementary School, the Alphapointe Association for the Blind, the Metro Patrol police station and the Paige Pointe affordable-housing townhome complex.

One big part of Fairyland lives on. The Wildcat roller coaster, which sat abandoned for more than a decade, was dismantled and moved to Six Flags Frontier City in Oklahoma City. It debuted there in 1991 and still operates today.

Days of discrimination

Fairyland Park was hardly the only place that practiced segregation in Kansas City, where hospitals, schools, public parks, swimming pools, golf courses, restaurants, nightclubs, department stores, hotels, theaters, bowling alleys and art galleries also did so.

Segregation was almost as pervasive here as in the Deep South, although you wouldn’t know it from the history books taught in local schools.

“We’ve all grown up seeing the signs that say, ‘No coloreds,’ right?” Johnson said. “But when it comes to Kansas City discrimination, it’s one of those things where everybody knows it, but it’s not like they put up a big sign.”

Fairyland’s policy included exceptions. Black people were allowed to enter for private events such as company picnics, usually held after the park had closed for the season. Similarly, an advertisement in the Black-owned Kansas City Call indicates the park opened to Black people for six days in early September 1932.

Also, according to the 2008 book “Up Close: Ella Fitzgerald” by Tanya Lee Stone, Fitzgerald and the Chick Webb Orchestra played back-to-back nights at Fairyland, one for white audiences and one for Black people.

“I grew up hearing stories about all these Black musicians that were friends of my family,” said Valet, who was raised in Pleasant Hill. “I knew they were friends of the family … but they couldn’t ride on the rides.”

She wasn’t aware of Fairyland’s segregation policies until she was in her 20s, well after the park had shut down. “And I was so upset, I was in tears.

“Segregation was wrong. What happened at Fairyland and all these places in Kansas City, it was wrong.”

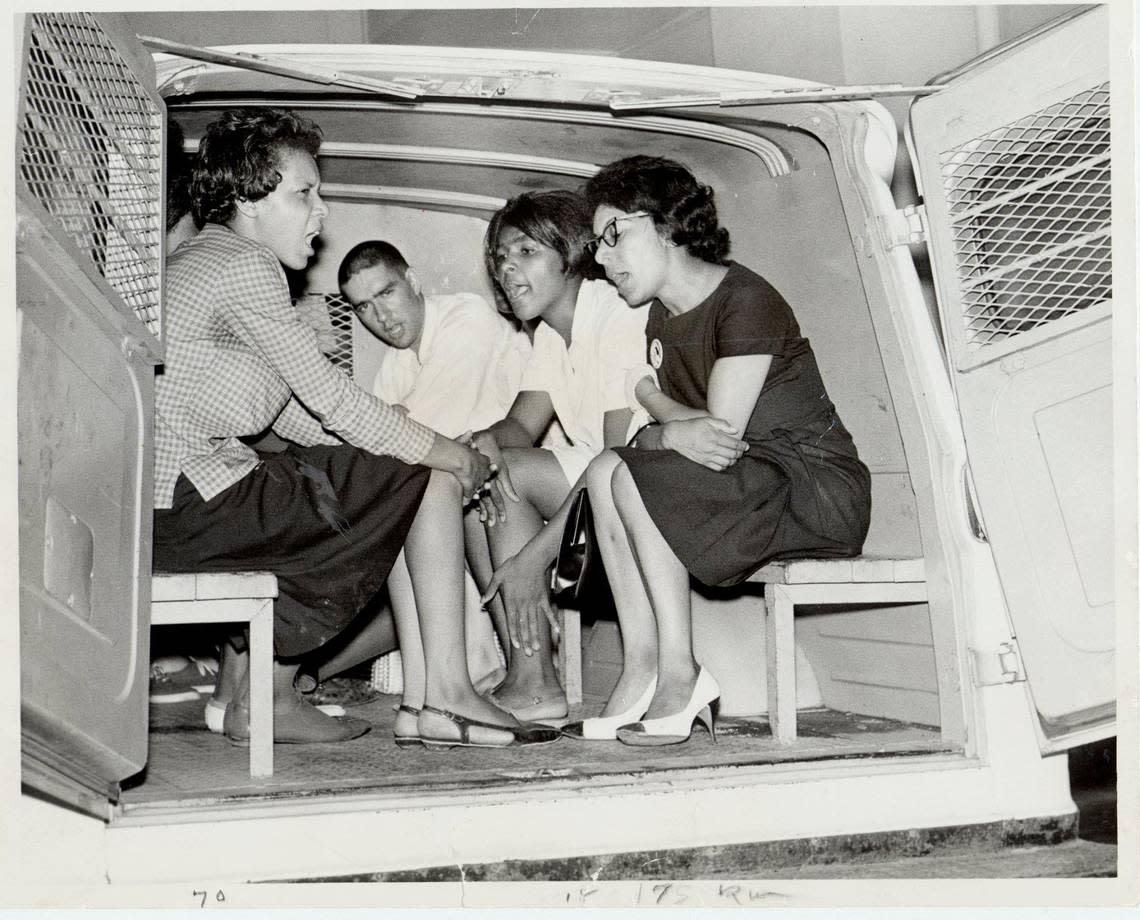

Fairyland’s segregation received the most publicity largely because of high-profile protests in the early 1960s. Thirty-four people were arrested on May 13, 1961, after blocking the park’s entrances. More arrests, as well as lawsuits on both sides, followed over the next three years.

In April 1964, Kansas City voters approved a public accommodations referendum desegregating public facilities, and in July 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act.

Earlier that year, Fairyland owner Mario Brancato had announced that the park would permit Black customers when it opened for the summer season and that he was dropping six lawsuits against demonstrators. However, the swimming pool was allowed to continue to exclude Black people because a newly formed group, the Southeast Swim Club, leased the pool and operated it as a membership organization. It closed permanently within a few years.

Johnson, who in addition to being a prolific playwright is a lawyer and a public radio producer, has no desire to devalue the recollections of the Fairyland generation.

“I’m not trying to take away your memories,” she said. “I’m just saying that there was another side to what you didn’t see.”

True or false

Maria Brancato Accurso, a granddaughter of founder Sam Brancato, is helping her cousin Jody Valet separate fact from fiction for her book.

“A lot of things that people did say weren’t true,” she said.

She should know. Accurso not only worked at Fairyland Park for years, she also lived there from 1959 to 1966, sharing a house that was connected to the park office with her mother and father, Mario Brancato, who had taken over ownership after Sam’s death.

Using the expertise of Accurso and her cousin, along with The Star’s archives, we can put to rest or confirm stories that have circulated — especially on Facebook — about Fairyland.

▪ The park was run by the mafia. False. “I know a lot about mobsters because I’ve researched mobsters,” Valet said. “They don’t work that hard, people.”

She also points to evidence that her great-great-grandfather was victimized by the notorious Black Hand but refused to pay the notorious group’s extortion demands.

▪ People were trampled during a panic at the fun house. False.

▪ Count Basie, Glenn Miller, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra, Charlie Parker, Ella Fitzgerald and Dizzy Gillespie were among the musicians who performed there. All true except Sinatra.

The jazz greats played at Fairyland before Accurso’s time, but she and Valet have heard numerous family stories about them. Accurso shared a tale of her own from an encounter with Basie, once a Kansas City jazz man, many years later in Las Vegas.

“He was there gambling, and, I don’t know how I got the nerve, I went up to him and said, ‘Mr. Basie,’ and he was very nice, very friendly, and I said, ‘Did you ever play at Fairyland Park?’ And he said, this is true, he said, ‘Yes, I did. You’re a Brancato, aren’t you?’ That’s a true story. I couldn’t get over it.”

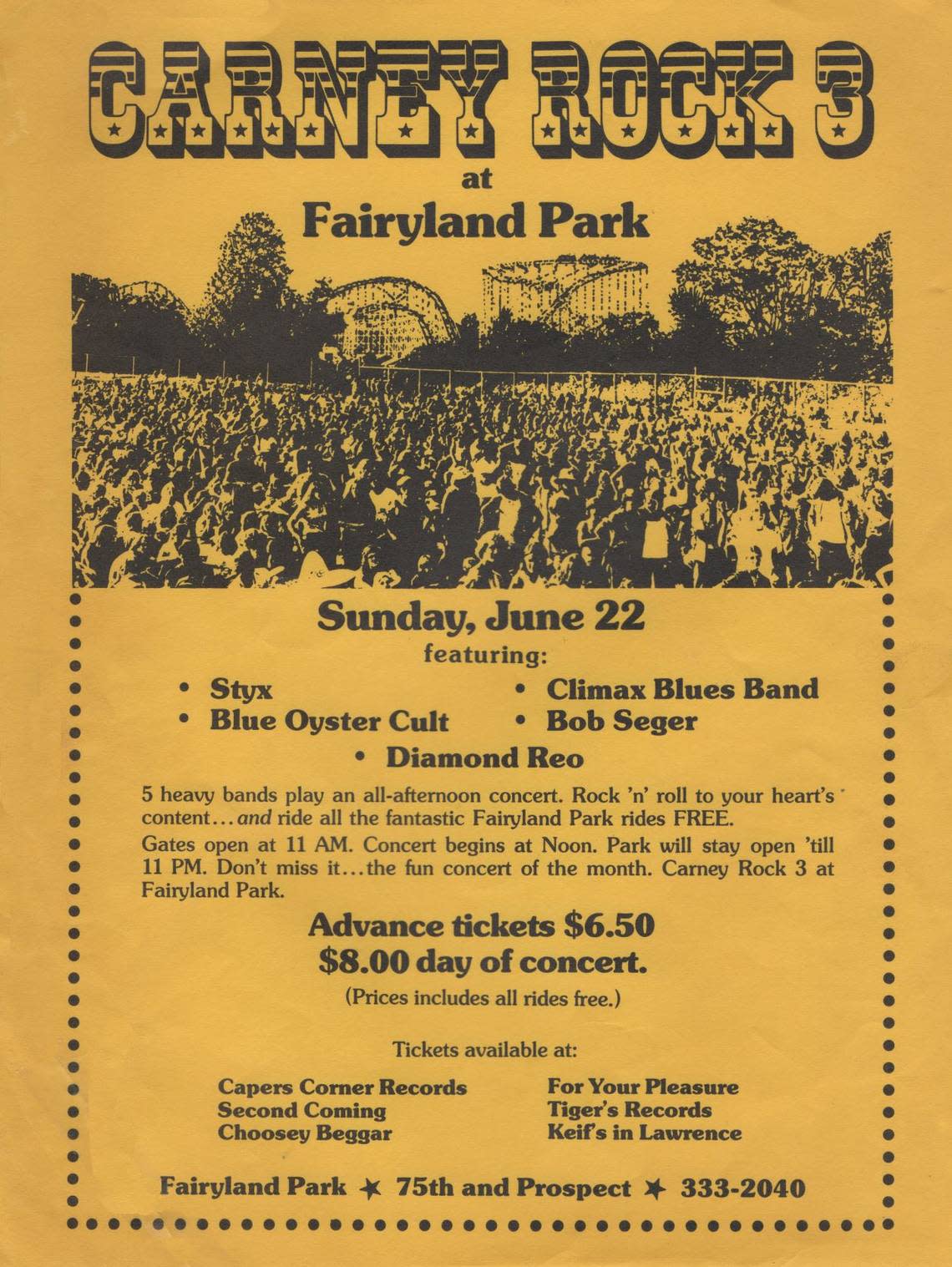

▪ Big-time rock bands played there in 1970s. True. Billed as Carney Rock, two concerts were held in 1973 (REO Speedwagon, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Quicksilver Messenger Service and others) and one in 1975 (Styx, Bob Seger and others).

▪ Riders were fatally injured on the roller coaster. False. A 21-year-old man did fall from the ride on July 4, 1966, after sneaking under the safety bar to get out of his seat. He was hospitalized but recovered.

▪ Johnny Weissmuller, Olympic swimming champion and future movie Tarzan, swam there. True. He put on an exhibition in June 1931.

▪ A woman not only drowned in the Fairyland pool, she had turned blue by the time ambulance attendants pulled her out of the water. False. But a woman astride a horse leaped into a pool of water as part of a carnival act.

▪ Revisiting that man who supposedly lost his glass eye in the pool. Neither The Star nor Valet has any record of it, but she doesn’t rule out the possibility. “It’s a maybe,” she said.

▪ The kidnappings Valet mentioned, on the other hand, are well documented. In 1926, five bandits grabbed park manager Sam Benjamin at his home, drove him to the park office and forced him to open the vault. In 1960, a man snatched a 5-year-old boy at Fairyland. After a search spanning two days, the boy was found unharmed in Joplin.

▪ Finally, there was the priest-on-priest gunplay.

On Aug. 2, 1939, Catholic priests George W. King and John J. Murphy visited the park’s shooting gallery at about 11:05 p.m. There are conflicting reports about the details, but Murphy’s gun discharged, and a bullet struck King in the back.

Shooting galleries used real guns with “soft” bullets in those days, so the injuries were severe, including internal bleeding. King spent more than a year recuperating and walked with two canes for the rest of his life.

Jody Valet welcomes stories and photos from former Fairyland patrons and employees for possible inclusion in her book. They can be submitted at fairylandparkkc@gmail.com.