‘They just don’t care’: Trains blocking roads can be deadly. It’s only getting worse

You never knew when or how long a train might block the Maple Street crossing, the only way in or out of the neighborhood where Gene and Linda Byrd lived on the edge of town.

“You couldn’t go to the store to get a gallon of milk for dinner, because you didn’t know when you would come back,” Linda said. “I mean, it could be 30 minutes, it could be two hours.”

More troubling, their son Chad said in a 2015 TV news interview: What if a train was parked at that crossing and prevented an ambulance from helping someone who was gravely ill on the other side?

Five years later, that’s what happened when 66-year-old Gene Byrd got out of bed with chest pains and collapsed around 1 a.m. on Sept. 6, 2020. The EMTs who responded to the 911 call were blocked by an idling BNSF freight train, and when a cop pleaded with the conductor to move the rig, he refused.

Several minutes passed before the train finally moved and the ambulance arrived at the Byrds’ house, Linda said recently, fighting back tears as she recalled the night she lost her husband of 48 years.

“They put him on the board,” she said. “I don’t know if he was breathing at that point.”

Medical treatment has come too late for countless others when parked or plodding trains blocked ambulance crews from getting people the help they needed in time, The Star found in a months-long investigation. Delayed at blocked crossings, fire trucks have arrived too late to save people’s houses from burning to the ground.

Much of the blame rests on congressional inaction and a series of court rulings over the past 20 years that have stripped from state and local officials the authority they once had to limit how long trains could block crossings. Only Congress can restrict a train’s movement, the courts have ruled in state after state.

Yet Congress has failed repeatedly to pass laws giving regulators the authority they’d need to address a problem that has only grown worse due to operational changes within the railroad industry.

“We don’t have explicit authority to prohibit a train from occupying a crossing for any length of time,” said Karl Alexy, chief safety officer for the Federal Railroad Administration.

The U.S. Supreme Court so far also has refused to weigh in. Ohio is now waiting to learn whether the high court will hear the appeal it filed last month of a state supreme court ruling that nullified Ohio’s blocked crossings law.

That railroad companies can block crossings indefinitely is one of the more egregious examples of the wide latitude railroads have been given to operate as they see fit, dating all the way back to when the first tracks were laid in the U.S. in the early 1800s.

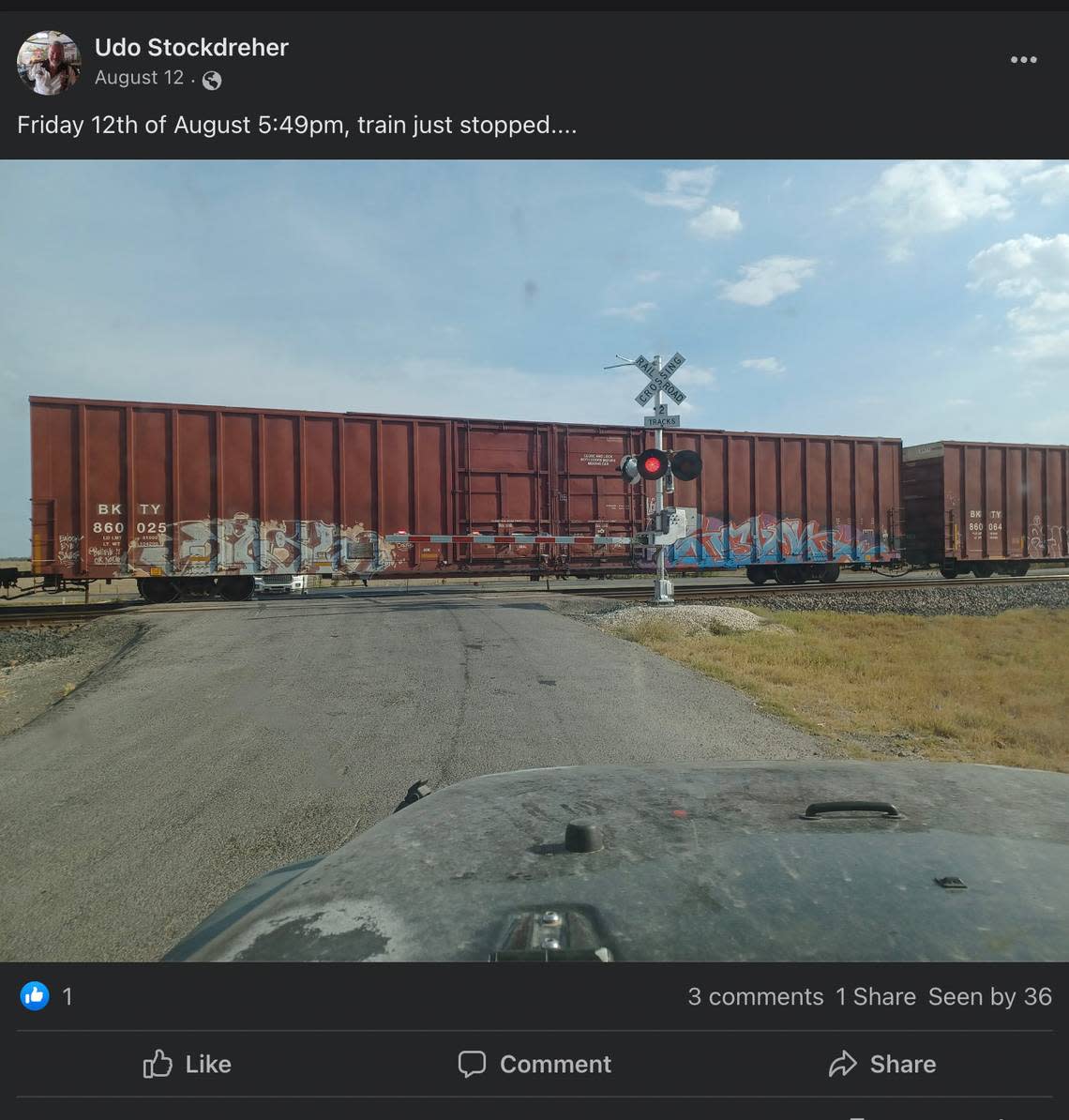

And the problem has only gotten worse in recent years for many communities across the country as the rail industry’s practices have made blocked crossings more common. According to one government report, there were nearly 1,800 reported instances in 2020 of trains blocking crossings for more than an hour, and sometimes for an entire day.

Officials in the communities that are hardest hit, many of which are predominantly minority or economically vulnerable, have grown increasingly frustrated and concerned for the safety of their citizens and the health of their local economies.

In 2017 in Forest Park, Georgia, outside Atlanta, Kate Brown and her 1-year-old son lost limbs — she a leg and he an arm — as Brown, on her way home from the bus stop, crawled under a train blocking a crossing with her baby in her arms after her two older children had crawled to safety.

“Stalled trains continue to be a tremendous burden on our residents, first responders and especially our local business owners,” Marc-Antoine Cooper, the city manager of Forest Park, told The Star. “Drivers and pedestrians in the area are forced to detour their routes, all while a large number of trains stay idle on the railway track for hours at a time.”

Tragic delays

Most of the time blocked rail crossings are merely an inconvenience. Kids are late getting home from school because a train delayed their bus. Adults can’t get to work on time. Appointments are missed, reservations canceled.

Little recognized is that these delays can turn emergencies into tragedies.

Arvid Eliason was 82 in 2017 when he hit his head and suffered a brain bleed. The ambulance taking him to the hospital was blocked for 20 minutes by a train near his home in Woodhaven, Michigan. Had he gotten treatment sooner, his son believes he might have survived.

Baldevbhai “Bobby” Patel, 46, of Wartrace, Tennessee, succumbed to a heart attack in May 2021 when trains at multiple crossings delayed an ambulance’s arrival by 12 to 15 minutes, according to the deputy emergency medical services director in the county where Wartrace is located.

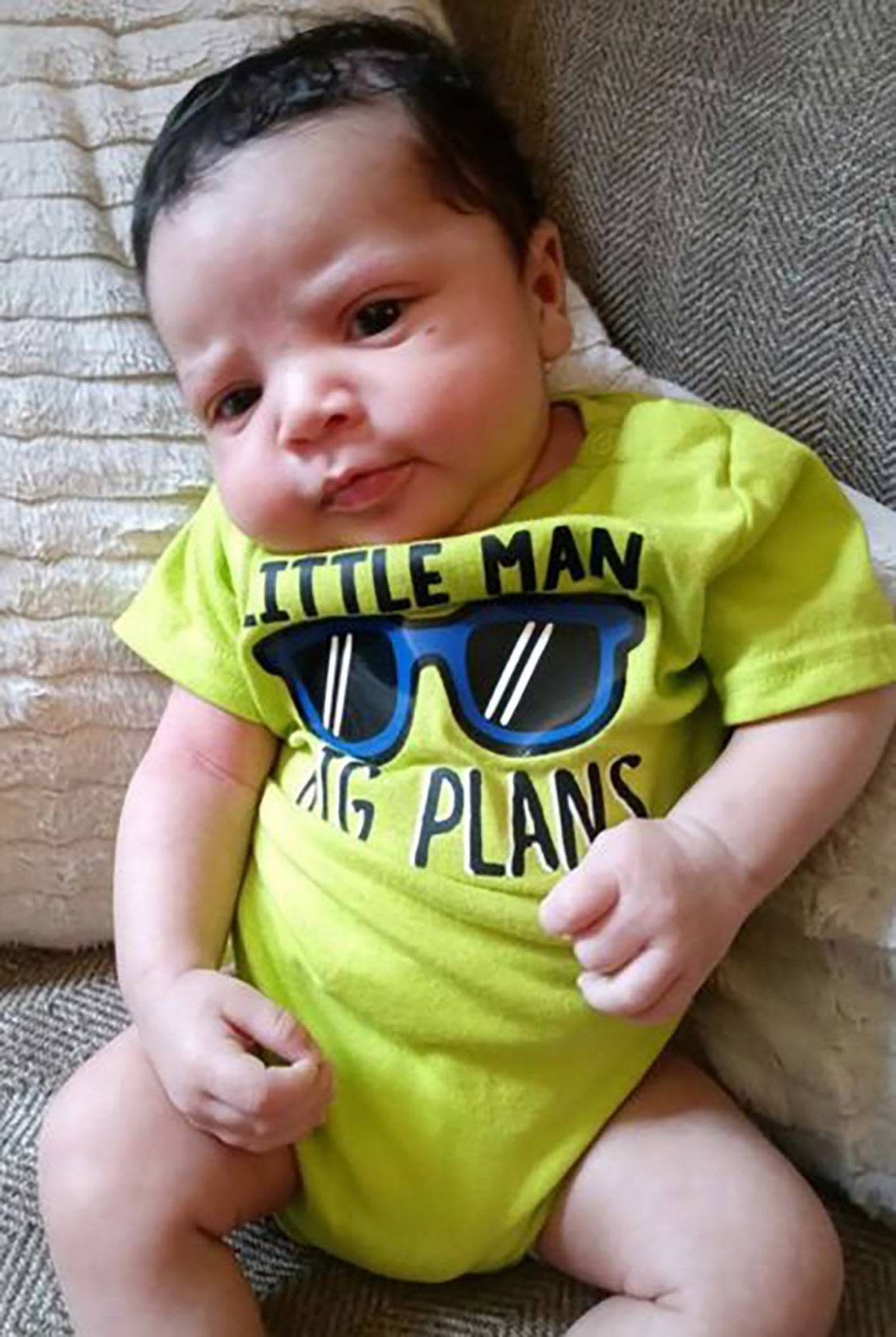

Medical treatment for K’Twon Franklin of Leggett, Texas, also came too late when rescue workers were delayed by a train blocking a crossing near his home in 2021, according to the wrongful death lawsuit his family filed in March against Union Pacific Railroad.

K’Twon was just 11 weeks old when his mother, a nurse, found him unresponsive a half hour after putting him down for a nap on Sept. 30, 2021. Finding the crossing blocked to the dead-end road where the family lived, an EMT climbed through a parked train to get the child and carry him back to the ambulance.

But before he could get back across the tracks to the vehicle, the train had begun to move. Nearly an hour passed between the 911 call and when the baby was finally loaded into the ambulance. K’Twon was pronounced dead in the hospital three days later.

“That train was always blocking the track for hours on end,” K’Twon’s mother, Monia Lee Ann Franklin, told The Star. “That morning, it was on the track for an hour, 19 minutes. And I was doing CPR for 49.”

She called her son’s death “tragic and life changing,” but hopes his passing might get someone to fix the problem so some other family can be spared her grief.

How often these tragic delays occur, no one knows for sure. No agency — local, state or federal — keeps track. But fears that it could happen in their communities have some cities and counties with heavy train traffic mounting cameras at problem rail crossings so emergency responders and the public can know in advance that they need to find another route. If there is one.

Also unknown is the number of pedestrians who are killed or maimed each year doing what that EMT in Texas did under less desperate circumstances. Weary of waiting for parked trains to move so they can get to work, school or the store, people on foot or bicycle often climb between rail cars or crawl under them at or near rail crossings all across the country.

Pedestrians maimed

Normally, no one gets hurt while putting themselves at such enormous risk. But sometimes, without warning, the trains lurch forward or backward, pinching off people’s arms and legs.

Two people were grievously injured in 2017 in Waterloo, Iowa, in separate, gruesome incidents at blocked crossings that often hem in one of the city’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods. Oneida Cosby lost both legs, while Jovida Owens was “degloved,” which is as awful as it sounds. Nearly all of the skin, along with muscle, was ripped from her neck and down her back.

“When the train’s on the tracks, it blocks the whole east side crossing,” Waterloo resident Essoria Greer told The Star.

“When the train stops, people are walking — a lot of people don’t have transportation. When they’re walking and the train just sits there for 30, 45 minutes, they have to go underneath the train, or jump the tracks with their bikes — pushing their bikes underneath just to get across the street. Anything to get across the street.”

Forty states and the District of Columbia have laws that limit how long trains can block public crossings, anywhere from five to 20 minutes, according to the Congressional Research Service. But over the past two decades railroads have successfully challenged the constitutionality of those laws, rendering them unenforceable nationwide.

State and federal courts have sided with the railroads, ruling that because Congress granted rail carriers special legal status 25 years ago, only the federal government has authority to set rules on a railroad’s operations.

Yet that same federal government has set no limits on how long a train can block a crossing. And whenever such a law is proposed in Congress, the railroad industry’s lobbyists go to work and the bill is killed.

That last happened in 2021. Rep. Jim Cooper, a Democrat from Tennessee, managed to get a blocked crossing limitation inserted into the infrastructure bill, arguing that his constituents “should not suffer because railroads think they own the world.”

But when it was all over, the blocked crossing rule was stripped from the bi-partisan infrastructure bill at the urging of the railroad industry.

“Each of the nation’s 200,000 grade crossings are different,” the Association of American Railroads said in arguing against a 10-minute limit on blocked crossings that passed the House but not the Senate. “This proposed one-size-fits-all solution will lead to unintended consequences, including network congestion and reductions in service.”

In place of a law limiting how long a train can block a public crossing, proponents were forced to accept a compromise. The infrastructure bill created a federal grant program to eliminate problem railroad crossings by building viaducts over the tracks or tunnels under them.

The program will cost American taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars — and the railroads nothing. And when money from the competitive Railroad Crossing Elimination Grant Program has run out, not every community that needs help will have gotten it.

Longer trains

Blocked crossings are increasingly creating hardships and danger for communities across the United States. Much of the blame for that rests on changes within the railroad industry over the past decade.

All of the nation’s seven largest railroads have slashed their workforces, while initiating work-rule changes that have led other workers to quit. When train crews exceed the number of hours that by law they can work, a relief crew is not always immediately available.

That means a train can sit on a siding for hours, blocking access to homes and businesses, until a fresh engineer and conductor show up for work.

Trains also have gotten longer as the railroads have looked for ways to cut operating costs and please Wall Street investors. The labor costs to operate a two-mile train are the same as what it costs to operate a train that is one mile long.

But this can lead to crossings being blocked, as the existing rail infrastructure isn’t always sufficient to support these longer trains. At 10,000 feet or more, they’re too long to park on a siding that is 8,500 feet while letting other trains pass.

So they stop on the main line, which means those other trains have to stop, too, sometimes blocking rail crossings.

Likewise, many rail yards weren’t built to accommodate these long trains. It takes more time to break trains apart when they arrive.

“If there is a log jam at point A coming into your yard, it creates a bottleneck for the whole railroad,” said Ty Dragoo, Kansas legislative director for SMART Transportation Division, a union that represents railroad workers. “And it’s just the cascading effect where we see now trains are setting on top of crossings left and right.”

While data on train length is not publicly available, two of the country’s largest railroads told the Government Accountability Office that the average length of their trains had grown 25 percent between 2008 and 2017, now averaging more than a mile long.

But some stretch as long as two to three miles and can block multiple crossings at once, as Clint McBroom, mayor of Newton, Kansas, can attest.

“We have five crossing points in Newton,” he said. “The trains are so long that all five of them can be blocked at one time.”

While Newton has alternative routes for emergency crews to get from one side of town to the other, people on foot or bicycle sometimes take the shortcut through stopped trains.

“We’ve had situations where kids (in Newton) are crawling underneath our trains in the morning and after school,” Dragoo said. “It scares the hell out of us. Because we don’t know, if we start to pull, if we’re going to cut a kid in half.”

Train crews can disconnect cars and break trains in two to make crossings passable. But often they don’t because the process of reconnecting can take a couple of hours due to federal train brake safety regulations, and time is money.

The outcry over blocked railroad crossings has grown so much in many communities that the federal government created an online portal three years ago where people can report problem crossings.

The Federal Railroad Administration, which enforces the laws Congress does pass to regulate railroads, says it uses the data to identify problem areas and assess the causes and impact of blocked crossings.

So far the FRA has issued no public report on its findings, although it’s not clear how useful a report would be. The portal only measures how often people complain about a blocked crossing, not which crossings are blocked the most.

After a while, people quit filing reports through the portal and try other tactics that they hope might produce results.

Held hostage

Allen Watts finds it more effective to make a pest of himself. He and his neighbors along Gander Slough Road outside Kingsbury, Texas, have felt like prisoners since the Union Pacific expanded a siding there to park trains, sometimes for hours, while letting other trains pass on the main line from San Antonio to Houston.

“Our emergency response comes from the west, and that’s where we’re blocked,” Watts told The Star. “I’ve harped on it (with railroad employees) and say, ‘Hey, we’re cut off from the fire department and ambulance and they (the railroad) say, ‘Well, they can go around.’

“I said, ‘So are you going to take credit for someone’s house burning? Or are you going to if someone dies, because you know that 30 minutes could mean life or death, right?’”

Watts sometimes calls the railroad dozens of times in a day when the crossing is blocked. Not until he got the phone number of a top Union Pacific executive at the company’s headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska, did relief come.

The Gander Slough Road crossing also has its own Facebook page to call attention to the problem.

Denise Wheeler-Mayo administers a similar page dedicated to a couple of crossings outside Birmingham, Alabama, calling attention to the problems the Norfolk Southern railroad causes in her neighborhood.

“We’re held hostage by the train company, you know, over and over and over again,” she told The Star. “We’ve had people die from heart attacks. We’ve had people’s houses burned because the fire truck couldn’t get to us.”

JoAnna Chamberlain of New Boston, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit, also has taken her campaign against blocked crossings online, where she promotes a change.org petition that asks that Congress step in because states are powerless to act on their own anymore.

“Michigan has legislation that says that trains can’t block for more than 15 minutes,” she said. “However, I know federal courts have said, you can’t cite trains for blocking tracks because it’s interstate commerce. So now local law won’t enforce the legislation because federal courts won’t uphold it.”

Congress needs to put people’s rights ahead of the business needs of railroads, she said.

“There are towns just like ours all across our nation experiencing the same problems,” she said. “Something must change.”

‘They just don’t care’

For more than a century, Kansas had a law on its books much like the one in Michigan. It forbade trains from blocking railroad crossings for more than 10 minutes, without leaving an opening at least 30 feet wide so vehicles can get through.

Passed in 1897 at a time when the Populists controlled state government and were trying to rein in the monopoly power of the railroads, the blocked crossing statute was one of the few of those restrictions that survived. The fines for violating the law were last updated in 2004: $100 to $600 for the first half hour a crossing is blocked and $600 for each 30 minutes thereafter.

But by then, the railroads had already begun a campaign to overturn blocked crossing laws nationwide. The BNSF Railway Co. was successful in getting the Kansas law nullified four years ago when the state court of appeals ruled the state’s blocked crossing law unenforceable.

That case grew out of one county sheriff’s frustration with BNSF for habitually blocking two crossings in a sparsely populated corner of the Flint Hills.

The Chase County Sheriff’s Department was constantly getting calls from residents who felt trapped by the trains that kept them from getting to the nearest town — or anywhere else, for that matter. One of those calls came in around 6 o’clock on a cold December morning in 2016. For what seemed like the hundredth time, a train was blocking the crossings at Norton Creek Road and county road T.

Only a few people were affected by the trains there. But for the farmers and ranchers who lived nearby, the blocked crossings had been a constant hassle. The trains would sometimes sit there for days, and there was no alternate route, only dead ends.

What if there was an emergency?

“I’ve got a half a dozen residences out there,” Sheriff Richard Dorneker said in late August as he was about to retire after 27 years with the department, 17 of them in the top job. “People are in their 80s. Got another gal that was pregnant.”

When her husband called the railroad a few years back to ask what would happen should the crossings be blocked when his wife went into labor, Dorneker said, “Their answer to him was, ‘You’ll have to leave a truck parked on the other side, and she’ll have to either crawl over the top of the train or under the train.’”

On that December morning at the center of the appeals court ruling, Dorneker drove out around 8 to find the train still sitting there two hours after the call had come in. A conductor walking alongside it said he had to check the train and offered no explanation on why it was stopped or for how long.

Dorneker asked someone back at his office to call BNSF and insist that the train be moved. When it hadn’t budged after three phone calls, Dorneker wrote BNSF a ticket and hoped that might get someone’s attention at the railroad’s headquarters in Fort Worth, Texas.

Yet rather than pay the $4,200 fine for trapping Chase County residents in their homes for much of that morning, the railroad owned by billionaire Warren Buffet’s holding company — the BNSF would go on to make a $3.6 billion profit in 2016 — chose to appeal its conviction at the district court level.

The railroad argued that states had no power to regulate its operations, and the Kansas Court of Appeals agreed. That was strictly a federal responsibility.

State laws restricting a railroads’ practices, according to the 2018 ruling, were “preempted,” a legal term that has come up again and again when it comes to state and local governments’ attempts to regulate the railroads.

So trains continue to block those crossings in Chase County for hours and hours, and there’s nothing to be done about it.

“When it comes to BNSF, they’re just gonna block what they need to block when they want to block it,” Dorneker said. “And they just don’t care. I mean, they’re not concerned about the common person that has to work or try to get to, you know, anywhere.”

The Byrd case

Two things happened that year after Gene Byrd died of a heart attack in Noble, Oklahoma.

The city of Noble, with no help from the railroad, extended the dead-end blacktop road along which Linda Byrd and her two adult children live in separate houses in a sort of family compound.

That extra half mile of asphalt now stretches to Cemetery Road, where there’s another rail crossing providing access to the homes. The project had been in the planning stages for years.

“We were paving that thing not long after Mr. Byrd’s death,” assistant city manager Robert Porton said, “so the timing was unfortunate.”

The other development was that Linda Byrd filed a wrongful death lawsuit against BNSF.

The railroad tried to get the case thrown out by having it moved from the state court where it was filed to federal district court, where the company felt it had better luck getting it dismissed. BNSF’s hope was that the federal judge would rule that Linda Byrd’s claims were preempted by a law that gives the federal government sole authority to regulate railroad operations.

But Judge Stephen P. Friot did not rule on that point, but rather returned the case to the state court for a full hearing on the issues because Byrd’s attorney had not argued that the BNSF had blocked the crossing longer than state law allowed — a law that was ruled unconstitutional a month after Byrd’s death.

Rather Byrd’s Kansas City-based attorney, Timothy Gaarder, argued that the railroad was guilty of negligence for refusing to move the train when informed that an emergency existed. The railroad and its employees, he said in a court filing, “were negligent when they permitted Train #5628 to block the Maple Street Crossing when Defendants knew, or should have known, that this could prevent a member of the public, specifically Mr. Byrd, from receiving emergency medical services.”

That’s a matter more properly heard in state court, the judge ruled, and so the case continues. While it might seem like a fine legal point, the judge’s ruling could help others navigate around the railroad’s preemption defense and successfully file negligence claims in civil cases involving blocked railroad crossings.

“There is a very real chance of having legal precedent set in this case that will either open the door to justice, or further close it,” Gaarder said.

Ultimately, it may be up to the U.S. Supreme Court to decide, if the case goes to trial, as both sides would likely appeal that initial verdict.

Which means years might pass before the final outcome is known in a lawsuit that might never have been filed in the first place, had that conductor radioed his dispatcher to say he was backing up the train 150 feet to let the ambulance pass through.

They just might have gotten there in time to save a life, Linda Byrd says.

“I mainly feel like the conductor, engineer, whatever, didn’t have a right to make that call whether Gene had a chance,” she said. “I mean, when you have a heart attack there’s only minutes that there’s a window there and he decided that he didn’t have to give that to Gene, and I just don’t understand.”

The Star’s Eric Adler and Kevin Hardy contributed to this article.