Johnson County Museum’s ‘Redlined’ exhibit is a tough, true history lesson we all need

The latest exhibit at the Johnson County Museum offers proof once more of the power, and necessity, of all of us gaining a clearer, warts-and-all understanding of our shared history here in the Kansas City region.

Some of the exhibits at the museum’s “Redlined: Cities, Suburbs and Segregation” make for difficult viewing. You’ll find familiar names there, from Jesse Clyde “J.C.” Nichols, architect of the Country Club Plaza, William B. Strang, Jr., founder of Overland Park, and the Rev. Robert H. Meneilly, a Presbyterian pastor who advocated in 1965 for integration in Prairie Village. But reading about Nichols’ and Strang’s roles in using (and shaping) the law to keep Black homeowners out of mostly white neighborhoods is bracing.

The exhibit focuses on redlining — the systematic disinvestment of African American communities across the nation. And Johnson County and Kansas City take center stage. As challenging as it may be, it’s critical for all of us to understand the role racism played in creating a legal framework where housing discrimination got baked into local and even federal law.

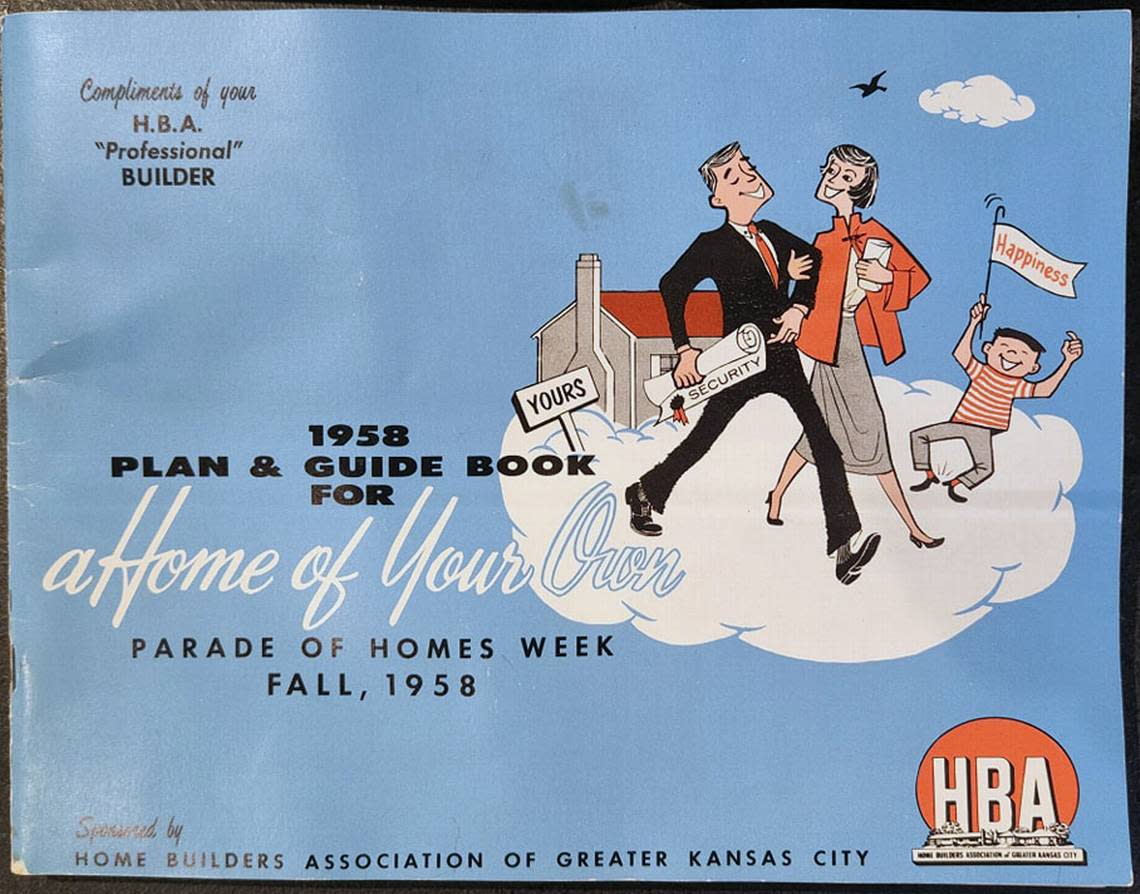

Redlining, a system perfected by Nichols, was adopted in the 1930s by the federal government and used for 35 years by the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration to exclude Black people from owning homes in mostly-white neighborhoods.

Although the segregationist policies ended with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, many of the issues that communities in the Kansas City area (and around the nation) face today connect back to redlining, as we learn through exhibit artifacts and documents.

The legacy of redlining is on full display with things such as less green space and tree cover in previously redlined communities, food deserts and no neighborhood bank offices, and a lack of access to health care and transportation. We also learn about the impact those discriminatory policies continue to have on life expectancy in the metropolitan area.

If you live in the previously redlined neighborhood from 12th Street to the 18th & Vine Jazz District, the average life expectancy at birth is 69 years. But the average life expectancy in the previously greenlined Country Club District along the state line is 85 years. The 16-year discrepancy is due to social determinants of health, including more opportunities for good education, health care access, well-paying jobs, reliable transportation, higher education and lower levels of pollution, among many other factors, museum officials said.

“There are legacies in suburban communities as well — higher home values, unaffordable housing and rents, higher performing schools,” Johnson County Museum Curator Andrew Gustafson told us. “These things continue to serve as a barrier to the suburbs, things that were intentional.”

That Strang and other major developers brazenly embraced Nichols’ methods of placing deed restrictions on developments to keep Black people out is eye-opening. And yet, Strang Line Road and Strang Park in Johnson County are named in his honor. Other facilities in Johnson County bear his name as well. It’s fair to ask whether that should remain the case.

In a 1965 sermon, the Rev. Bob Meneilly, founding pastor of Village Presbyterian Church in Prairie Village, preached to his growing congregation about the importance of welcoming Black neighbors into their Johnson County communities, according to the exhibit.

His lectures made front-page news. He faced backlash, but the church’s congregation grew into one of the largest in the area. Meneilly’s fight for equality offers an example of how each of us can stand up for the rights of others.

This is history that did not happen far away, or in bigger cities on the coasts. This history happened right here in Kansas City and Johnson County. This area did as much shaping of these policies and practices as any.

On display until January inside the Johnson County Arts and Heritage Center, the exhibit is one not to miss. Do yourself a favor and go. Take family and friends, too.