Jersey Shore towns join suit over toxic chemicals in drinking water

A group of pollutants known as "forever chemicals" are so widespread in New Jersey's environment that a group of local water suppliers are suing companies that manufacture and use large amounts of the chemicals in their products.

Water suppliers in Brick, Toms River, Wall and other communities across the state say a group of chemicals known as PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) have contaminated their drinking water supplies.

PFAS are used in high concentrations in firefighting foam, which then leaches into groundwater and then the drinking water supply.

Studies have shown that even in minuscule amounts, PFAS can cause health impacts. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the chemicals are known to increase risks for certain types of cancer, raise blood pressure and decrease fertility.

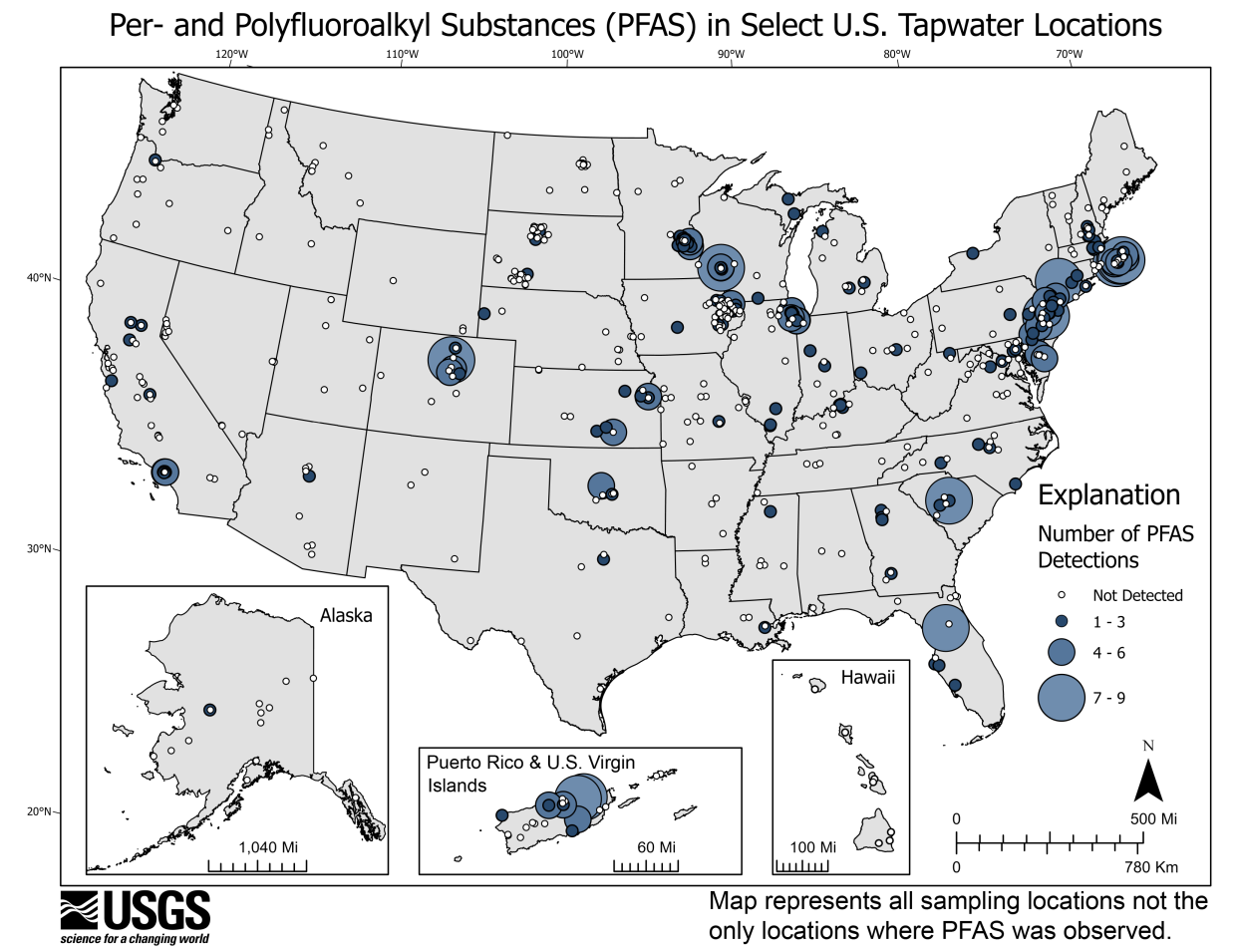

Earlier this year, the U.S. Geological Survey announced that at least 45% of the tap water in the United States contained PFAS.

The heat- and grease-resistant chemicals are also used in many everyday products, such as nonstick cookware, food packaging, paints and varnishes, electronics and stain-resistant furniture and carpet coatings.

PFAS are now so widespread in the environment that a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found the chemicals were accumulating in the blood of nearly every person tested.

Water suppliers in New Jersey, along with others across the country, joined a multidistrict lawsuit filed in a U.S. District Court in South Carolina that blames PFAS for polluting their drinking water, according to the Environmental Litigation Group, an Alabama-based law firm that represents plaintiffs in New Jersey.

Every lawsuit involving PFAS in the nation winds up in the South Carolina court, said Yahn Olson, an attorney with the Environmental Litigation Group. The firm's cases include claims from numerous New Jersey public water authorities and firefighting groups that blame contamination on companies that manufacture and use large amounts of PFAS in their products.

The multidistrict lawsuit bundles these cases with roughly 500 others from across the country focused on PFAS.

"When you're suing a large company… it obviously requires a lot of resources and (a multidistrict lawsuit) allows plaintiffs (and) firms to pool their resources," Olson said.

"If you took one plaintiff to claim they were exposed to PFAS and it led to cancer, they really wouldn't have the resources to fight all these big (chemical) companies by themselves," he said. "So the big thing it does is it allows everybody to put their claims in once and fight together."

In Wall Township, levels of PFAS chemicals in drinking water were more than four times the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's safe exposure limit, according to the Environmental Litigation Group.

In Brick, PFAS levels were 3.25 times over the federal standard, according to the law firm. The township's water supply contained two other closely related chemical contaminants: PFOA, or perfluorooctanoic acid used in nonstick and stain-resistant products, and a group of grease- and water-resistant chemicals known as PFBS, or perfluorobutanesulfonic acid, according to the firm.

Water authority officials in both townships could not be immediately reached for comment.

Some experts say even low levels of PFAS exposure are unsafe for vulnerable people. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and the Minnesota Department of Health, which have studied PFAS since 2002, found even low levels of PFAS over years of exposure led to impacts on vulnerable people.

Erik D. Olson, senior strategic director of food and health at the National Resource Defense Council, said "extremely low levels" of PFAS exposure harmed human health.

In 2022, the EPA released nonbinding health advisories on PFAS, warning that two particular types found in cardboard packaging and firefighting foams (PFOA and PFOS) showed health impacts at minuscule amounts, according to the Associated Press.

Why PFAS are dangerous

Although the scientific community's knowledge of how PFAS impact the human body is evolving, the chemicals are known to increase risks for certain types of cancer, raise blood pressure and decrease fertility, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The chemicals also lower the body's ability to fight off infection, interfere with vaccine effectiveness, accelerate puberty, cause developmental delays, increase cholesterol and raise the risk of obesity, according to the agency.

PFAS are known as forever chemicals because they do not degrade in the environment or body, according to the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Resistant to grease, heat and water, PFAS are a common component in certain firefighting foams. Because these foams are commonly used in training exercises and emergencies at military bases, airports, shipyards, chemical plants and firefighter training centers, they are common in the environment around these places, according to the EPA.

PFAS are also used in a variety of other everyday products, such as food packaging, clothing, cosmetics and toilet paper, according to the Chan school. The chemicals are also in stain-resistant carpet and furniture coatings, nonstick cookware, cleaning products, paints, varnishes and some electronics, according to the EPA.

"It's been in so many consumer goods," said Olson, with the Environmental Litigation Group.

However, much of the environmental contamination stems from PFAS use in firefighting foams, he said.

"It's used to fight oil-based fires and gasoline (fires)," the attorney said. "It (firefighting foam) is highly concentrated with PFAS. Your average firefighter, they're working in the fire station. They're storing that stuff. The dust gets into their food, gets into the water, and they're getting sprayed with it and they're all just totally immersed in foam sometimes."

Exposure can lead to kidney cancer, testicular cancer, hormone problems and thyroid diseases, among other serious health problems, Olson said.

"We have all these individuals who unknowingly were drinking contaminated water, or firefighters who were using all this (PFAS) foam all the time," said Olson. "And they've got horrible cancers and horrible injuries."

Water treatment agencies and municipalities participating in the multi-district lawsuit in South Carolina are seeking payment from chemical companies for filters and remediation costs to remove PFAS and related forever chemicals from drinking water supplies, Olson said. The plaintiffs, such as firefighters, who suffered physical or medical harm are suing to cover medical costs and seek other punitive damages, he said.

In December, New Jersey lawmakers moved to ban forever chemicals in firefighting foam and directed the state Department of Environmental Protection to create a disposal program.

In 2020, the state set drinking water standards on three PFAS chemicals. Officials with the Department of Environmental Protection declined to comment on PFAS, citing the multidistrict litigation and pending settlement agreements.

The federal EPA is also taking action on PFAS. In October, the EPA released a new rule requiring companies to report PFAS information to the agency's Toxics Release Inventory program, even when the chemicals are used in small quantities. Previous rules allowed exemptions when small amounts of the chemicals were used.

The PFAS legal fight

Water departments in Wall and Brick, among others in New Jersey, are seeking damages from chemical companies that manufacturer PFAS. Defendants named in the multidistrict lawsuit include 3M, BASF, Bayer, Dupont, Honeywell International, the Middlesex County Fire Marshal, Tyco Fire Products, as well as numerous manufacturers of the chemicals and firefighting foam and equipment.

On its website, 3M said PFAS-based products are crucial for making cars and airplanes, where the chemicals protect fuel lines, electronics and equipment; are used in solar panels, windmills and fuel cells; and are used in medical devices and common prescription medicines.

The company said it would stop manufacturing PFAS by the end of 2025 and would switch to alternatives in its products where available. However, the company noted that some continued, limited use of PFAS might still be necessary in some circumstances.

Earlier this year, the company agreed to pay more than $10 billion in a settlement over the water contamination from firefighting foam and other PFAS-containing products, according to The Associated Press. On its website, 3M said that PFAS' net sales are valued at around $1.3 billion, or 4% of the company's annual revenue.

Other local water systems across Monmouth and Ocean counties filed claims about PFAS in their drinking water supply. Water providers in Toms River, Sea Girt, Point Pleasant, Point Pleasant Beach, Spring Lake, Red Bank, Manasquan, Marlboro, Manchester, Keansburg and the New Jersey American Water supply in Monmouth and northern Ocean counties also filed claims.

Like 3M, chemical companies Dupont, Chemours and Corteva also agreed to pay nearly $1.2 billion for PFAS contamination in public water systems, according to Dupont.

"Once it (PFAS) gets into the waterway, you can filter it out with some, some very expensive and specialty filters," he said. "But other than that, there's really no way to get rid of it."

The two settlement agreements are still subject to final approval from U.S. District Court Judge Richard M. Gergel.

Amanda Oglesby is an Ocean County native who covers education and the environment. She has worked for the Press for more than a decade. Reach her at @OglesbyAPP, aoglesby@gannettnj.com or 732-557-5701.

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: PFAS chemicals in Jersey Shore towns' drinking water led to 'horrible cancers'