Invisible danger? Some NC communities live with higher pollution exposure risks.

From the west Charlotte street where Sharrone Robinson lives, it’s impossible to tell that the neighborhood is flanked on three sides — four, when you consider the sky — by some of the biggest concentrations of air pollution sources in Mecklenburg County.

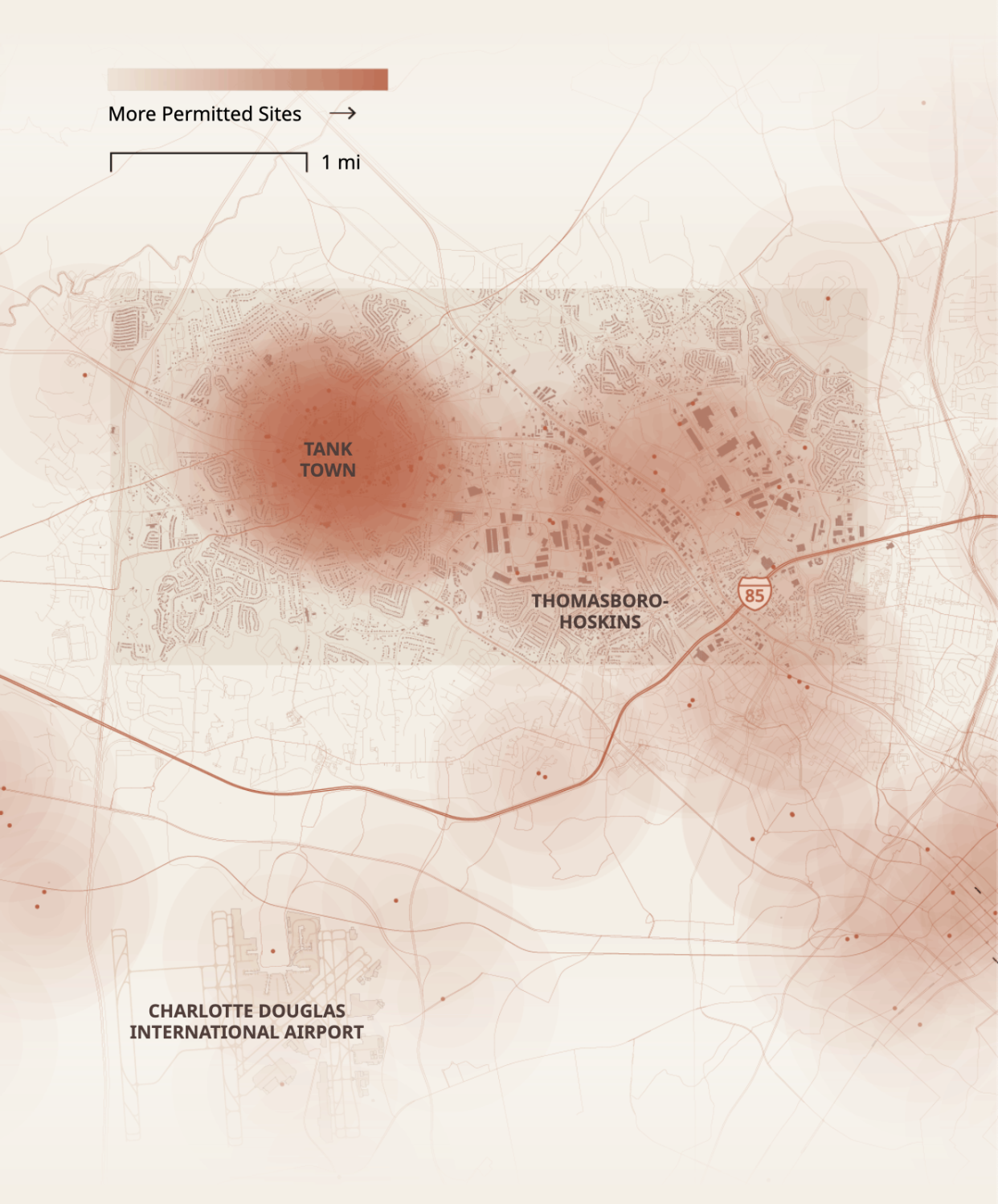

A mile north is “Tank Town,” block after block of 100 massive white or green petroleum tanks that house the fuel that keeps Charlotte, its airport and other cities running.

Two miles east is Interstate 85, where 100,000 vehicles a day whiz along eight lanes of traffic, according to the N.C. Department of Transportation.

And three miles south lies Charlotte Douglas International Airport, which Airports Council International ranks fifth in the world in air traffic, with 1,400 incoming and outgoing flights per day as of 2021.

“These are great sources of pollution,” said Robinson, a CleanAIRE NC volunteer who has an air quality monitor hanging on the side of her house. “These have cumulative impacts to human health and the environment.”

But when the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality considers air, water or other permits to allow the release of limited pollution, it rarely assesses all of the other pollutants close by. Nor does it usually assess how adding a new pollution source could disproportionately burden people living in the area.

This is a common approach to environmental permitting. States like Maryland and New Jersey have recently passed rules requiring their regulators to consider the surroundings when deciding whether to grant permission to pollute, but they are in the minority.

Environmental justice advocates are pushing North Carolina regulators to consider these broader impacts, something Democratic Governor Roy Cooper’s administration has, to a degree, tuned in to.

Most discussion here focuses on cumulative exposure risks in rural areas, especially on neighbors of industrial-sized pig and poultry farms. But plenty of people in urban corridors live near multiple sources of pollution too, a data analysis by The Charlotte Observer and The News & Observer revealed.

In addition to those exposures, people in and near cities are more likely to live with non-permitted exposure hazards, such as potentially harmful particles emitted by tailpipes on busy highways, jet engines landing at nearby airports or heavy machinery at construction sites.

And residents in some urban areas, Mecklenburg County included, live with higher risks than others across the nation of developing cancer from the air they breathe, EPA data shows.

“If we are prioritizing the health of our residents, then we need to be thinking about those burdens,” said Virginia Guidry, head of the state Occupational & Environmental Epidemiology Division.

Reality of pollution control

Air and water permits are legally binding agreements. They specify required pollution control equipment at sites, the limited amounts of regulated pollution that can be released there and how emissions will be monitored.

Some 4,000 largely urban sources of contamination, such as coal ash and Superfund sites, or industrial facilities that hold a permit to pollute, dot North Carolina, an analysis by the Charlotte Observer and The News & Observer found. In rural areas, there are another 2,500 permits for animal operations and 4,700 industrial-scale poultry farms that aren’t inspected but are “deemed” permitted.

Ninety-eight of the state’s 100 counties have a facility with a permit that allows it to release a limited amount of pollution into the air, data show. All 100 counties have a facility permitted to release pollutants into water. Many times, these are water or wastewater treatment plants. Mecklenburg County has the most sites holding a water permit with 43. Wake County has 29.

About 75 census tracts, areas the size of neighborhoods, have at least two polluters per square mile, the newspapers’ analysis found. Combined, those tracts are home to more than 200,000 people.

These operate legally under state law. But their combined potential risks are, for the most part, invisible to regulators and people living nearby.

“To look at permits in isolation – as if this is the only facility that is going to be impacting the community – literally ignores all the impacts in that community that are already existing and the particularities of that community,” Jasmine Washington, a Southern Environmental Law Center attorney, said.

For example, drive along I-85

Interstate 85 connects North Carolina’s two most populated urban centers — the Charlotte area and the Triangle. Along the highway are industrial neighborhoods packed with sites permitted to release contaminants into the air and water.

Here are a few examples, traveling south to north.

A neighborhood around Robinson’s home, between Brookshire Boulevard and Freedom Drive, has seven facilities permitted to pollute the air and four that pollute the water. Other permit holders sit just outside her community.

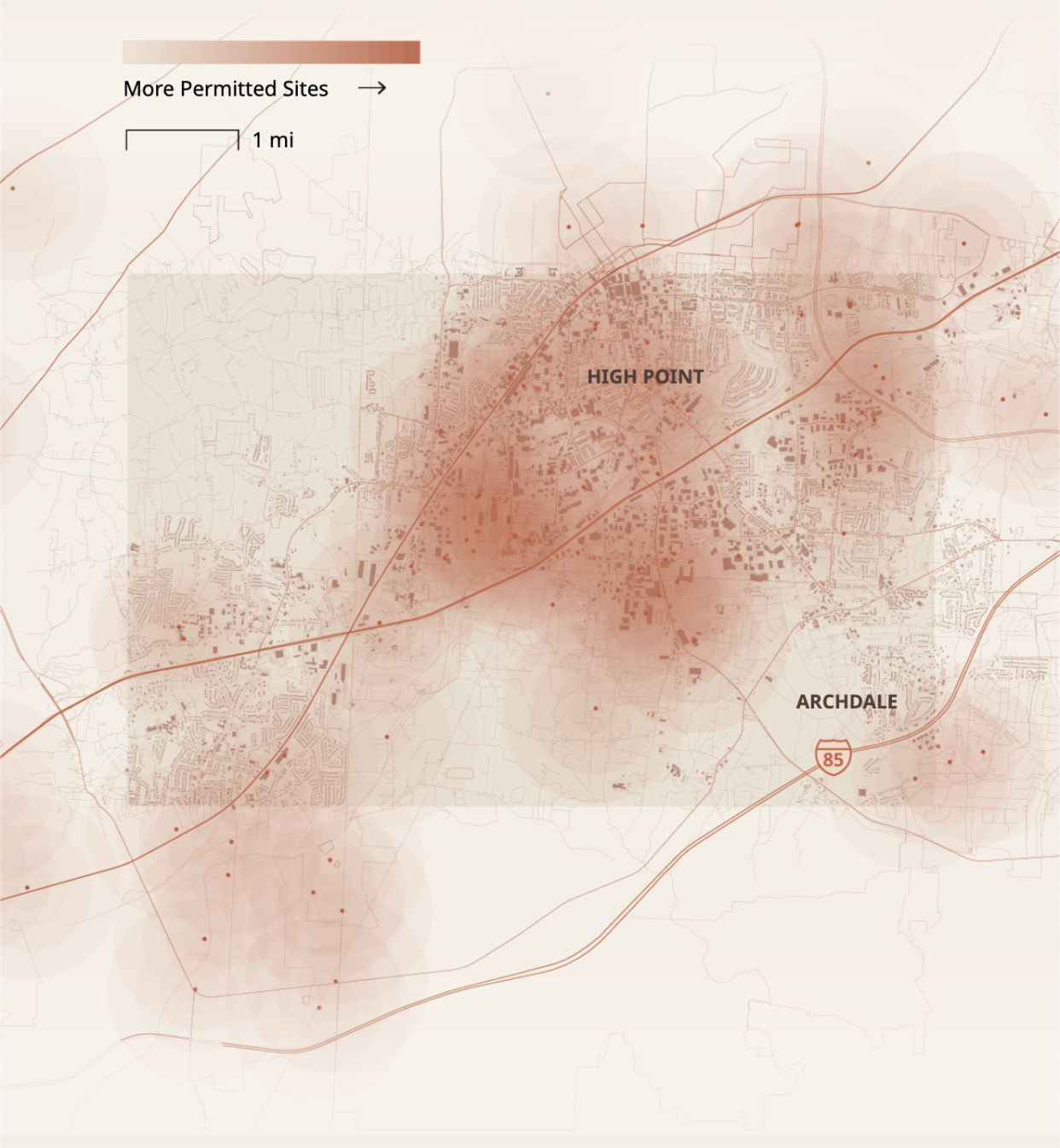

North on I-85, a High Point neighborhood hosts 13 facilities permitted to pollute the air, with seven allowed to release limited amounts of toxic chemicals, according to the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory.

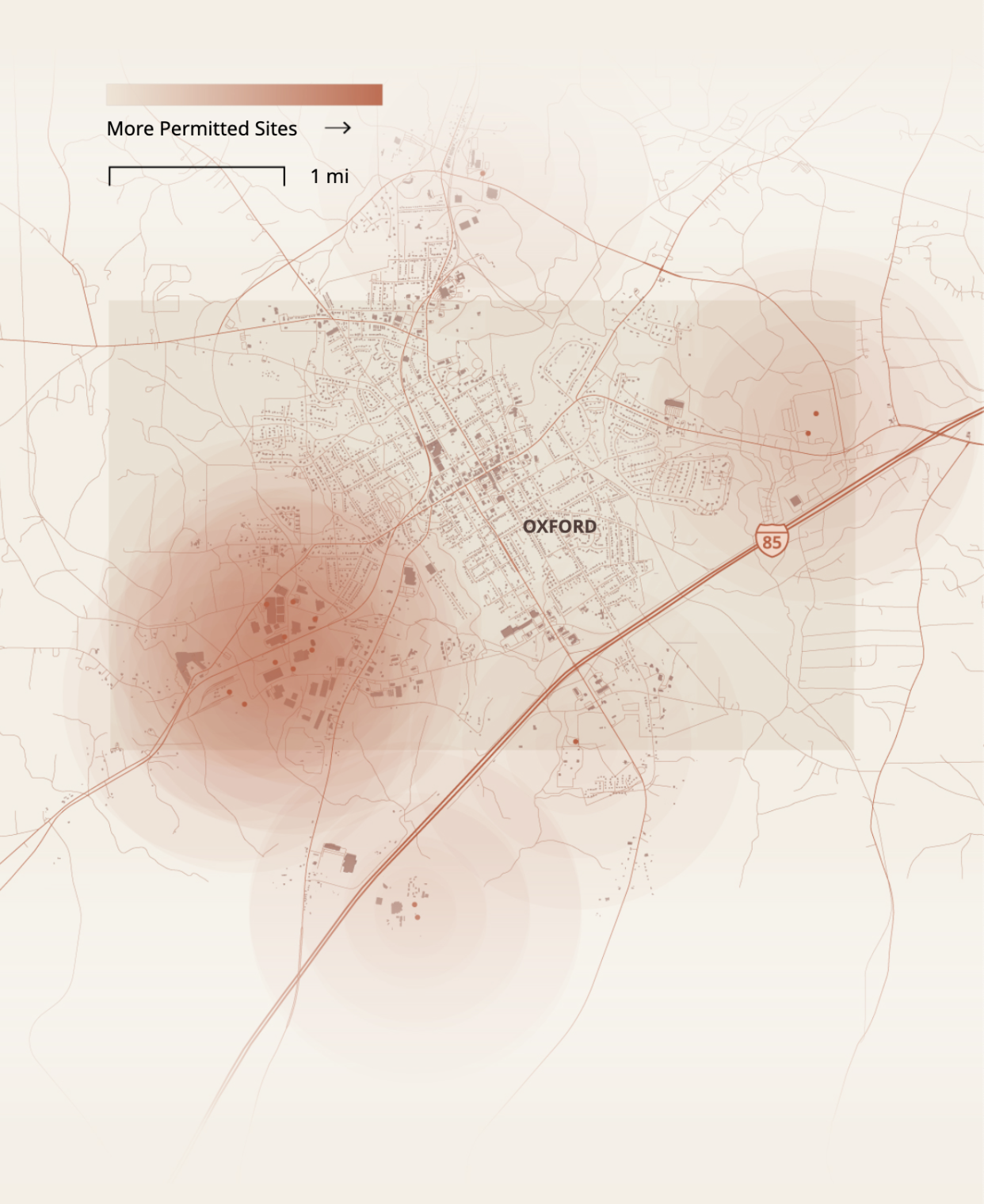

In Granville County, near the Virginia border, one neighborhood hosts three facilities permitted to pollute the air, one that pollutes the water, two Superfund sites and four sites that release toxic chemicals, the newspapers found.

Although the known health risks in these areas fall within the EPA’s acceptable levels, residents of each area have a higher risk than most of the U.S. of breathing toxic air, inhaling particulate matter and living near hazardous waste, EPA data shows.

And each is home to a higher percentage of Black residents and people with lower median household income than the state average, according to the census. That’s too often the case, say people working to address the disproportionate exposure to hazards by these populations in the U.S.

“Nobody wants to have their family being disproportionately burdened with so much pollution and having to suffer the health consequences of industry choosing the path of least resistance,” Amanda Strawderman, environmental justice manager for CleanAIRE NC, a nonprofit based in Mecklenburg County, said.

Trouble spot in High Point?

Southwest High Point has more toxic release permits than any other neighborhood in the state. This is a place where Thomas Built has manufactured buses for more than a hundred years, where AkzoNobel makes wood coatings and where Kao Specialties Americas manufactures several chemicals including a concrete additive and toner binder.

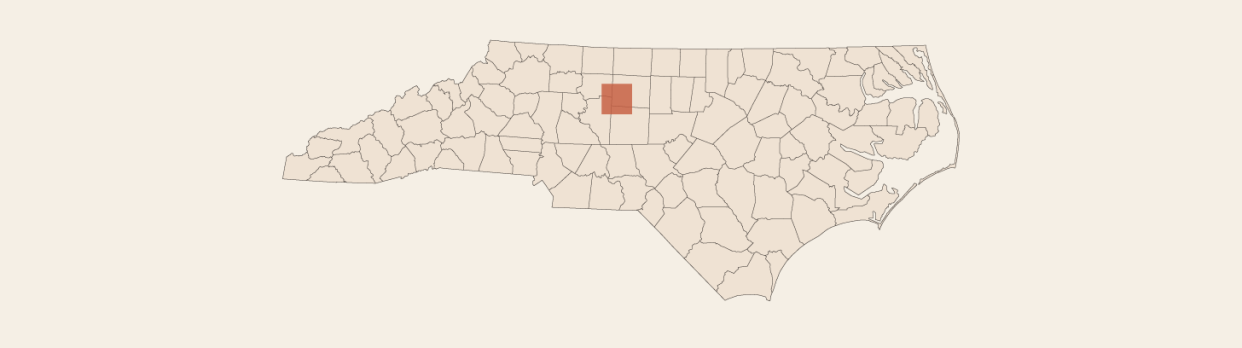

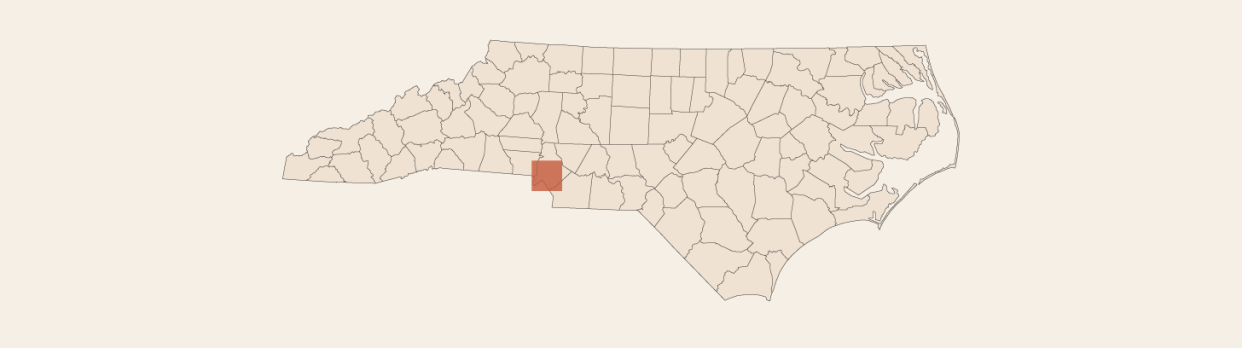

These maps show some of the most dense concentrations of air and water pollution permits granted by environmental regulators in North Carolina. Heavier shading shows closer proximity to more sources of pollution.

Denise and Johnny Horne’s entire lives have unfurled around the Southside Recreation Center in High Point near that industrial cluster.

The meeting place and gymnasium sit next to the creek where Johnny swam as a boy, knowing enough to stay out when oil slicks floated downstream. Recent water testing by an N.C. State University professor found the presence of human waste in that same creek.

Where the Hornes first met more than five decades ago is now the yard of the recreation center. Some 900 feet to the south sits the community garden the Hornes have tended for about 20 years. It’s one of the only sources of fresh vegetables in the Southside neighborhood, which the U.S. Department of Agriculture officially designates a food desert.

But walk north on an adjacent greenway about 850 feet and expect to get walloped by a sharp odor that smells like burning plastic. Take a few more steps and the source becomes clear: Innospec, a chemical manufacturer tucked behind a nearby fence. This odor clings, which is why Denise Horne doesn’t dry her laundry outside anymore.

“It’s like a real stale smell,” Johnny Horne said.

The Hornes’ house was among 70 on the south side where UNC-Greensboro researchers sampled the drinking water in 2017. It’s one of 29 homes where tests detected chromium levels exceeding the EPA’s drinking water standards.

Researchers also found elevated levels of mercury in five homes and lead in two houses.

Denise Horne has never trusted her drinking water. She’s always preferred bottled water to what comes out of the tap, which she sometimes boils before cooking with it.

“Sometimes you can turn the faucet on and smell a smell coming from the water,” she said.

All of what the Hornes live with, the lack of a local grocery store and the existing pollution, is important to consider when assessing cumulative impacts, experts say. That’s because they can shape whether an area’s residents are more likely to suffer health effects from any added environmental pollution.

Tony Collins, the former president of the Southside Neighborhood Association, doesn’t oppose having job-supplying factories nearby. But he also wants to know if they have any negative impacts.

Ideally, he said, researchers would be able to access more funding to figure out if anything is in the air residents are breathing and the water they are drinking. Anything those researchers find would need to be shared with the community, added Collins, who also co-chairs the board of the non-profit Southwest Renewal Foundation.

“It persists,” Collins said of pollution. “There are a lot of questions.”

A push for change nationally, in NC

The federal government has long been aware of cumulative risks from pollution and is paying increased attention to the threat under EPA Administrator Michael Regan, who was North Carolina’s chief environmental regulator from 2017 to early 2021.

The agency defines cumulative impacts as the total exposure to either chemical or nonchemical “stressors” that could impact health, quality of life or well-being in a late 2022 research planning document. Those stressors can include exposures to air and water pollution, but also things like proximity to a highway or limited access to healthcare.

The agency has pledged to spend more on measuring cumulative impacts between 2022 and 2026. It has also released updated guidance about how it and states that grant permits could consider the multiple exposures to pollution.

In 2022, Cooper signed Executive Order 246 requiring state agencies to appoint a point person for environmental justice efforts, to provide more information to the public about ways they have contributed to disproportionate impacts and how they could reduce them.

Cooper pledged to “identify and prioritize” additional concerns about the uneven impacts of pollution, including cumulative impacts.

There’s one problem, experts say.

Without the cooperation of a Republican-controlled General Assembly, Cooper administration officials argue, the governor cannot mandate that DEQ weigh the risk of cumulative impacts when making permitting decisions.

Regulators are required to grant permits that meet certain criteria, even if they add to existing burdens, said Peter Ledford, Cooper’s clean energy director.

“DEQ’s hands are bound by the laws that are adopted by the General Assembly. Many of these laws provide DEQ with very little latitude. DEQ must issue permits under most circumstances, and that is keeping DEQ from being able to evaluate the cumulative impacts,” Ledford said.

Some environmental attorneys in North Carolina disagree with DEQ’s interpretation of permitting laws, arguing they give the agency much more power than it’s willing to exercise to consider the full scope of cumulative impacts.

Since gaining control of the General Assembly more than a decade ago, Republicans have cut positions at DEQ and sought to decrease regulatory burdens.

A pair of bills introduced by Democratic lawmakers in the House this session that would explicitly require DEQ to consider cumulative impacts have languished in that chamber. Those bills are unlikely to become law this session, said Rep. Frank Iler, a Brunswick County Republican who co-chairs the House Environment Committee.

It is “worrying” that the bills seemed to echo the Democratic Party’s environment justice stance and that their passage could make it too easy for agencies like DEQ to deny permits, he said of the proposed legislation. “It’s already difficult to get permitted in some cases — which is not a bad thing, which can be good — but this would add more layers of bureaucracy and difficulty on the lines of trying to develop different areas,” Iler said. Sen.

Brent Jackson, who co-chairs the Senate Agriculture, Energy and Natural Resources Committee, declined this week to comment on the push for the state to consider cumulative impacts. Jackson, a Sampson County Republican, said a reporter’s question was the first he’d heard of the concept.

More protections elsewhere

New Jersey and New York have both passed laws within the past year requiring environmental officials to consider how communities are already bearing the burden of pollution when evaluating whether to approve new permits.

The New Jersey rule requires environmental regulators to deny a permit if it would worsen already disproportionate impacts from pollution when compared to the rest of the state. Facilities must decrease those burdens or risk not receiving permits.

By comparison, North Carolina regulators can consider limited types of nearby pollution in only some cases.

DEQ’s water discharge permits, for example, must weigh whether a new discharge will cause pollution levels downstream to rise above state limits set to protect drinking water.

And facilities that want to emit at least 10 tons of a single chemical or 25 total tons of chemicals the EPA says are hazardous annually trigger an analysis of how they will impact nearby air quality only. That’s done to make sure what’s proposed won’t increase pollution above national air quality standards, what the EPA calls “a limited form of a cumulative impacts analysis.”

The kind of analysis environmental groups are seeking would account for more sources while also accounting for the disproportionate exposures to pollution, said Blakely Hildebrand, a Southern Environmental Law Center senior attorney.

The only time North Carolina regulators have explicit power to deny permits based on such a cumulative impact assessment is for solid waste facilities like landfills, a requirement of a 2007 state law.

The DEQ declined several requests to interview Elizabeth Biser, the agency’s secretary, on this topic. The agency complies with civil rights laws despite the department’s stance that it is unable to deny most permits on the basis of cumulative impact analyses, DEQ spokeswoman Sharon Martin wrote in an email response to questions.

State health officials spotlight risks

State health officials don’t grant environmental permits. But they do track data that measures some health effects associated with pollution across North Carolina.

Responding to requests by community groups, the state’s Occupational & Environmental Epidemiology Division is creating a website to share how exposure to multiple pollutants is impacting health, Guidry said.

DHHS officials hope users will be able to zoom in on their address and see what sources of pollution are nearby. Another dashboard the agency is developing allows people to see county-level information about health conditions like rates of asthma and cancer and environmental data like toxic releases or days with high ozone levels.

The goal, Guidry said, is to merge environmental health concern data with demographic information to identify communities suffering from cumulative impacts. The new tools could help local residents and governments shape permitting and zoning decisions.

The department, along with the NC Environmental Justice Network and the NC Conservation Network, is working with as many as 10 counties to include a chapter on cumulative impacts in their community health assessments — reports created every four years that investigate effects on residents’ health.

“It will provide more of a lens on issues of inequity within specific communities that may have been underserved up to this point,” said Joe Bowman, an emergency preparedness and environmental health nurse consultant.

Embracing industry, jobs

Even on the fringes of urban areas, families live near multiple sites granted permission to emit regulated pollutants into the air and water.

On the southwestern corner of Oxford, Industry Drive offers close proximity to Interstate 85 for a cluster of low-slung factories. Zippers are made at one, tread rubber for tires at another and roof shingles at yet another.

State regulators have issued more toxic release permits in this census tract than any other in the Triangle region. The surrounding area also hosts two Superfund sites, a lingering reminder of how manufacturing can have long-standing repercussions.

Superfund sites are places that the EPA finds to have been contaminated with hazardous waste. The pair of Superfund sites on Oxford’s Industry Drive include Cristex Drum, a former textile mill where chemicals used to dye nylon yarns contaminated groundwater and soil, as well as a former antenna manufacturer where sludge that was used to treat metal was dumped into an on-site lagoon causing groundwater and soil contamination.

A quiet neighborhood sits less than half a mile away from Industry Drive, a collection of ranch and split-level homes are set back on large lots. Most every yard was well trimmed and children rode their bikes freely from house to house on a spring afternoon.

Larry Ramsey moved to the Oxford neighborhood about 50 years ago. He spent decades working at different plants up and down Industry Drive.

Like many of his neighbors, Ramsey has never given the factories’ proximity to home a second thought.

“If they’ve had problems with pollution or anything like that, I haven’t heard it,” Ramsey said.

But at least one neighbor is wary of how close they live to an industrial area. Chekesha Jones has lived on East Dale Drive for about 16 years.

Even though her drinking water comes from the city, Jones worries about what is in it.

In that entire time, she has not touched the water that comes out of her taps. She reluctantly uses it to brush her teeth.

Asked why, Jones said: “All the factories.”

A legacy built over years

Clusters of permitted facilities emerge over years. “Tank Town” and the Charlotte airport have been there longer than some residents living around them can remember.

As the years went on, the tank farm grew and other industries, such as a wood manufacturer and concrete supplier, got permits of their own. Many of the air permits active there have histories that date back decades.

The tanks hold ethanol and petroleum and sit near hangers that pump fuel into trucks. These and other operations are permitted to release limited amounts of regulated pollutants that most people are unfamiliar with, including benzene and xylene.

Robinson, the CleanAIRE NC volunteer, lives among some of the densest clusters of potential air and water contamination in Mecklenburg County, according to the Charlotte Observer and News & Observer analysis.

In the few miles between the airport and “Tank Town,” are more than 20 sites with a permit to discharge pollutants into the air or water or sites that the federal government has labeled as contaminated.

The EPA’s environmental justice screening tool shows residents in the west Charlotte area live with higher risks than others across the nation of developing cancer from the air they breathe, though that risk falls within levels the EPA deems acceptable.

“Why should we continue to overburden communities that already have the pollution and poor health outcomes,” asked Kirsten Minor, health manager at CleanAire NC.

One permit holder in “Tank Town” is Colonial Pipeline. In an email response to questions about the push for considering all nearby exposures before granting permits, a spokesperson stressed that Colonial complies with all regulatory requirements, including cumulative impact reviews in some states.

“Any changes in permitting policy should be aimed at maintaining a fair and consistent approach that ensures we can continue safely and reliably serving the nation’s energy needs while meeting or exceeding all regulatory requirements,” the statement read.

The air around “Tank Town,” and all of Mecklenburg County, for that matter, meet EPA standards, stressed Megan Green, the county’s air quality program manager.

In fact, the county’s air quality has improved dramatically in recent decades, Green said, thanks in part to tougher standards on vehicle and smokestack emissions and the county’s grant program to replace old diesel engines.

The number of “good” air quality days jumped from 111 in 2007 to 270 in 2022, county records show. Good days, affected by the weather and amount of pollution, mean no negative health impacts are expected from the quality of the air.

Perhaps that’s why most of the people who live near “Tank Town” or under the rumbling engines of the airplanes who agreed to speak with a reporter said they don’t mind the industries.

“These people operate in a way that is reasonable for the environment and does not create issues and hazards for the people who live out here,” said Chad Derrick, 52, who lives less than a mile from the petroleum tanks.

But every now and then, residents get reminded that this place is different.

A half mile from a dozen tanks is Thrift Baptist Church, where Gene Lathan has been the pastor for more than two decades. For years, he stored his RV nearby off Wilkinson Boulevard, under a common flight path for planes going in and out of Charlotte.

Lathan never questioned the air quality there, he said. But on a trip to Myrtle Beach in 2019, a worker was cleaning the roof of Lathan’s RV when he asked the pastor if he lived near an airport.

Lathan wondered: How did he know that?

The man said any time he’s seen an RV with so much soot caked onto its roof, the owner kept the vehicle near an airport.

“Something turned my roof black,” Lathan said. “If it can do that to your roof, certainly there’s a concern about breathing it.”

Sources

Data: The Charlotte Observer and The News & Observer analysis; EPA; NC DEQ; Mecklenburg, Forsyth and Bumcombe counties | Maps: OpenStreetMap; Google Earth

Acknowledgments

Video production by Sohail Al-Jamea of McClatchy | Data visualization by Susan Merriam of McClatchy | Development by David Newcomb of McClatchy

Kozik Environmental Justice Reporting Grants, supported by the National Press Foundation and the National Press Club Journalism Institute, helped fund this reporting. So did the 1Earth Fund and Journalism Funding Partners, which support climate and environment reporting at The News & Observer. McClatchy maintains full editorial control of all philanthropy supported reporting.