Inside the world of championship cheese judging: supertasters, palate cleansers and puns

MADISON − Inspect. Smell. Chew. Spit. Score. Repeat.

It's the rhythm of the World Championship Cheese Contest. Dean Sommer ran through this routine 118 times over two days as he methodically evaluated gouda, goat's milk, mozzarella and more. He and 53 other judges worked their way through more than 3,300 entries this week.

It may sound like a dream job to many living in this cheese-loving state. For the judges, however, the stakes of this unpaid, volunteer gig are real.

"It is a job," Sommer said of judging the biennial contest. "You take it extremely seriously. There's a lot riding on the results of the contest."

The grand champion gets enormous publicity. Winners in each class receive bragging rights. Other cheesemakers use the judges' feedback to make their products even better for the next contest.

The judges will return to their day jobs. But for three days every two years, they are the big cheese in town.

Different career paths can lead to judging invite

What does it take to join the elite cheese judging group? There's no application. Just an invitation from the Madison-based Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association, which has hosted the world championship since 1957.

Many judges grew up in the cheesemaking industry and said they never considered another career choice.

"You don't get into it — you're born into it," said Adrian Fowler, a 14th-generation cheesemaker from England who judged cheddar and other categories this week. Cheesemaking comes with some job security. "Everybody's got to eat!"

Academia is another route into the judging world.

Arnoldo Lopez-Hernandez grew up in Mexico and has a chemical engineering background. He became involved in cheese after he started teaching food science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He started judging at the world championships a decade ago.

Also from UW-Madison is John Jaeggi, whose grandfather immigrated from Switzerland in the 1920s and started a Swiss cheese plant in Monroe County. Jeaggi remembers sitting under a table as a 7-year-old "mesmerized" by the process and sneaking samples.

Jaeggi has worked for UW's Center for Dairy Research since 1991, helping cheese companies around the world on product development. He and others at the center, including Sommer, are often tapped to evaluate less common cheeses in the championship because of their breadth of experience.

Working in the industry can also lead to an invitation. They often have an area of expertise, like provolone or parmesan, and are asked to judge those categories.

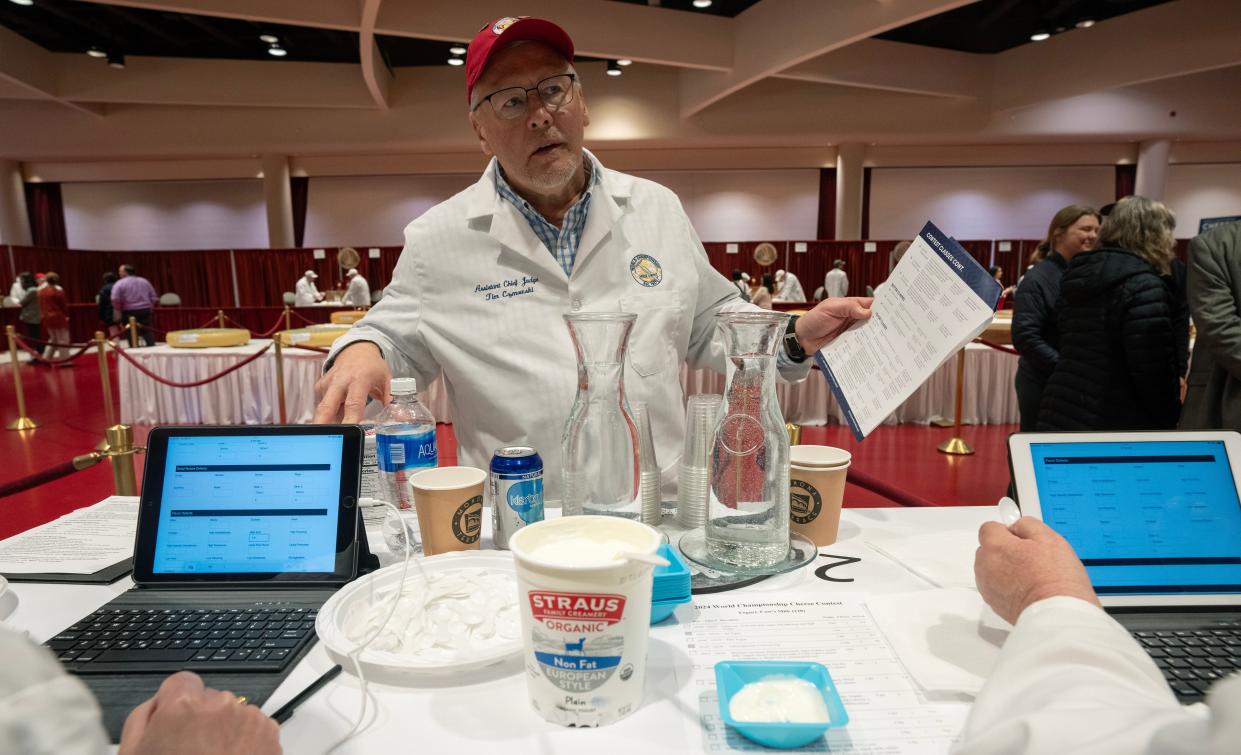

Tim Czmowski, one of the contest's several assistant chief judges, grew up on a South Dakota dairy farm and worked at several dairy companies, including Land O'Lakes. He's been judging since 1995. He's also become the contest's go-to person for cheese puns.

"Doesn't get any cheddar than this," he said a couple hours into the contest.

Always bring back-up triers

Cheese judging is serious business.

Sommer brings his briefcase to judging. It contains six cheese triers, which are T-shaped devices inserted into cheese, twisted and pulled to remove a log-shaped sample called a "plug." Triers allow cheesemakers to sample their work without cutting open the entire wheel.

For world championships, Sommer always brings extra triers in case the international judge he is paired with forgets to put their triers in their checked luggage.

"You’d never get a cheese trier through TSA," he said. "It could be considered a weapon. They’re very sharp."

25% of people could never land the job

Sommers and some other judges consider themselves to be "supertasters," which he said means they have more tastebuds on their tongues. Supertasters' sense of bitter is much stronger than other tasters', which is especially important when evaluating cheeses like cheddar.

About half of the world's population are average tasters, he said. A quarter are supertasters. The remaining 25% of people cannot taste bitter well and couldn't make it as a cheese judge, Sommer said.

Interested in learning the basics? The Center for Dairy Research offers a variety of cheese grading and cheese judging classes open to the public.

Not much eating involved

To preserve the their palates — and let's be honest, their digestive tracts — judges spit out the samples after a couple chews.

Palate cleansers between entries preserve judges' tastebuds. Some simply turn to water. Others opt for Sprite, saltine crackers or apple slices.

Jaeggi said Diet Pepsi works well for him. He'll turn to heavy cream to cut through the salt or heat of certain categories. Judging dozens of pepper-flavored cheese entries, for example, can be "brutal."

"My shirt was soaked through by the end," Czmowski said about his stint judging the high-heat pepper-flavored class.

The perfect cheese does not exist

Judges agree the hardest part of their job is picking winners. The quality in the world championship is so high.

Sommer said he judged Muenster one year when the "normal Muenster judge" couldn't make it.

"That was really tough because they were all so good and so close," he recalled. "In a class like that, where a whole mess of them within that class are just really top-notch, it's really tough to split those hairs and pick the tops of the group."

Each cheese starts with the score of 100. Judges hunt for "defects" to deduct points. The score sheet offers more than 50 ways to ding cheesemakers.

Cheese can be curdy-bodied (too rubbery), pasty (sticky) or gassy (too many holes). "Nesting" is when the "eyes," or holes, of a Swiss cheese are unevenly concentrated at the top or bottom of the block.

No cheese, not even the grand champion, walks away with 100 points. The 2022 winner, a Swiss gruyere by Michael Spycher of Mountain Dairy Fritzenhaus, scored 98.423.

"There's no such thing as a perfect piece of cheese," Czmowski said.

Judges struggle to name favorite cheese

Ask a judge to pick their favorite and most will clam up, dodge the question or offer a long, unranked list.

Susan Larson of UW's Center for Dairy Research said she leans toward juustoleipa, a Finish bread cheese, or gouda.

If Sommer had to pick, it'd be a two-year-old sharp cheddar. But he's got roughly 20 kinds of cheese in his fridges at home at any time.

"My wife gives me heck all the time about it," he said.

Lopez-Hernandez said he had a list of "about 50 cheeses" he enjoys.

"Gun to my head, if I absolutely had to pick one, oh gosh, it depends on the day," Jeaggi said. "I like Limburger, I won’t deny that. But you can’t pick your favorite child no more than you can pick your favorite cheese."

Judges feel enormous honor and privilege

This year's contest marked the public's return to the championship after COVID-19 restricted the 2022 contest to the most essential staff.

On Tuesday, the sample table swarmed with spectators. Cheesemakers offered demonstrations. Czmowski tried out some of his newest puns, which were often met with groans.

Romayn Rote, who has enjoyed attending the contest for nearly 20 years, was among the earliest visitors. He remembers running into Jaeggi, a childhood friend, the first time he made the trip.

"What's a Swiss boy from Green County doing here judging the world's best cheese?" he remembered asking Jaeggi.

"Lucky," Jaeggi said.

Contact Kelly Meyerhofer at kmeyerhofer@gannett.com or 414-223-5168. Follow her on X (Twitter) at @KellyMeyerhofer.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: World Championship Cheese Contest judges have hard job picking winner