Inside ‘Sidney’: Oprah’s Love Letter to Trailblazer Sidney Poitier

Plenty of movie stars, directors, historians and politicians (and certainly Oprah) have sung the praises of Sir Sidney Poitier. Not only was the Oscar-winning legend, who died at age 94 this past January, a deeply magnetic and charismatic performer; he was a radical symbol during Hollywood’s extremely white Golden Age and a rare, unifying force in a segregated country.

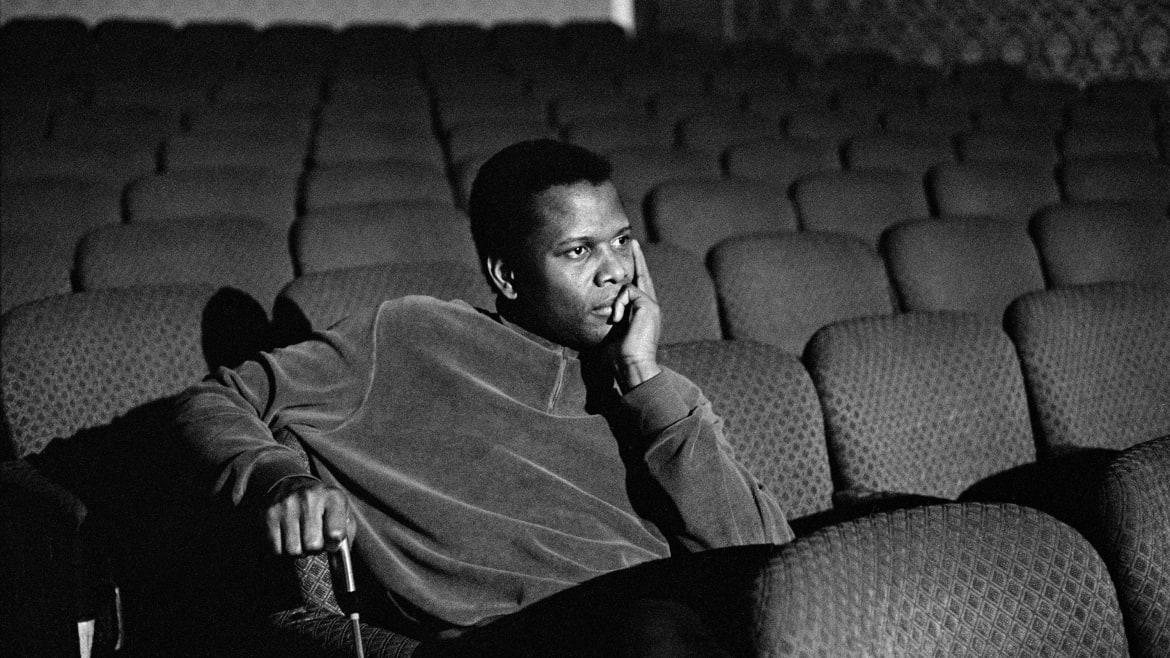

These testaments of Poitier’s magnitude as an artist and the effect he had on interracial audiences in the 1950s and ‘60s supply much of Sidney, a new documentary from Apple TV+ debuting at the Toronto International Film Festival and available to stream on September 23.

Directed by Reginald Hudlin (whose credits include House Party and Boomerang) and produced by Oprah Winfrey, the almost 2-hour film is a sweeping examination of the actor’s personal and professional lives and activism during the civil rights movement. Aside from an episode of PBS’ American Masters in 2000, the Lilies of the Field star has not been the subject of a major documentary film despite his seismic contributions to the visual medium. Sidney is a formal attempt to give the cultural icon his flowers and illuminate the weight he bore as a representative for Black Americans on screen.

Chelsea and Hillary Clinton’s ‘Gutsy’ Is a Toothless Girlboss Vanity Project

Sidney begins with a poignant story about Poitier’s almost ill-fated birth in Miami, Florida, in 1927. Born two months early to Bahamian tomato farmers, the actor tells us matter-of-factly via voice-over that he was “not meant to survive.” His father, Reginald Poitier, showed up to the home where his mother Evelyn was giving birth with a shoebox prepared to discard his body until Poitier miraculously pushed through. This anecdote, mentioned again later in the film, serves as a larger metaphor for Poitier’s surprising career trajectory during an extremely hostile time for Black Americans. It also comes to mind as we hear about the physical threats he encountered from the police and the Ku Klux Klan after moving to the United States from the Bahamas at 15.

The rest of Sidney moves in chronological order, from Poitier adjusting to America’s oppressive racial climate as an immigrant from a predominantly Black island to his turn as a producer and director in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Poitier is the documentary’s primary narrator and talking head at the start of the film and toward the end. Presumably, he wasn’t able to partake in portions where his absence is rather noticeable. Still, where Poitier is present, the documentary benefits from his commanding demeanor and captivating tone as he guides us through the most profound moments in his life.

The documentary gives viewers a pretty solid overview of Poitier’s career once he emerged from the theater scene and broke into Hollywood. Actors like Morgan Freeman, Halle Berry and Denzel Washington speak about the significance of watching him in No Way Out, The Defiant Ones, A Raisin in the Sun, In the Heat of the Night and Lilies of the Field, while critics Nelson George and the late Greg Tate provide some historical context for these characters. Of course, the film wrestles with the passé political messaging and didactic nature of some of Poitier’s most iconic roles, like in Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, and the accusation by certain Black moviegoers that he was fulfilling a liberal white fantasy of a “respectable” Black man.

It is here that Sidney inadvertently makes the argument for a completely separate documentary focused solely on the contradiction of Poitier as both a revolutionary and conservative symbol of Blackness during the civil rights and Black Power movements. You could also dedicate an entire film to his decades-spanning friendship with Harry Belafonte, who he apparently fought with like “a married couple.” We get brief glimpses of their unique brotherhood as each other’s main comrades—and competition—in Hollywood and partners in civil rights activism. In the second half of the film, there’s a brief mention of a tense argument between the two after Belafonte suggested they hold a rally to honor Martin Luther King Jr.’s death that Poitier believed was in bad taste. The two wouldn’t speak again until they worked on the 1972 Western film Buck and the Preacher. Seeing the aged actors reignite their friendship on set is one of the most touching parts of the film.

Overall, Sidney is a pretty paint-by-numbers biographical film with little to no experimentation visually or narratively. However, it still manages to captivate given the complex man and subject matter at its center. The documentary does what it sets out to do, which is to provide a definitive overview of Poitier’s monumental legacy, and will certainly make audiences more curious about lesser-discussed aspects of Poitier’s gigantic career, like his more idiosyncratic turn directing comedy films. Hopefully, Hollywood will allow more opportunities to unpack his deeply fascinating life.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.