Inside the 1994 Penske PC-23, the Car that Dominated IndyCar's Golden Era

It’s hard to fathom now, but in 1994, IndyCar racing was the country’s most popular form of motorsport. The series, sanctioned by CART, was increasingly global in its aspirations. The ’94 grid included three former Formula 1 champions and one future F1 champ. Chassis maker Reynard entered the series to take on Lola and Penske. A new Honda engine debuted to do battle with Ford and Ilmor.

This story originally appeared in Volume 18 of Road & Track.

But for all its mechanical diversity, 1994 was Penske’s year. A murderers’ row of drivers—Emerson Fittipaldi, Paul Tracy, and Al Unser Jr.—piloted Penske’s three Marlboro-sponsored entries. Of the 48 total possible podium positions that season, Penske drivers took 30. The Penske trio managed five podium sweeps. Unser won the drivers’ championship and the Indy 500. Penske won the constructors’ title, and the team’s engine builder, Ilmor, took the manufacturers’.

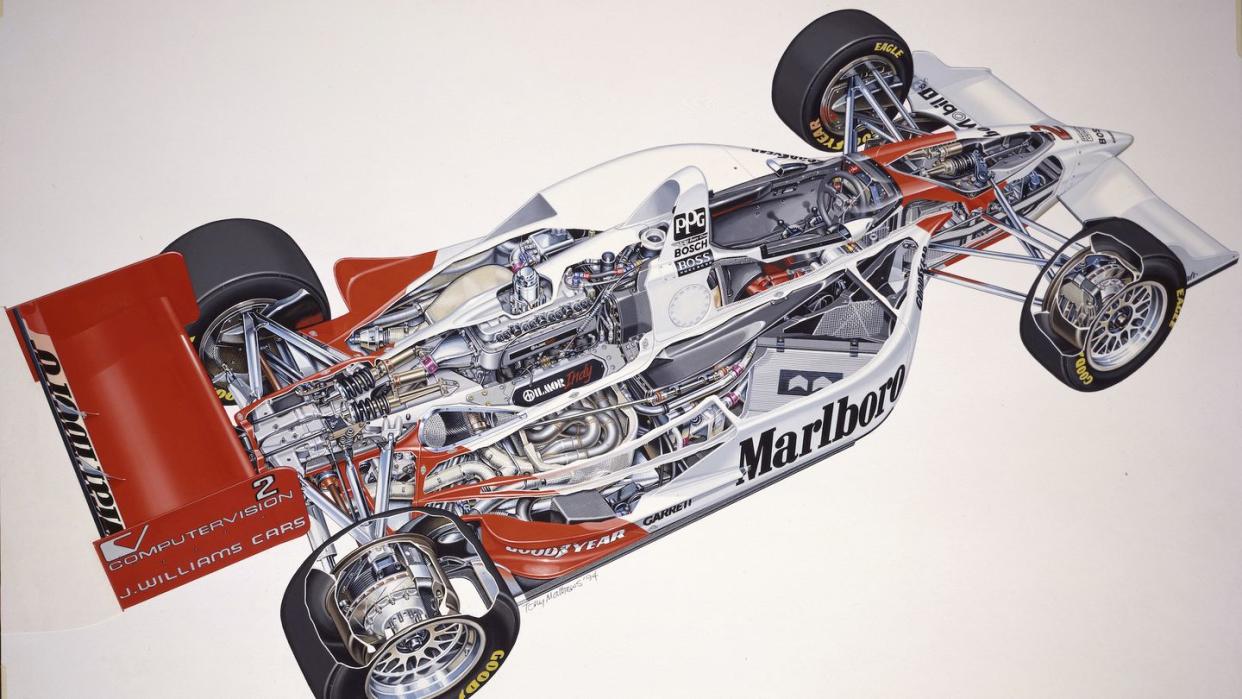

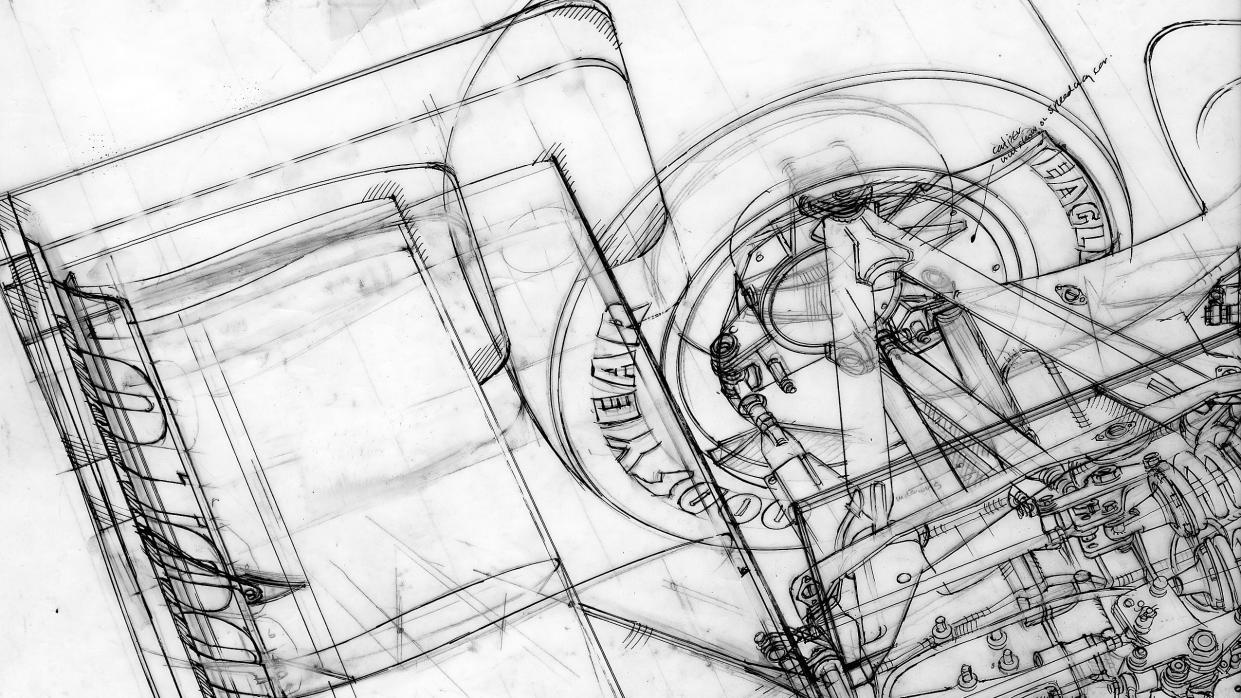

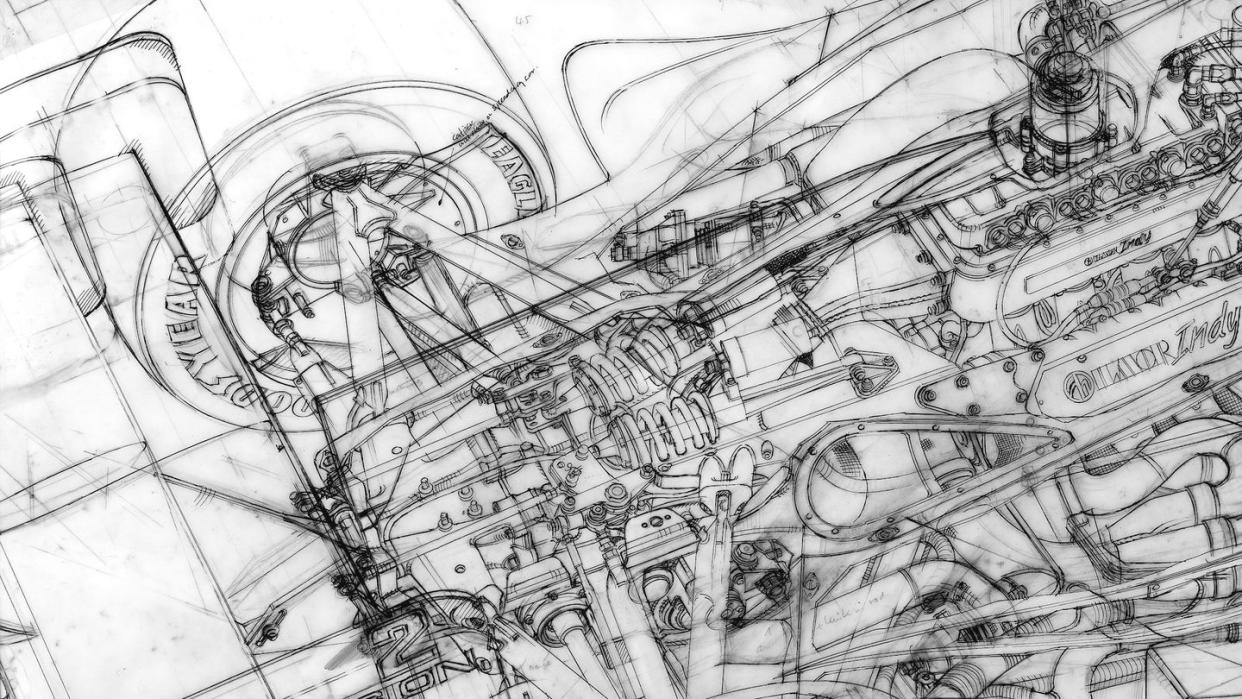

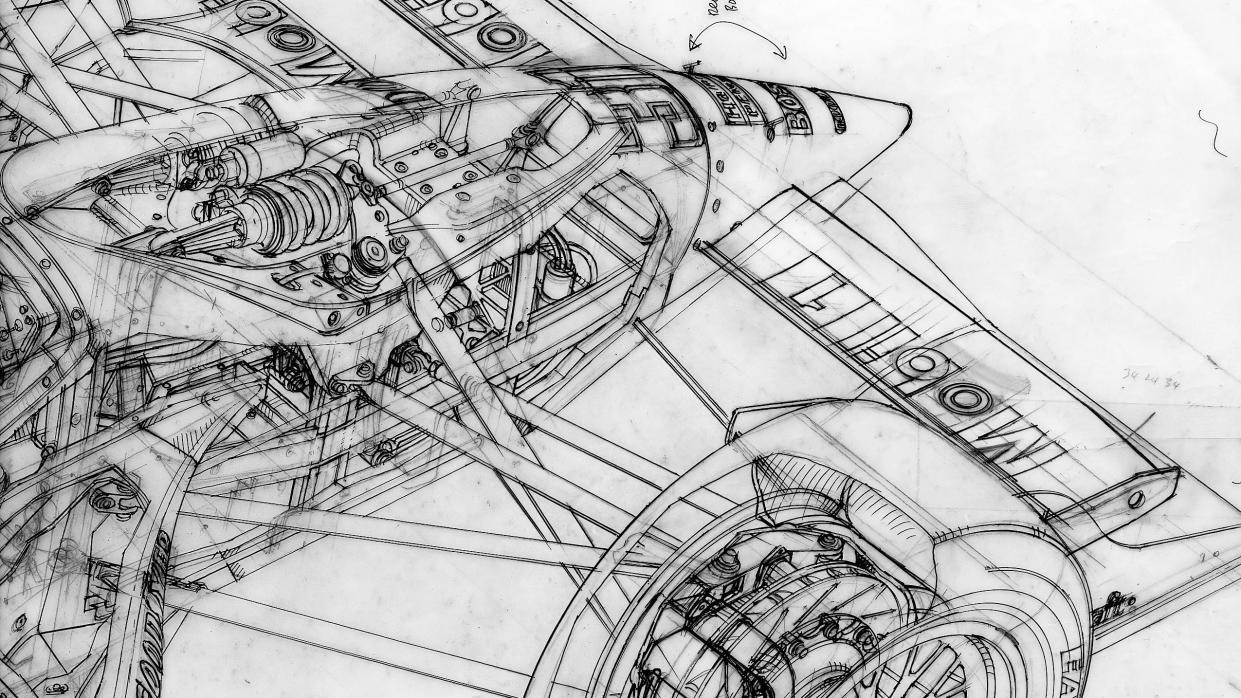

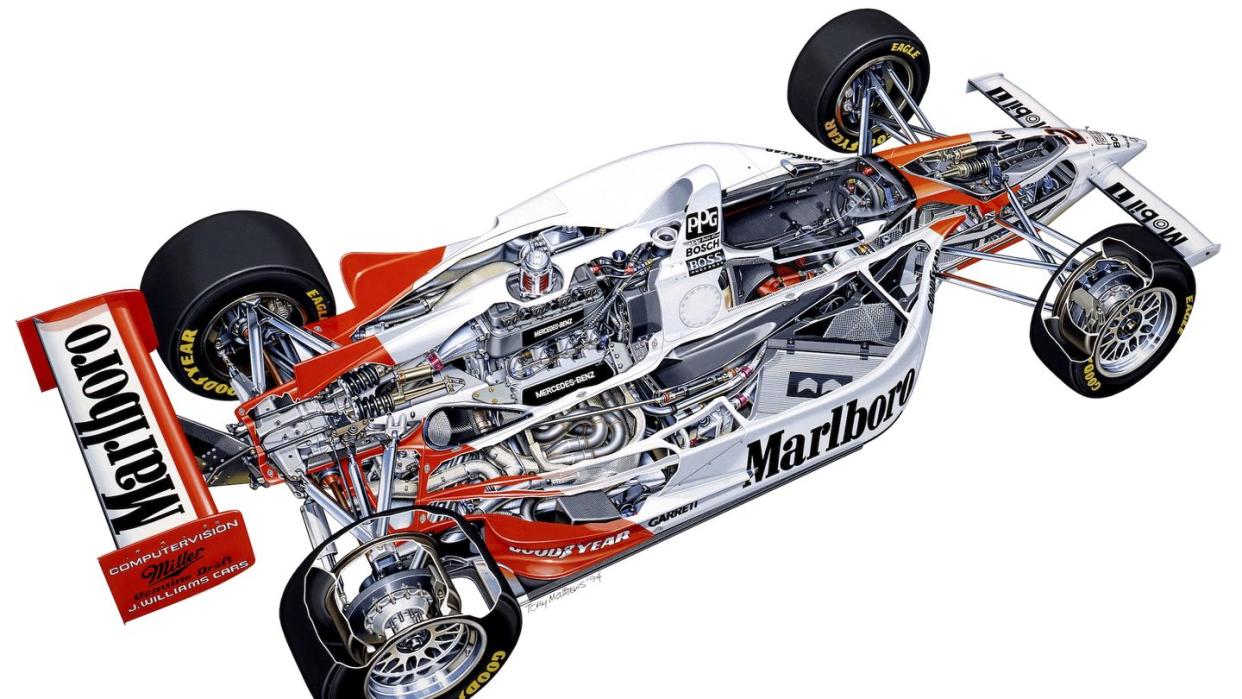

There to capture the Penske cars and their engines in minute and exquisite detail was Tony Matthews, among the best cutaway illustration artists ever to put pencil to paper. The illustrations you see on these pages are all his.

In the following years, IndyCar would all but destroy itself, splitting into two warring factions. But those were just dark clouds on the horizon of a sun-drenched sky in 1994.

Heave Ho

Short of the 1988 McLaren MP4/4, it’s hard to imagine a more dominant topflight open-wheel race car than the Penske PC-23. What makes this car, which won 75 percent of the races in 1994, all the more compelling is that it was little more than an evolution of the PC-22, which won half of the previous year’s races.

The PC-23’s construction wasn’t revolutionary: a carbon and aluminum honeycomb tub with a single-turbo 2.65-liter DOHC V-8 bolted to the back and the transmission secured to the tail end of the engine. Its body was carbon fiber. It rode on a pushrod-activated suspension, with steel control arms (the mandated material) polished

to a high sheen.

Matthews drew both road-course (previous page) and speedway (following pages) versions, and in sketches, he put both aero packages on the same car. What you can’t see in the image are the so-called third springs (or heave springs) front and rear. The third springs dealt with the car’s enormous aero downforce and kept the chassis parallel to the ground under braking and acceleration, allowing the team to run a lower ride height. Penske Racing was, after all, a client of Matthews’s, and

no team wants its secrets revealed.

Unfair Advantage

If you’ve heard of the Mercedes pushrod engine that powered Unser’s Penske to his Indy 500 win, you’ll no doubt have heard that it’s a cheater or loophole engine that was outlawed after one race. That’s not technically true. This Ilmor-designed and Mercedes-badged engine, a 3.4-liter V-8 with a single turbo

and a pushrod-activated valvetrain, was perfectly legal. Clause 115-D of the USAC Indy 500 rulebook once required that pushrod engines be based on stock production blocks. If you ran a stock block, USAC would allow you to run more turbo boost than the dedicated racing engines of competitors.

But stock-block engines proved disastrously unreliable at Indy. Now a company could get the advantage of the extra turbo boost by building a designed-from-scratch racing engine, as long as it was a pushrod motor. But it would be usable only at Indy, and the cost and effort would be enormous. The idea was too enticing for Penske and Ilmor to pass up, resulting in a new pushrod engine, the 265E. The new engine needed to be precisely the same length as the regular-season motor so the team could use the same chassis. Like the team, Matthews had to swap the new engine into his drawing (right). It would eventually make more than 1000 hp and an absurd amount of torque, blow the dyno-room door open, regularly receive parts flown across the Atlantic on the Concorde, spin the rear wheels within the tires, and win one race. Not only did Unser win, but another Penske driver, Fittipaldi, led most of the race. In all, the Penskes took 24 of the 25 fastest laps of the 1994 Indy 500.

After such a surprise drubbing, Penske’s monster motor had its maximum turbo boost legislated down from 27 psi to 25.5. The adjustment was small, still allowing the engine to make very competitive power.

It wasn’t until Tony George, who controlled the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, announced the creation of a rival series, the Indy Racing League, that Penske’s engine was cut to 23.6 psi of boost, rendering it uncompetitive.

You Might Also Like