Idea exchange or corporate lobbying front? A look into ALEC’s influence in NC

As state budget negotiations stagger into August, a group of North Carolina lawmakers were ensconced last week at an Orlando resort that boasts a lazy river, water slides, restful lagoons, luxury cabanas and an 18-hole golf course.

The lawmakers attended the 50th annual meeting of the American Legislative Exchange Council, which advertises itself as “America’s largest nonpartisan organization of state legislators dedicated to the principles of limited government, free markets and federalism.” At the JW Marriott Orlando, Grande Lakes, they took part in discussions about state policy with legislators from across the country, as well as representatives of corporate and industry interests.

The politically conservative organization regularly convenes state legislators from around the U.S., mostly Republicans, with private sector representatives to write and publish “model bills,” draft legislation that can then be used by anyone.

For example, if a state lawmaker has a policy goal in mind, like wanting to expand charter schools, they can pull a model bill from ALEC, customize it and introduce it into their legislature. ALEC has faced criticism for using a “bill mill” formula to push a national agenda down to the states.

“What I worry about in the general sense is you want to think that proposals and legislation comes from the people who are electing the folks representing them in the legislature and that there is some kind of local initiative for that,” said Bob Phillips, executive director of Common Cause NC. “But when you have a bill mill that really is serving the interests of special interests in corporate America and right-of-center agendas, that’s alarming.”

Conservatives contend that ALEC is just another player in the vast field of influences on state policy.

“The idea of suggesting draft legislation is not new. It didn’t start with ALEC,” said John Hood, president of the conservative John William Pope Foundation. “Lots and lots of organizations, left, right and center, do that all the time.”

State Rep. Ray Pickett, a newer ALEC member who has attended two of its conferences, emphasized that the primary function is “collaboration with other states.”

“Talking to other people, that’s what the whole thing is. Meeting people and having contacts outside of your home state,” he said.

How does ALEC work?

There are two primary ALEC memberships: legislative and private sector. Legislative members like Pickett must be elected officials, and pay a $200 two-year membership fee. Costs incurred from attending conferences can eventually get reimbursed by ALEC, according to Pickett.

Private sector members, which includes corporations and private foundations, pay membership fees that range from $5,000 to $25,000. ALEC boasts of nearly 300 private sector members.

Members are divided into task forces that hold online meetings throughout the year to discuss model legislation proposals. According to Pickett — who is a member of the energy, environment and agriculture task force — 50 to 70 proposals are made each year. About four are chosen to be discussed further.

The task forces then meet in-person at the annual conferences, where the chosen proposals are voted on. Within each task force, there is a fifty-fifty split between legislative members and private sector members, who all get a vote. If passed, the model legislation moves to the ALEC Board of Directors, which decides whether to give the model legislation official ALEC endorsement. The board consists of current state lawmakers. There is also a Private Enterprise Advisory Council consisting of corporate and industry representatives that do not vote on model legislation.

“It’s like any other conference. Doctors, they have conferences, and they talk about new technology,” Pickett said. “But we talk about new policy, and that’s what we discuss pretty much all day long.”

Impact on NC legislation

Around 40 of North Carolina’s 170 lawmakers are members of ALEC, which claims to include “nearly one-quarter of the country’s state legislators and stakeholders.”

Historically, some North Carolina policies have gone on to form the building blocks for ALEC model legislation. Several of the state’s lawmakers have served in top ALEC leadership positions. Former House Speaker Harold Brubaker and state Rep. Jason Saine served as ALEC national chairman in 1994 and 2018, respectively. Saine, a Lincoln County Republican, sits on its Board of Directors and serves as ALEC state chair, along with state Reps. Dennis Riddell and Kyle Hall. Sen. Thom Tillis, state Sen. Timothy Moffitt and former state Rep. Fred Steen have also spent time on ALEC’s Board of Directors.

ALEC’s influence on North Carolina legislation is not always so direct. Nonetheless, The News & Observer was able to identify multiple recent bills that bear similarities to ALEC model bills, with some even borrowing exact language.

Here are a few ALEC-inspired bills that saw action during this legislative session:

House Bill 750: This law prevents state pension plans from considering environmental, social and governance factors. A veto of the bill was overridden by Republicans in June. Certain provisions are taken directly from ALEC’s State Government Employee Retirement Protection Act, and similar laws have popped up in over a dozen states.

House Joint Resolution 235: The resolution would have NC join a handful of other states in formally applying for a constitutional convention. Two-thirds of the states would need to call for such a convention, which would allow states to propose amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It passed the House in March, but has not been acted on in the Senate. Most of its wording is taken from a counterpart ALEC bill.

Senate Bill 364/House Bill 187: Both bills would limit the discussion of certain topics in the workplace and in public schools. Only SB 364 was passed into law, after a veto was overridden in June. HB 187 passed the House in March. The bills share bits of language and similar overall goals to ALEC’s Honesty in Teaching Act, as all aim to stifle discussion on topics related to race and sex.

Senate Bill 49, Parents’ Bill of Rights: The bill was recently vetoed, but contains a provision that would require schools to make classroom materials available for parental review at the schools and online. The provisions resemble ALEC’s Academic Transparency Act, which would impose similar requirements.

ALEC has also had a major influence on important legislation in the past few years, according to Senate Democratic Leader Dan Blue’s office:

2011 House Bill 650, Castle Doctrine: This controversial law allowed property owners to legally use deadly force on intruders with no obligation to retreat. Large parts of the law are taken straight from ALEC’s now-retracted Castle Doctrine Act, which was based on Florida’s 2005 “Stand Your Ground” law. After the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2012, ALEC’s support for the law came under scrutiny, leading to nearly 400 legislators and 60 corporations cutting their ties with the organization. ALEC later announced that it was “refocusing” on promoting business and economic laws, and shying away from cultural issues.

2013 House Bill 589, Voter ID: This voter ID law was eventually struck down by a court for its “discriminatory intent,” and drew influence from ALEC’s Voter ID Act.

2015 House Bill 1080, Achievement School District: The law created an “innovative school district” that eventually ended in 2021 due to a variety of issues. It was likely inspired by ALEC’s Innovation Schools and School Districts Act. At the time, the Education Freedom Alliance, which has ties to ALEC, spent thousands of dollars to purchase a full-page ad in The News & Observer to urge passage of the bill.

Parts of 2021 state budget: An emergency power limitations law included in the budget limited the governor’s emergency powers and went into effect at the start of 2023. It drew influence from ALEC’s Emergency Power Limitation Act. Both were a response to emergency declarations by state governors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hudson McCormick, the North Carolina state director for the State Innovation Exchange (SiX), which is often seen as a progressive counterpart to ALEC, said the nature of ALEC’s influence has changed in the past couple years, especially after the public’s reaction to the Castle Doctrine in 2012.

“One of the more interesting questions to ask now, at this stage in ALEC’s development, is not necessarily what are they actively dipping their fingers in? But how is their model spreading across the far-right infrastructure?” he said.

McCormick argues that ALEC’s model of preparing copy-and-paste legislation is being used by far-right groups like the Election Integrity Network or Moms for Liberty to push cultural issues onto the states.

Saine disputed such a characterization of ALEC.

“I think the bigger influence is that it’s a place for like-minded conservatives that appreciate smaller government and individual liberty and freedom to coalesce around and to share ideas,” he said.

Saine points to organizations like the National Conference of State Legislators and the Council of State Governments, saying that ALEC “somehow becomes the boogeyman.” He argued that NCSL provides a nearly identical experience to ALEC for Democrats, and is funded partly by state tax dollars, which ALEC is not.

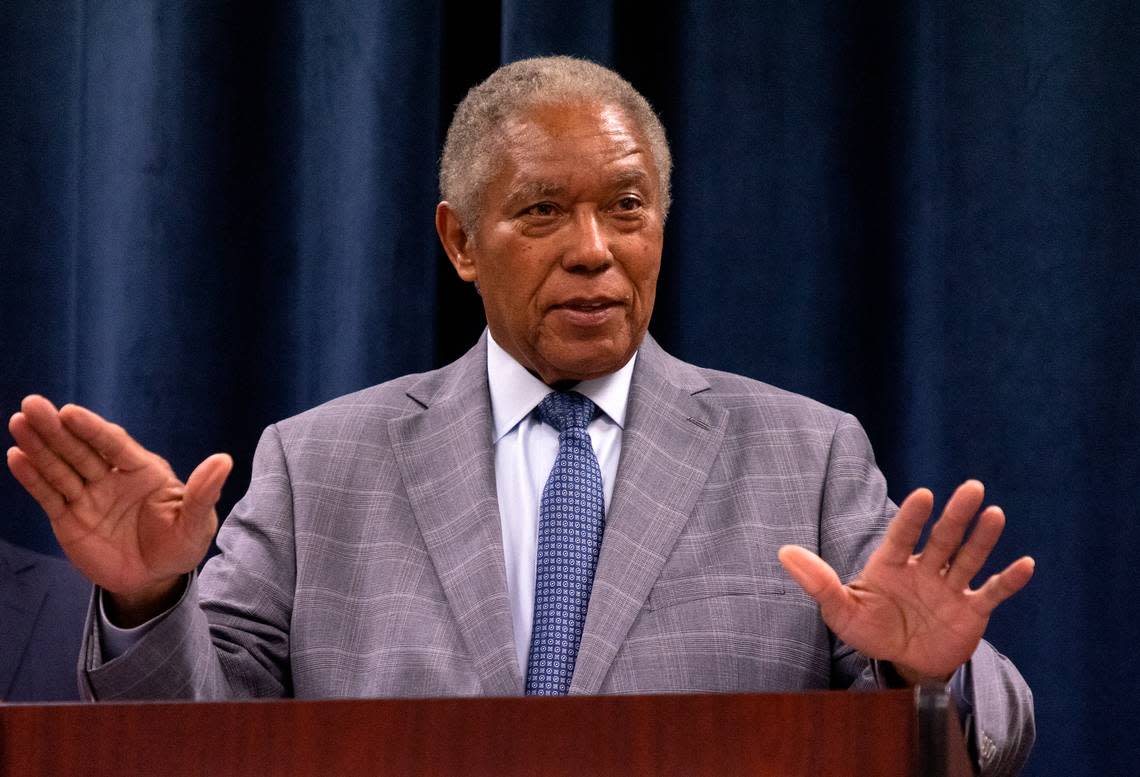

Blue, a two-time president of NCSL, disagreed. He noted that NCSL is bipartisan, with both Democrats and Republicans in leadership, and that the makeup of the organization’s membership looks different.

“They’re totally different. You don’t just have the corporate lobbyists, you have a broader group of advocates out there,” he said. “It’s a broad range of advocates, interests and people that the elected officials, the legislators, interact with at an NCSL convention.”

Debate on corporate ties

ALEC’s financial and membership structure means that less than 1% of its revenue comes from legislator membership fees, according to Lisa Graves, executive director of the Center for Media and Democracy. Some of its biggest donors from 2014-19 include the Bradley Foundation, Charles Koch Foundation and Searle Freedom Trust, according to the CMD.

Hundreds of corporations also help fund ALEC, though their identities are not publicly disclosed. This has led to scathing criticism of the organization in the past few years, with many accusing ALEC of being a “pay-to-play” corporate lobbying front.

“Unlike the legislators who are the temporary leaders of ALEC, the real longtime leaders of ALEC are these corporate lobbyists,” Graves said. “When you see the bills moving in North Carolina and other states, what you’re seeing is an agenda, that’s really a national agenda, that is largely supported by the big funders of ALEC to change people’s rights in numerous ways and limit corporate accountability.”

But Pickett said the contacts he has made with corporate representatives at ALEC meetings have helped him serve his constituents better, especially on more technical topics in which he lacks expertise, like telecommunications.

“They’re a great source of knowledge. There’s no way we can know everything of these bills that come through this building,” he said. “I’ve not had a single person that I felt gave me any misguided information — they gave me the truth. Whether it was good for them or not, they at least gave me the truth of the questions I asked.”

Pickett also argued that, unlike the actual lobbyists that roam the halls of the Legislative Office Building, he’s never had lobbyists at an ALEC conference attempt to push any proposal onto him.

Regardless, those passive relationships built between corporate representatives and state legislators are still problematic, according to Jane Pinsky, director of the NC Coalition for Lobbying and Government Reform.

“There’s no problem with them talking to and listening to a corporate lobbyist. When they start to wine and dine people, which they do, I believe that ALEC kind of crosses the line,” she said. “I think among North Carolinians, it can create a perception of money influencing the process, and that is the last thing we need right now.”

Graves is more direct.

“(These are) lobbyists who are in a private room at a hotel, sitting around voting on those bills with them. For a lawmaker to assert that they don’t feel any pressure in that environment, is astonishing to me. It reads like fiction,” she said.

All of ALEC’s “model policies” are posted on its website, including drafts that have yet to be approved by the Board of Directors. They were only made publicly available, however, after Graves’ Center for Media and Democracy published the bills brought to them by a whistleblower. Graves also noted that reporters aren’t allowed in most task force meetings where the bills are voted on.

“It still has to go through the whole committee process, it still has to go through the scrutiny of the press, the public and everyone else looking at it, and deciding whether or not the legislation is something that can get a majority of the votes,” Saine said. “People talking to each other, I think it’s a good thing; and exploring ideas, I think it’s a good thing.”