Idaho parole board mulls clemency for longest-serving death row prisoner in pivotal hearing

Idaho’s parole board tasked itself Friday with making a pivotal choice during a clemency hearing for Thomas Creech, the state’s longest-serving death row prisoner: Does a man convicted of five murders across three states — including three in Idaho — who claims immense remorse after nearly 50 years of incarceration deserve to be spared from execution?

The Commission of Pardons and Parole’s decision may come down to which of two distinct narratives they believe from the portraits painted by each side about the 73-year-old Creech. Is he the contemplative and contrite friend and mentor following decades in prison that his defense presented, or the manipulative charmer who used to claim he killed dozens of people with reckless abandon, even after he was incarcerated, as prosecutors asserted?

The parole board immediately went into executive session at the end of the public portion of the hearing, though it wasn’t clear if they would cast their votes Friday on whether to grant his request to reduce his sentence to life in prison. Their ruling will be posted at a yet to be determined date, a spokesperson told the Idaho Statesman.

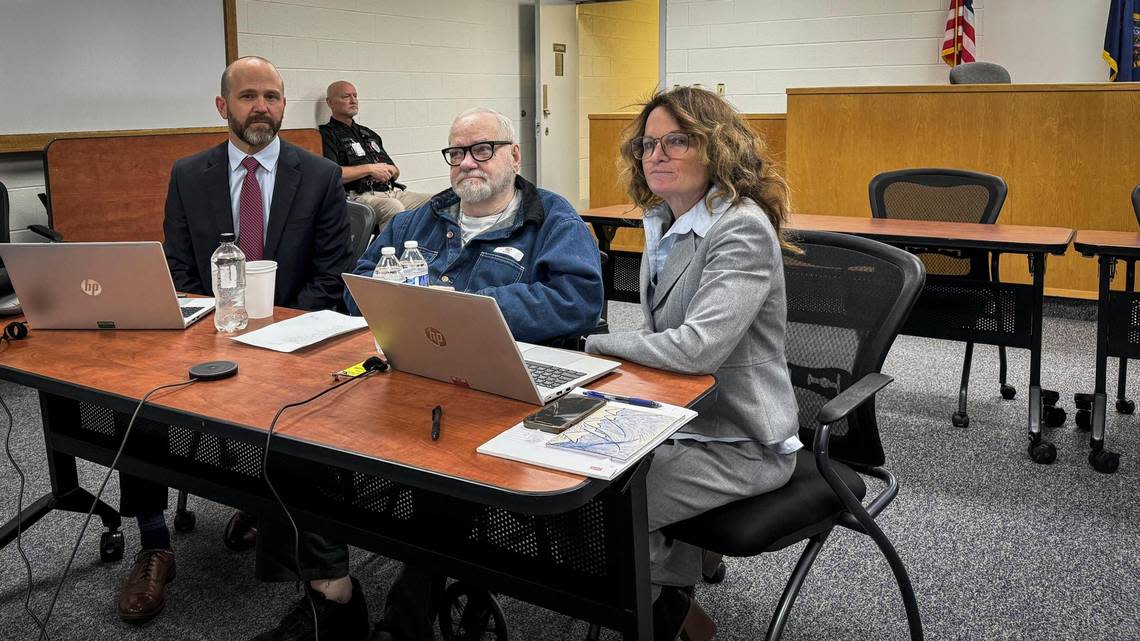

Prosecutors and his defense team traded volleys during the all-day — at times sobering and tearful — hearing with yet another person’s life on the line: Creech’s. Photos from Creech’s childhood and smiling with his family ran counter to grisly images of the body of his most recent victim, a fellow prisoner who he bludgeoned to death at the maximum security prison in 1981.

“That’s his language, the language of violence,” said Ada County deputy prosecutor Jill Longhurst, labeling him a “sociopath.”

But in Creech’s corner was a diverse group of advocates who spoke up on his behalf, which halted the state’s latest attempt to execute him when the parole board agreed in October to the rare hearing to consider reducing a death row prisoner’s sentence. Commissioner Mike Matthews, who led the meeting, acknowledged Creech was “very fortunate” to receive the hearing at all — just the third of its kind in Idaho for a death row prisoner since capital punishment was reestablished in the state following a 1976 U.S. Supreme Court ruling.

Creech’s list of supporters came from unlikely places, including several former state prison workers — two of whom showed up to offer in-person testimony — one current corrections officer who also showed up Friday, a former state representative and even the Ada County judge who handed him the death penalty for beating and stomping to death prisoner David Dale Jensen in 1981.

“I’m here to request that he be allowed to spend the rest of his life in prison,” testified Gary Hartgrove, a retired deputy warden at Idaho’s maximum security prison, which houses death row. “Mr. Creech is old, in poor health, a low security threat, and the prison staff will suffer if he is executed.”

Creech’s total murder victims unclear

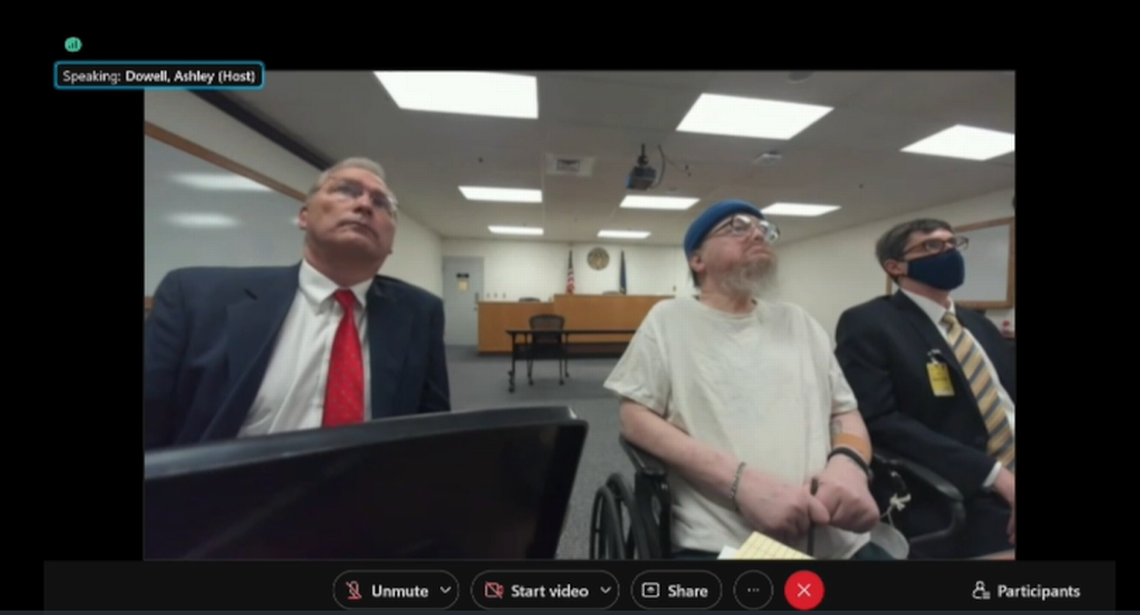

Creech sat forward, hands folded in a wheelchair for much of the hearing before the the parole board, appearing by video from the courthouse at the maximum security prison south of Boise. At points he wiped his damp eyes from behind black-rimmed glasses when supporters praised him, and also sunk his head into one of his hands when descriptions and photos of Jensen’s murder were presented by the state.

Creech has changed and is a genuinely kindhearted person whose life is worth saving, his wife of 25 years, LeAnn Creech said in recorded video testimony played at the hearing. They married in 1998 after the two were introduced by her son, a prison guard at the time.

“I just think that he’s actually the person that he was meant to be to begin with,” LeAnn Creech said.

Today, Thomas Creech is a mostly quiet, docile man and not the murderous myth he’s been made out to be for decades, Creech’s attorneys with the nonprofit Federal Defender Services of Idaho said. Through his documented good behavior over nearly 30 years, he has earned the chance to continue his redemption story, they said.

“I regret everything that I’ve ever done wrong,” Creech told the parole board, specifically citing Jensen’s murder, for which he remains on death row. “The person I am now is not the person I was then. Maybe the person I used to be didn’t deserve mercy at all. But I think I have a lot to offer to people.”

The prosecution, meanwhile, focused their talking points for maintaining Creech’s death sentence on his long history as a killer who they said indiscriminately took the lives of others. His many victims’ lives were cut short at his hands, their dreams unrealized and stories left untold, Longhurst said.

Besides Jensen’s murder, which she said Creech has never told the truth about in claiming it was self-defense, Creech was convicted of four other murders — two men in Valley County in November 1974, plus a man in Northern California and another in Oregon, each also in 1974. The prosecution also linked Creech to at least six other murders, including the stabbing death of a 70-year-old man in Arizona in 1973, all the while still bragging for years about others, Longhurst said.

“That’s not a myth, this is reality. He is a serial killer,” she said. “These are real people, and they had lives.”

Creech was acquitted by a jury of the Arizona murder, noted Chris Sanchez, one of Creech’s attorneys. Pressed later by Matthews and Commissioner Scott Smith on the number of people he had actually killed, Creech was noncommittal on a number beyond his five murder convictions.

“I don’t really know for sure, I got so mixed up with lying and telling law enforcement things that I didn’t do,” Creech said. “When I was starting to kill people it was in 1974, and it was just within a matter of months when I did everything that I did.”

Creech had no fewer than 11 murder victims, including Jensen, and his death sentence should remain in place, Longhurst said. Since his conviction for the murders of Edward Thomas Arnold, 34, and John Wayne Bradford, 40, in Valley County, for which he initially received the death penalty, Creech has avoided execution 11 times.

Members of Jensen’s family, including his daughter, younger sister and two nieces who never met their uncle, gave victims’ statements Friday. Only one announced her name, while another said the family feared retaliation for speaking out against Creech on behalf of their deceased loved one.

Jensen, 23, of Pocatello, was mentally and physically disabled before he entered prison, including impaired speech and limited use of his right side, prosecutors said. He was also completely blind in his left eye and characterized as a low-profile prisoner who was non-aggressive, they said.

Each of Jensen’s surviving family at the hearing said for nearly 43 years, the wound of his death is torn open anew each time they have to relive the horrors inflicted upon them by Creech. Jensen’s murder has caused generational torment and heartache, they said, and they asked that the parole board finally allow justice to be served in their brother, uncle and father’s name.

Clemency decision forthcoming

A majority vote is needed among the seven-member parole board in favor of granting Creech the reduced sentence to remove the death penalty from his conviction for murdering Jensen. That recommendation then funnels up to Gov. Brad Little, who has the authority of final say on clemency decisions.

Six of the parole board’s commissioners were present Friday to take up Creech’s case. Commissioner Patrick McDonald recused himself from the meeting, Ashley Dowell, the parole board’s executive director, told the Statesman by email. Dowell declined to comment on McDonald’s potential conflict of interest.

McDonald is a former state representative and 41-year member of law enforcement, including 33 years with the Idaho State Police. Little appointed McDonald to the parole board in 2021 and also recently reappointed him, Dowell said.

McDonald’s absence from the hearing sets up the potential for a 3-3 vote on Creech’s clemency request. If the parole board votes in a tie, Creech’s request would be denied, Dowell said.

The parole board held two previous clemency hearings for death row prisoners since 1976 — the same year Creech was first sentenced to death for the Valley County murders.

In 1996, the parole board voted 3-2 to grant a life sentence to prisoner Donald Paradis based on questions of his innocence, and then-Gov. Phil Batt accepted the recommendation. Paradis was later released from prison in 2001.

And in 2021, the parole board voted 4-3 to grant a life sentence without parole to prisoner Gerald Pizzuto, given his declining health after 35 years of incarceration. Little immediately rejected the recommendation and Pizzuto, now 68, was returned to death row, where he remains today.