As hundreds are missing in deadly Greek shipwreck – what are the deadly routes across the Mediterranean?

The sinking of a migrant boat off the coast of Greece has left at least 78 people dead – with the central Mediterranean facing one of its worst disasters in recent memory.

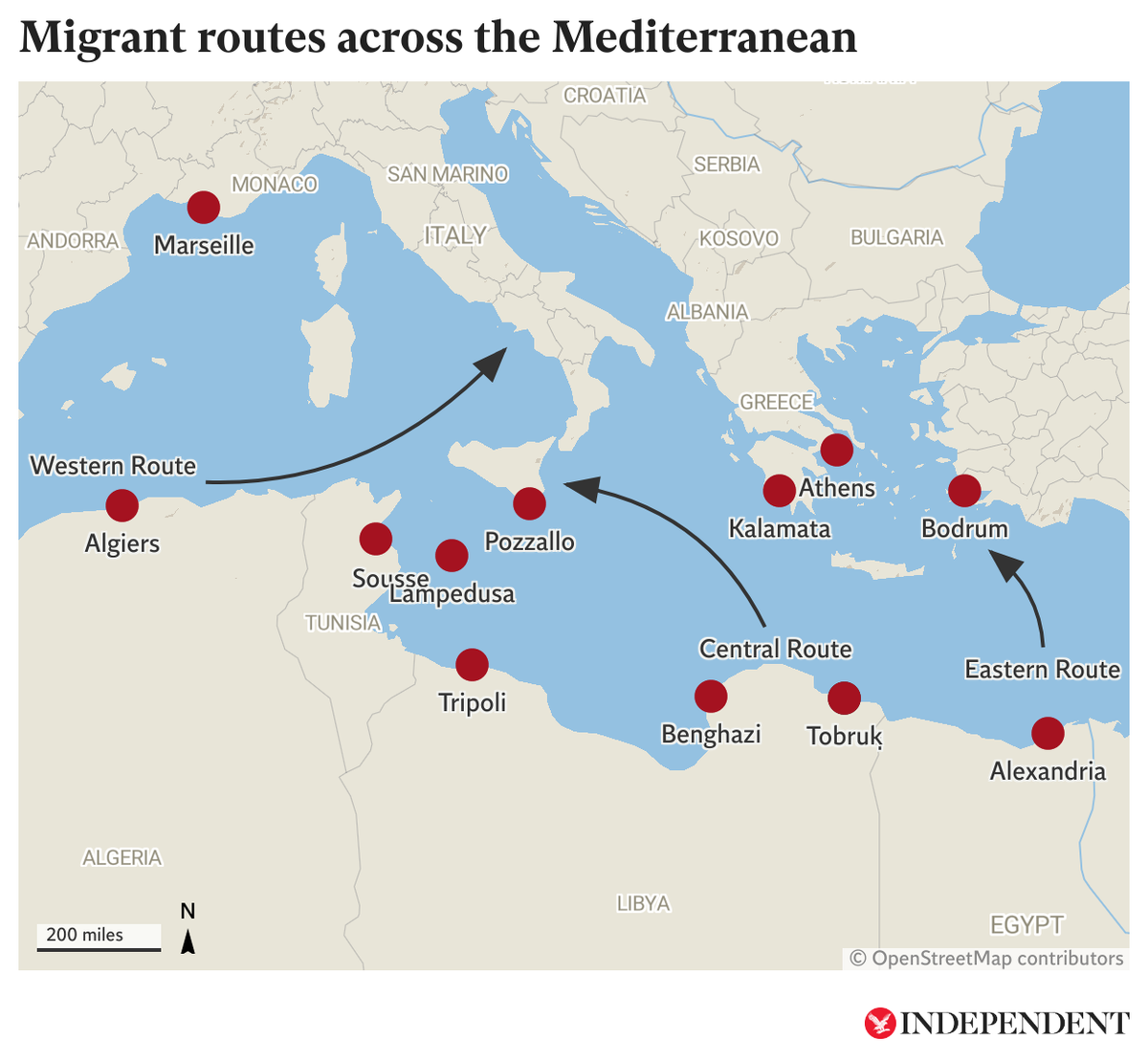

More than a hundred passengers have since been rescued from the stricken vessel, which was making the perilous crossing from Tobruk in northern Libya to southern Italy when its engine cut out, causing it to take on water and flood over one of the sea’s deepest points.

The craft, measuring 25 to 30 metres long, reportedly rebuffed offers of help from the Greek coastguard before it capsized and may have been grossly overcrowded with “more than 500 people” on board, according to Ioannis Zafiropoulos, deputy mayor of the southern port city of Kalamata, where the survivors were taken.

Those rescued so far include Egyptians, Syrians, Pakistanis, Afghans and Palestinians, all of whom were seeking escape from North Africa and the Middle East in search of a better quality of life in Europe.

The trip from North Africa through the central Mediterranean to southern Europe is the deadliest migratory route in the world, according to the United Nations’ International Organisation of Migration (IOM).

There are two other routes migrants commonly pursue across the same sea: the shorter crossing from the west from Morocco or Algeria into southern Spain or France or across to central Italy and the eastern route, often used in the past by people fleeing the likes of Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan into Turkey or Greece.

Many migrants prefer to attempt to bypass Greece and reach Italy, where they can more easily continue their journeys north to family and other migrant communities elsewhere.

Had the migrants aboard the sunken boat managed to land in Greece, they would have had to trek through the often-hostile Balkans to reach western or northern Europe, whereas the route north from Italy is closer and often more accessible.

Those migrants who do arrive in Greece typically cross from Turkey, either reaching its nearby eastern islands in small boats or by crossing the Evros river, which runs along the land border.

Crossings have fallen sharply in recent years, however, as Greece has stepped up its sea patrols and built a border fence along the Evros, although it has nevertheless faced persistent accusations from migrants themselves, human rights groups and from Turkish officials that it returns migrants back across the border to Turkey, illegally preventing them from claiming asylum, an allegation Athens denies.

Before this week’s disaster, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) had recorded 72,778 migrant arrivals in Europe via the Mediterranean so far in 2023, with the vast majority of that total, 71,136, arriving by sea with the aid of people smugglers.

Italy has recorded the vast majority of the arrivals to Europe so far this year, with 55,160, which is more than double the 21,884 who arrived in the same period in 2022 and 16,737 in 2021. People from Ivory Coast, Egypt, Guinea, Pakistan and Bangladesh account for the majority, according to Interior Ministry data.

The UNHCR has meanwhile recorded 1,037 people as dead or missing during that time in what was the deadliest first quarter in six years, giving an idea of just how dangerous the undertaking is and just how much risk migrants take on in attempting the crossing.

The IOM has recorded more than 27,000 deaths and disappearances in the Mediterranean since 2014.

The sea’s deadliest known shipwreck occurred on 18 April 2015 when an overcrowded fishing boat collided off Libya with a freighter that was trying to come to its rescue. Only 28 people survived. Forensic experts who worked to identify the dead concluded in 2018 that there were originally 1,100 on board.

That year one million refugees and migrants fled to Europe by sea, according to figures from the UN Refugee Agency. Some 1,000,573 people had reached Europe across the Mediterranean, mainly to Greece and Italy. Of these, 3,735 were missing, believed drowned.

Another notable shipwreck occurred on 3 October 2013, when a trawler packed with more than 500 people from Eritrea and Ethiopia, caught fire and capsized within sight of an uninhabited islet off the southern Italian island of Lampedusa. Local fishermen raced to the vessel’s aid and 155 people were saved but 368 died.

As the issue returns to the headlines, the European Union’s home affairs commissioner Ylva Johansson said the bloc has “a collective moral duty” to dismantle migrant smuggling networks.

“The best way to ensure the safety of migrants is to prevent these catastrophic journeys and invest in legal pathways,” she said.

Additional reporting by agencies