Hundreds crash at dangerous rail crossings that should have been fixed. Whose fault is it?

Taylor Koehn was just 21 when a BNSF locomotive smashed into the tractor he was driving over a rural Kansas railroad crossing in the summer of 2020.

A Federal Railroad Administration accident report would later say that Koehn, who died in the crash, “failed to yield” for a train traveling 69 mph at the crossing.

“I had a terribly hard time believing he had not looked because he was my careful driver,” Melanie Koehn, Taylor’s mother, told The Star recently. She learned later that some believed “he looked down the line for a long line of cars. (But) because it was only two engines, he did not see it.”

That intersection had only crossbucks — signs with a large X and the words “Railroad Crossing” — to warn drivers about oncoming passenger or freight trains. Like many crossings nationwide, especially in rural areas, it had no flashing lights. No gates. Locals would also say that vegetation often obstructed the view there.

What Melanie and Jason Koehn didn’t know at the time was that the crossing had been on a state list for safety improvements. Seven weeks earlier, the state and BNSF had just reached an agreement to install the gates and lights. But those devices wouldn’t be added until months after Taylor’s death.

The long, winding path to get projects like this approved often becomes mired in bureaucracy, leaving thousands of crossings nationwide unprotected and potentially dangerous for years, a Kansas City Star investigation found. Despite the ability of the cash-rich railroads to pay for the improvements outright, they don’t start the project until there’s a full agreement with the government, which pays for most or all of the work.

As a result, people across the country are dying at crossings that have been tagged for safety upgrades, the investigation showed.

Had those fixes been made, and active warning devices installed, many of those deaths likely could have been prevented.

“For over 100 years it has been the railroad’s legal responsibility to keep their crossings safe for the public,” said Grant Davis, a Kansas City attorney who has become nationally known for suing railroad companies, including BNSF and Union Pacific. “But now they try to push that responsibility off to others.

“Some crossings are so dangerous you only have a couple seconds between life and death if you happen to be unlucky enough to be on a collision course with a train.”

Railroads deny that they can implement safety upgrades on their own. They say they have to follow the procedures established by each state.

“Because they are traffic control devices (like traffic lights), the jurisdiction to install these at public crossings lies solely with whatever state or local authority governs that road,” said Connor Spielmaker, media relations manager for Norfolk Southern Railway. “With that said, the installation of those automatic devices does not equal automatic safety.”

He said Norfolk Southern data shows that “most at-grade crossing incidents happen at crossings with those automated devices.”

Kansas and Missouri railroad crossing fatalities

This map shows the locations of fatalities at public highway-rail crossings in Kansas and Missouri since 2017. Kansas has 5,039 public rail crossings. Of those, 57% have no lights and gates. Missouri has 3,311, about half of which have no active warning devices. Click on each red dot to see the number of fatalities at each crossing.

Safety advocates counter that it’s the deaths at unprotected crossings that can be prevented.

Railroads say they also work with local, state and federal officials to help eliminate what they view as preventable accidents on their property.

“Because trains often require a mile or more to stop and they cannot deviate from their course, safety at grade crossings is by its nature primarily the motorist’s responsibility,” said Lena Kent, BNSF Railway’s general director for public affairs. “The warning devices are there to alert motorists, not trains.”

Since a June 27 Amtrak derailment that killed four people near Mendon, Missouri — at another crossing that had been pegged for safety improvements that never happened — The Star examined transportation records for the 12 states with the most miles of public track in the country. Those states include Kansas and Missouri, as well as California and New York, several in the Midwest, Pennsylvania, Texas and Georgia.

Reporters created a database of fatalities at public highway-rail crossings in those states, looking at the number of deaths at each crossing, the vehicles involved, whether the crossing had lights and gates and if the collision occurred in a rural area.

In the past five years, Missouri alone had 12 fatalities at crossings that were on the state’s list waiting for safety upgrades — the most among the states The Star examined. In Kansas, at least three people died at intersections that had already been identified for future work but it wasn’t done until months after those tragedies.

Like most states, Kansas uses a specific blueprint when prioritizing which crossings will receive safety improvements, said Steve Hale, director of communications for the Kansas Department of Transportation.

“Our program takes a systemic approach to address the higher exposure crossings hopefully before a crash occurs,” Hale said. “KDOT’s current priority formula does not take into account whether there have been crashes at a location.”

The investigation also revealed:

▪ Rural communities or small towns are especially hard hit. In the states examined by The Star, nearly 46% of the deadly collisions occurred in those settings. That snapshot does not include California, where the vast majority of the 208 fatalities — 72% — involved pedestrians and were mostly in urban areas.

▪ Despite studies that show flashing lights and gates can significantly decrease the number of collisions, many crossings nationwide still don’t have them. In 11 of the states that The Star investigated, 90 of the 406 deadly crashes occurred at crossings that only had crossbuck signs as warnings. In Missouri, 17 of the 30 fatality crashes occurred at such crossings, leaving 22 dead.

▪ The price tag for safety projects at railroad intersections has skyrocketed in recent years, which officials say has reduced the number of crossings they can fix. In addition, not only does the government foot most of the bill for these safety improvements, it pays the railroad to do the work. Those railroads will submit invoices for everything from labor costs to meals and lodging for their own workers.

▪ The National Transportation Safety Board investigates a miniscule number of railroad accidents — only 14 of the 1,887 it should have done in 2021. The board has no enforcement authority, and when it makes safety recommendations, they often are ignored.

Still, more could be done to prevent loss and life-altering injuries at these railroad intersections, said Thomas Chapman, who has been an NTSB member for three years.

“It breaks my heart to hear about any of these tragedies,” Chapman said.

His late grandfather, a volunteer firefighter, was killed in a collision with a train at a crossing in the 1950s when returning from a call. Because of that, Chapman said, he has focused on crossing safety as “part of my portfolio at NTSB.”

“I think it’s easy sometimes to treat these tragedies in somewhat of an abstract fashion,” he said. “But I think all of us should try to remember, these are people. These are people who have loved ones and families.”

It’s difficult to get the point across, said Davis, the Kansas City attorney, that most people who are struck by trains aren’t intentionally being careless.

“The vast majority of people getting hit by these trains are just trying to get to work or trying to go to church or do whatever they’re normally doing,” Davis said. “They’re not trying to outrun the train, not out late at night drinking.

“At some crossings they have very little opportunity to see the train, and they should not get the death penalty for that.”

A fix came too late

On that late July day two years ago when Taylor Koehn was killed, his mother was resting in her central Kansas home and his dad had just gone outside to do some chores.

Neither knew about the deadly train crash that afternoon at a crossing a couple of miles away. But Melanie and Jason Koehn — members of a tight-knit Mennonite community in Harvey County — were about to learn devastating details of what happened.

“He came back in and told me our minister and the sheriff were coming down the road,” Melanie Koehn said of her husband. “And we both knew instantly.”

Their older two children — a son and daughter — were at jobs where their parents figured they were safe, so their concern went immediately to Taylor, the youngest. Drawn to farming since he was a little boy and liked anything that would “moo or wag its tail,” the 21-year-old was working somewhere in the county for his boss, a local farmer.

The sheriff told them that Taylor, who was driving a tractor and pulling a farm implement, was crossing the tracks when he was struck by an oncoming BNSF train, consisting of two locomotives.

Since 2017, there have been at least 24 highway-rail collisions with 26 fatalities at public railroad crossings in Kansas alone. Of those intersections, nine were equipped with just crossbuck signs and no lights or gates, like the one where Taylor was killed.

Transportation leaders say that installing lights and gates at intersections across the country could prevent up to 90% of the highway-rail deaths.

“They’re usually very, very catastrophic accidents,” said Nathan Karlin, a Manhattan, Kansas, attorney whose firm has specialized in train crash cases for decades. “They say it’s like a car hitting a soda can. And the heavier the train or the heavier the truck and the faster the trains are going, the more catastrophic in nature the accidents become.”

Yet the railroads and states still fail to make intersections safer, The Star found.

About half the 130,000 railroad crossings in the country are still “passive,” according to the Federal Railroad Administration. That means they are like the crossing where Taylor Koehn was killed, with no warning devices such as bells, lights or gates.

Studies have shown, Karlin and others agree, that even adding flashing lights with no gates at a crossing can reduce the frequency of collisions by up to two-thirds.

The percentages of passive crossings vary from state to state. In Minnesota, 67% of the state’s 4,300 public highway-rail crossings have no active warning devices. In Georgia, nearly 57% of the public, at-grade railroad crossings are passive. In New York, about 27% of the public railroad crossings are passive, with just crossbucks.

And in Kansas, 57% of the 5,039 public, at-grade highway-rail crossings have no active warning devices.

“It’d be nice to have cross arms (gates) at every crossing,” said George “Chip” Westfall, who has been a Harvey County commissioner for the past 16 years. “However, that is financially impossible.”

In his time as commissioner, he said, the county has seen roughly one safety improvement project at a crossing every two years.

“The local people know if they’ve got a dangerous intersection/crossing that has vegetation that is grown up or the grade of the road doesn’t match anymore, it’s been washed out or wore down,” said Westfall, who was a state trooper for 20 years.

That’s when motorists or pedestrians, he said, need to use caution and abide by a well-known mantra:

“You’ve got to live with ‘Stop, look and listen.’ If it’s not cross-arm controlled, ‘Stop, look and listen.’ ”

Right after the crash, Melanie Koehn remembers inquiring about the need for that crossing to have lights and gates. She said someone at the time told her that there hadn’t been enough crashes to warrant those warning devices.

The Star found railroad records that show Taylor’s crash was the fifth at the crossing in just under 40 years. In May 2019, a BNSF train rammed into a car at the intersection, injuring the two people inside.

The FRA accident report for that crash shows that the view of the track was obstructed by vegetation.

Melanie Koehn said she also was told that there had been a railroad spike sticking up at this crossing that farmers in the area were aware of and had even tried to remove or adjust.

“The camera on the train shows (Taylor) looking down as he was crossing because his boss said he was watching that spike,” she said. “He was watching that spike so he didn’t hit it with a tire and ruin the tire.”

Along with working for the local farmer, Taylor and his dad had a few cattle of their own, something his parents started him on when he was 13 or 14. And when they needed hay, Taylor started his “own little hay business,” too, his mom said, and would bale some for a neighbor and himself.

“He would sometimes be baling hay late at night,” Melanie Koehn said. “He was happy if he was working.”

The way the Koehns “can come through and find peace” after Taylor’s death, his mother said, is “knowing that he is in heaven.”

“God prepared him for that,” she said. “And that is God’s plan to take us all there.”

Months after Taylor’s crash, as his parents were headed to see their older son and his wife, they noticed construction underway at the crossing.

“We were quite astounded,” Melanie Koehn said. “They had told us immediately that that would not happen. … On one side you can say, ‘Well, thank goodness!’ We felt like that would be a small part to save somebody else from going through what we did.

“And the other side says, ‘Well, I wish they’d have done it six months earlier.’”

Many injured by trains and family members of those who have been killed at crossings have sued railroads for negligence or wrongful death. But not the Koehns.

“We are Mennonites,” Taylor’s mom said. “We do not sue.”

Taking it to a judge and jury

Railroads, however, do take cases to court. And they fight vigorously when they are sued.

“The railroad culture is just scorched earth,” Davis said. “They’d rather pay millions of dollars to defend these lawsuits but not dust off one penny for the widows and orphans it creates. It’s a weird culture.

“The railroads do not look at their own fault in railroad crossing incidents and always blame the driver.”

Operation Lifesaver Inc. — the nationally-recognized leader of rail safety education, which has been credited with helping reduce the number of train-vehicle collisions in the past 50 years by more than 80% — illustrates that philosophy. On its website, the nonprofit states:

“Trains have the right of way 100% of the time over emergency vehicles, cars, the police and pedestrians.”

Statements like that only further rile critics who dismiss the organization as a mouthpiece for the railroads, which they say refuse to accept any responsibility.

Accident reports — compiled by the Federal Railroad Administration from information provided by the railroads — are full of phrases like “failed to yield,” “driver inattentiveness,” “fouled the tracks” and “went around gates.”

Those reports also omit crash details, sometimes include inaccurate information such as the vehicle description or the direction it was traveling and say the view of the track was not obstructed by vegetation, trees or buildings when the satellite map of the crossing clearly shows that it often is.

Sometimes, fatalities occur because motorists get trapped or pinned in on the tracks by traffic. Other times, drivers wait for one train to pass and then start across the tracks only to be hit by a train coming from the opposite direction. And sometimes, crash experts say, the lights and gates fail to work.

When asked about fatalities at crossings nationwide and their failure to make the intersections safer themselves, the railroads point to driver responsibility.

“The vast majority of these accidents are preventable and are due to human error such as driving around gates and illegally using tracks as a shortcut,” said Kent, of BNSF.

The Federal Railroad Administration, which issues, implements and enforces railroad safety regulations, ensures that railroads use federal funds to complete projects outlined in each state’s improvement plan.

“We would expect that they would identify these crossings that are obviously problematic to be addressed,” said Karl Alexy, the FRA’s associate administrator for railroad safety and chief safety officer. “We’d look at the state action plan to see what they said they’re going to do and we can hold the states to that. That’s where our authority really sits.”

As far as requiring them to upgrade these hazardous crossings sooner? “I don’t know that we have the authority to tell them to do anything,” Alexy said.

He acknowledges that the information in the FRA accident reports comes from the railroads. But the FRA, he said, has a team that reviews those reports and if something doesn’t add up “we’ll call them out.”

Local authorities often investigate crashes at crossings but can rely on railroads for confirmation on what happened.

So unless a case goes to court and witnesses and railroad experts are called to testify, sometimes the only details known about a crash come straight from the railroad.

But more and more cases are ending up before a judge and jury.

A 2014 article in Texas Lawyer, titled “BNSF Railway: The legal department that could,” describes how that railroad had started taking a more aggressive approach to personal injury lawsuits. It said BNSF, which was purchased by American business magnate Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway in 2010, had increased the number of personal injury cases it took to trial from about 10 a year to a high of about 50 a year.

“We can say authoritatively that BNSF is trying more personal injury cases than the rest of the railroad industry combined,” said Charles Shewmake, BNSF’s vice president and general counsel at that time.

After the June crash near Mendon, BNSF and Amtrak filed one of the first lawsuits. They sued the owner of the company whose truck was involved in the crash, saying the driver “failed to yield the right of way” to the approaching train “despite the fact that it was unsafe, careless and reckless to do so...”

Nowhere in the suit, filed in U.S. District Court, does it say the railroad knew that farmers and neighbors had complained for several years about the Porche Prairie Avenue crossing. Nor does it explain that the same crossing was put on a state improvement plan for safety upgrades in 2021, but the money and project hadn’t been officially approved yet so the needed gates and lights were never installed.

Another Missouri crossing — on a county road between Warrensburg and Sedalia — was the location of a violent crash 25 years ago that left one woman with more than 20 broken bones and a traumatic brain injury.

That crossing, like the one near Mendon and the Kansas one where Taylor Koehn died, had already been identified as needing active warning devices. At the time of the 1997 crash, the only things alerting motorists about oncoming trains were crossbucks.

A four-car Amtrak train headed from Kansas City to St. Louis smashed into a car that Kimberly Alcorn was riding in. The train was traveling 65 to 70 mph when the collision occurred.

Alcorn sued Amtrak and Union Pacific, which owned the track. Officials with Union Pacific knew for nearly a year before the crash that the crossing east of Warrensburg needed lights and gates to warn drivers, court testimony showed. State officials had told the railroad that the view at the crossing was 90% obstructed by brush and terrain.

Three months before the crash, the state gave approval to the railroad to come up with a preliminary engineering plan and cost estimate for installing lights and gates, court records show. That authorization came about a month after an Amtrak train struck a truck at that same hazardous crossing, killing the 22-year-old driver.

At Alcorn’s civil trial, her attorney, Davis, told jurors that all railroads stopped paying for safety upgrades after federal and state subsidies were introduced in 1973 to help pay for the work.

The Jackson County jury awarded Alcorn $120 million in punitive damages and $40.4 million in compensatory damages.

Jurors said they wanted the hefty award for damages to force Union Pacific and other railroad companies to pay for safety improvements at crossings themselves rather than wait for the government to do it.

“It’s their railroads,” one juror told a Star reporter at the time. “It’s their tracks — they’re responsible.”

According to that story in The Star, several jurors told Davis “in unison” after the verdict that something had to be done about the railroads before others were maimed or killed at unsafe crossings.

“Today!” one juror shouted.

Union Pacific and Amtrak appealed the case, and in 2001, the Missouri Supreme Court upheld the judgment for compensatory damages but reversed the award for punitive damages. In its ruling, however, the court noted that Union Pacific could have fixed the crossing itself without waiting for government funding.

“A Union Pacific representative testified that it was possible to upgrade crossings using its own funds, without state or federal funds, and the appropriate approvals would be granted,” according to the ruling.

Missouri’s highest court went on to note: “A Union Pacific official testified that the railroad does not take any responsibility for identifying hazardous crossings and spends no money on its own for eliminating hazardous crossings. Union Pacific has never spent its own money in Missouri to upgrade a crossing to lights and gates, but waits for public funds.”

When the state determined that the crossing needed lights and gates, the court said, Union Pacific didn’t tell Amtrak engineers or do anything to inform the public.

“The railroad’s representative testified that ‘we were letting the process take care of itself.’”

Tragedies spark change

Layton Rogers, a 16-year-old Ohio teen, texted his mother after school one afternoon in May 2017. The Kenton High School sophomore had made a couple of stops and said he’d be home in about five minutes.

“And then the next thing I know,” said his mother, Laurel Rogers-Minter, “the sheriff was at the front door.”

With her 7-year-old daughter nearby, she learned that Layton’s car had been hit by a train at a crossing between Kenton and Dola, about four miles from their home. Her son, who she said was “your typical high school boy” who loved soccer, dirt bikes and video games, had not survived.

Authorities said Layton didn’t yield at the crossing and was struck by a CSX locomotive pulling two cars. The crossing had no lights or gates, just crossbucks and a yield sign.

Another teen had died in a crash there in 1993.

Nobody knows why Layton didn’t stop that day. His family thinks he might have been distracted but said he wasn’t on his phone.

“A lot of people thought it was like a full-size train,” Rogers-Minter said. “But it was only three cars. So if he did look, there was a good possibility that he might have just looked completely past it. And maybe he didn’t look at all and just thought, you know, ‘It’s a yield, I’m gonna fly over there, it’ll take me two seconds.’”

Like many mothers, Rogers-Minter said, she worried about her son when he started driving.

“Of course, I worried about accidents, but I never in a million years thought that it would be from a train,” she said. “They’re so big, and they’re so loud. And it only takes you a second to get across the tracks. What are the odds of that happening?”

Sheriee Bowman, of CSX, said the safety of employees and residents in the communities where the railroad operates is the No. 1 priority for the company.

“Our goal is to have zero incidents at our railroad crossings, so for us one crossing collision is too many,” Bowman said. “National statistics from the Federal Railroad Administration show fewer and fewer crossings collisions across the country over the last several decades.

“Our efforts to close crossings together with educating drivers on how to safely cross railroad tracks are effective, and we remain focused on that mission.”

After Layton’s death, the mother of the boy killed at the crossing 24 years earlier contacted Rogers-Minter, and the two developed a close friendship. And Layton’s mom vowed to make sure that no more lives were lost at that crossing.

“It was just a mission,” she said. “I have family that drives down that road every day, and I have family that have kids that drive down that road every day. And we have neighbors that have kids that are going to drive down that road.”

The intersection, similar to others in the nation where deadly crashes have occurred, wasn’t on any official improvement plan for safety upgrades. But many go on the project lists soon after a tragedy.

Rogers-Minter began campaigning in Ohio for lights and gates at that crossing soon after her son’s death. She was included on a team of state, county and railroad officials that went to the site two months after the crash to conduct a diagnostic review.

With the pressure from Rogers-Minter and other safety advocates, the process moved faster than most. Three weeks after the visit to the intersection, the Ohio Rail Development Commission authorized $296,000 in funding for CSX to do the work.

The cost was covered by funds from the Federal Highway Administration, and the improvements were completed in early 2019.

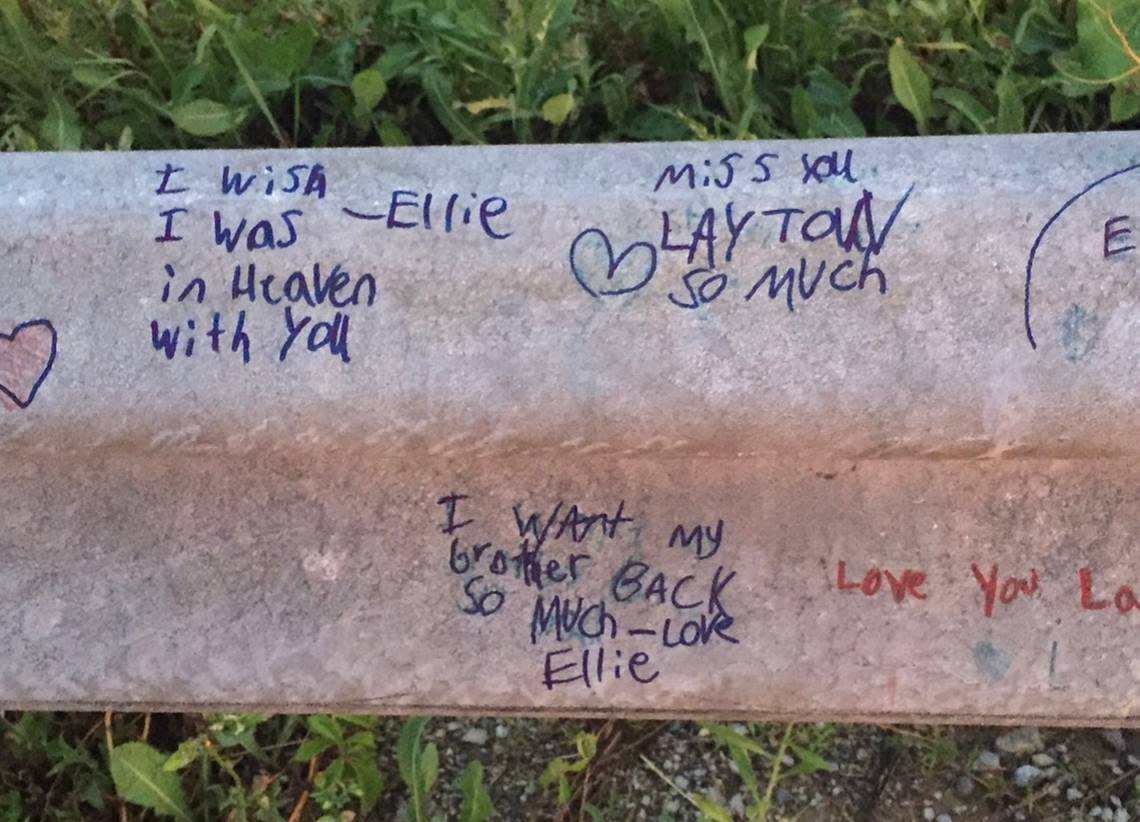

Layton’s family put up a memorial at the crash site, a sign his father made with his picture on it. There’s also a cross and colored markers so people can write messages on the guardrail.

“And his friends come out,” Rogers-Minter said. “Family and even strangers have stopped and written notes on it.”

Family members pass over the crossing almost daily and say “Good morning, Layton.”

“I tell his sister, ‘This is where your brother went to heaven,’” Rogers-Minter said.

“There’s plenty more of these crossings out there. And it’s sad that it has to come to this for something to be done.”

Lessons from Chariton County

The NTSB’s investigation into the Mendon derailment won’t be completed until sometime next year. These probes typically take from 12 to 18 months, sometimes longer.

Immediately after that crash in Chariton County, the safety board sent a 14-member team to investigate. They’ve spoken to government officials and talked to farmers and other locals and learned there were warnings about the Porche Prairie crossing that go back to early December 2019.

That’s when Mike Spencer, who farms the land near the site, told the county commission about the dangers at the crossing and the steep grade approaching it. The commission and members of the community have been trying to make it safer ever since.

According to a timeline Chariton County Commissioner Evan Emmerich gave The Star in the days after the crash, the commission spoke to someone with MoDOT railroad safety a week after first hearing from Spencer.

“They told us they were aware of the issues at the crossing,” Emmerich wrote of MoDOT in his timeline. “And it is on their plans to repair. They said they would start talking to landowners to get dirt to fix the approach.”

Fifteen months later, in March 2021, the commission met at the crossing with Spencer, a MoDOT railroad safety representative and an engineer.

“Since the gravel road and railroad intersect at an angle, it can make it difficult to see,” according to Emmerich’s notes. “The crossing is used by a lot of farm equipment which would make it especially difficult to navigate.

“MoDOT still has the crossing on their list to repair but no timeline was given to us.”

Nearly six months after the crash, the crossing remains closed, with approaches on both sides barricaded to keep motorists out.

MoDOT told The Star last month that “no final decision has been made” on the Mendon location.

Chariton County is in the process of hiring a consultant to complete a study of railroad crossings in the county including this one, said Linda Wilson Horn, a MoDOT spokeswoman.

“The study will develop a master plan for what crossings should be improved,” Wilson Horn said, “what should be closed and what other roadway improvements might be needed to accommodate any closures.”

Missouri could possibly have addressed that crossing sooner — and perhaps even completed more projects across the state — had officials known about a change in how the government pays for such upgrades, The Star found.

Seemingly unbeknownst to MoDOT, the federal government has recently been funding up to 100% of the costs for safety upgrade projects, NTSB officials told The Star. States including Iowa and Ohio said that’s what they were receiving.

But in Missouri, the projects are funded with about 90% coming from the federal government and 10% from the state, according to a 2022 MoDOT grade crossing plan.

“State officials were unaware that they could get funds without having to put up matching funds,” said Robert Hall, director of the NTSB’s Office of Railroad, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Investigations. “That’s kind of a significant thing. … They had indicated to us that the matching fund was a hurdle to getting certain projects done.”

Hall said that “Missouri is the first one that we’ve come across” that didn’t know it could get 100% federal funding for the crossing upgrades.

Chapman told The Star that the issue likely would be part of the recommendations the NTSB makes when the board concludes its investigation.

“I’m going to go out a little bit on a limb here, because the investigation is still ongoing, but it sounds like one of the lessons that will come from that investigation has to do with the availability of funding,” Chapman said.

Wilson Horn, of MoDOT, said her agency is aware that the federal funding is now available to states at 100%. However, she said, “The match is not the hurdle, it’s the amount of available funds that’s the hurdle.”

The Porche Prairie Avenue crossing isn’t the only deadly intersection in Chariton County that’s in need of attention.

About 25 miles southeast of Mendon sits the “Cal Hubbard crossing,” where two people have been killed since 2017 and a third was injured in 2014.

In April 2017, 36-year-old William Thomson, of Salisbury, died when his tractor pulling a farm implement was struck by a Norfolk Southern freight train. A Missouri Highway Patrol crash report said Thomson failed to yield to the train.

Nearly four years later, in February 2021, Leland Linneman, 60, also of Salisbury, was driving his pickup over the crossing when it was struck by a Norfolk Southern freight train. Linneman died two days later.

At the time of Linneman’s death, that crossing had already been slated for improvements, but they hadn’t been made yet.

Wilson Horn said MoDOT authorized the final design and installation of lights and gates on May 31, nearly a month before the Mendon crash.

Spielmaker, of Norfolk Southern, said the work recently began and the project is expected to be completed in seven weeks.

A cross has been placed at that intersection with the names WILL and LELAND surrounded by hearts, along with the phrases “In Loving Memory” and “Carrying Your Love With Me.”

It serves as a reminder for passing motorists of what happened here, at one Chariton County crossing, in the past five years.

And the black barricades blocking another crossing just 25 miles across the county, near Mendon, serve as another.