Humility offers us an exit ramp off the road to perdition

One theme I return to again and again here is the necessity of humility.

As I’ve aged and presumably gained life experience, I’ve come to believe hubris is a besetting, endemic sin afflicting the human race. It’s the source of most of our problems—from broken marriages to bad politics to our wounded natural environment.

Look at nearly every modern dysfunction large or small, and at its crux is somebody, or a lot of somebodies, convinced they’re superior and have all the right answers. Or perhaps secretly they know they aren’t superior and don’t have the answers, but pride and pride’s twin, the fear of losing face, keeps them from being honest.

Thus has it always been, I suppose, which is why I keep writing about this subject—because we need to recognize this spiritual sickness again and again, daily, hourly.

I don’t claim to be a scholar, but in my largely untutored reading of the Bible I see pride as the culprit in the Genesis story of Adam and Eve. It’s the original sin, if you will.

Want to understand how the first couple fell from Paradise and doomed the rest of us to perdition? The answer is pride.

The temptation the serpent puts before them is this: if you eat from this tree, you will be as powerful and wise as God.

And so, of course, they eat the fruit. Boom, all hell breaks loose.

The metaphor is clear … to me, anyway.

This story isn’t about eating a forbidden apple. (There isn’t even an apple in the story.) The story’s point is that Adam and Eve have it made. They live in Eden. God loves them. He provides for them. He gives them dominion over all creation.

Yet it’s not enough, because someone else is wiser, exercising more authority than they have. The one who’s greater than Adam and Eve is God. So they want what God has. They don’t want to follow God. They want to be God.

Some argue that the sin in the Garden is greed. Adam and Eve want ever more, they say.

Yes, but underneath the greed lies pride. They can’t humble themselves and accept just being second-best, even to the Lord God Almighty. They’ve got to be first, all the time.

The result, then as now, is disaster.

Our perpetual striving for supremacy certainly has an upside, which is what makes it tempting. Because of pride and competition we end up with better ball teams, better cars, better science gadgets, better TV dramas. We live to beat our competitors and brag about our achievements.

The downside, however, is cataclysmic. It’s why we end up with broken marriages, dysfunctional churches, ruthless corporations and world wars.

In our race to be the best and accrue honors, we dismiss, abandon or attack those we perceive as our inferiors.

And when we fail to win, as the great majority of us will eventually, we crash into despair, turn to drugs or hang ourselves. If only one person can win, everybody else is a loser. What a pitiable way to live.

In Christianity, we’re taught the only exit off this hamster wheel is to embrace humility. To become spiritually healthy, we must surrender our ridiculous pride.

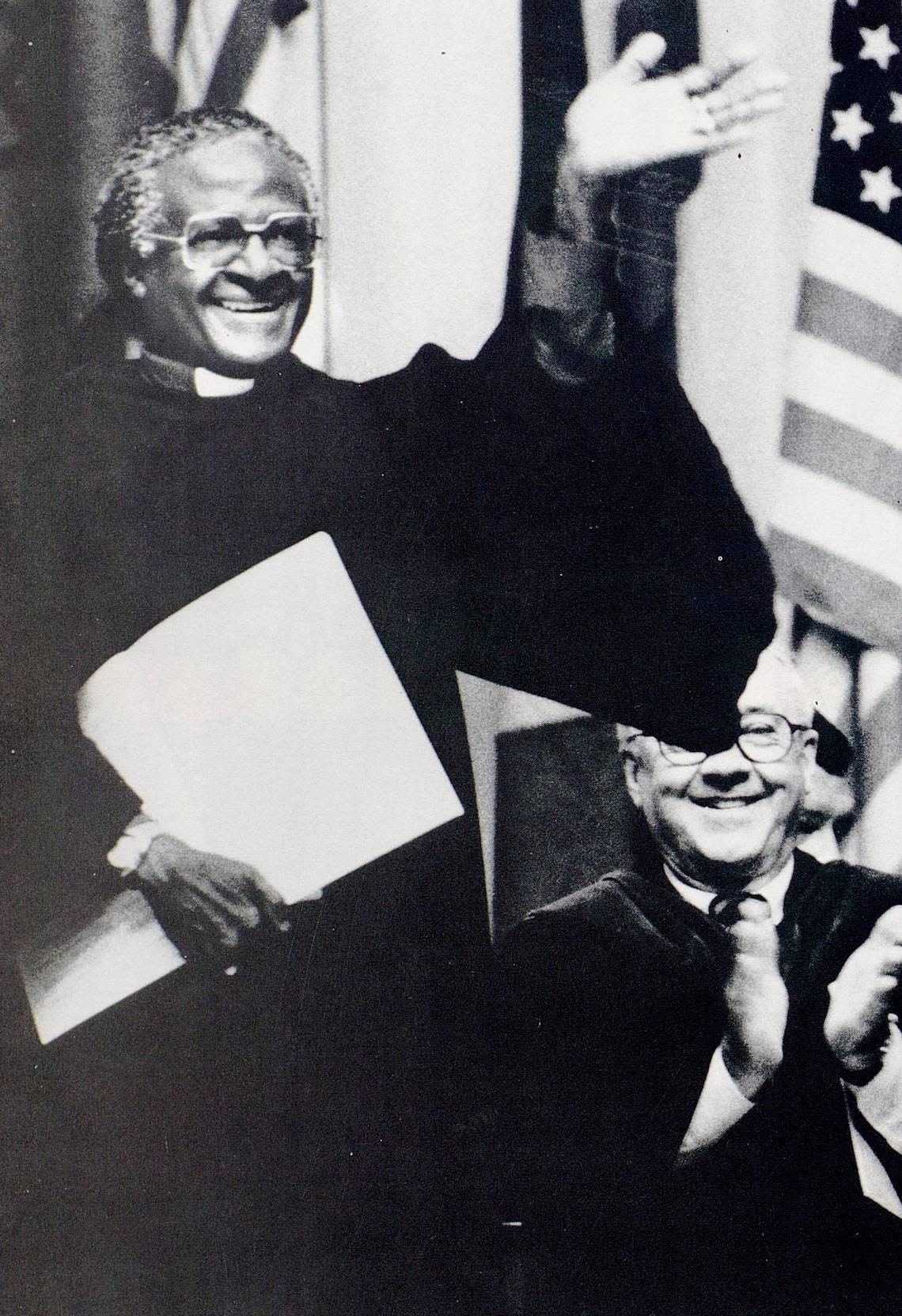

Among the exemplars of this virtue was the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who learned humility while enduring the indignities of South African apartheid.

In a book on forgiveness co-written with his daughter, Mpho A. Tutu, the archbishop discussed how humility enabled him to forgive his oppressors.

“We want to divide the good from the bad, the saints from the sinners, but we cannot,” the Tutus wrote (as quoted by my spiritual guru, Richard Rohr). “All of us share the core qualities of our human nature, and so sometimes we are generous and sometimes selfish. Sometimes we are thoughtful and other times thoughtless, sometimes we are kind and sometimes cruel. This is not a belief. This is a fact.”

Ultimately, such a clear-eyed lack of self-righteousness urges us toward reconciliation with God, ourselves and our rivals. We acknowledge our own imperfections before we condemn others’. We quit seeing ourselves as uniquely holy.

“We are, every one of us, so very flawed and so very fragile,” the archbishop said. “I know that, were I born a member of the white ruling class at that time in South Africa’s past, I might easily have treated someone with the same dismissive disdain with which I was treated. I know, given the same pressures and circumstances, I am capable of the same monstrous acts as any other human on this achingly beautiful planet. It is this knowledge of my own frailty that helps me find my compassion, my empathy, my similarity, and my forgiveness for the frailty and cruelty of others.”

Imagine how our families might prosper, how our workplaces might improve, what shining examples our churches might become, if we approached all our problems through such humble eyes rather than through delusions of our own grandeur.

Paul Prather is pastor of Bethesda Church near Mount Sterling. You can email him at pratpd@yahoo.com.