House passes ‘decolonization bill’ to allow Puerto Rico to decide its political future

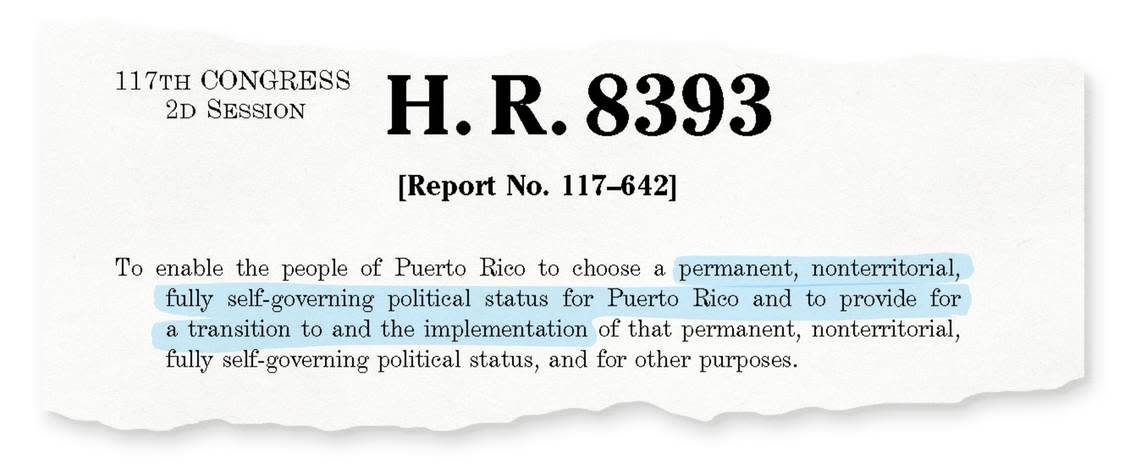

The House of Representatives passed a bill Thursday afternoon that would allow residents of Puerto Rico to choose from three status options in a binding special election and end its 70-year-old current territorial status.

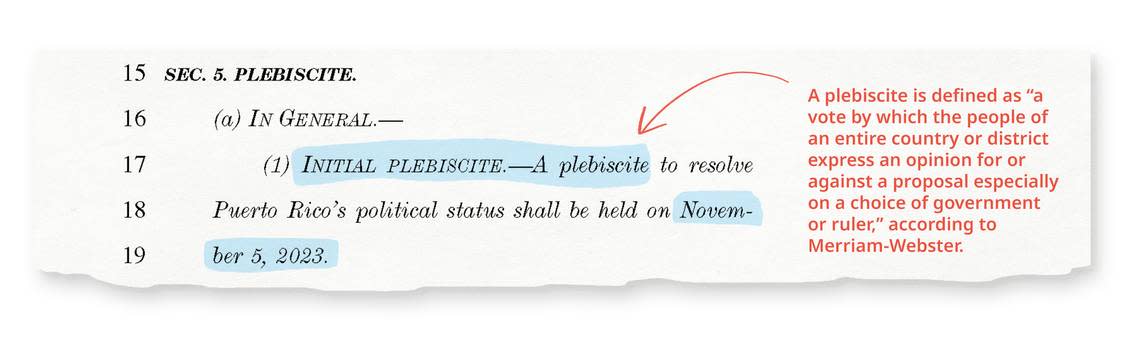

The bipartisan bill, known as the Puerto Rico Status Act, would establish a plebiscite to be held in November 2023 in which eligible voters would choose from three options: statehood, independence, or sovereignty in free association with the United States.

There were 233 votes in favor and 191 votes against the bill. The votes occurred mostly along party lines, with Democrats overwhelmingly voting in favor of the measure. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democrat from New York with roots in Puerto Rico, was the temporary speaker during the vote.

Democratic New York Rep. Nydia Velázquez, a bill sponsor and the first Puerto Rican woman elected to Congress, told the Miami Herald that it was “really, truly a historic day” and the bill “set the record as to what are the fundamental principles that should be included in a decolonization bill.”

“We have accomplished what many thought would never happen,” she said.

What the bill would do

If the bill becomes law, it would be the first time Congress would have to accept the outcome of a referendum on the island to determine the American territory’s political future. The plebiscite would not include the island’s current political system as an option, bringing the decades-long current commonwealth status to an end.

If voters chose statehood, the island would join the U.S. as the 51st state; if they opted for independence, Puerto Rico would become a sovereign state with authority over its laws, economy and citizenship. Under the free association option, the island would be an independent nation with foreign and economic agreements with the U.S., as well as American citizenship for its residents under the first agreement.

The bill also provides funding for a bilingual nonpartisan educational campaign to explain the three options to eligible voters in Puerto Rico. Any of the status options would require a majority vote to win. If this didn’t happen, there would be a March 2024 runoff election where the two top options would face off.

Democratic Arizona Rep. Raul Grijalva, chairman of the House Committee on Natural Resources that oversees issues about Puerto Rico and other territories, along with Velázquez, Republican Puerto Rico Resident Commissioner Jenniffer González Colón, Democratic Florida Rep. Darren Soto and House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, D-Md., are the main sponsors of the bill.

To become law, the bill still needs to be passed in the Senate and be signed by President Joe Biden. The Executive Office of the President issued a statement in support of the bill on Wednesday.

“The President calls on Congress to act swiftly to put the future of Puerto Rico’s political status in the hands of Puerto Ricans, where it belongs,” it reads.

Velázquez told the Miami Herald that she would be reaching out to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer to request a meeting and discuss the bill.

At a press conference after the bill’s passage on Wednesday, the island’s resident commissioner acknowledged that it was unlikely that the bill would pass in the Senate before the end of this congressional session on Jan. 3, in which case the bill will die.

“However, I believe in miracles,” González Colón said.

Leo Aldridge, a Puerto Rican lawyer and political analyst, described the bill’s passage as significant from a “symbolic and historical perspective” and as an “achievement towards decolonization.”

“It is the first time that the federal House of Representatives states that Puerto Rico should be governed in a system that is not the territory,” he said.

However, Aldridge believes that the bill will face an uphill battle in the Senate, and that it wouldn’t have the 60 votes required to overcome a filibuster.

“This has no real chance of becoming law because the Senate is not going to consider it,” he said.

Over a century of U.S. rule

The United States invaded Puerto Rico in 1898 and established military rule after triumphing over Spain in the Spanish-American War. Puerto Ricans later became U.S. citizens in 1917 under the Jones-Shafroth Act, and Congress first allowed the island to elect its first governor in 1948. Since 1952, the island has been under its current political status, known as Estado Libre Asociado, or the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, when eligible voters on the island voted for this form of governance through a constitutional referendum.

Under the commonwealth, Puerto Rico chooses its own governor, two-chamber legislature and municipal mayors, but Puerto Ricans on the island cannot vote in the general U.S. presidential elections. Its residents also don’t pay federal income tax. The island has a resident commissioner that represents 3.2 million residents in Congress. The commissioner can participate in committees and introduce legislation, but has no vote on the House floor.

Puerto Rico’s political status is the subject of fierce debate and its local political parties have historically been organized around the issue. Backers of the current status, which has lost the favor it once commanded, say that the status allows the benefits of a close political and economic relationship with the United States while allowing the island to maintain sovereignty and culture.

Those who oppose it, which include people who support a permanent relationship with the U.S. through statehood or the island becoming an independent country, argue that the current political status is a vestige of colonialism and blame the commonwealth for the island’s woes. Puerto Rico has lost hundreds of thousands of residents in the last decade, weathered a severe economic crisis that led to the government’s bankruptcy, and struggled through the aftermath of hurricanes and earthquakes.

The most recent political status referendum was held in November 2020, with about 55% of the island’s 2.3 million eligible voters participating. It asked: “Should Puerto Rico be admitted immediately into the Union as a State?” with 52.52% of voters saying yes, and 47.48% voting against. It’s the most recent of six status referendums that have taken place on the island since the late 1960s. However, these plebiscites were non-binding, and Congress was not required to take action based on their results.

Puerto Rico’s fate in Congress

In Congress, supporters of the bill have emphasized that it is a way to allow Puerto Ricans to choose their own political future while moving away from territorial status. Backers of the bill include representatives with roots in Puerto Rico from both parties, including Velázquez, Ocasio-Cortez, Soto and González Colón.

Meanwhile, detractors say that the bill was not drafted or brought to a vote in a transparent way and that the options presented do not fully discuss the consequences each could have on the island. Some critics have also taken issue with the bill’s stipulations that if Puerto Rico were to become independent, it would have to maintain democratic principles such as due process, freedom of speech and press, and equal protection under the law. While they acknowledged that they agree with these ideas, they question why Congress should determine what the island would include in its own constitution if it were a free nation.

Sponsors of the bill gathered to celebrate and discuss the bill’s passage at a press conference following the vote on Wednesday afternoon. Puerto Rico Gov. Pedro Pierluisi, who traveled to Washington, D.C., from San Juan to witness the vote, was in attendance.

Rep. Soto, a Democrat from Kissimmee, described the bill’s passage as a “miracle” and said that he favored statehood for the island. Meanwhile, Miami Republican Rep. Maria Elvira Salazar, who described herself as a “Cubarican,” said that Puerto Rico had opened doors to her family who had fled Cuba after Fidel Castro took over, and that this was her way of paying back Puerto Ricans after they welcomed her family.

“Moments like this have not been seen in Congress in the last two years, Republicans and Democrats working together on a bill,” she said in Spanish.

The bill has six sponsors from Florida, a stronghold of the Puerto Rican population in the mainland United States. However, not all Florida legislators supported the measure.

Republican Rep. Mario Diaz Balart issued a statement following the passage of the bill saying that Democratic leadership in the House had acted in haste and the measure “lacked the requisite debate and bicameral, bipartisan input and support to become law.”

Both Pierluisi and Soto called on Florida Sens. Rick Scott and Marco Rubio to take the lead on getting Republican support of the bill in the Senate.

When asked if Sen. Scott would support the bill, his congressional office said that “ultimately, the future of this bill lies with Senate leadership.”

“Senator Scott will continue to fight for our fellow Americans in Puerto Rico to make sure they are treated fairly,” said Sen. Scott’s spokeswoman Rosa V. Perez.

Sen. Rubio’s office didn’t immediately respond to the Herald’s request for comment.

“It’s a great day for Puerto Rico,” Pierluisi said. “I know that there will be again Republican members in the Senate who will join their Democratic colleagues to do the right thing, which is to allow the people of Puerto Rico to choose among non-territorial, non-colonial options and then commit Congress to implementing the winning option.”